‘Most of your sculptures are site-specific. The one you’re producing in Frankfurt is for the Schirn Rotunda, which is a special yet difficult space’.[1] The new extension to the old Fruitmarket, Edinburgh is ‘a special yet difficult space’. How does Karla Black make site-specific interventions here? Exhibition 7th July to 24th October 2021 Karla Black sculptures (2001-2021) details for a retrospective.

For a walkabout of the exhibition see: https://www.wallpaper.com/art/karla-black-retrospective-fruitmarket-gallery-edinburgh#0_pic_0

The Upper Gallery of the Fruitmarket, a long established space is a good place to start. Imagine a well lit (from top lights both natural and artificial) room where light cascades on a floor covered by pink powder around which a viewer can only walk but which they might wish to traverse or compromise its boundaries. All that is intentional on Black’s part: in the exhibition guide she is quoted as saying she wants the viewer to feel ‘…“at least an impetus towards a physical response” which in turn transforms into a “cerebral optical one”’.[2] This phenomenon I have sometimes seen described as the ‘haptic gaze’. Black herself says of her “haptic viewing” that she ‘tempted to touch them but at the same time the forbiddance is very palpable’.[3] The floor is coated with what’ looks like’ (but why?) a vast expanse of face-powder from the compacts women used to use in the 1990s but is actually a mix of basic conventional artist’s materials – plaster powder and powder paint, that mixed with water, or other fluid medium added would become pink paint. But, in part, we see what we want or need or are entrained to see and this is an axiom of Black’s work. Materials are, without any intervention by the artist, nearly always already in a relation of emergence as perceptual objects or concepts. Speaking to Katharina Dohm, she says:

It’s also important to note that the bulk of my art-making materials are traditional ones – plaster, chalk, paper, paint. There are little bits of cosmetics and toiletries, but the powder I use is plaster powder mixed with powder paint. The colors (sic.) play with the mind a little – we can easily be tricked into associations with confectionery, make-up, baby products, etc.[4]

We might also note that the mind is here utilising concepts that have been both related to conventional notions of age-appropriateness and gender. Black herself told Dohm that, as a feminist, ‘it bothers me greatly that only women’s work is gendered’ and that it is ‘an insult to me and to all women when my work is labelled as “feminine” because it’s perceived as slight, ephemeral, fragile, pale’.[5] Similarly associations with not only child-care and free play of and with the body are networked with something Other than the norm, which latter is silently but violently considered as ‘male’, ‘adult’ and ‘rational’.

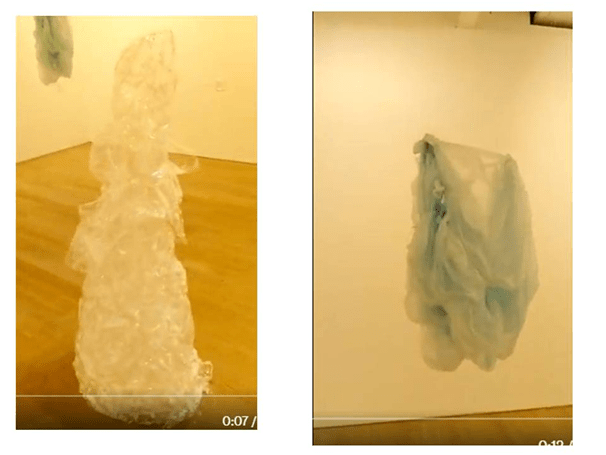

The retrospective of her work is, apart from the recreated work examined above, all mainly in the ground floor gallery to the rear of the building in a room that looks much as it did, to my eye and visual memory, before the building’s re-opening, but the arrangement of the work (should we call it curation or an aspect of the art itself) is by Black herself. It was my strong impression that in seeing this arrangement we become aware that a sculpture is not ever a free standing object singled out from an environment but that it moulds the space too between apparently single sculptures. This is made all the more apparent by ensuring that whilst some works are wall-hung as is conventional, others are suspended from the ceiling. One row of items, all of determinedly paper-thin (sometimes literally) flat appearance is hung in a serial line from each other such that to my eye a perceptual wall is created that dares the viewer to dive behind it, like Alice through a looking-glass, to the rear of the flat objects. Having noticed and felt the frisson this gives to our ‘haptic viewing’ we notice as well that there is a purpose to the irregularity of the dimensions of space between the works such that the perception of the plane on which they hang can emerge and also fade, depending on the proxemics of the viewing encounter.

Even issues about how each of the sculpture stands or hangs or ‘flies’ depend on the movement of the viewer’s body and the relationships in space between them in relation to each other and that body. The body lends motion, resistance and attraction to the sculpture, helping to shape it as experience. And, of course perceptually there is much that is done by appearance and the relation of appearance to basic desires including appetite and its manipulation, which again, as in the Alice books, plays games with the apparent size of associated objects, as with the huge slab of what looks like a confectionery (a black forest gateaux perhaps) in one of the pictures (all taken from my own video record) above.

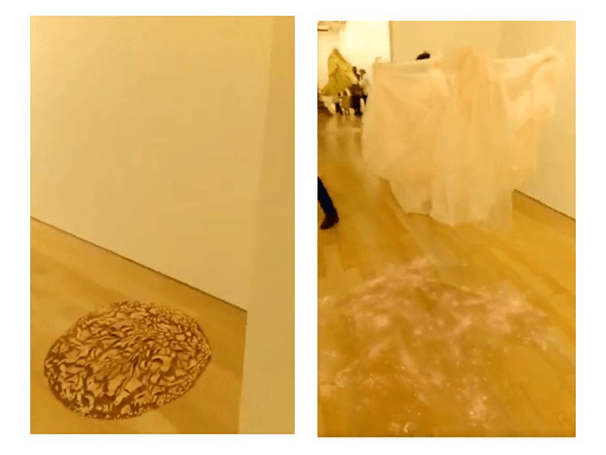

Sometimes the perceptual tricks are not only with objects where the relation of desire to the body is a wishful introjection or absorption (a ‘taking-in’) as in the confectionery illusions, so easily transformed into sexually appetitive structures, but are ALSO semi-excretory or post excretory. Thus it is with shapes that appear to retain the presence of objects from which they are the haptic and visible remnants. This may be a remnant of dirt but the employment of ochres and browns associate too with the excreted (and or vomited) that are sometimes patterned (accidentally or not – that is the game that is played). We will see this in the floor patterns which have a perceptual solidity and may indeed be in relief but not necessarily, as in the ornate brown pattern at a portal between rooms, discretely in a corner but inviting us not to tread in it. When these are patterned they are so by apparent relations of flow of some now dried liquid. We see that in the hanging work in the same room of some diaphanous fabric from which powder has dropped (randomly or not) on the floor below, creating another set of boundaries rising up around the hanging structure.

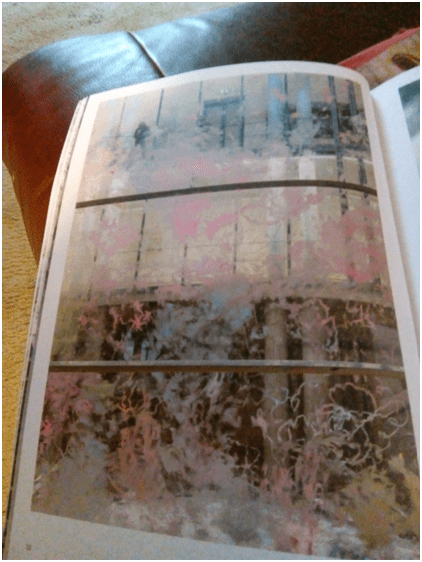

These are compelling when the marks (or emissions) are on transparent glass – as used very often in the Frankfurt exhibition which varied use of modernist pilasters and rectangular frame windows in a structure that rises. The windows are literally coated with materials that may be marks or projected sprays and which smear and ooze in order to obscure our vision of what lies behind the glass.

These effects can be seen in free-standing objects in the retrospective as with other flat surfaces that are reflective rather than transparent (mirrors in brief) that have their access to the appearance of the self (deliberately) obscured and introduce a critique of the frequently labelling of narcissistic versions of desire as feminine rather than human.

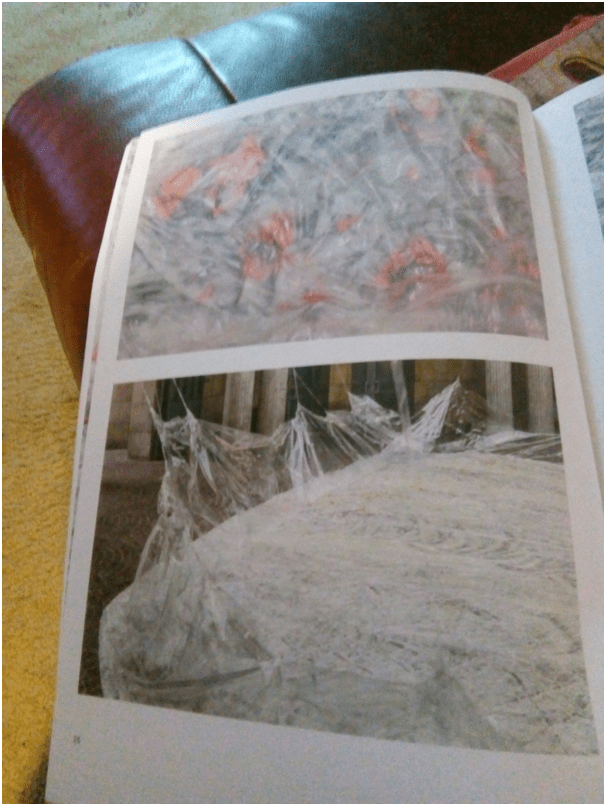

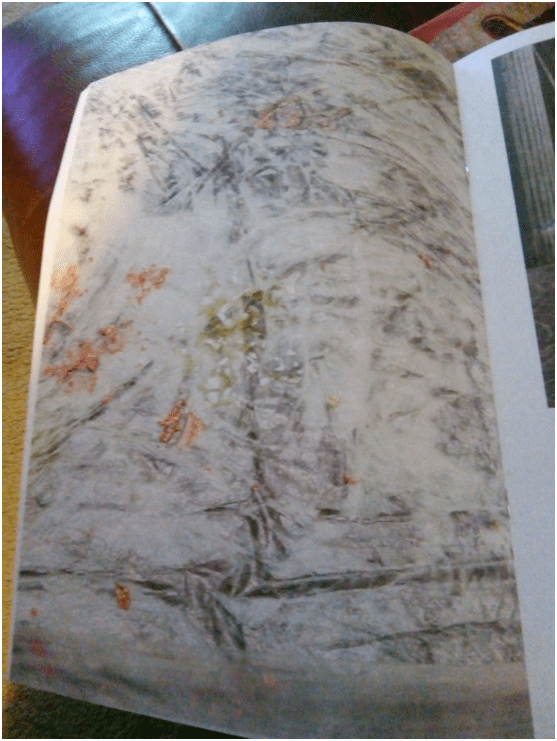

The Schirn work Conditions at Frankfurt the use of cellophane structures played with both the transparency and reflectivity of the substance, although mainly it is reflexion of light rather than image, of such large almost accidental structures as in these examples. This is even the more so where the colour patterns of the materials deposited on the cellophane are not just marks of varying colour, density and transparency but part objects themselves like shards of coloured transparent glass, associating with something that is harmful potentially. The examples cannot do it justice you need to see the wonderful book:Karla Black (ed. Katharina Dohm) Frankfurt, Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Verlag für modern Kunst.

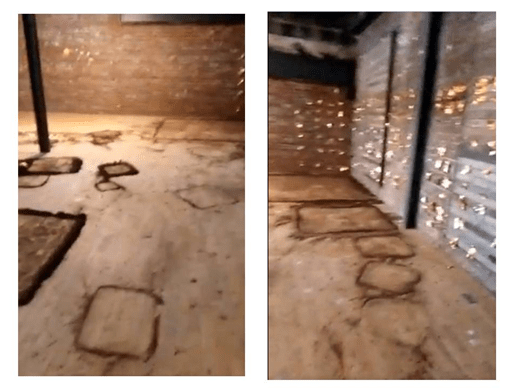

But the Fruitmarket in Edinburgh is ‘a special yet difficult space’ for very different reasons from the Schirn. It bears a weight of social, cultural history that is quite specific to its original purpose both when built in 1931 and in the rebuild of 1933. The extension of the ground floor exhibition space has retained its character as a warehouse and marketplace. The first work to benefit from this has these qualities of space and function in mind. It is Karla Black’s Waiver for Shade, which seems to have its genesis in recreating traces of the original space and function (the traces are, of course, not in fact extant traces but an aesthetic invention in themselves, and hence why they are recreated rather than presented as a ‘found’ blueprint). A comparison of the original Fruitmarket (though an external shot) with the image of a portion of the exhibition – both from free colour guide – tells us somewhat of the associations that might have been captured:

Certain feature of comparison jump out such as the slatted back board of the fruit vans that may have inspired the front wall screens we see in the artwork, but the main feature I notice is the omnipresence of stacked boxes being moved from the trucks to be stacked in the warehouse. The boxes not being uniform must have meant that stacking them challenged the ability of the handlers to find ways of stacking them that had no regular form or template, for it is the remnant of such stacked structures, at a time after the structures have been moved from the market warehouse, that might explain the traces of detritus the box like shapes on the market floor may have formed, as in the example below, where the detritus surrounding removed boxes may explain the difficult pattern of objects that are no longer present but exist only in the marks on the surface of the floor that their presence made.

Sometimes, as in the examples below, these form patterns – sometimes icons. My husband felt some of these shapes were phallic for instance. On the other hand they may be entirely random. Some shapes appear as monads with no apparent connection, as boxes laid relatively randomly on a warehouse floor may occasion. The relative thickness and density of these shapes may also betoken that these objects anyway may only have been related in their making on the floor at different times from each other rather being the marks of objects that once related simultaneously in this space.

The patterns in some cases appear to betoken the traces of a removed structure but whether that structure ever existed at one point in space and time cannot be intuited because of this. Nevertheless the shapes seem to pattern in ways that appear to connect the objects that made them.

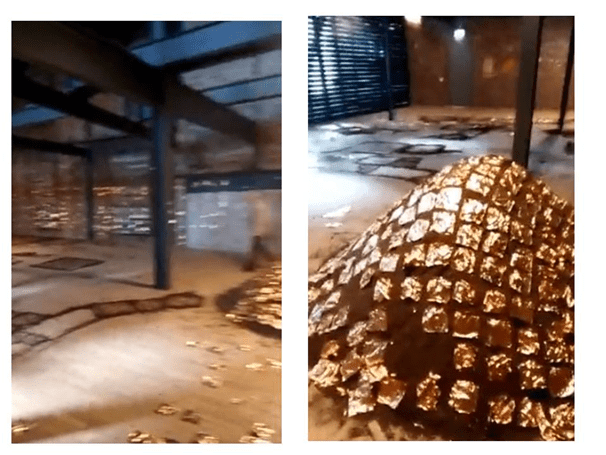

Are these the effects of art or accidental contingency in either space or time. We cannot tell but versions of such patterns, variegated by colour, and contrasting with the regularity of the wall’s brickwork, seem to betoken a more planned two-dimensional version of these floor surface structures as in the picture on the left above. And then there are the regular marks formed by gold leaf patterned on other brick walls, which also illustrate a dimension offered by stacked objects – height in this case, though their regularity and idealisation (perhaps the reason this detritus is gold and copper leaf rather than the ochre paint powder forming the floor patterns).

I have spoken before of the potential of these objects to represent deposits of waste and detritus. Indeed throughout the suggestion that they may be piles or remnants of decay, even human excretions are mixed with the same ambivalence about the excreted that Freud argued babies in the anal stage had to these offerings of the body, seeing them as precious gifts and only taught to see them later as objects of disgust by their parents. These were the ideas I began to form around the main object in this display, a regular pile of what must be brown plaster and paint powder but decorated with regularly sized gold and copper leaf. Meanwhile other forms of such leaf as well as brown smears of ochre in what i think is Vaseline form boundaries of detritus marking the difference between the spaces inside the artwork and those outside in which visitors feel able to walk

In the picture on the left immediately above see how the surface structure form the phallic shape my husband saw, or perhaps a finger pointing at the brown pile but never touching it. Much might be said here about relationships between emergent or vanished objects in space and time and the role of touch as an index of both attraction and, if avoided, repulsion.

Of course it is worth reflecting on whether we fear to touch art which Black refers to when she says (quoted earlier) ‘I’m really tempted to touch them but at the same time the forbiddance to do so is very palpable’ because of some inner ideal evaluation of it or because institutions of art forbid it, for good reasons of course. The extended digit yearning to touch but which never does touch the pile of what might be gold or excreta may indeed be an icon of this feature of haptic viewing. But I’d urge you, if you have access to Twitter to see my video of our tour of the work (the link will take you to it hopefully) and how both my husband, who loves art, and the young man guarding the work warn me off from treading too near the boundaries of the artwork.

‘Forbiddance’ is a strange word for repression and control but has a kind of socio-psychological appropriateness that could be said to be illustrated here. Forbiddance is a good word because learning to know what we can and cannot touch certain things is a task taken on in society by authorities including parents who teach us how to encode reality for good and ill. In many ways all art where the viewer must move to see the work from different perspectives and decide what are its boundaries are a kind of performance art that integrates the viewer but also threatens to deconstruct the artist’s intention for the work. Black herself says:

My work skirts in between mediums, gets close to painting, to performance art, to installation as close as it can before it recoils and remains a sculpture. Sculpture is its root, its discipline, its limit. Sculpture is so important to me because it is the medium that, from the 1950s on, exploded into all the new forms – performance art, land art, sound art, video art, happenings … I am trying to pull all of that experimentation back towards the careful, formal aesthetics of abstract modernist, autonomous sculptures and paintings.[6]

This is a very rich statement about the agency of the artist in the art work and it is clear that if experimental art extends itself too far into the haptic then the formal role of the artist is to ensure that there is also ‘forbiddance’ of touch implicit in the work itself. Hence those active resistances to viewer autonomy in this quotation. I think it is precisely over-appropriative viewers, as I may seem in the video, who are ‘pulled back’ from being essential to the artwork or form. We can get so close that we almost touch it but there is something necessary and psychologically active in our ‘recoil’ from actually getting too close. For art for Karla Black remains a ‘discipline’ where the artist and art institutions have duties to insist on the autonomy of art forms rather than to give them entirely up to the viewer’s whims.

I can’t wait though for the publication of the Fruitmarket Gallery’s book. I am waiting with disciplined (I hope) patience to learn, all a viewer, in the end, can. If I manage the discipline however, it may well be the first time. Lol!

All the best

Steve

[1] Katharina Dohm (2019-20) interviewing Karla Black in Karla Black Conditions (ed. Katharina Dohm) Frankfurt, Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Verlag für modern Kunst. (2016: 150)

[2] Exhibition guide but citing, without reference Dohm ibid: 17

[3] Ibid: 17

[4] Ibid: 17

[5] Ibid: 18

[6] Black quoted in Dohm, op. cit.: 19