‘What had been like since the end of the war, physically located in a world that was shorn of the people she loved and unable therefore to participate in it, her mode of existence more akin to that of ghosts than humans, even if she’d existed in a body that possessed weight and could move physically through space, even if she remained capable of love and pain, laughter and generosity, even if the life inside her had been undeniable to anyone who saw her’.[1] Tamil identity in Sri Lanka after the civil war and the ghostly but epic life of a nation that never existed in the modern world: being a reflection on the philosophy of epic underlying Anuk Arudpragasam A Passage North London, Granta Books.

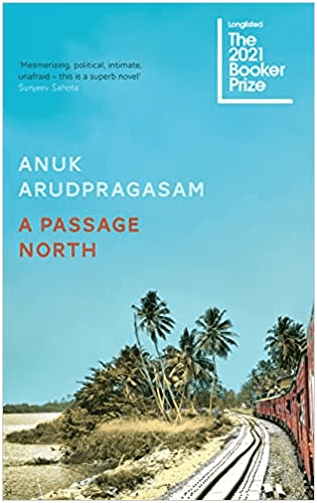

Anyone as ignorant of the history of the claims of the Tamil nationalists of what is now Southern India and northern Sri Lanka as me deserves the sense that they must be missing so much of the richness of reference of this very great novel, which presents a philosopher’s take on the fate of a failed project towards nationhood. It is philosophical rather than political because it tries to answer questions about how nationhood is present in the body of those who fought for it or even desired it as a means of understanding themselves. And it may be that such a nation cannot claim evidence for its own basis even in the aspirations of a certain demographic group. Is this the implication, for instance of a note attached to the relevant Wikipedia article, threatening the article writers to seek more documentary evidence to support their claims about the existence, import and interpretations of the phenomenon the article names as Tamil nationalism. Of aspiration, art is an index and the picture attached to this article shows a basis in conceptual visual art, as seen below. It burns coldly but clearly that message

The art of Sri Lankan Tamil novelists known to the UK probably is represented best by Sinhalese writers like Gunesekera whose early novels, at least, were nevertheless seared by the pain of the divisions and tragedies that accompanied the cruel conduct of the Sri Lankan Civil War in the North. I once used to read Romesh Gunesekera for insight but though painful to read and fringed with the tragic notions of a lost multiplicity in the possibilities of national identity, they lack the directness of a committed Tamil writer such as Anuk Arudpragasam. The former’s later novels are told in the manner of the post-colonial literature of which Forster provided a model. They feel safe and balanced compared to the wonderful The Story of a Brief Marriage published by Anuk Arudpragasam in 2016. The latter is the kind of art equated to fable and the great legends of a nation, like the stories of Greek tragedy were to Classical Athens perhaps, where the events become iconic and have meaning beyond the personal despite the careful bounding of them in the lives of a few individuals and the significance on their feelings for each other.

It is likely that A Passage North will contain much that passes a reader like myself by, since it takes on every aspect of Tamil nationhood, even if it locates it finally in the burn of embodied desire and longing for impossible completion rather than in the various branches of Tamil culture it examines- often in huge detail, such as in ancient Tamil language and literature, the specificities of Buddhism in Tamil nationhood and its relation to the fable of Siddhartha, or the lives of its revolutionaries, political martyrs and lost leaders. All of the only emerge in this novel through the consciousness of them of Krishan, the main male character and bind his and her personal lives with not only the political (we are used to that in the global West and North) but something less graspable and resident below conscious understanding of discursive reason. For instance, his desire for impossible union with a bisexual lover, Anjum , who is committed any way to her political community rather than any domestic aspiration he might offer her expresses itself through the Sivapurānam with its:

Slowly building, incantatory rhythm …, written in a Tamil from several hundred years before that he could hardly understand but which, he knew, was about the pain of being embodied … while all the time yearning to give up earthly life, to be shorn of attachment and the weight of the body and joined to the feet of Siva.[2]

We will contact that unearthly fulfilment of an identity lost to earthly possibilities throughout the novel. In different registers we hear of it also in fables of Siddhartha, as I have already suggested that Krishan comes to realise (in Delhi) a Buddhism that is a ‘religion of emancipation’ known to ‘Tamil Buddhists in the south of India and even in northeast Sri Lanka’, unlike the Buddhism of the entitled Sinhalese of the capital city Colombo.[3] The yearning for freedom from the earthly herein takes on a socio-political edge as a feeling he imagines in Rani, his mother’s servant that resulted from the trauma and loss of the Civil War for all Tamils – even privileged ones like himself.[4]

Likewise people dubbed terrorists such as the Black Tiger military suicide trainee, Dharsika, whose story Krishan and Anjum listened to on TV and set at a lake which prompts memory of that viewing as he passes it on the way to Rani’s cremation die, they believe, into another world than the earthly one which they equate with ‘the nation for which they were fighting as a kind of heaven … not the end of real life but its beginning’.[5] And such stories also characterise Tamil political leaders such as Kuttimani (Kuttimani being the nom de guerre of Selvarajah Yogachandran). And it is through such an imagined gaze of liberation, following tutelage of Anjum, that he sees north eastern Sri Lankan / Tamil landscapes:

…, Krishan had the strange sensation that what he was seeing now was not exactly his own vision but the superimposition of Kuttimani’s upon his own, the superimposition of not just Kuttimani’s vision but the vision of all those many people from the northeast whose experiences and longing had been archived or imagined in his mind.[6]

I love that phrase ‘archived or imagined’ in my last citation, as if, despite Wikipedia administrators, there was no substantial difference between the product of a Tamil nation in imagination and the documents of that aspiration. Now, if one accepts that this novel is a kind of epic of a never-achieved, but in fable, modern nation – that of Tamil India – then we must pause before being certain that we understand all that happens or is said in this novel or the connections between the fragments of Krishan’s conscious and unconscious life that get thrown up therein.

This is a philosopher’s novel though before it is anything else and its take on embodied desire and its constraints as the index of freedom and achievement explain its insistence on the ‘slow progress’ of Rani’s body to its final burning. That burning is a kind of icon of the lost nation and what is burned in the pyre, as Krishan well knows, is:

Not just flesh and bones and organs but feelings and visions, memories and expectations, prophecies and dreams, all of which take time to burn, to be reduced to the uniformity of ash.[7]

But to burn is not just to be destroyed, although much depends on how gloomily you read the final phrases of the novel about a ‘message from this world to another that would never be received’. Is this a fatal stoicism or a call for renewal? You choose. I think the point is that messages are never received when you think they have a destination other than in shaping agency in human groups, a lesson the rather wonderful character, Anjum, knows of better than Krishan. The point is that those who hold power over us want us to forget the ‘disappeared’ that are the symptoms of their violent reaction to calls for any kind of freedom from oppression and this novelist blesses those mothers who will not let that happen to their disappeared sons and daughters.[8] Some forgetting is both necessary and therapeutic but Krishan knew the ‘crucial distinction’ between ‘the forgetting that takes place as a result of our consent, …, and the forgetting that is imposed upon us against our own will, which is so often a way of forcing us to accept a present in which we do not want to partake’.[9] My heart thrill at this sentence, it really does! The key image of the novel is the ‘slow progress’ of Rani’s body to its burning – one which takes the whole novel, though is mentioned only in the final section.[10]

The body is the subject and object of this novel as a thing and a focus of life. Hence we need to understand in detail the process of a Hindu cremation and we need to know the process of electroshock treatment, that was the first tool – in part chosen by Rani herself – of her need to escape images of things she has lost like her dear sons. The novel takes then very seriously the “ghosts and spirits and phantoms” that people see as the entities that are not the substance of the body.[11] In the end the ‘substance’ of those non-entities is alone ‘longing’ and you will be divided, if you are at all like me, about what such longing involves. In the end longing is about ambivalence I think and we need to read the passages around pages 284ff, very careful to come to a conclusion. I haven’t come to this conclusion. What is clear is that the novelist does not see Krishan’s guilt about his easy life in Colombo in comparison to the pains suffered in the Northern war as unnecessary or to be avoided. Rather it must e embraced if we are to see that bodies only learn from ‘actual fighting’ not the easy life of thought.[12] There is no alternative for instance than to learn what it means for a body to age and the story of Appama, Krishan’s grandmother, is there for us to realise that and to link it to the losses and traumas suffered by Rani and to admiration of people who fight.: ‘in a way it was hard not to admire the resoluteness with which she’d [Appama] fought against what was happening to her, …’.[13]

There is a lot I have yet to say about this wonderful novel but had better stop now. I will watch how the novel is evaluated in the literary establishment with interest.

All the best

Steve

[1] Anuk Arudpragasam (2021: 280)

[2] Arudpragasam (2021: 150f.)

[3] Ibid: 182

[4] Ibid: 182 – 185.

[5] Ibid: 244

[6] Ibid: 204

[7] Ibid: 286

[8] Ibid: 221f.

[9] Ibid: 227

[10] Ibid: 225

[11] Ibid: 280

[12] Ibid: 191-3.

[13] Ibid: 53f.

One thought on “BOOKER SHORTLIST: A ‘mode of existence more akin to that of ghosts than humans’: Tamils in Sri Lanka after the civil war and the ghostly but epic life of a nation that never existed: being a reflection on the philosophy of epic underlying Anuk Arudpragasam 2021 ‘A Passage North’”