‘Eventually, I landed on Frantz Fanon. … In my disavowing I forgot who I was in the white frame of reference. The truth was that the Soli of 2003 was black’. [1] Getting implicated in a complicated story of intersectional oppressions: a reflection on Mohamed Abdulkarim Ali (2019) Angry Queer Somali Boy: A Complicated Memoir, Saskatchewan, Canada, University of Regina Press.

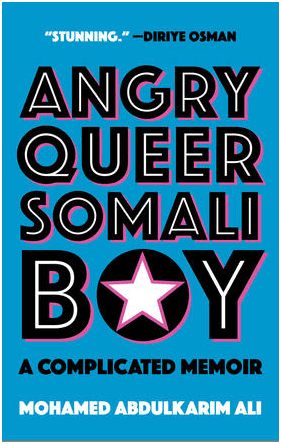

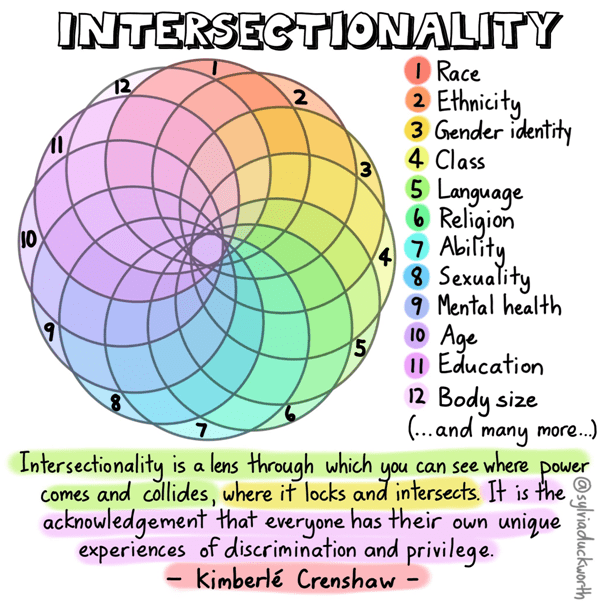

Hasan Namir, an ‘Iraqi- Canadian’ queer writer in October 2019 (according to Wikipedia) writing in Quill & Quire, the online magazine of the Ontario Council for the Arts finds much in Ali’s memoir with which to identify but does not see the identities in conflict in his and Ali’s case as the same. In that sense Ali’s book is correctly called ‘intersectional’, however contested that term, since it depends upon so many identifications, the links and gaps between which can be as accidental as they are variable in their interaction, but not always. Hasan says:

When I first read his book, I related to Ali so much: we both come from Muslim backgrounds and are queer, struggling to reconcile our conflicting identities. Ali did so while moving through different cultures and countries – from Somalia to the United Arab Emirates, then the Netherlands and, finally, Canada….

…. Angry Queer Somali Boy illustrates various intersectional experiences. One of the most heartbreaking moments involves Ali’s recollection of his sisters being circumcised. “I remember going into their bedroom, I remember seeing their legs tied together so everything heals properly,” he says. “They were stationary, such a contrast from so vibrant to so docile, so exhausted.

Ali’s own circumcision is also painfully described but the awful passivity he felt in front of his sisters’ pain is the more telling I think, and, as Hasan suggests, tells us something of how feminine identity touches upon masculine identity: whilst watch the muscles of ‘hulking men throwing each other around’ Ali finds in himself not a model of strength but weakness ‘for not rushing in to aid my new sisters’.[2] Later at school, he will again paradoxically find girls a better model for a complicated mix of belief in both personal beauty and ferocity, which is miles away from the bullying physical activity of boys.[3] This is reinforced in his knowledge of the rape of their own daughters by the weakest of Somali uncles.

So we do not look only to identities that people experience directly in intersectionality but to those experienced also relationally. This gives even more importance to the fact that acknowledgement of identity owes a great deal to cultural models of relationship that are either assumed or learned. Hence the import of learning from Frantz Fanon what it means to know one is ‘black’ through social practices, even those like sexual intercourse, that pretend to privacy. The section on how Ali learns about how ‘interracial gay sex’ is modelled, for instance, is fascinating and the excursion from there to understandings of colour symbolism across a wider frame of reference, tracing it from Graeco-Roman origins, through its borrowing by the ‘early Islamic caliphates’ that gave the lie to the tendency of black Americans in the twentieth century, such as the conversion of Cassius Clay (a good Romanised name to Mohammed Ali) because there was a (false) belief that Islam ‘lacked the racist history of Christianity’.[4]

But complex interactions between queer sexual and gender identities, race, culture, ethnicity, class, work role and status, political identification and nation mix too with behavioural categories and labels such as those employed in mental health and social labelling, particularly around both specific and generalised ‘addictions’. But even wishes are addictive and misleading. For instance, apparently welcomed into a Italian-Canadian family and given a role to match, he learns that his role is neither based on love nor community of values but socio-economic relations that favour the white privileged group and the cultural knowledge about their own interests that appears to have been ‘naturalised’:

When Venezia’s mother offered me the apartment on the side of their house, I was elated. … what she was after was a tenant who would forgo a lease. This came back to haunt me as I slid into my second stint of homelessness. …/ I felt used.[5]

Even recognising how and why other oppressed people become sensitive to objectifying identity labels can help shifts in the relations of power between the forces that maintain and challenge oppression. For instance an old West Indian Canadian lover, Tyrone, attempts to kill Ali when the latter unknowingly uses the word ‘junkie’ to described users of opiates, allows Ali within the same (and final)chapter, to realise that describing himself as ‘an alcoholic’ might register the beginning of a new positive identity rather than the reverse.[6]

Yet the lesson of the book is that privileged groups give up stereotypes that blame the victim for their own oppression. Continually harping on, apparently with admiration, at the way Ali faced a home environment in which they wonder if it was ‘tough growing up there’ they can listen to Ali explain how ‘the intersection of zealous policing, poverty, underfunded schools, and overworked parents’ lead to the social ills of oppressed residential areas they still know ‘nothing of the ghetto beyond what they saw on TV’: “I never hear anything good about the place. Was it difficult for you?”…[7]

It is no good to just ‘be yourself’, as the phrase commonly has it, without considering the ‘frame of reference’ in which that self is defined and sometimes confined, this book tells us. And ‘frames of reference’ can oversimplify as well as under-simplify oppression. We still need to understand why; ‘One in two white women voted for Trump, yet white feminists never tired of reminding black women that gender superseded race’. And why, even in a commune ‘people revert to their hatred of Jews’.[8]

All the best

Steve

[1] Mohamed Abdulkarim Ali (2019: 117)

[2] Ibid: 14

[3] Ibid; 47

[4] Ibid: 95. See the colour symbolism section about ‘interracial gay sex’ from page 94.

[5] Ibid: 157f.

[6] Ibid; 183 – 189

[7] Ibid: 116

[8] Ibid: 173

2 thoughts on “‘Eventually, I landed on Frantz Fanon. … In my disavowing I forgot who I was in the white frame of reference. The truth was that the Soli of 2003 was black’. Getting implicated in a complicated story of intersectional oppressions: a reflection on Mohamed Abdulkarim Ali (2019) ‘Angry Queer Somali Boy: A Complicated Memoir’.”