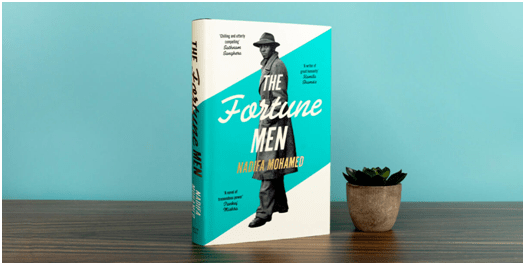

‘A. He doesn’t read me, and I doesn’t read myself. I doesn’t read or write’. What does it mean to re-create the unread in the fragments of really lived lives? A ‘reading’ of Nadifa Mohamed (2021) The Fortune Men Penguin Viking, Random House, London

The quotation in my title comes from the trial in court of its main character for murder, Mahmood Mattan. Mahmood is indeed a character in a novel and it is the function of the characters we find in a written story to be ‘read’ by others, by readers notably, as various meanings of the word in its formal definition suggest. Of course the quotation is meant to show the characteristic grammatical, and perhaps semantic, errors of a speaker whose primary language is not English and who is, it is emphasised throughout, lacking formal education. But, for me, this is a statement used with all the irony of which such a statement should be capable, especially in a text where the genre of the writing is, by necessity, unclear. For, as the review in The Guardian in May 2021 made clear this is the ‘real-life story of the Somali seaman who was wrongfully executed for murder in Wales’.[1]

But this is not a documentary recreation of events at all. Interviewed for the digital pan-African journal by Vicki Leigh, it is clear that not only did Mohamed read the various documents extant but that her own father knew Mahmood Hussein Mattan personally. I do not know therefore that of the various ‘(d)ifferent fragments of’ that man she found in genuine ‘police interviews, newspaper reports, medical files, and court transcripts’ that this one was from that documentary record. What we do know is that Mohamed, felt that only an imagined responses to those fragments that read him from within the space she herself inhabited would render him ‘whole’ The novelist must take on the duty of all fiction and faction writers of ‘stepping in myself and walking in his footsteps’.[2] It’s time then to see the man before we contemplate how Mohamed’s presence might have created from him the character we as reader of her novel ‘read’:

The photograph above shows the man in his full charm and comes from a retelling of the case by the Justice Gap website and is written by lawyer, Natalie Smith.[3] Of course the novel too tells a story of injustice and particularly of the massive effect in this case of overt bias of the British justice system (then but I think perhaps now too) against people whose skin is not white. In a clearly imagined incident Mohamed imagines Mahmood sitting in the prison’s ‘small bath’:

his body white apart from some flashes of his real skin – and asks himself what if he had been born with skin this white. He would have earned a quarter more as a sailor for a start, … . He might have become an educated man, …. He would know justice too.[4]

Michael Donkor, in an early review, appears to treat this kind of perception of bias and of white entitlement as part and parcel of the modern tradition of retellings of black history from a black perspective: ‘committed to correctively shining a light on recent British history’.[5] Examples would be, he says: ‘the Small Axe plays of Steve McQueen or Jay Bernard’s poetic retelling of the New Cross Fires in Surge (2019) – see link for my brief blog of latter. But, even of these artworks this is a reductive view of what art does and are too characteristic of how we see black artists from the viewpoint of the document rather than of literary art. What the piece I quote above does is play with metamorphic fantasies of its characters and author that go much further than just exposing bias and injustice. Mahmood is playing with the appearances so characteristic of art when it imagines alternative futures and realities, and in doing both character and author play the same game as literary fiction has done with the ‘outsider’ who tests the hegemonic values of the society that excludes him, such as the ‘salvage man’ in Spenser’s The Faerie Queene or Caliban in The Tempest, both of which test ideas about nature and nurture in the formation of character, with Spenser appearing more in the frame of the later type of the ‘noble savage’ than Shakespeare. Both are racist representations of slavery and its consequences but they highlight why Nadifa Mohamed might wish to revive the tradition to refocus how and why art holds responsibility for modelling the relationships between different communities and their values.

Now Donkor does pick up this literary figural type from the character of Mahmood calling the creation a ‘a shape-shifting character, variously positioned as a rakish antihero, plucky picaro, petty thief, charismatic dreamer, prideful gambler, doting father, anti-colonial firebrand and speaker of truth to power.’ I might have liked here more awareness though that these characterisation of Mahmood speaks of Mohamed’s artistic intelligence and wide literary knowledge. I think this matters because if it is the case that Mahmood ‘doesn’t read himself’, it is certainly not true that he isn’t read – a fact of the case that Mohamed emphasises by providing us at the end of the novel with a newspaper article from the time. For his defence in this report, Mr. T.E. Rhys-Roberts, called Mahmood; “this half-child of nature, a semi-civilised savage’. [6] Mohamed picks up these phrases in the novel.[7]

Moreover, Chris Philips in his documentary history of the case confirms the view that the highly educated Rhys-Roberts was literally attempting to ‘read’ Mahmood as ‘something like the traditional idea of the “noble savage’, but that this attempt in itself damned Mahmood in the ears of the much less literate jury who reacted only to the suggestion of Mahmood’s ‘savagery’ (as indeed anyone less educated in the traditions of the public school would know) as meaning ‘unrestrained violence and cruelty’: ‘It was a bad mistake and evidently it made a strong impression on those in court’.[8] That black men are read through lens painted with white prejudice is evident in the novel. It allowed the Cardiff police to produce witness statements that were stunning fabrications, yet it was to doubt only the reliability of Mattan’s witness that Rhys-Roberts spoke out, so convinced was he of the inadequacy of the mind of the ‘noble savage’. Mahmood is used to the idea that literacy feels like a war on the under-resourced, even when it is a purchased literacy, ‘from one of the scribes near the Public Works Office’ by his mother, who highlights stereotypes of sailors sojourning in the West to engage Mahmood’s supposed accrued wealth on behalf of his brothers.[9]

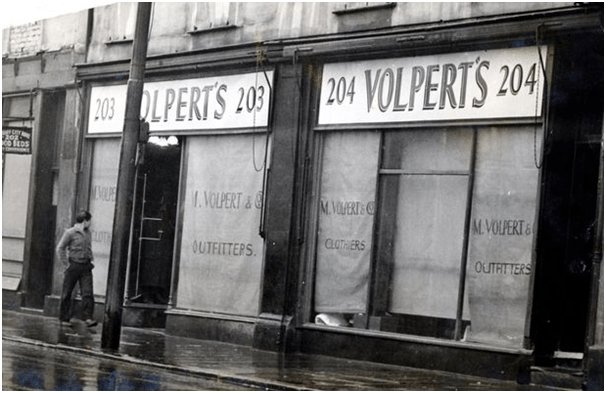

Stories can read ‘characters’ from life as well as reproduce, not the ‘character as such, but the reading of character. And it is the ubiquity of stories in culture – from those in communal gossip to written forms like newspapers and official reports that attempt to ‘objectify’ such readings. Trials in court often cause a contest in character reading and it is this which fascinates Mohamed here, but particularly the systematic suppression of the character of Mahmood as ‘read’ by himself. This is literally why he ‘doesn’t read myself’, at least not in public domains, where stereotypes remain king. This is revealed in a wonderful moment when the Jewish victim of the murder in the novel, Violet Volacki (based on the real murdered woman, Lily Volpert) is characterised by a Western Mail reporter as a hated ‘moneylender’.

Violet’s actuality as a real character, based on Lilly Volpert, is a fact known in multiple ways by different people (‘Even the seamen treated her with respect’). Her richness of self is defended from the anti-Semitic stereotype by Diana, her sister. Undaunted the reporter goes on to show that the entire cast of his version of Cardiff’s Tiger Bay is made up of people prone to his stereotypes:

“But there must be so many foreigners! Seamen from Bongo Bongo land and God knows where, violent men who are not used to our laws and the way things are done here.”

…

‘The police are looking for a Somali, aren’t they? ….[10]

And what the police (or indeed other institutional officials such as forensic medical staff) seek, which is a stereotype of this nature, the book shows us, they did and will continue to find by force of expectation, and story-building, based on such speculative material alone. And such expectations are built into stories, that claim authority, in the reading of racial type or character. The unctuous Detective Powell believes himself a well-read and educated man even if from different sources, used to interpret small facets of Mahmood’s story, than the Etonian Rhys-Richards.

… Powell collects his thought: Mattan is wilder than he expected, a real rogue with no respect for authority, a covetous darkie of no fixed abode. He’d read somewhere that for Somalis every man is his own master. They aren’t like the jovial kroo boys or anglicized West Indians, but are truculent and vicious, quick to draw a weapon and unrepentant after the fact. This one must have become bold after the soft sentences he’d received in the past; …[11]

Mahmood’s moral character stands at a distance from any such stereotype and this would show could he be heard in the hubbub of stereotypes which make, for instance, white men valorise but also marginalise the suspected hyper-sexuality of black men, like the man who true to persuade Mahmood to have sex with his wife whilst he watched.[12] They also cause even more kindly men to look at Mahmood’s bebhavious in relation to both eating and hygiene with prescripted expectations far from the truth of himself known to Mahmood.[13] Medical readings too depend on characterisations and racial types and feel they are not based on prejudice. For instance the forensic doctor is ‘looking up with his warm brown eyes’ (suggesting a kindness and assumed deference not elsewhere found by Mahmood, as he describes him in ‘objectifying’ officialese of court documents as: ‘A healthy negroid individual, active, in good health, with excellent teeth’. Zadie Smith’s White Teeth is a brilliant extrapolation of what lies under the bathetic finale of this sentence.

But even well-meaning reviews can repeat the fallacy. Donker is I think correct to suggest a literary genealogy to Mahmood as character type – the ‘picaro’, but may fail to see this as a device through which the author shows the nature of the mechanisms by which her character is moulded by others more than by herself. In another review in The Guardian by Ashish Ghadiali the reviewer goes the whole hog by describing Mahmood as a ‘lovable rogue’.[14] This may be the meaning of ‘picaro’ but it is not the whole of the character of Mahmood any more than Caliban’s attempts to live up to the monstrous typing he receives in The Tempest. There is danger in pursuit of the ‘lovable rogue’ stereotype to characterise black men who once breathed till a white state took that breath away as a ‘lovable rogue’ of deeply trivialising the injustice involved.

Mohamed takes her character’s multiplicity seriously; re-inventing him from within from his hopes, aspirations, deep emotions and complex selves combined, even down to the most wonderful of apocalyptic visions.[15] For what matters about Mahmood in my eyes is his role in bearing the vision of the ‘outsider’; bearing witness to a blindly privileged white society of the enormity of the abysses in its own take on reality – hence the apocalyptic visionary who sees Butetown as on the cusp of Judgement Day. In her interview with Vicki Leigh, Mohamed makes the point explicitly: ‘I think it’s a crucial part of my outlook on life, of being a perpetual outsider, of trying to work out all these things that are half-seen or half-understood’.[16] It may not be the most important facet of the character but my queer eye is forever open to the exposure of heteronormativity as the ‘normal’ that outsiders see through.

This is not to say that Mahmood is not represented as a great and awesome father to his children and husband to Laura but that, even that redeeming quality in her and many other eyes, is seen in a refracting lens of a complex psychosexual context, where we see things, like the notion of masculinity for instance, with a difference. Mahmood knows that white society is fascinated by his every dimension of the ‘outsider’. There is a moving moment where in an American institution Mahmood distances himself even from other Somalis, laughs at his transformation as a ‘savage’ and softens to a Mohawk boy from Canada, failing to be ‘real tough, hardening my eyes’ as he knows the male stereotype should be. Meanwhile the Germanic scientists continue measuring ‘every inch, and I mean every inch’ of both their bodies. It is a compelling moment in the study of masculine sexuality.[17]

This moment of revelation of something less than heteronormative, but not quite gay, is not alone in this novel and opens my eyes to the exquisite way that Mohamed explores outsider perspectives in ways that are nearly an intersectional treatment of her characters where variations against the norm are slight but important. It made me realise how and why it was important for Mohamed to recommend, amongst new Somali writers ‘wild stories and adventurers’ such as from the outside Mohamed Abdulkarim Ali’s Angry Queer Somali Boy’ as ‘high up on my reading list’.[18]

One of the major characters, but as ‘ghostly as Mahmood himself, is the sailor and bar-owner, Berlin. There is something intensely sexualised in the relationship between Mahmood and Berlin that never is sexual, and if so, is so in terms of the way each talks to the other about women whilst they enact flirtation: ‘he placed a hand over his heart, and with eyes dramatically lowered, announced, …. . This moment of near sailor ‘camp’ is followed by this reflection and generalisation of their mutual behaviour:

That’s how they met and how Mahood fell in love with Berlin. A love platonic and pure, for sure, but weighted by the close scrutiny the boy put the man under. His bearing, his ideas, his silences, his insults, his desires, his hates, … he memorized them and brought them home like birds caught in his snare.[19]

Men who gaze at each other begin to investigate their masculine identity not only behaviourally but emotionally, caught in the cusp between violent predation and identification by ingestion – a taking in of the other into oneself. Mohamed is too good a writer, for instance, not to notice that when she describes the mutual gaze that determines a judgement that the other is ‘attractive’, she makes it difficult for us to know whether the prose refers to Mahmood looking at Berlin or the other way round:

Berlin is standing fixed behind the bar, his arms stretched out either side of him, hands clenching the counter, his head bowed. Lost in this revelry, it takes him a moment to notice Mahmood settling into the bar stool in front of him; he finally lifts his head and his distant-seeming hazel eyes settle ambivalently on him. His face is reminiscent of a shark’s – a hammerhead – with his flat skull and wide, dark lips. He is handsome but in a dangerous, bloodless way. He never loses himself or allows people to lose themselves in him. Mahmood knows that he abandoned a daughter in New Yorek and a son in Borama; he speaks of them easily, but with no guilt or regret. He likes this lack of emotion from Berlin. It means you can tell him anything, and it is like speaking to a wall: no shock, no moralizing, no pity or disgust.[20]

The sensualised but emotionless face of the older man adapts itself into the features of the younger man in this passage as the reader struggles over the ‘he’ that is exactly referred to midway in the passage. The ‘bloodless’ mutual appreciation by men of each other’s looks is hard to escape here, just as the extra signification in the description of ‘dark lips’ hovers between the sensual and the violently sinister. This wash of desire over her characters is even referred to darkly by Mohamed in her interview with Vicki Leigh when she denies that she ‘decided’ to write Mahmood’s story but it was a kind of ‘desire, a feeling that it was a story I couldn’t shake’. Amongst which were elements of fascinated desire lies an attempt to come to terms with her own past and displaced family: ‘ …, Tiger Bay, the world of immigrant men in the 1950s’.

She knows that understanding this story also involves the understanding of why, in this world, violence lies so proximate to desire in male solidarities. And the need to understand is urgent, particularly when much of masculine mutual desire and the narcissistic identifications this involves, becomes entrapped in social stereotypes of black men, perhaps even those they encourage in each other. It is not enough to ‘look away from the imperfections, if not abuses, of our societies until they pose a problem for ourselves’; they are already a problem the moment they are noticed.[21] For close scrutiny of the outsider is a confrontation, just as Camus and Frantz Fanon would say with ‘the rebels that have always pushed against the way things have always been done, who tried to create space for new ways of living’. The alternative to rebellion is the enclosure into madness and an asylum of the Jamaican character, who probably killed Violet, Tahir Gass; who without hope looks for ‘friendship from Mahmood’ but has been ruined by being raped by Italian soldiers in the War.[22] The contradictions for Gass are unsustainable and instead of rebelling he kills silently. It is a kind of craziness Mahmood rejects even to escape execution, because this is how white privilege gets its ‘victory’.[23]

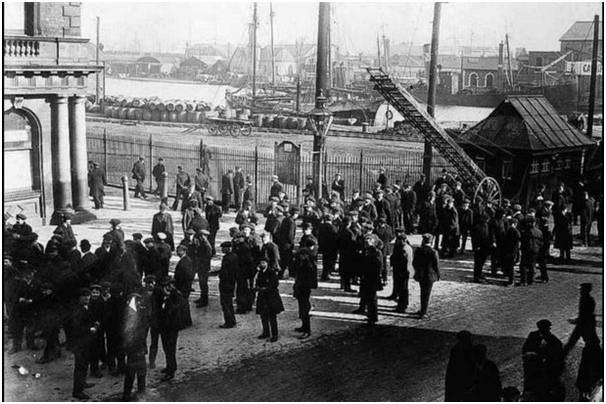

And there are important moments when men, both black and white, could have engaged with a common oppression that has made them the kind of men they are. On such scene is in the ‘Labour Exchange’wherein: ‘Out-of-work miners, dockworkers, drivers, handymen, barrel boys, plumbers and factory workers mill around, their eyes avoiding each other’.[24] At these moments men do not see but sense each other as dangerous competition rather than as persons. Mohamed has Mahmood compare this scene himself to the prison spaces in which men ‘associate’. When men steal looks at each other, the surge of ‘testosterone’ it motivates is used for aggression rather than any mutual appreciation of each other. They ‘size each uo’ for a fight rather than for recognition of attraction to each other’s person; ‘An awkward smile on his face as men size him up, testosterone charging their glances with electricity’. But there is no hint of Walt Whitman’s ‘body electric’ here as between Berlin and Mahmood, rather embarrassment at facing each other’s untouchability. [25]

There is so much here that is difficult to articulate and that can be overstated. However, what can’t be overstated is the degree to which Mahmood, a well known man in Butetown to this day, sees his home – Butetown, Tiger Bay and the docks as the home of working class potential gone wrong and, which though it looks like a hellish inferno might spout a new life and land: ‘an eerie and bewitching site that catches his breath every time; he half expects an island or volcano to spit out from that bubbling, hissing stretch of petrol-streaked water, but it always cools and returns to its morose, dark uniformity by morning’.[26] And the ambivalence of Tiger Bay is what sparks the apocalyptic dream when Mahmood is in prison. For most of us, there are the myths of the plucky lives that Tiger Bay brought forth but Mohamed makes these lives anew – finding in them a queer intersectionality that threatens to ‘tear the walls down’. One of my favourite pieces is Berlin’s talk about the encouragement he gave to the very real figure from Tiger Bay, Shirley Bassey. Let’s enjoy it again as a means of ending these comments:

“I had a half-caste (sic.) girl come to the café to sing, dressed like a boy in a baker’s hat, straight up and down like a boy too, but she sings like she wants to tear the walls down.”

“What’s her name?”

“Bassey, Shirley Bassey. She made good money that night, her hat full to the brim. Her father was that Nigerian that got into trouble with the little girl, but she’s doing well enough without him”.[27]

So lightly does the novel bear this kind of historical cross-referencing, we may forget the transgressive aspects of the Shirley Bassey who is introduced to us here, redeeming the faults of fathers who err. That’s a pity! The James Bond films have a lot to answer for.

This is a tremendous novel. Don’t Go Away until you have read it.

All the best

Steve

[1]Michael Donkor, Fri 28 May 2021 09.00 BST Available at: :https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/may/28/the-fortune-men-by-nadifa-mohamed-review-injustice-exposed

[2] Vicki Leigh ‘Interview With Nadifa Mohamed – Acclaimed Author of The Fortune Men’ in June 28, 2021. Available in: https://pan-african.net/interview-with-nadifa-mohamed-acclaimed-author-of-the-fortune-men/

[3] Natalie Smith (2018) ‘Long Read, Miscarriages of Justice: Killed by injustice: the legacy of Mahmoud Mattan’ In The Justice Gap( (27 September 2018 | 7:53. Available at: https://www.thejusticegap.com/killed-by-injustice-the-legacy-of-mahmoud-mattan/

[4] Mohamed (2021:335)

[5] Donkor, op.cit.

[6] Mohamed op.cit.:367

[7] Ibid: 294

[8] Philips, C. (2020: 193) Hanged for the Word If: The murder of Lily Volpert and the execution of Mahmood Hussein Mattan London, Chris Philips. Available from: https://www.lulu.com/en/gb/shop/chris-phillips/hanged-for-the-word-if/paperback/product-jjjrjr.html?page=1&pageSize=4

[9] Mohamed op. cit.:37f.

[10] Ibid: 99

[11] Ibid: 105

[12] Ibid: 119

[13] Ibidid: 335

[14]Ashish Ghadiali (2021) ‘The Fortune Men by Nadifa Mohamed review – a miscarriage of justice revisited’ in The Guardian (Tue 25 May 2021 07.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/may/25/the-fortune-men-by-nadifa-mohamed-review-a-miscarriage-of-justice-revisited

[15] Mohamed op.cit.: 353

[16] Vicki Leigh op.cit.

[17] Mohamed op.cit.: 35

[18] Vicki Leigh, op. cit. On her recommendation I am awaiting delivery of this important intersectional memoir of displacent, racism, diaspora and injustice.

[19] Mohamed op.cit: 179

[20] Ibid: 27

[21] Vicki Leigh, op.cit.

[22] Mohammed op.cit.: 2, 8 respectively

[23] Ibid: 247

[24] Ibid: 20f.

[25] Ibid: 197

[26] Ibid: 5

[27] Ibid: 193

One thought on “BOOKER SHORTLIST: ‘A. He doesn’t read me, and I doesn’t read myself. I doesn’t read or write’. What does it mean to re-create the unread in the fragments of really lived lives? A ‘reading’ of Nadifa Mohamed (2021) ‘The Fortune Men’.”