The complex gendering of men and nets: a fantasy reflection on a recent exhibition at the City Art Gallery Edinburgh seen on 1th August 2021 with the assistance of Dealbhan le Eileanach’s (2019) Donald Smith: The Paintings of an Islander Stornaway, Isle of Lewis, Acair Books.

There is a brilliant virtual tour of the exhibition with names and dimensions of paintings (plus selling prices) on: Islander: the Paintings of Donald Smith | Museums and Galleries Edinburgh (edinburghmuseums.org.uk)

Why is it that metropolitan cultures (as true probably of Edinburgh and Glasgow as London) take such time to digest and evaluate new art from the Islands of Scotland? Nevertheless unlike London, at least Edinburgh is currently re-addressing this issue in some small way with this tremendously exciting exhibition, (re-addressing since this is not the first time City Art Gallery has supported Smith’s reputation as a Gaelic visual artist). Scottish art, after all, is already poorly represented in London (where they think Landseer was Scottish) whilst the reverse is not true of Scotland which owns sterling collections of English art and shows them as proudly as it does the great art of its ‘auld alliances’ with Italy, Spain and the Low Countries.

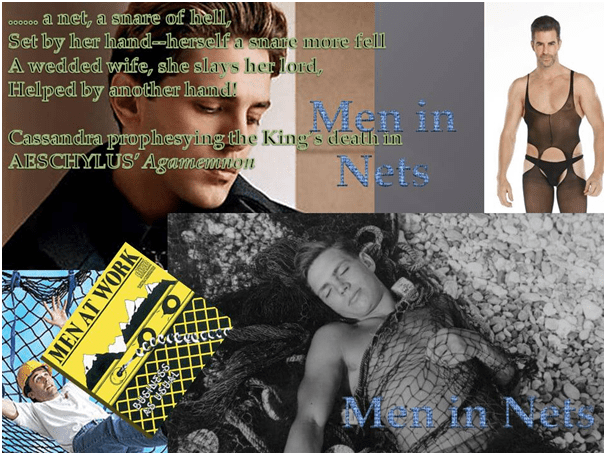

My take on the art of the islands however is here (if not personally) a very metropolitan one: approaching the themes of masculinity, natural life and work so prominent in these painting through a queer lens. This potential was suggested to me by an exercise I completed for a FutureLearn / Pompidou Centre course on Pop Art some time before I saw this exhibition, of which the product is shown below. I do not in this blog talk about the artist’s intentions nor the local reception of these great paintings but how they contribute to debates on masculinity as performed by visual artists, with or without an intention to make such a contribution. Personally I believe Donald Smith would not have proposed viewing his painting in this way but I wonder if this is what truly matters when we assess art, once the intentional fallacy (discussed it is true more in literary theory than in other arts or media) has been considered – something I consider, and have done since the 1980s, all the time.

The icon of the net – paradoxically in gendered thinking a tool of male work (in fishing and even – in classical times – land hunting – has always been uneasily related to its use as an emblem of art (where it also sometimes associates – as in George Eliot for instance with weaving and ‘web’ icon (possibly through the classical associations of the classical myth of Arachne which Velasquez (for one) exploited. Webs and weaving are particularly associated with women and female artists, since Penelope in the Odyssey.

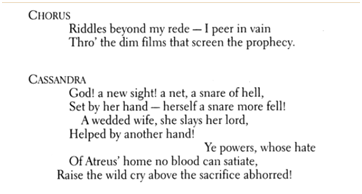

In Aeschylus’ Agamemnon those associations merge into a fantasy when the heroic anti-Trojan war leader’s murder by his wife, Clytemnestra, is foreseen by his Trojan slave-concubine Cassandra, in her divinely-inspired vision (of course treated as frenzied madness) in his bath with using spear and a hunting or fishing net (it is thought by some translators and commentators). Here’s the speech:

Of course it would be foolish to trace this image of snares and nets only as far as the Ancient Greeks. Ancient Hebrew culture bathes in it in the Psalms as a characteristic of godlessness:

They’re trapped, those godless countries, in the very snares they set, Their feet all tangled in the net they spread. They have no excuse; the way God works is well-known. The cunning machinery made by the wicked has maimed their own hands. The wicked bought a one-way ticket to hell. No longer will the poor be nameless— no more humiliation for the humble. Up, GOD! Aren’t you fed up with their empty strutting? Expose these grand pretensions! Shake them up, GOD! Show them how silly they look.[1]

But it is an icon sometimes of femininity too (as a kind of prototypical sinfulness sometimes equated with Eve) as the second quotation from Ecclesiastes confirms:

I find more bitter than death the woman who is a snare, whose heart is a trap and whose hands are chains. The man who pleases God will escape her, but the sinner she will ensnare.[2]

Nets are a snare to men whether as prostitutes in Ecclesiastes or faithless and revengeful wives and mothers (since after all Agamemnon did kill her daughter Iphigenia as a sacrifice to the gods) like Clytemnestra. And nets are an implement of manly use turned against them as if their very masculinity conspired against them. Of course my poor collage plays with this idea – from the use of nets as an implement in queer seduction, or wishful versions of that as in the early photograph from Vaughan and the pastiche of the man in ‘women’s’ (?) net stockings (such images are legion on the internet) I use therein. Of course nets can imply a tool of safety as well as destruction – an idea I also try to incorporate in my collage.

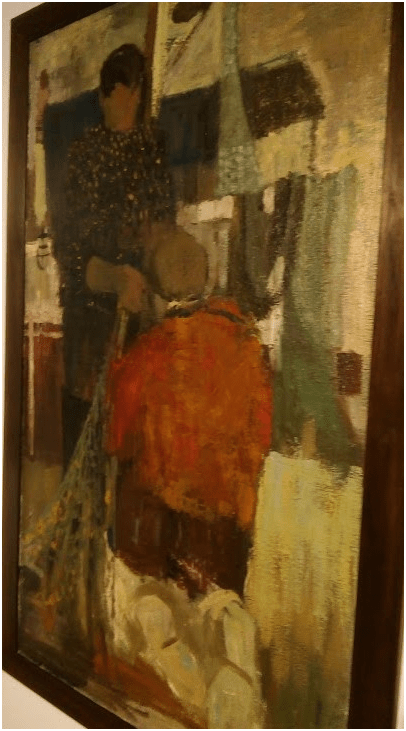

Visual art, of course need not adopt associated messages every time it uses an ‘image’ that various cultures have appropriated for uses in hateful thinking like misogyny and I do not think that transgender boundary-crossing is at all, as the awful LGB Alliance do, always a means of disrespecting women to be expected of men but is actually a means of adapting iconic symbols and wresting them away from uses that are pernicious like those used in misogynistic religions and cultures (or versions of such) since cultures can adapt icons to other more liberating meanings do. One of my favourite net paintings in Donald Smith’s show is about the mediation through nets and netting of heterosexual love and for me the net here from a painting from the 1960s is neither sinister nor evil.

The man kneeling before his wife in Da lasgair (Oil on canvas) is not captured and made subservient like Agamemnon but rather in co-operative toil, which for them the net represents, in the quest of ‘a living’ for them both. Note this is because netting (a kind of crude weaving) is not women’s work but shared work, even when the act of going out in the actualities of a cruel sea is not. The Scots Gaelic name of this painting translates as ‘Two flames’, and I see it as a symbol of queer love. Why queer though? You are entitled to ask. I think it is so because it plays so formally with gesture and proxemics, inverting normative gendered power relationships and rendering them up for reinterpretation – what queer means to me. Because nets in this island culture bind people together, of course, as well as separate roles or act as hunting snares (for fish). They hang all over the home made by this couple for each other making the work, lives and loves more co-operative – at least in this picture. It is a rare one, though because although Donald Smith paints women islanders – sometimes even in groups – these are much rarer than pictures of individual men captured (not by women) but in the delicate work of netting and mending netting that is essential to their being and living. Here work itself becomes a means of transgendering the culture. If women are subordinated in these islands cultures, as they most definitely are, it is not because of some pernicious ideology like that in Aeschylus and the Bible that services both monotheism (conceived in a male image) and misogyny. It is more likely to be because cultures and patriarchal relations are very complexly formed.

Hence we will find lots of ways of interpreting the omnipresence of men, nets and netting in Donald Smith’s paintings which need not invoke, although they do this also – understood in the same way as John Berger would have interpreted that project – as a protest at ‘…”the extinction of Europe’s peasant culture”’, as hinted by the artist Malcolm Maclean in his essay within the book I use in my blog.[3]

So my intention from now is to stop apologising for the wanton egotism of using my own little collage Men in Nets as an interpretive tool but to test instead the interpretive waters to see if they can or will yield the fruits of meaning I seek. Because for me these paintings are great studies of masculinity as an expression of the clothed individual male body or of a group of men formed into ‘a body’ – a theme I think essential to that neglected artist, Keith Vaughan, too.

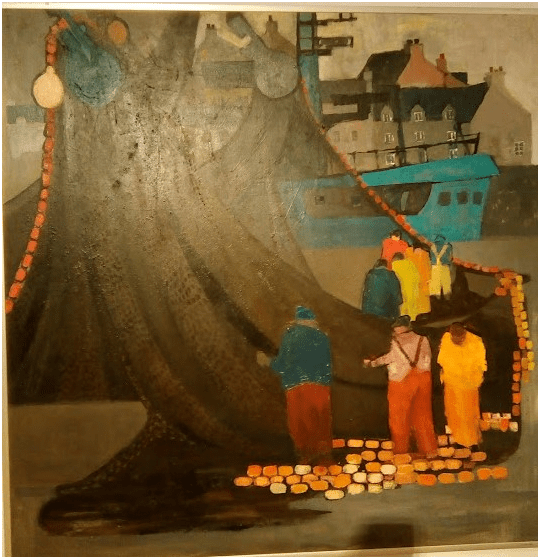

Of course the wondrous painting The Big Net is an ideal starting point for this discussion because it uses the huge net as both background and a means of connecting and positioning the male groups (and other individuals) in relation to each other. For instance there are two groups of men: one that stands in front of a raised section of the net facing us, and another within the net’s confines but in front of its rear raised section. For instance, it instantiates a secondary plane of vision between the picture frame and the material represented as at a depth (or distance) behind it

It is as if the net is utilised to indicate the receding ‘frames’ that constitute the illusion of progressive ‘depth’ in the painting. Yet otherwise the net is delineated by oblong shapes in white, orange and ochre, some in serial lines as if framing the net (and representing actual features of such a large trawl net) but which sometimes confuse our notion of realistic representation.

The effect of a near random grid of blocks of otherwise patterned colour below the feet of the group at the front may represent something ‘real’ in the scene but it is not clear what that object or objects might be. The patterned blocks also, perhaps because of that breakdown in their representational purpose, draws our attention to the flat surface of the painting itself divided between different sectors by vertical, horizontal and transverse lines. Sometimes they reduce the figures to similar patterns of colour patches (such as the largely internally unvariegated patches of yellow, red and blue that constitute the men’s clothing), which also reflect upon each other. This use of patches of colour makes for the effect of an abstract shaping of the surface of the painting that is at odds with other elements that demand both a depth perspective and a vanishing point associated with perspective in ‘realist’ or representational landscape painting. If the background of the town of Stornaway is realistic, then as we move away from it there is much more sense of spatial distribution based on relationships of patterns of colour brought to a viewer’s attention. In more than one way the ‘big net’ contains these men – by its linear boundaries and by depths and distances of perspective it is also used to portray, making of these male groupings something quite separated from the realistically captured quiet town beyond the harbour, that operates more like fantasy.

And this is because, in my view, the net is also iconic of a network of relationships between these men which shape their definitively gendered identity as male. It is as those connections (cemented by their common labour) are the net which contains them, further rising to engulf and overwhelm them. The men largely look downwards further contributing to the tension between the upward rising transverse surges of the hoisted net and that downward searching by the gaze upon that symbol of the threats that will swallow them whole. It seems instinct with motion, like the motion of the associated sea outwith the harbour. Is this because the work on and in the net also associates with the upcoming dangers of those seascapes to which the net and seamen both will later be applied. The sea, after all, has a tendency to swallow fishermen whole I suppose. And masculinity is often experienced as fringed with such danger that must be seen as either negligible or entirely fanciful as masculine identity often also eschews displays of emotion. If we see how Smith deals with portraits of unnamed individual men we might see the same dialectic.

In Iasgar Mor blocks of colour with too little sense of boundary from each other seem to engulf the sitter, an effect we also see in Balaich an Iasgaich, a painting of 1974.[4] In the former oranges constitute the space in which the man sits as well as his clothes and bare skin, whilst to his rear is a realistic harbour scene predicting the future use of the fishing net at sea. Our attention is drawn in this painting, as in many others of Smith’s, to the entanglement of the man’s hands in his own nets, such that it too, coloured in a similar orange seems to be pulling the seaman down into it. The classic example of this is that wonderful group of men, in which their emotional isolation from each other that is also, of course, concentration on task, is connected together by work on nets for a variety of uses and snares.

What grips and excites me in this painting is that loose net with any proximity to the act of being but only really visible in the limp and non-purposive hand of the man in the middle of the picture (see detail below).

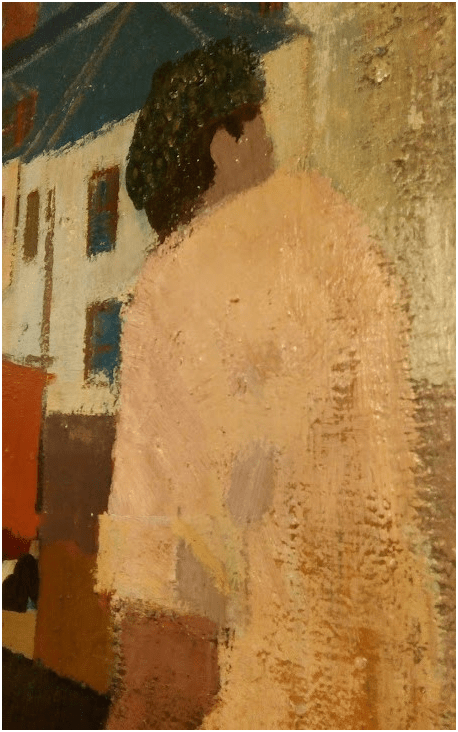

If limp and non-purposive masculinity in relation to men involved with nets is sought, my favourite would be the oil on panel painting named Stornaway (rather unhelpfully for identification purposes)

The limpness of the net seems to me almost to carry into something that question the ontology of the man and masculinity itself in my reading, that I feel through the way that the paint itself that creates the figure is appearing to disintegrate or be scraped off. Of course, even I wonder if this is a fanciful perception.

I can, of course, only state my view, however it might appear I am doing so, tentatively. When I look and respond to Smith’s paintings it is often to the feel (not necessarily either simply a sensual or haptic sense of touch nor abstractly emotional but both in interaction) about male groupings that feels like a kind of complex bonding that can’t be stated simply or normatively and is therefore queered. Of course I don’t mean by this that they are sexualised groupings, which they are, say, in Keith Vaughan’s various Assembly paintings, but rather that they excite us as bodies (meaning groups of men as well as individual bodies)that evoke embodied reactions not comfortable to some and certainly apparently intrusive. There are pictures of men with naked torsos at work that could be said to evoke a kind of homo-sensuality (rather than homosexuality) like the unnamed drawing of men at work digging peat in summer, but I found only this and my response may indeed be eccentric.[5] A better test case of what I mean is the well-known and beautiful painting, from the 1970s known as Salmon Netsmen (below).

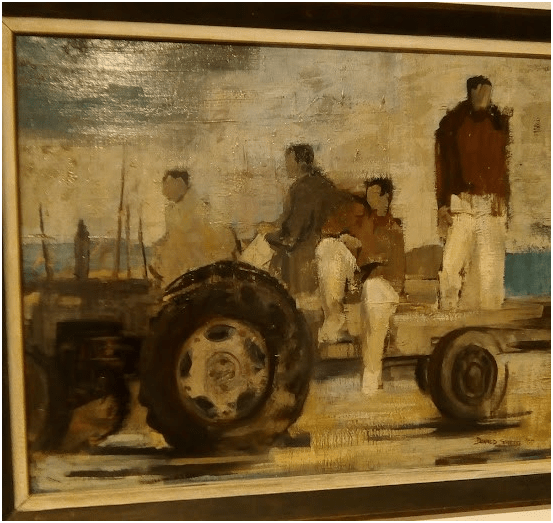

Salmon netting is a knowledge base of its own and we need at least a little knowledge (I have only what is at this link) to see why a painting with this title shows very little attempt to represent the nets used, although the distinctive orange can be detected in a paint mark to the left of the standing figure on the floor of the trailer to the tractor. The tractor is important since salmon netting is about setting nets in shallower seas and coastal areas rather than fully engaging with nets at sea. Hence the long waterproof boats of the men and the engagement of a tractor. What excites us visually in this painting is the coarse boundaries between figures that distinguishes them and their facelessness. What we see is flexed tension of a stand or the bend of a knee that feels to be about male bonding and diversions from it – in the isolated standing figure for instance. I certainly feel the texture of their closeness in part because the painting is obsessed by textures – particularly of the white clothing work by the netters, and the give-away huge hand of the standing figure which seems to communicate the fact that it is touching the cloth on which it rests. The man feels himself at his own boundaries. The central seated figures seem to lose boundaries between each other altogether.

There are lots of reasons to doubt whether Smith was really engaged in drawing the queer networking of bonds that constitute a shared but yet diverse masculinity but there other factors to remember too – not least the form of his inherited socialism (from his father) which emphasised how groups live as well as share. But whether others share my sense of an interest in bonds related to gendered experience being there in this painters work, I do love his painting for all kinds of other reasons. One I love in particular is a modernist representation of a gannet. I will end with this picture speaking for itself then.

See the exhibition. Buy the wonderful book.

All the best

Steve

[1] Psalms 9:15-17 Available at: https://www.bible.com/bible/compare/PSA.9.15-17

[2] Ecclesiastes 7:26 (NIV). Available at https://scenichillsblvd.wordpress.com/2020/05/15/more-bitter-than-death-ecclesiastes-726/ (a page that revels in its religiously authorised misogyny).

[3] Malcolm Maclean (2019:26) Dòmhall Safety in Dealbhan le Eileanach op.cit. 23 – 26.

[4] Reproduced ibid: 51.

[5] See it ibid: 84