‘ …“second place” pretty much summed up how I felt about myself and my life – that it had been a near miss requiring just as much effort as victory but with that victory always and forever somehow denied me, by a force that I could only describe as the force of pre-eminence’. [1] A reflection on Rachel Cusk (2021) Second Place, London, Faber & Faber.

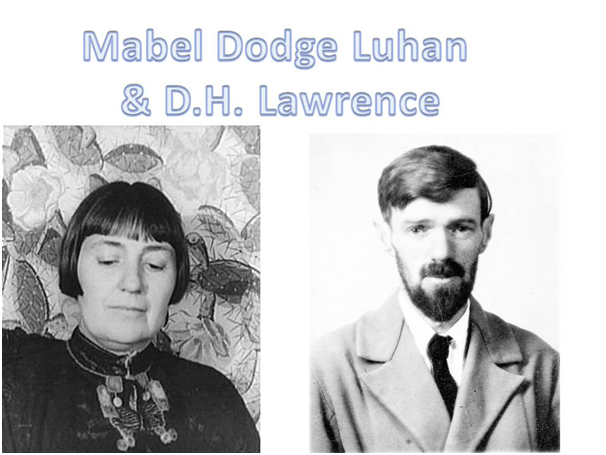

No-one sets out to come second in a race and narrator of Second Place seems to see herself as destined to always do so, in the shadow of others who seem predestined to always come first in the race. The narrator is known as M and the author lets us know that the story told owes somewhat to an already existing story, a memoir by Mabel Dodge Luhan ‘of the time D.H.Lawrence came to stay with her in Taos, New Mexico’.[2] M’s story in the largest part tells of a visit to a second home built in the grounds of her own primary home, and thus christened by her and her husband, Tony, as the ‘second place’, of an artist, L. That L is not exactly Lawrence however is made clear by the fact that L is a painter and though Lawrence did paint pictures he valued, he is, of course known primarily as a novelist and poet, an artist with words not coloured pigments. Yet towards the end of his life Lawrence renewed his work as a painter, producing images that now mainly reside at Taos that English critics branded ‘indecent’ and include many naked men and women mixed together in acts of sexual congress, of which a number of good examples (from the ‘forbidden art’ collection at the Hotel de Fonda at Taos) can be seen in the blog by Pat Keenan at this link.

Although I sense aspects of some of the stereotypes that pass in the critical literature as aspects of Lawrence’s personality in L, I think neither the paintings of D.H. Lawrence nor his literary art ought to shed any light of those by L described in the words of this novel. In this respect I agree in small part with Anthony Cummins review in The Observer, although I think he takes too far the dependence of the Cusk novel on the Luhan memoir, although it is nice to know that I could read the memoir online and even nicer to have a link to it in the following statement by him. He says:

While reading Second Place together with Luhan’s florid memoir (freely available online) shows the novel’s more jarringly melodramatic elements to be preordained, it also casts doubt on Cusk’s decision-making, since the book doesn’t fully make sense without reading Luhan, and even then it’s a close thing. Yes, Luhan addressed her memoir to the poet Robinson Jeffers, but does that justify Cusk having M continually address a never-explained “Jeffers”? Is the fact that Luhan married a Native American man reason enough for a passage on how M’s husband looks like a Native American?[3]

I enjoyed the novel a lot more than I expected, when I had not from the summaries of the novel expected that. Cummins’ strategic putdowns –‘melodramatic elements’ for instance – have not made me attempt to read Luhan any more than I did after reading Cusk’s endnote nor worried overmuch about whether or not ‘Jeffers’ is Robinson Jeffers, the correspondent in Lorenzo in Taos. There is a studied attempt at clever show in this review that makes me much happier to see the novel treated as a novel by the novelist, Sam Byers, in The Guardian’s review.[4]

Sam Byers may stress overmuch the depth of the analysis of gender per se in the novel I think. Certainly it is to men that M too often takes ‘second place’ where the man be her husband Tony, who is even first choice as a model to be painted by L, or L himself. Being first is a matter of feeling powerful in this novel and of feeling ‘free’, and both words ring the changes through this novel. People are agreed, even men of her closest acquaintance like Tony, that M has ‘power and teller he that she can ‘underestimate’ (her) own power’.[5] But freedom is often discoursed about as a particular male quality, even in art:

There is no particular reason, on the surface, why L’s work should summon a woman like me, or perhaps any woman – but least of all, surely, a young mother on the brink of rebellion whose impossible yearnings, moreover, are crystallised in reverse by the aura of absolute freedom his paintings emanate, a freedom elementally and unrepentingly male down to the last brushstroke. It’s a question that begs an answer, and yet there is no clear and satisfying answer, except to say that this aura of male freedom belongs likewise to most representations of the world and of our human experience within it, and that as women we grow accustomed to translating it into something we ourselves can recognise. … to the extent that some aspects of me do seem to be male. … Yet I never found any use for that male part, as L went on to show me later, in the time I will tell you about.[6]

This convoluted quasi-reasoning runs through the novel, adding up so often to a kind of androgynous message that displaces women from holding power and experiencing freedom solely as women, without acts of ‘impersonation’ (a word in the unquoted bit of the passage above) of male personae. And it explains why M continually tries to put L into ‘the second place’ (the home she and her husband built and whose ownership she impersonates in asking L to stay there. Of course the power of having and controlling a ‘second place’ and gifting it to men otherwise apparently pre-eminent over one, as a woman, artist, lover or model, comes in the novel to play games with the chase of L. Like Mabel Luhan, M thinks of the ‘second place’ as a home-base for pre-eminence, if not in art, but as housing art and artists: ‘… – the higher things, or so I thought them, that I had come to know and care about one way or another in my life’.[7] But using one’s second home – a home anyway really owned by your husband – as a means of drawing to yourself ‘communication … with notions of art and people who abide by these notions’ is a precarious race to come first at or class to be the top thereof, especially when the invited artists end up apparently preferring husband Tony to yourself.[8] And the scenario she generalises in these words, or similar, appears to be being reproduced when Tony is chosen as L’s first model – from then on M can only have ‘second place’.

This explains M’s delight to find that L’s portrait of her husband diminishes Tony: ‘… – he had made Tony tiny’.[9] That comic jingle playing on Tony’s name and belying the physique in tony to which we are otherwise treated in the novel is made the more heightened – one of those ‘melodramatic elements’ as described by Cummins – when M disobeys Tony, wears the dress she first wore to marry her husband to be painted by L.[10] Of course M comes a cropper. The scene is almost indeed a pastiche of that scene when Max’s second wife in Du Maurier’s Rebecca is tricked (by Mrs Danvers) to dress disastrously as if she were trying to take the role of first place in Rebecca’s party frock.

Yet M does confine L eventually to ‘second place (if not Tony). After L’s stroke, M takes a commanding role – but whether in ‘first place’ is doubtful – whilst:

… the end result of it all was that L stayed exactly where he was, in the second place, because there was nowhere else for him to go. He had no family and no home, and very little money, and although by then it had become easier for people to travel, we could find no one among his friends and associates prepared to accept responsibility for him.[11]

Of course L chooses freedom but only at the cost of his last word in the novel being an admission to M that he would have been better accepted the relatively powerless position of being in M’s ‘second place’: “I miss your place. … I wish I had stayed but at the time I wanted to go. … This is a bad place’.[12] Better then, for L, a ‘second place’ allocated sympathetically by M than a ‘bad place’, where he dies somewhat in the manner of Francis Bacon.

As a comedy in which power shifts in ever so many ways, in which a feminist analysis is pertinent and important but not unqualified by the ironies of the power actually exerted by M, and where, importantly M must learn to yield to her daughter, however keeping her to at least to the end of the novel in the ‘second place’, but we suspect with the wealth bequeathed to her through L’s night painting of Justine and her mother, not for much longer than that. And the play with gender and the feminising of men is yet another important strand of this novel, whether it is L ‘going through the change’ … ‘Like a woman?’… .[13] Or the fact that ‘the question of male and female felt somehow theoretical in (L’s) presence … because he made disregard for convention so apparent’.[14]

Indeed I think there is a lot of intersectionality in this novel of a kind I only brush the surface of here, and a lot about class that matters more than I have suggested. But surely it works for me because of the evocation of L’s portraits and even more his landscapes. I long to SEE his night paintings. In them the ‘power of illusion’ – to which M points –is even more what this wonderful novel offers.[15] I loved it, despite myself.

All the best

Steve

[1] Rachel Cusk (2021: 165)

[2] Ibid: 209

[3] Anthony Cummins (2021)’ Second Place by Rachel Cusk review – psychodrama in the shape of a social comedy’ in The Observer (Sun 2 May 2021 09.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/may/02/second-place-by-rachel-cusk-review-psychodrama-in-the-shape-of-a-social-comedy

[4] Sam Byers (2021) ‘Second Place by Rachel Cusk review – exquisitely cruel home truths: The deeply gendered experience of freedom is cunningly exposed in a shocking interrogation of art, privilege and property’ in The Guardian (Thu 29 Apr 2021 07.30 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/apr/29/second-place-by-rachel-cusk-review-exquisitely-cruel-home-truths

[5] Cusk (2021; 3)

[6] Ibid: 11f.

[7] Ibid: 22

[8] Ibid: 23. Note by the way the conversation with l where m makes it clear the ‘the house and land belong to Tony’ (ibid; 119)

[9] Ibid: 113

[10] See ibid: 157ff.

[11] Ibid: 175

[12] Ibid: 207

[13] Ibid: 96

[14] Ibid: 105

[15] ibid; 182.

One thought on “‘ …“second place” pretty much summed up how I felt about myself and my life – that it had been a near miss requiring just as much effort as victory but with that victory always and forever somehow denied me, by a force that I could only describe as the force of pre-eminence’. [1] A reflection on Rachel Cusk (2021) ‘Second Place’.”