‘Because Peadar loved to dance’.[1] ‘As if, having done the worst thing to each other, we could do no further harm, or any, really. And there was safety in that. Like the old world of my childhood. And, in this strange atmosphere, the shades of Peadar and my mother were somehow given a sort of life. A sort of permanent presence’[2] A reflection on the production of Blueberry Hill released online by Traverse Theatre Edinburgh for the festival, a wonderful realisation of Sebastian Barry (2017) On Blueberry Hill, London, Fishamble Plays / Faber & Faber (Directed by Jim Culleton starring Niall Buggy as ‘Christy’ & David Ganly as ‘PJ’).

Two men in a denuded landscape are waiting to know the ends to which their lives are tending. How did they get there and why? This isn’t by the way a description of Waiting for Godot and the landscape is at a notional level an interior one – although space and time relationships between the characters make the meaning of interior and exterior shift so that no measurable or stable setting is really viable to imagine. A denuded landscape or a bare interior can yield to various other scenes that exist, in words, sensations and feelings in a yet more remote interior – even something like an ‘inscape’ (a place and time so interior it is difficult to realise except as a ‘strange atmosphere’ potentially inhabited by ‘shades’, a bit like the Underworld visited by Odysseus.

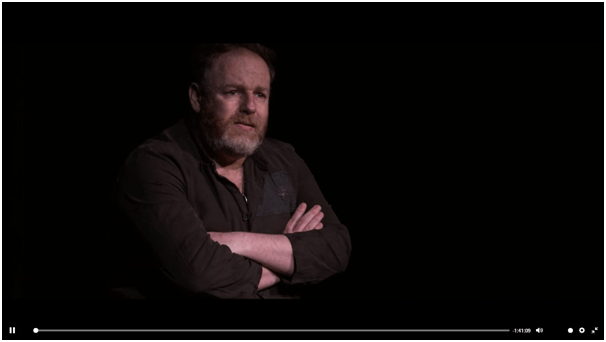

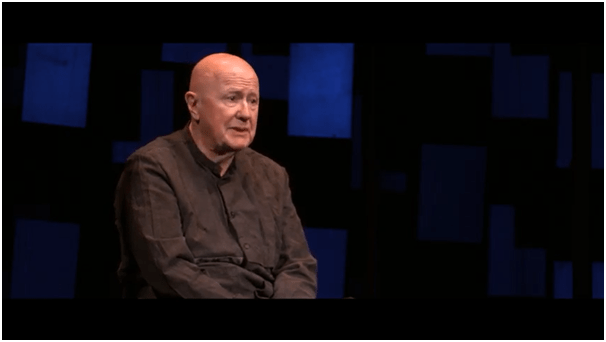

The play script tries to have it both ways, it describes a ‘cell, narrow and old’ but ‘pretty bare otherwise’ than for ‘a bunk bed’ but this production refuses to comply, even with the advice to the actors; ‘Direct address to us, but also, somewhat aware of each other’. For this production most of the play’s long soliloquies are addressed with each actor demonstrating unawareness of the other’s presence, utilising both stage spotlighting and a massive use of close-ups to isolate the character, with us as listeners – although we do not know quite why and how we listen to us or why we are addressed.

What lies behind the spotlight are shapes that will become even more unreal patterns of colour as the scene opens up to a wider vision. When, at that latter time the lighting opens up the stage, there is increasing awareness of the actors of each other and a shared space and time relationship.

I jump forward here though just to emphasise how before this stage in the play, soliloquy isolates the speaker with an audience recreating in words a space that is both imagined and remembered. It’s a necessity of the play that the cusp between an imagined scene and a remembered scene is blurred, since both mental functions share so many characteristics – where simple words like true, real and authentic lose their meaning or allow that meaning to shift uneasily between truths adjudged by different standards. Hence much in the story of this play is unclear and ambiguous and tests the authenticity as well as veracity of words.

This is true of the one the key remembrances of the text, PJ’s story of how he and a younger Maynooth trainee priest, Peadar, visited Inishmore in the Aran islands: ‘I have either two memories of it, or else as it happened two separate things happened simultaneously, which I know is not possible’.[3] But unless you allow the possibility that two things can be one thing in the emotional and even embodied lives of two males in isolation, nothing in the play’s handling of distortion is imaginable or memorable, except as an existential symbol, as in Waiting for Godot I think. And distortion in this play is a fact. Its truth depends on the fact that the way people evaluate what they see actuates changes in what is perceptible and known to perception.

A playwright is usually the authoritative arch-plotter of dramatic scenes in a text but in this play Barry delegates at least some of this function, as perhaps does Beckett to Godot, to that ‘fucker McAllister’. He is the unseen prison-officer who ensures that PJ and Christy are housed in the same cell; a man who lies to himself for his own amusement and fabricates scenarios whose endings he is amused to observe, note and comment upon. He can interpret their outcomes quite gratuitously, according to mood more than predestined purpose. This playwright-director is no Samuel Beckett because his own schemas of how to plan an encounter between persons are built in distortions from their originating motives to their eventual reflective conclusions; all we know is that:

… he seemed to get a great a great kick out of us, before he retired. Professional fulfilment, he called it. That he’d thrun us in together but we hadn’t killed each other. He just couldn’t get over it. Restored his faith in humanity, he said. Nearly got him sacked, more like. Lying fucker. But no, he said, no, it was a miracle. He was glad he done it.[4]

McAllister, when he set up the two men as cell-mates, also peppered the incident with distortions that effected the ability of each man to understand, if understanding were possible, or forgive each other. McAllister tells PJ Sullivan that Christy Dwyer stabbed PJ’s mother in the bath, naked, so that the insult to her was both two-fold and had a sexually voyeuristic edge. We know, because Christy tells the story of his murder of PJ’s mother in an earlier soliloquy that he stabbed her in the partial light of her bedroom as she was ‘walking across the room’ in ‘her nightie’.[5] That truth, once revealed to PJ at a later point ‘makes an enormous difference’ to PJ and begins the process of a reconfiguration of relationship between the two men who have each murdered the neared family member of the other.[6]

Manipulating people to see what happens is the stuff of drama but also of institutions; and not only prisons manipulate their inmates, residents or members. These real-life and dramatic manipulations rarely stop at those of spatial and temporal proxemics. They involve distortions of truth achieved by careful choice amongst options of how, and in what language people are asked to understand their relations to each other and sometimes by direct lies. There is an example of the former in the speech of Christy Dwyer’s of which I cited earlier an earlier part, where Christy goes on to tell of McAllister’s warning to him about PJ: “Now, Dwyer, don’t turn your back on your man, he’s a shirt-lifter”.[7] Is a gay priest the same as a homosexual cell-mate and are either the same as a ‘shirt-lifter’. Words matter and contain distortions within what to their speakers are truths. And this is an everyday event. Though Christy knows McAllister will not and has not the capacity to drive a long knife honed ‘to the thickness of a nail’, into his skull, that, given Christy’s history, ‘he shuts up with his homo talk’.

It is a moment of the queerest of queer liberations in my view. I sometimes fancy that the play was written anyway so that queer sons can imagine and enact within themselves the depth of their father’s love despite the struggles with which some fathers sometimes face in owning these sons as their own. There will be more of this speculation later. But so much of the play hinges around two scenes, one told by Christie Dwyer to the audience and another the same story as recounted to PJ and now again given to the audience as if it had not been heard before. The point in each case is to emphasise how deeply a father may love a son from whom he feels culturally estranged. So much of that estrangement lies of course in distorted ‘homo talk’. In PJ’s trial the court is told by the priests whom PJ told of his part in Peadar Dwyer’s death, wherein they had seen a mere accident, and would not otherwise be telling this story in public ,say, and this is the first we, as audience, have heard of this witness to sex from other versions of the story of Inishmore that they had ‘seen these fellas “at it”’: “The perversion that most offended God”, the judge called it’.[8] The language of the two priests, whose own reasons for visiting the Aran islands are undisclosed, use language that surely distorts the meaning, perhaps even the physical facts, which can be made out of a story of Peadar and PJ’s congress on the islands. This is even more the case when the judge brings the force not only of his legal but the state’s religious authority to bear on interpretations of the matter. It is so difficult to see love behind sex between an older and a younger man perhaps but it is their mutual love for the same man, Peadar, that brings PJ and Christy into some kind of union – symbolised by the most beautiful kind of ‘fast embrace’ in the play.[9]

Of course the irony here – possibly doubled by the lighting effects of this production – is that this ‘fast embrace’ is predictive of the two men’s mutual plan to ‘strike in the same instance’ as PJ aims ‘for my heart and I’ll aim for his’.[10] Never has the doubleness of meaning in men aiming each at each other’s heart – in love and violence both – been better dramatised. But we need to remember that love need not be discoursed differently whomever the partivipants. As Christy puts it so beautifully:

… I threw up, like a foolish child, and PJ is on his knees trying to mop up the puke, and alright, he comes over to me, and he puts an arm around my shoulder, and he says, “This won’t do, Christy,” he says, I mean, was that homo or what, yes, and I don’t fucking care if it was, I fucking love that fucking man, that fucking fucker PJ,…[11]

The return of the question ‘was that homo or not’ in this piece is the most beautiful of recognitions of the return of ‘homo talk’ to show the means by which the fundamental reality of what occurs becomes distorted in stories, talk and even single words. Reality is after all, queer, not normative in its construction, knowing nothing of the words naming a ‘perversion that most offended God’. This is most true when both men begin to realise that their fate lies in the fact, as Oscar Wilde says, that:

… all men kill the thing they love,

By all let this be heard,

Some do it with a bitter look,

Some with a flattering word,

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword![12]

And Oscar Wilde surely is part of the origins of this play which attempts to bring together, a bit like Fassbinder’s version of Genet’s Querelle of Brest, which utilises that lyric too, and of its queer wisdom. For this may be no surreal set like that of Waiting for Godot, and the intention is not solely to typify something basic about human existence and the imminence of lost and inapplicable value systems, but still attempts to show that love exists outside and at the heart of the most unlikely stories. Because it is unbelievable, isn’t it, that a man should learn of love from another man who has killed his son in an act of inexplicable self-preservation from otherness and who meets him because he has killed his mother, and the class privilege he believes to be supporting his son’s perversion. But that such ‘distorted’ and unrealisatic stories tell deeper truths is what we have always asked of literature, and this should be even more true of queer writing that refuses simplification and reductionism.

The defence or apology we need to make of Barry’s ‘invention’ as an artist is neither no more nor less than Sir Philip Sidney in sixteenth century England originally made for the Psalms of David in the Bible as an example of what artists actually do. If they distort is to be the ‘least liar’, the charge of lying through collusion no anti-queer judge or prison officer ever evaded.

For what else is the awaking his musical instruments; the often and free changing of persons; his notable prosopopoeias, when he maketh you, as it were, see God coming in His majesty; his telling of the beasts’ joyfulness, and hills leaping; but a heavenly poesy, wherein, almost, he sheweth himself a passionate lover of that unspeakable and everlasting beauty, to be seen by the eyes of the mind, only cleared by faith? …

…

Only the poet, disdaining to be tied to (…) subjection, lifted up with the vigour of his own invention, doth grow, in effect, into another nature; in making things either better than nature bringeth forth, or quite anew; forms such as never were in nature, as the heroes, demi-gods, Cyclops, chimeras, furies, and such like; so as he goeth hand in hand with Nature, not enclosed within the narrow warrant of her gifts, but freely ranging within the zodiac of his own wit. … (my italics)[13]

As Sir Philip Sidney says, the ‘least of liars’, as he calls the poet lives amongst those for whom lying is so primary it is not recognised as such because it is how the norm is constituted. And this is the world of The Ballad of Reading Gaol and the invented world of On Blueberry Hill. At the heart of the latter is the attempt to restore life to lost realities, particularly those of childhood and unconditional love, however much these realities may have faded into the background of an inauthentic society, where the objects of true feeling feel like ‘shades’. Let’s take for instance the story of Christy’s love for Peadar, his queer son.

Christy first tells this as part of the soliloquy that narrates his working life, experience as a emigrant, marriage (to Christine) and his delight in his children.

But Peadar, you see, was clever, I mean, he didn’t know a damn thing about anything, but he was book clever. … I mean he wasn’t like other boys in Monkstown farm. He didn’t want to go to see Finn Harps playing Bray wanderers at the football, … he wanted to go into town with me to see the fucking dried-out elephants and very dead snakes in the museum in Merrion Square., … And then it was the train to Connolly Station, … to where do you think? What hallowed spot of history or legend? Well? The shop where they sold clothes to the priests. …. …, where they sell such ravishing items of fashion.[14]

This ‘feminine’ and feminist sounding boy is as soft as a hot cross bun … soft, soft and wonderful’.[15] Not for nothing of course is the bun he is likened to itself a reminder of the passion of Christ for Peadar is, in a sense, an avatar of Christ, sacrificed even when “shining with beauty”.[16] But note too that when PJ retells Christy’s story about the trip to the dances at Dunedin Field, the martyrs of the boy who ‘loved to dance’ were queer men who died too in his name, sometimes by being made to ‘fall’ from a height of the self-oppressed loathing of another queer man (whose first thought about Peadar had been;’”Uh-ho, there’s trouble”. I didn’t know why I thought that’.[17]:

…Christy’d walk him over Dunedin Field to the dance hall, when he was bigger, because a lad like Peadar could be murdered on Dunedin field, even though he was from this side of Monkstown himself, there was a tree there in the centre of the field where a gay man had been hanged, as a matter of fact, now I think of it, there was a terrible hatred of what they called queers, and they knew Peadar was one of them, … .[18]

This play was written before the joyous last novels set in the States by Barry which celebrate queer love and diversity (for my log on the last of these follow the prior link). It is the last fling of a man who had known homophobia and was only beginning to put it into place as a result of his own son coming out to him. It is a beautiful and rich poetic testament. We expect that from Sebastian Barry but I hadn’t, before this, expected that the best mythopoeia of queer art would come from this defender, despite his friendship with Colm Tóibín, our greatest queer Irish novelist.

If you can see this play, do. If not, read it. It is brilliant.

All the best

Steve

[1] Barry (2017:52)

[2] ibid1:54

[3] PJ speaks. Barry (2017: 23)

[4] Christy speaks. Ibid: 56

[5] Ibid: 41

[6] Ibid: 53

[7] Ibid: 56

[8] Ibid: 37

[9] Ibid: 63

[10] Ibid:61

[11] Ibid: 60

[12] Oscar Wilde, Section VI, The Ballad of Reading Gaol Available at: https://poets.org/poem/ballad-reading-gaol

[13] From: Sir Philip Sidney (1891) a defence of poesie and poems. London, Paris, Melbourne, Cassell & Company. Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1962/1962-h/1962-h.htm

[14] Ibid: 28f.

[15] Ibid: 29

[16] Ibid; 17

[17] Ibid: 18

[18] Ibid: 51

One thought on “‘Because Peadar loved to dance’. A reflection on the production of Blueberry Hill released online by Traverse Theatre Edinburgh for the festival, a wonderful realisation of Sebastian Barry (2017) ‘On Blueberry Hill'(Directed by Jim Culleton starring Niall Buggy as ‘Christy’ & David Ganly as ‘PJ’).”