A definition of an Ootlin by Jessie Kesson: “queer folk who were out and never had any desire to be in”. The novelist, poet and dramatist Jenni Fagan speaks of her upcoming memoir called Outling and the origin of that word in the writer Jessie Kesson at a reading performance of her adaptation of Kesson’s BBC Radio Play ‘You Never Slept At Mine’.

The programme for this event at the Edinburgh Book Festival reads:

Born in an Inverness workhouse in 1916, Jessie Kesson spent her early childhood in an Elgin slum before being moved to an orphanage and eventually being sent to work in service. Despite her inauspicious beginnings, she went on to become an acclaimed writer, often drawing on her early life experiences. Best known for her novels The White Bird Passes and Another Time, Another Place, she also published poetry, short stories and more than 100 plays including You’ve Never Slept at Mine.

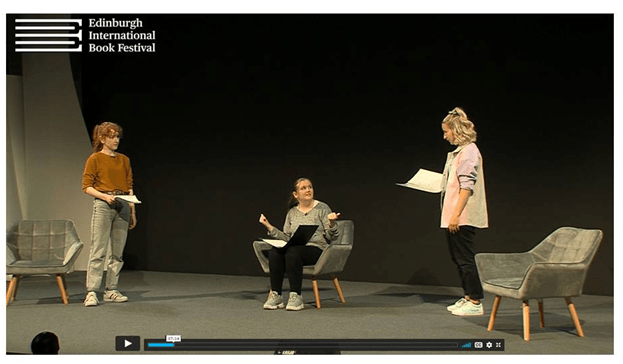

First broadcast on BBC radio in 1983 You’ve Never Slept in Mine provided a glimpse into the lives of young women in a residential children’s home. Today it provides the inspiration for a new collaboration. Stellar Quines theatre company along with actors Genna Allan and Chloe Wyper from the Citizens Theatre’s WAC Ensemble – Scotland’s first professionally supported theatre company for performers and theatremakers with care experience – have worked closely with novelist Jenni Fagan to create a masterful adaption. It is performed script-in-hand, followed by an on-stage discussion with the cast, Jenni Fagan and Stellar Quines’ Artistic Director Caitlin Skinner (who directs).

An ‘Ootlin’, Jenni Fagan says, elaborating on the definition by Jessie Kesson. is someone aware that the sum of all experience is a set of amazing, rich and different worlds These worlds are touched with pains and pleasures outside that expected in normative thinking and perhaps the more real for that, for they are not beings from ideology but visceral experience. Each world for each ‘Ootlin’ is one defined by yet one more individual experience of pain or joy. An Ootlin is ‘someone who creates their story without first seeking permission to do so’.

This story has the feel of Scottish fairy story – much richer (and more viscerally experienced) than those of England and less subservient to middle-class norms. The Chair of this event also said that that she felt that Fagan had opened up more ways in which writers, especially women writers (but not only they) can ‘share joy about the things that make you angry’. Not least of these things is the interdiction of anger by those who shirk responsibility for terribly bad systems like the care, mental health and prison systems., and the way these institutions become a predicted career for some too easily.’

This play is an urgent recreation of a radio play by Jessie Kesson but laced with the responsibility Jenni Fagan felt for creating a story of the ‘care-experienced adults’ in her play who had all sat in the same places – that is an overly oppressive care system – at different times and places. One of those – in care now – is fictional and feels her character fading in the light of the forceful writers (Jessie from the 1930s) who surround her

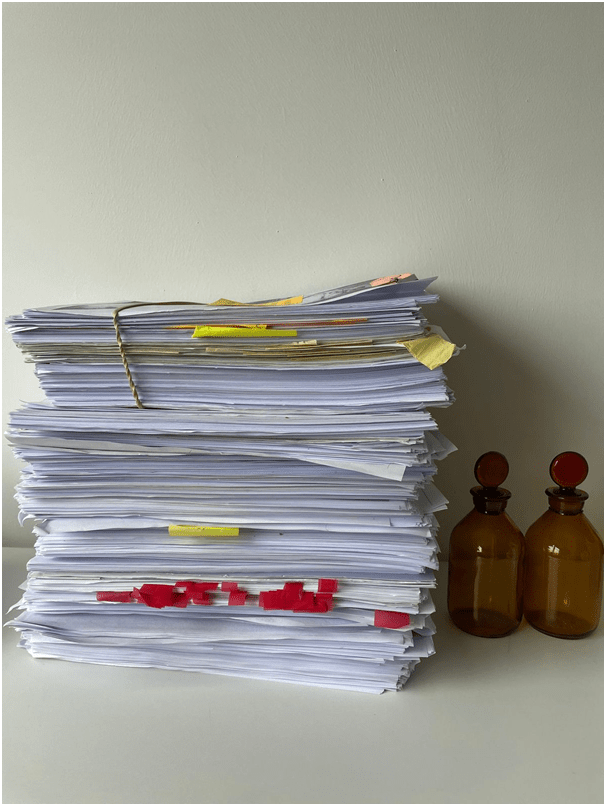

Set in the ‘sessy’, which is a very Scottish abbreviation I take it for an assessment centre in Scottish children’s social care are two avatars of the writers Jessie Kesson, in care in the 1930s, Jenni Fagan in care in the 70s and Jenni, a fictional character currently in care but imagined collaboratively by these two formidable writers. In this place Kesson tells a brief version of her own story, as does Fagan, rejecting the stereotypes that continually present the ‘care experienced’ as nothing much more than a ‘fuck-up of the system’. The only redress is for each Ootlin to tell her own story in her own way. Jenni Fagan is currently doing so and has assembled her pile of social work files for the purpose. Indeed she has shared a photograph of this pile on Twitter with the legend: ‘Social work files. Two decades exactly since did first draft memoir on typewriter borrowed from neighbour, very odd to be looking at it now, carried the manuscript around for twenty yrs before I could even look at it again’.

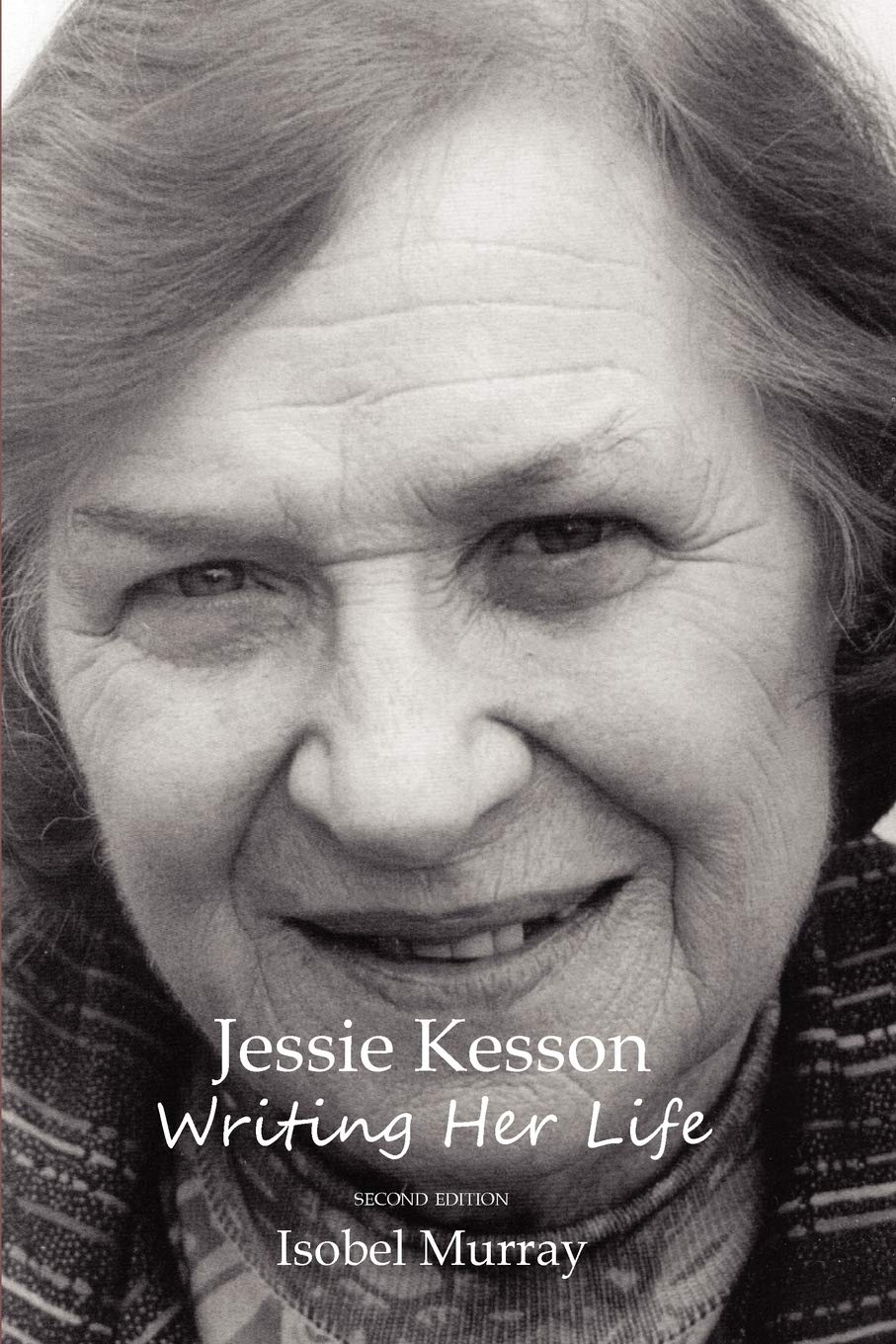

What an explosive publication these will make and how many eyes will open yet I wonder if much will actually change in a system where the voices of the care experienced are continually marginalised and disregarded, whether male or female voices. But this is perhaps especially true of female voices who are refused the luxury of anger that fuels some young men, if not to their advantage necessarily. Jenni Fagan has now published her third novel, Luckenbooth, on which I blogged enthusiastically. There is more to come – perhaps even, after tonight a dramatisation of Kesson’s wonderful The White Bird Passes, a novel Jenni Fagan first introduced to me when I attended her class on Kesson at Edinburgh Book festival.

Fagan has absorbed Kesson as no other writer has. Indeed to many she has remained unknown though she wanted ‘to write like Shakespeare’. Fagan looks back on ‘You Never Slept at Mine’ as relevant then, when she herself was young and NOW – the phrase is a version of the axiom about ‘walking in another person’s shoes’ and thus speaks of the indivisibility and specialness of each individual’s experience. Kesson’s words sum up what the play tells us about the experience of the marginalised who still prefer their queer nature to norms: ‘Nothing riles up human beings as much as another human being you ‘canna understand’.

There is something wonderful after all about being not understood by the norms of this binary society where real life is ‘Othered’ because it is complex and diverse. For Jenni Fagan the lesson is in this play. No matter how much the authorities lock you up and lock you in and keep reserving their right to ‘assess’ you – your presence and your voice – writers ‘always keep going’, living their artistic and their internal lives, using one to fertilise the other and make it relevant. Nevertheless she admits that ‘once you are in the system, you never get out, until you die’. And part of that system is one where a great intellect is nearly always thought to be that of the ‘educated white man’. Hence we need to revive Jessie Kesson and ‘the other Jessies out there’. I for one, as everyone knows, am proud to be a Jessie and would be prouder if I were a Kesson. We cannot go back to the panel at which Fagan was told by her the leader that she ‘was a considerable danger: both to herself and to all society’ and that she belonged in jail, that place which everyone thought her future tended. I cry when I hear that Debbie, an unseen character in this play, probably died in care as does Fagan’s Anais, who is NOT Fagan, in The Panopticon.

If you have chance to see this event before it disappears from the website, please do. It is a ‘love letter’ to Jessie Kesson but it is MUCH MORE than that. It truly is.

19 thoughts on “A definition of an Ootlin by Jessie Kesson: “queer folk who were out and never had any desire to be in”. The novelist, poet and dramatist Jenni Fagan speaks of her upcoming memoir called ‘Ootlin’ and the origin of that word in the writer Jessie Kesson at a reading performance of her adaptation of Kesson’s BBC Radio Play ‘You Never Slept At Mine’.”