Old Men in Love: Shakespeare’s Sonnet 34

Why didst thou promise such a beauteous day,

And make me travel forth without my cloak,

To let base clouds o’ertake me in my way,

Hiding thy bravery in their rotten smoke?

‘Tis not enough that through the cloud thou break,

To dry the rain on my storm-beaten face,

For no man well of such a salve can speak

That heals the wound and cures not the disgrace:

Nor can thy shame give physic to my grief;

Though thou repent, yet I have still the loss:

The offender’s sorrow lends but weak relief

To him that bears the strong offence’s cross.

Ah! but those tears are pearl which thy love sheds,

And they are rich and ransom all ill deeds.

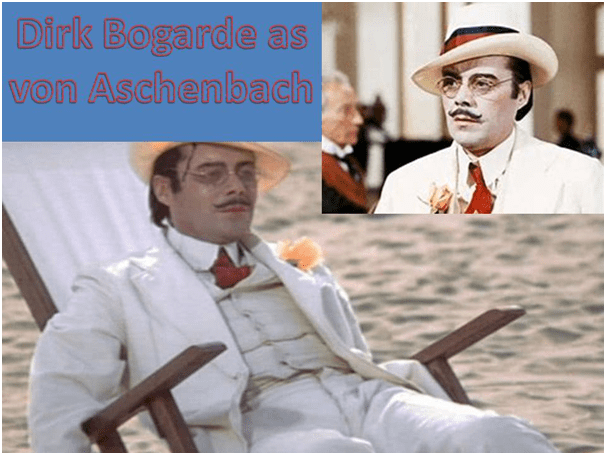

We far too often blame the pain we feel on someone else: no more so than when an older man falls in love with a younger man or woman and Shakespeare models this unreasonableness perfectly in Sonnet 34. The ‘young man’ of his dreams seems like the return of a sunny day after winter and is imagined as having persuaded the older man, who should know better, to travel out based on this ‘promise’ of fair weather. As always ‘promise’ does a lot of work here. It is allowed to seem as if the young man had actively promised something to the older man but had he? Sometimes ‘promise’, especially in terms of the English weather is just our wish of ‘fair weather’ projected into nature, a kind of wishful thinking of which the fact of the return of spring when winter seems endless is bout an icon. But such returns do not happen to mortal flesh, which when it ages, does not rejuvenate except by manipulation or deceit by someone – the art even of makeup employed by Aschenbach in Visconti’s version of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, so beautifully portrayed by Dirk Bogarde. The ferocious and unexpected heat of the scirocco makes the old man’s painted youth fail quickly whilst the young Tadzio, the object of von Aschenbach’s passion, remains immaculately beautiful.

The bad weather Shakespeare imagines, this being England not the Lido in Venice, is a watery storm but it’s effect is the same to rob the ‘old man’ of the dignity that he might have retained had he worn a ‘cloak’ that might protect him from ills he ought to have known about. But the issue is that old men in love, and it may apply to women as well I don’t know, feel they deserve the illusion of being lovable still, of engaging the passion of another, however unlikely that might be.

If your face is now ‘storm-beaten’ and lined by that experience, one ought to know that some storms can’t be predicted and are, anyway, more likely than not. Taking a ‘cloak’ to keep dry (and somewhat disguised moreover, is just part of the wisdom one ought to have acquired – but no! The fault is that of the ‘young man’ and old men compare their suffering to the most immense of exaggerated models – even to Christ carrying the cross to Golgotha – and no apology from the young man will suffice to cover the fact that the old man is a ‘disgrace’ in the eyes of others:

The offender’s sorrow lends but weak relief

To him that bears the strong offence’s cross

My italics

And such ‘base clouds’ of contradiction to an old man’s dignity, his failure to dare show his face, are as likely to have come from his unguarded, nay deluded, behaviour. You are no doctor, he says to him, and you cannot make me well. Shakespeare’s old men are of course wilier than that and may cast blame in the hope of a strong recompense. After all the young man owns a ‘pearl’, that of his chaste (or at least apparently so, sexuality and it will pay all the bills. But there is no doubt that the cost of the old man’s forgiveness, where there is in reality nothing but his own faults to forgive, like that other ‘foolish fond old man’, King Lear, is that the young man should feel guilty about his own beauty, self-confidence (‘bravery’) and immaturity – in short the very youth that attracted the ‘old man’ in the first place.

More in sorrow than anger

Steve