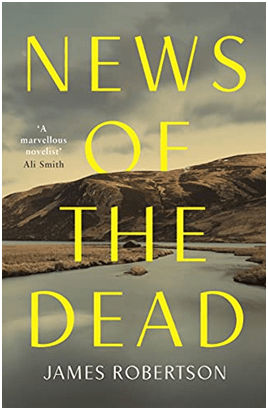

‘Any graveyard is full of stories’.[1] Attending an event and reading James Robertson News of the Dead Hamish Hamilton, Penguin Random House. Two very unequal experiences.

MAY CONTAIN SPOILERS, and it matters in this book.

Attending literary events can be a delight or it can be a trial. I felt this one to be the latter, but that is maybe because I find the chair of the event, Stuart Kelly, all too dominant in events he chairs. He tends to ask long involved deeply autobiographical questions – he returned to Scotland because Robertson’s The Fanatic convinced him that things were going on in his home nation and not just in London. Then he asks audience members to be ‘succinct’, without knowing how to model that quality himself, in their questions. Moreover, I feel he chooses questions from friends of the novelist too often and even one from his own mother.

But be that as it may, there was joy in this event which summarised the novel through use of a short telling film ‘

by Robertson and award-winning filmmaker Anthony Baxter which is premiered at the beginning of the event. Set in the Angus glens, the five-minute piece evokes the spirit of the landscape and the mood of the novel, forming the perfect introduction to a discussion about Robertson’s landmark book.[2]

It was indeed a very good introduction indeed and unlike this blog did not contain plot spoilers, which meant that my reading experience was a better one than it otherwise might have been, especially in relation to the ghost of the ‘dumb lass’, introduced in the first chapter as seen by a young boy but whose identity remains unrevealed to the end. Moreover, it matters because the turns of the three linked plotlines make this novel an urgent political intervention in post Brexit Britain under the threat of both a Covid-19 epidemic and global warming, not least because it chastises its readers to take the plight of migrants (political or economic) seriously and to learn some necessary historical facts in doing so. It was revealed that the story had a political turn at its end but not how and I won’t further spoil any future reader’s pleasure here. It was also let out by the Chairperson that this is a humane and funny book where character is played out in fully ‘rounded’ ways, to use Forster’s terminology. Even the possibly difficult-to-like character (Maya – another narrator – reads the book and tells us she does not like him) who narrates, unreliably no doubt, the main bulk of the story set in the early nineteenth century, Charles Kirkliston Gibb, has redeeming traits. Indeed he is redeemed in the story of his future after the end of his own telling of it, by another voice.

There are of course three layers of narrative in the novel, which I will attempt to describe below.

ONE: A third person narrative telling the story of Saint Conach of Glen Conach, who is not a canonised saint and appears to be an invention since, after all, Glen Conach is an invention though based on the Brae of Angus. From the outset we are to understand that this is a text owing much to literary sources upon which it is modelled and from which it may have ‘appropriated’ materials. That Gibb himself is an arch-appropriator – like Autolycus a ‘picker-up of unconconsidered trifles’ such as clothes and boots, such as those he found ‘wastefully unemployed in a press at Airthrey’.[3] Such jkes and malapropisms make the nature of theft and its relationship to ‘borrowing’ evident throughout. The theme emerges in a misunderstanding in fact between Gibb and Glen Conach (the laird and not the land itself) as Gibb surveys the holdings of the Manse:

I tried another, slimmer volume. “This also is new to me – Prophetiae Merlini Caledonici. No author given. I wonder is it a borrowing from Geoffrey of Monmouth? …

My host interrupted me. I was, of course, making a deliberate show of my erudition, that being the basis upon which i hoped to secure a long residency in his house, …

“Let me see that! There is nothing borrowed in this library. Either i paid for it or my father did, or his father. I have never been to Monmouth”.[4]

Forever nuancing the relations between plagiarism, copying, borrowing and theft is power for the course in explaining how otherwise penniless scholars might have kept themselves alive in 1809 and about acts of scholararship and translation itself. The Book (the word always italicised thus) of Conach itself derives (or is borrowed etc.) from different sources itself:

a. A purported English translation by Gibb of an original text of unknown authorship, although the original text (we are to learn) nor a transcription in Latin exist by the opening of the novel.

b. The transcibed research in the form of oral data gathered from local sources of an Edinburgh folklorist, who sounds to me somewhat like my hero, a great Scottish poet as well as academic folklorist, Hamish Henderson.

c. The inventions of various mediums of old stories that might have embellished, made conflicting versions or missed important information from these stories.

TWO: A first person narrative by Charles Kirkliston Gibb, which tells his own story as an itinerant scholar living off patrons who own works he purports to help them get thoroughly studied, translated and / or published. It is told in the form of a diary journal and thus is intrinsically unreliable in its subjective take on events that might have been coloured differently by a different storyteller. Moreover later parts of the narrative have interpolations from another author who is identified together with their views on the nature of literary invention much later in the novel. The overall effect is to make problematic the nature of what is fact or fiction, truth or invention. Even the notebook in which Gibb writes his journal diary has been ‘annexed’ from its former residence at Aithrey Castle.[5] These ideas are central to all of Robertson’s work (notably, of course, The Professor of Truth even in its title), given comic articulation here as the possible work of a ‘confabulating old windbag’.[6]

THREE: A modern day story set in the present years of the first importation of Covid-19 and the subsequent lockdown. This story is told by Maya, an old lady who tells stories to others about herself, about the Glen and about Conach to the Edinburg researchers. Her identity is implicated and complicated by those stories, not least because she increasingly appears to have a part in them. She even reads Gibb’s journal in order to elaborate his stories with data from other, even less reliable, sources, such as her own invention. She finally tells the story of the ‘dumb Lass’ to Lachie, who believes he has seen her ghost in the early chapters (beautifully played in the film by Robertson’s own daughter). The fallibility of stories, their sources and the processes of story-telling, including memory are constantly at the forefront here:

You should understand that none of this was remembered by the dumb lass. She had it told to her later by mrs Pirnie and Molly Skene and others who had different parts of it. She had no memory of how or where …. (and so on)[7]

Even the old lady telling the story tells Lachie, her primary reader can barely define what makes a story ‘true’ or to ‘profess’ truth:

The thing is, this story of mine is a true one. I will try to tell it as truthfully as I can, although there are parts missing and parts are probably not quite right. But there is no one else left who knows as much of it as i do, so where there are gaps you will have to use your imagination to fill them in. That is what i have done when my memory has failed me.[8] (italics in original)

Why we might ask ourselves should this theme of the fallibility of words that claim themselves to be truth be so interesting in these days. Our key answers will be political since the difference between fact and spin is immensely important nowadays and even forms much of an (unfortunately right wing) politics in the mouth of politicians like Donald Trump. In fact the theme was even more important in the nineteenth century when the questioning of story as synoptic witness emerged from Biblical criticism and studies of the contradictions of the Gospel stories. The truth of Christ can sometimes look as as little based in fact than that of Cronach, who is a fiction.

For me however, it is has another function which is queer the norms that purport to truth and to rescue the importance of tolerance of queerness, oddness and madness, even that of Cronach as his ideals fail him, particularly in his jealousy about the relationship formed by his man-servant Talorg with the woman, Meta. For Cronach clearly is in love with Talorg rather than Meta and masturbates as he sees them have sex: ‘he caressed the devil and spilled his seed on the ground’.[9]

I remember once congratulating Robertson for the accuracy of his picture of a queer man in his novel And The land Lay Still. There is nothing overtly queer in this new novel but the understanding of sexual difference of different kinds is important in coming to terms with Gibbs’ growing human knowledge. For instance the parson Dunning’s sexual alliance with his servant becomes understood but Gibb also shows us that Gibb is capable of understanding and sometimes participating in queer sexual relationships in his semi-drunken liaison with the atheist teacher Daniel Haddow. Haddow misunderstands Gibbs reference to himself and Haddow as being ‘the men they are’. This scene is more redemptive of Gibbs humanity and belief in diversity than any other passage. I will leave you with it. It’s lovely.

He looked at me. “Ah, Charles, the men we are. You do understand me, “ he said. “Or do you?”

His entire frame was shaking, i did not know with what emotion. He lifted the pig and indicated to me to present my glass, which he filled again. As he did so he steadied himself upon me with his free hand, and then he squeezed my shoulder in a manner that i could not mistake.

I have been misinterpreted in this way before. I neither welcome nor resent it. It is almost flattering. Other men, if they think of it at all, are frightened by what they conceive to be a bestial perversion. This is because they are frightened of themselves. Once, i confess, some years since. I allowed things to progress a little further than i liked in order to get a lodging on a winter’s night. On that occasion I was somewhat surprised at myself, but I was not frightened.

…

This passage stands apart in the novel because of its determination to refuse confusing norms with truths. Gibb is not only a realist but he sees that ideas of what is normal for males are not so clear-cut and may be contingent on other facts, like economic necessity. The point is that there are more things in the self than are sometimes admitted or allowed articulation. I find that a rather beautiful application of the theme which makes Gibb a more than interesting ad totally empathetic character.

I love this book. It tells wonderful stories and enables you to think about why we tell each stories and why we should value that mode of communication. Do read it. That will be much more important that watching the video of the Book Festival event. Here is a remarkable novelist and storyteller.

All the best

Steve

[1] James Robertson (2021: 368) News of the Dead Hamish Hamilton, Penguin Random House.

[2] See https://www.edbookfest.co.uk/the-festival/whats-on/reading-scotland-james-robertson-ghosts-of-the-glen

[3] Ibid: 14

[4] Ibid: 48

[5] Ibid: 13

[6] Ibid: 9

[7] Ibid: 328

[8] Ibid: 321

[9] Ibid: 313

One thought on “‘Any graveyard is full of stories’. Attending an event and reading James Robertson ‘News of the Dead’”