‘… his art passed out of fashion and into that dark hinterland of obscurity’.[1] Reflecting on an attempt by the City art Gallery, Edinburgh to revalue some of the lost traditions which help us to see why Charles H. Mackie should be seen as a great Scottish painter. With reference to, amongst other things, Pat Clark (2016) People, Places & Piazzas: The Life & Art of Charles H. Mackie Bristol, Sansom & Company.

Pat Clark is correct in arguing that Mackie is virtually forgotten, even in Scotland where more showy personalities with easier to trace links to the mainstream themes of the history of art take precedence. Duncan Macmillan deals with him, in his 1990 monumental Scottish Art 1460-1990 as a by-way in a chapter that concentrates on the Glasgow Boys and ‘The Colourists’, seeing him in association mainly with Patrick Geddes and the publication, The Evergreen, which were, he claims ‘very much part of this movement’. And thus a part in the margins of a movement considered more interesting and central inevitably becomes a ‘bit part’ – a kind of eccentricity subsumed by having a ‘colour theory’ (of which more later) of which the best Macmillan can say is that it is ‘by no means outlandish’.[2] Indeed he receives praise, says Macmillan, from the English artist and his collaborator in the Staithes Group, Laura Knight, herself somewhat faded in reputation these days (see my blog on a recent vibrant airing).

The link between Mackie and the Nabis, another movement in art that was killed off by a more obvious lunge in art away from the literary painting of narrative and symbol in modernism, is mentioned by Macmillan. There is more detail about it in William Hardie’s 2010 Scottish Painting 1837 to the Present, but only to hide Mackie under the vastnesses of Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s reputation and ‘circle’. Mackie’s literary bent is here however given full acknowledgement , discussed in a way that takes extremely seriously the Nabis interest in innovative uses of large patches of colour and intriguing combinations thereof. Nabi interests, together with a strong flavour of japonisme, led visual art into innovative and altogether subjective, literary and narrative investigation of colour and other cultural symbols, including those of religion associated with Paul Gauguin, who Mackie met, and Paul Serusier, with whom Mackie collaborated. But the ‘subjective, literary and narrative’ was killed off by modernisms sourced in the USA and powerful critics of the literary bent and with great power in the UK.

Clearly Pat Clark had, even from that point, some work to do to ask even Scots, used to having their artistic traditions ignored on large in the rest of the Union, to take seriously how innovative some of Mackie’s work is. This exhibition convinced me and urged me to read Clark’s book (she appears in the video played in the gallery). I cannot however feel that you ever get away from the fact that Mackie’s failure to articulate his vision in public words or commit himself to a consistent practice helps establish him beyond the role of a ‘curiously fascinating’ (to adapt a term from his wife used to describe the Nabis) outlier in art history that has only partly to do with being neglected as a Scot.

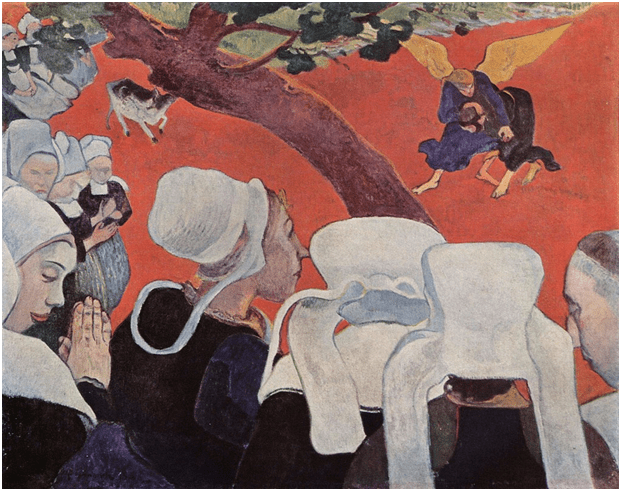

Serusier was the acknowledged intellectual lead of the Nabi movement, acknowledged even by better artists iin the group such as Bonnard and Vuillard. Maurice Denis saw him as on ‘a higher plane’ even in the Académie Julian in 1888. His use of colour to highlight the artist’s freedom of imaginative symbolic invention (most notable in his 1888 painting The Talisman) must lie somewhere near the otherwise hard to document ‘colour-theory’ which everyone agrees Mackie had though which he never committed to writing.[3] It was on visiting Serusier, that Anne Mackie (his newly married spouse) recorded some amazement at the technique of Serusier’s paintings as an example of the ‘most advanced French art and artists’ (whom she knew as “les Symbolistes”). She reacted to it with a kind of distanced enchantment: ‘their work seemed queer, yet it had a curious fascination in spite of the misshapen peasants and pink ploughed fields’.[4] The Nabis, following the example of Gauguin would work with patches of distinct colour that deliberately refused to be representationally mimetic but rather evoked the invention of the artist in a meld of idea and emotion, including the kind of estrangement from the norm that Anne calls ‘queer’. The classic example is of course Gauguin’s Vision Of The Sermon, in which Jacob is seen by the fascinated Breton maids wrestling the angel in a field stained a patchy vermilion, from which the priest turns away and down his gaze. The context of a rich folklore belief fed into the disruptions of meaning and emotion contributed by the artist, often to religious subject matter or folklore variations thereof.

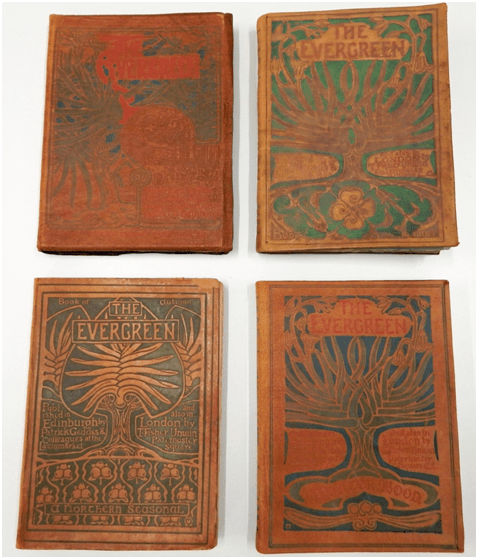

Pat Clark attributes to Mackie constant use of Serusier’s maxim ‘cherchez le gris’ but struggles, as anyone would, to define exactly what is meant by it. Mackie’s neighbour, James Cowan is cited as having listened to Mackie’s ‘wonderful views of his own on the subject of colour and theories on the subject which were based on a well-thought out plan’ but no description follows.[5] Much is made however of the fact that even having such a theory made him the but of jokes of contemporary painters in Edinburgh who Anne tells us ‘dubbed’ him ‘a faddist, a crank, an experimentalist’.[6] My own bet is that Mackie uses colour, at least in the first flush of his work with Patrick Geddes Celtic Revivalist movement as more than a means of seeking compositional harmony or visual effect as Clark seems to say. I would like, had I more knowledge, to say that he was part of an attempt to explore worlds beneath the norms and stereotypes of the Victorian Scotland of the Union, especially in relation to the uneducated and disadvantaged, whom Mackie advocated for throughout his life.[7] Just as Gauguin, Bernard and Serusier looked to Breton peasants for illumination and for the relevance of story, it is possible to guess at the potential for such work in Mackie’s equivalent interest in the folklore of the Celtic Twilight (as with W.B. Yeats) which allied him to William Sharp (Fiona McLeod) in the publication of that book of folklore, The Evergreen. Mackie designed the stunningly symbolic coloured illustrations on the leather cover, although its focus on the ‘evergreen’ leaves of the symbolic ‘arbour vitae, the tree of life (Aloe plicatilis)’, though this may have been his choice, is a visual examination of Geddes’ stunning statement about the importance of the association of the leaves of books and the continuity of green nature and the art of city gardening and building:

How many people think twice about a leaf? Yet the leaf is the chief product and phenomenon of Life: this is a green world, with animals comparatively few and small, and all dependent upon the leaves.[8]

As I pursued these ideasI I came across Graham Purves’ review of a 2019 book by William Shaw, The Fin-de-Siècle Scottish Revival: Romance, Decadence and Celtic Identity (from Edinburgh University Press). The review points to the fact that Celtic revivalism had much more going on under its cover of ‘fairy’ and ‘folk’ than the Scottish literary establishment allows. Take this description of a powerful entry into the debate about fin-de-siècle queerness:

Among the movements Shaw examines in his exploration of Scotland’s fin-de-siècle cultural scene are decadence and symbolism. Stuart Kelly has argued that in late nineteenth century Presbyterian Scotland, ‘where restraint and gravity became cardinal virtues,’ it was impossible for the excessiveness, indulgence and ‘fecklessness’ of decadence to take root. Shaw rejects this assessment, offering evidence that Scottish revivalist literature and art were often inspired by the styles and ideas of decadent writers, artists and thinkers across Europe, and often influenced those abroad.[9]

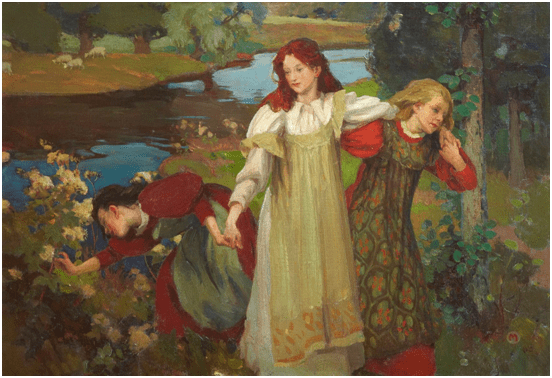

Yet despite the correctly aimed swipe at Stuart Kelly, the London literary establishment in exile, I cannot see YET how this perspective might illuminate Mackie, who is far from a centrepiece of Shaw’s book. However I have the book on order now it is due out in paperback later this year. Mackie’s Spring cover of The EverGreen for instance links the plucking of Spring flowers to the encapsulating and almost phallic serpentining figure of the tree of life. There is work to do here on the nature of ‘the leaves’ on which art id graphically displayed and a message about the necessity of escape from constricting English bourgeois conditions of Victorian art. Clark points to this in examining the Scottish folklore lying behind even the most apparently ‘Victorian sentimental’ of Mackie’s picture There were three maidens pu’d a flower (by the bonnie banks o’ Fordie) of 1897.

In earlier versions of this painting the reds, so prominent and compositionally important in the final version, are less significant, although marked in prominence by the hair colour of the central ‘maiden’. The story behind the picture is no sentimental story of flower picking (that recalled in the Spring cover of The Evergreen) as Pat Clark shows but of female subordination to male claims of both ownership and rights to exert sexual violence. Both of the girls around the central figure are murdered in the ongoing story by the ‘wee pen-knife’ of a ‘banisht man’ because they refuse his courtship.[10] The man kills himself with the same implement when he realises the girls he killed and the one remaining redhead he threatens are his sisters. Right at the heart of this story is sexuality turned queer by incest and the rapaciousness at the red heart of a taking possessive masculinity.

It made me look again at the murals Mackie made for Geddes at his home in Ramsay Terrace and which appear in reproduction in this exhibition. My photographs from the exhibition fail to capture the colours of these scenes, especially the all important use of reds, which Clark attributes to the discovery of ‘red lake’ in the period, saying that his ‘finest works, often in the later years, all carry a signature flash of red’.[11] But red is prominent here, often contrasting with ochres and oranges but also forced into violent contrast with green.

For me there are constant reminders of the violence and rapaciousness of the relationship here between human folk and nature, such that lines of red drip, one can almost see) from the wounds of the beech tree being felled, point the bloody submissiveness of the horses, the red one being placed focally, bearing away the already felled and now dead lumber. I find the grasping actions of the young man gathering the reddest of winter leaves equally ambivalent. Not though that I think this is a simple statement of the ‘cruelty’ of human relations to nature but a sure sign that in the cycles of life and death the life of the folk is not the sentimental thing it is often painted to be. It involves direct manipulations of the stuff of life and death. I don’t, that is, find these subjects sentimental but mature about the facts of life. Of course symbolic associations between dead and dying ‘leaves’ and the fresh green of the promise of revival, matter here.

But Clark and Macmillan are probably correct in saying that the lack of an articulation of his colour theory allowed Mackie to compromise it in his later painting and in using colour in more compositional than insistently symbolic way. It still varied his paintings from a simple mimesis but did not follow through on a commitment to narrative or symbolic elements. But with what power, they do this is shown in the almost universal liking that people express for Mackie’s late Venetian scenes, of which La Musica Veneziana must be my favourite.

Here compositional harmony is king but the interest in reflected and refracted coloured light almost reaches symbolic proportions and challenges the mimesis. The guiding metaphor is music of course but the effect of the magnified coloured light bursting above the gondolier is of an imaginative and beautiful passage in writing startling the harmony and opening it out to emotion. And the emotion can vary immensely in these wonderful paintings. Mackie expressed the effect thus, in a 1906 letter to Frederick Torrey: ‘Everything in that picture was meant and the feeling of music in saturated light is a very recurrent one with me’.[12]

In the exhibition comparing the study of the 1909 La Piazetta with the original the imaginative effect of the study was based on the use of a lamp standard shining through the night and fore-fronting two large human figures at a table. In the final one Mackie prefers natural light reflecting on flatter stone, smaller human figures and a focal position for one of the feral dogs of Venice. Suddenly, it seems to me that this underdog, in every sense, is sufficient illumination for the very human theme of what it means to ‘belong’ to a place people usually visit.

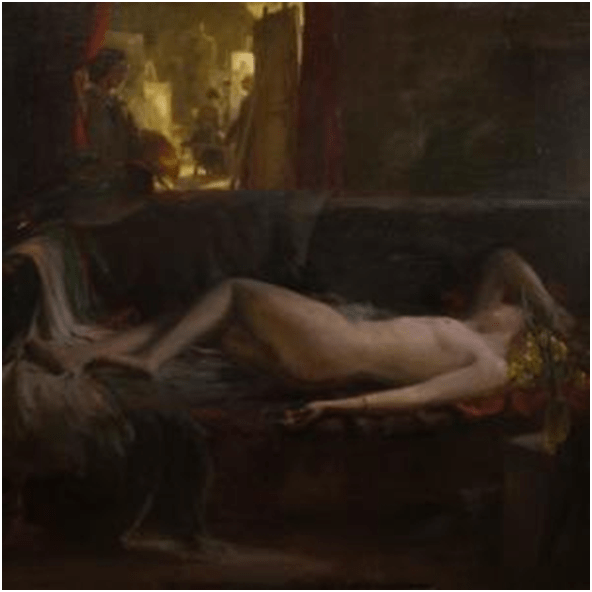

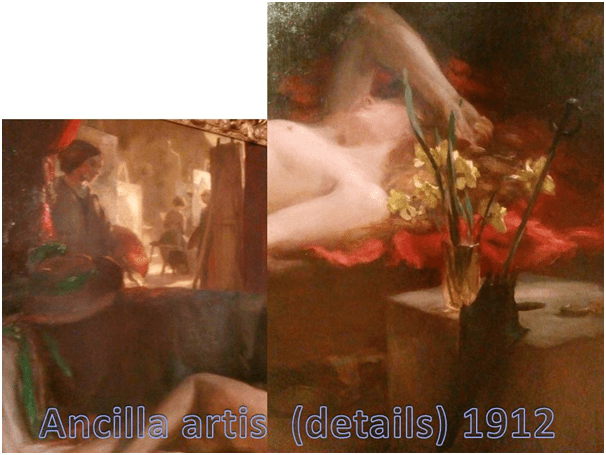

Mackie’s probably finest flourish was enough to cause a scandal in Edinburgh with the picture named an ‘immoral display’ and was entitled Ancilla Artis or The Handmaiden of Art. Of course the subject is the conventional one of the artist’s model captured in a moment where she is not working and feels herself free from the male gaze to which she is undoubtedly offered.

The painting was admired as the composition of a master colourist by The Edinburgh Evening News reviewer, which picks out the red curtain by which, it having been [pulled back, we access the model’s teeming workplace in the artist’s atelier from which she is resting in female company only]. The yellowing faded light (poorly reproduced above) of that distanced view forces our attention on the narcissi below this particularly beautiful female nude. There is a lot in this picture about the nature of the gaze and of privacy and seclusion in art, which again makes me admire this fin-de-siecle genius.

If you can get to Edinburgh to see this exhibition do. If not, buy Pat Clark’s informative book, which tells at least half of the interesting tale of his fin-de-siècle significance. Meanwhile await Michael Shaw’s book in cheaper paperback. It is at least £70 in hardback. Check with: The Fin-De-Siècle Scottish Revival: Romance, Decadence and Celtic Identity (Edinburgh Critical Studies in Victorian Culture): Amazon.co.uk: Shaw, Michael: 9781474433969: Books

All the best

Steve

[1] Clark (2016: 150)

[2] Duncan Macmillan (1990: 309)

[3] Frèches-Thory C. & Terrasse, A. (1990: 29f.) The Nabis: Bonnard, Vuillard and Their Circle Paris, Flammarion.

[4] Anne Mackie’s diary (undated) cited Hardie (2010: 121)

[5] Cited Clark (2013: 69)

[6] Ibid: 69

[7] See Ibid; 149. On ‘the urge to help the unhappy and the fallen’ in the slums of West Port.

[8] Cited National library oF Scotland webpage: https://www.nls.uk/learning-zone/politics-and-society/patrick-geddes/

[9] Graham Purves’ review published in Bella Caledonia on 3rd April 2020.. Available online at: https://graemepurves.wordpress.com/2020/05/01/the-fin-de-siecle-scottish-revival-romance-decadence-and-celtic-identity/. I have ordered the paperback which comes out later this year (thank you Graham for your campaigning).

[10] Ibid: 70

[11] Clark (2013: 72)

[12] Cited ibid: 119