A visit to an exhibition of Beauty in the Everyday: Dutch & Flemish Masters at Auckland Castle in the Trevor Gallery in The Bishop’s Palace, Bishop Auckland, County Durham. This is an account of a visit on the afternoon of 17th September 2021. Is there a relationship between Protestant Ethics and Commodity Capitalism in these Paintings?

The Trevor Gallery is an intimate suite of rooms and at the moment hosts an exhibition of paintings from (mainly) The Bowes Museum but also Woburn Abbey and various unnamed private collections also. The information board in the lobby of the gallery describes its contents as paintings that: “… originate from the seventeenth century, a period which saw the emergence of a new Dutch Republic and an upsurge in the production of art”. But the relationship between these two factors may be everything, for the Dutch Republic expressed the aspirations of a new class of rulers whose power was based on capital and its investment and the ownership of commodities that represented the wealth flowing from that source, particularly the solid form of goods and things. This is not to say that art belonged only to a monied class. One feature of this exhibition is that the interiors of modest lower middle-class homes (farmers for instance in the work of David Teniers the Younger (1610- 1690) are those in which we see art – in the affordable form of prints rather than these oil originals – on display more often than not.

Art was no longer the preserve of an institution like the Church but was instead be in private hands , but the information board here too shows that some religious, or at least versions of an ethical life, content was still to be a preserve of this art. We might see just ‘scenes from everyday life’ but should be alert, we are told to ‘more … than meets the eye’: ‘deeper, moral meaning, which reflected the climate of religious and political upheaval’. This kind of discourse is more slippery than we might think since the relationship between the ethics of everyday life and both religious and political ‘upheaval’ is necessarily complex. For instance the phrasing leaves open any possible association or relationship between what was happening in political and religious life. But one thing is clear. One mediating factor is a common interest in the meaning of a healthy economy as the outcome of hard work in the processes of production and distribution in commodities like the need for renewable food sources and goods that clothe and / or decorate the person. Within this economy are also commodities whose availability are not immediately to be equated with well-being such as tobacco and alcohol but also perhaps, for a different class, addictive items like the objects of conspicuous but not reproductive wealth – gold and jewels, but perhaps too original art, for instance.

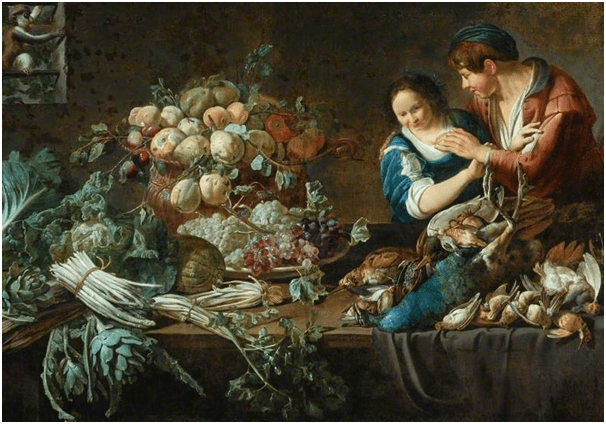

It is useful that the exhibition begins with a clear application of moral meanings whose resonance throughout the whole painting remains less available than readable with the right frame of mind in the viewer. This is a painting by Adriaen van Utrecht (1599 – 1652) from 1631. The ambiguity facing a viewer deciding on what is a ‘moral meaning’ and the representation of cold fact (if such phenomena actually exist which I doubt) is already present in its title Still Life with Lovers (see below).

The painting is well interpreted for us in the information board as an extended allegory of the ethical meanings seen in the regulation of secular love. Yet the lovers take up a lesser portion of the painting than do the details of the still life (the Dutch word contains the same idea as the English since stilleven is a composite of the words of still and life) through which everyday domestic ‘beauty’ is captured. The key is that the items do not move, although the possibility that this is because they are dead (much clearer in French equivalent art form named ‘nature morte’) is also there.

The gallery information reads the sexual morality implicit in the picture. Ominously this says, blaming the victim of rape for any potential rape in doing so unfortunately, that the female in the painting is allowing the male to go too far in his attentions, although it is not immediately clear that this is the case since she is pushing the man’s intrusive hand away from her breast. Moreover the woman is painted in a position of retreat signified by her lower lateral position and depth in the perspective of the painting as being visually dominated by the man here. However, the commentary is helpful in pointing out that the depiction of dead birds under the intrusive act is significant, since ‘vogel’ (the Dutch for bird) pairs with term ‘voegelen’ which in slang Dutch of the time is associated with sexual activity. The point to the caged monkey at the viewer’s left and the possibility that that meaning is involved in the visible decay of the fruits on display, since, I suppose: ‘You will know them by their fruits. Do men gather grapes from thornbushes or figs from thistles?’[1]

But we might go further in our moral analysis surely. We pluck living forms, whether by trapping birds as the man has done or taking fruit and vegetables from that which enables their life in order to make them commodities for human use. A Still life or ‘nature morte’ then is about death that comes about from human intervention and/or labour, as Ruskin analysed the process of work in Unto This Last; labour literally costs the expended life of human beings. Hence the presence of death in this painting may tie very closely to an ethical statement about commodity capitalism. Production, of commodities; especially to the excess required by expanding and growing capitalist economy exploiting economies of scale is already potentially immoral. It is not just that that excess is unequally distributed but that it anyway fuels the love of things alone at the heart of the system. The spots of decay on the fruit, the dead attitude of the birds and the dying leaves on the edible vegetables may all point to a moral. Choose your meaning: is it directed at the class issues – the lady, sublimely dressed is ‘allowing’ a working and younger boy to desire her as if she were a commodity (taking the line of the commentary) or the painting generalises the morality to make a point about the basis of the new and revolutionary power of the bourgeoisie based in capital. I prefer the latter obviously.

We need to take these lesions into the next display area, a passageway showing domestic stilleven art. I was not aware before this exhibition that such art had sub-genres, of which paintings of dead fish were one and those of breakfast goods, known as ontbijites, another but I do now.

Two paintings by Alexander Adriaenssen (1587 – 16661) hang here. Here is my favourite, a fish painting since it reminds me of both Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin and John Bellany. The labour of killing and butchery of dead meats is evident here in the cuts on show, into and through the skin of the fish, the livid pinks showing beautifully against ochre backgrounds.

Fish eyes are always a keen means of distinguishing motifs of what lives against what is dead, especially those uneven ones on the plaice (or is it sole?).. All human activity appears here only as an effect of killing and cutting. Are we right to moralise on this. Is there a point made in the painting relating to showing a catch of fish in excess of what is immediately edible? Who is to know? Otherwise, other paintings here can’t support this as an aim – they glory in the human interior and objects of human use without needing to show persons. Moreover, since these persons would be servants, it may be that these paintings glory in the wealth of their owners (and not users) by this omission of exploited often female labour. Such is the empty Kitchen Interior of 1650 and, by an unknown artist, the rather marvellous An Earthenware Pot, a Cast Iron Frying Pan and a Cooking pot, with a Basket and Cloth. The utensils in the latter seemed to be tipped in such a way that display ideally, perhaps another sign of the need to ban signs of overt labour so that we enjoy the beauty of the arrangement of commodities in their own combined right. They are after all a sign of a wealthy kitchen needing to prepare for people with food to spare (for themselves).

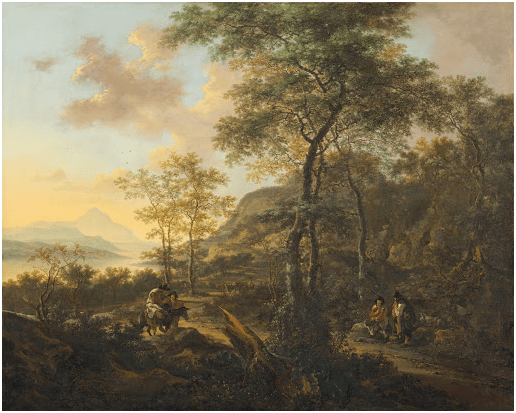

However paintings are themselves commodities. They are one of the best ways (slide-shows being impossible) for well-off people to show their wealth by their taste in travel, especially amongst the poorer people of other countries. We move to such an example now – a huge landscape by, it is though a follower of Jan Both (1615-1652) of the Italian Campagna, replete with a road to a distant city and rather impoverished travellers (possibly gypsies which were favoured in baroque art): An Italianate landscape with Travellers on a Path, Trees and a Waterfall on the Right, Mountains in the Distance (some year after 1641). Although a wonderful painting I could not find an image of it but the search was instructive since clearly Both excelled in paintings of rural paths containing travellers between cities. Here’s an example:

However the exhibition has not finished with the stilleven form yet, although barely as recognisable in this much higher class and brilliantly ‘finished’ paintings by Gillis Gillsz de Berck (1600 – 1669). For here the desire of goods, ownership and the ability to command a global market shine in ways that have completely evacuated any sign of labour – hence the tasteful ‘finish’ of the painting. The best example of this is a stilleven from a flower genre on show A Basket of Flowers with Seashells (1642)

Such paintings may occasion only a glance but it is still worth noting the attempt to capture a just living natural object and a dragonfly symbolising, we are told on the boards ‘a symbol of the beauty of life’. The commentary also helps us to see why this painting is so important to the new extremely wealthy merchant class of Amsterdam, a place René Descartes was able to say thereof: ‘what place on earth could one choose where all the commodities and curiosities one could wish for were as easy to find as this one’. I italicise part of this quotation, available in exhibition information, in order to show that the global desires of the bourgeois individual is what all commodities of value represent.

Further information picks out the significance of tulips in the painting, since these were a Turkish import to the Flemish coast only in the sixteenth century. Moreover the varied seashells here necessarily tell the story of many cultures and places of travel and economic exploitation being imports that only the scope of the Dutch East India Company could satisfy. This then is an art of excess wealth. If the moral occasion of the scene is less than previously then this is because the owners of such art could afford not to be reminded that their wealth had a cost, often to other exploited peoples than themselves.

Portraits too are commodities and in themselves display the commodities that colour everyday life for the rich in the form of fine clothing and decorative jewellery. In this room we need to wait to see the best of this in the two fine paintings (from a private collection and therefore difficult to otherwise see) by the workshop of Rembrandt van Rijn. Before we see these see a great painting by an admittedly lesser artist, Jan Albertz. Rotius (1642 – 1666), called A Portrait of A lady in a Fur-Trimmed Dress Holding a Pair of White Gloves (1660-66).

A lot of the art of the painting is merely reproducing the fine art of the clothing here with sumptuous reds and gold framing placed together with a sumptuously rich fruit bowl, containing grapes Zeuxis himself might have painted, and thus representing the finesse of fine art. The lay is clothed with gold and is bejewelled by rings, earrings and cuff decorations featuring both gold and pearls. If the latter might enhance the morality of this rich lady, her scarlet under-dress does not; although it is difficult to suggest that the painter is referring to the Scarlet Lady here (I am sure he is not). But black and white contrasts never stand alone and this lady needs to display more than her moral rigour, she needs to show that she is both wealthy and powerful. If fine white lace is only costly in the lives of female workers, her ermine has cost animals their lives.

When you compare this painting to the Rembrandt facing it in this room, Portrait of a Lady with Fan (1643) the richer more complex painting is even harder to moralise, as great art often is, whatever our knowledge of iconography. I cannot find a reproduction of this wonderful painting but the impastos which create the effects of realistic solidity at distance seems moral when it is of the thickness and density of the neck clasp holding a pearl in her necklace. It looks heavy. It looks g(u)ilty. There are fewer attempts to contextualise her in any specified interior and the light source is difficult to describe and seems an effect of artifice and theatre.

Here seems a good place to look at the other Rembrandt here, again of 1643, the Portrait of a Man with a Hawk (see below).

This reproductions lacks the chiaroscuro effects of the original that create shadows of uncertainty in the painting however. However it enhances the recreation of young flesh in good light contrasted with dark clothing and the even darker associations of the hawk, wearing a blind, on the man’s cuff. This young man’s eyes do not attract the gaze of the viewer as the one of the Lady does, looking somewhat beyond us, on the lookout for fodder much as the hawk will when unblended. A Large gold purse clasp dominates our vision and breaks the richness of the folds of rich silk in the lightly voluminous clothing. This gold is dense, impasto created. To what does the finger point since the pointing finger is unnecessary to support the bird. It increases the sense of a man weighed down with riches.

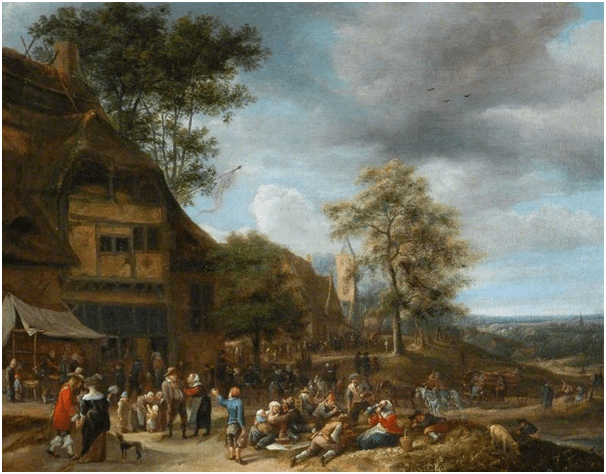

I spent very little time with Jan Steen’s (1625 – 1679) Twelfth Night in this room, but its themes of the coarsening effects of leisure, money on commodities on people of a class unable to support it with grace here very much dominate the paintings of the next room, especially Steen’s painting Villagers Merrymaking Outside an Inn (1657).

This is a tremendously powerful painting but riddled, in my view as its Bosch influences are not, with class prejudice specific to the rich nation that was the seventeenth century Dutch Republic. Of course the villagers are merely eating, drinking and smoking but these commodities are themselves not only morally of concern in excess but also coarsening. The ‘lovemaking’ of the peasant villagers is clearly meant to be contrasted with the genteel manner of the bourgeois courting couple who observe this scene for us and give it contrasts that are behavioural but also ethical. The dominance of this huge inn is deliberately contrasted with distant steeples of the Dutch church. There is contrast then of the messages of peasant merrymaking and a religion validated by a Protestant State. It is not for nothing that there is a chain of being across the bottom of the picture’s surface frame from well-clothed bourgeois to boozy coarse villagers and ending with a pig on the viewer’s right.

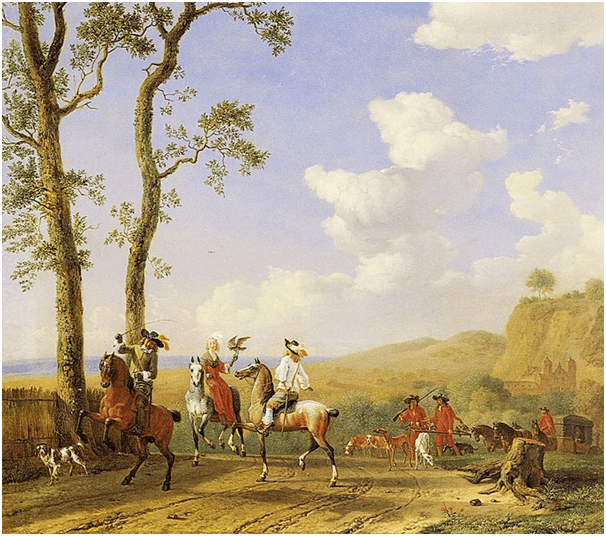

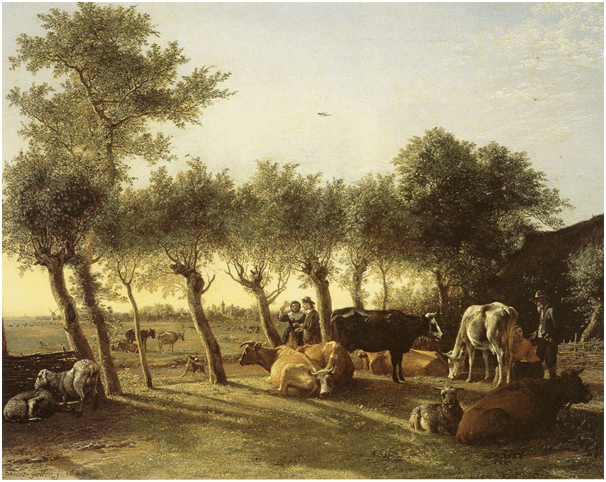

Of course Steen is a social satirist and the take of someone less threatened by class difference is clear if we contrast in this room (see both below) Paulus Potter’s (1625-1654) paintings The Hunting Party and A Farm Near the Hague. Both revel in idyllic rustic landscapes although the former emphasises the ownership and control of natural life by aristocratic life whilst the latter merges the peasants into the lull of an evening pastoral. In both cases and in the contrast, all is harmony – it is I’d say obviously ideologically so and the peasant picture in particular forms a wonderful contrast with Millet and, more so, Van Gogh on this subject where poverty and danger predominate.

More like Steen is the work in this room by David Teniers the Younger (1610-90) with his intense and often ugly farmers, or Boers but I could not find a reproduction of Interior of a tavern with Boers (1630) which shows this group contrasted with a wasted and wasteful group in a back room who had drunk and smoked, as the Boers also do, but to excess. One I did find a reproduction of is more complex. It is An interior of Figures saying Grace Before a Meal (1636 – see below).

Apart from the young woman this group is dour, especially the very ugly young children but that this farming family is in grace I have no doubt. The truest display of this is the half-unnoticed poor neighbour who is being served a beverage in the back kitchen by a maid. This act of charity is an outward and visible sign of achieved grace not just the grace that unites a family meal. We are meant to see that the family themselves do not display their charity, since grace for Calvinists does not depend on good works. It’s a wonderful painting but I can’t say I like it. Of interest is that the house sports a print showing that art was more distributed in seventeenth century because of the printing presses that made art affordable than that of original oils with their high prices that characterise other paintings here.

It is a wonderful exhibition and only there till October 3rd so needs seeing now

All the best

Steve

[1] Matthew 7: 16

One thought on “A visit to an exhibition of ‘Beauty in the Everyday’ of Dutch & Flemish Art in the Trevor Gallery in The Bishop’s Palace, Bishop Auckland, County Durham. This is an account of a visit on the afternoon of 17th September 2021.”