A reprint of Virginia Woolf’s essay in the book accompanying the exhibition Challenging Convention: Gwen John, Laura Knight, Vanessa Bell & Dod Proctor says, of the paintings by the writer’s sister, with regard to what these pictures tell you about their artist: ‘Their reticence is inviolable’. Even about the subjects she chooses to paint Woolf says ‘what has Mrs Bell got to say about it? Nothing’. [1] Does the stress on the silence of paintings matter when the painters are women rather than men? And, if so, why? Reflecting on the Newcastle-upon-Tyne Laing Gallery’s 2021 exhibition, dedicated to Amy Barker.

One of the most beautiful things in the book published to commemorate this exhibition is the wording of the standard letter that went, and several times, to the distinguished galleries and institutions holding paintings by one or more of the group exhibited: Gwen John, Laura Knight, Vanessa Bell & Dod Proctor. We are told the wording was originally by Amy Barker. I had the privilege of paying to attend a Curator talk of Amy’s before her sudden death and I recorded it in a blog: the blog is available from this link. It must tell us such a lot about Amy that the gallery still attribute the brilliance and nuance of the original idea for this exhibition to her, even in the dedication of the exhibition publication (‘In memory of Amy Barker’).[2]

But of Amy’s presence itself we will find, at this distance only faint reflection. But of silent talented women there are tales that need telling, even when they themselves choose not to; or no longer are able to. And such tales are plentiful in this exhibition and its publication. For instance the quotation from the artist cited to head the section on Gwen John is amazingly apt: ‘I may never have anything to express, except this desire for a more interior life’.[3] Another cited quotation in the book from the artist’s papers enumerates rules ‘to keep the world away’, that ends with:

Have as little intercourse with people as possible; When (sic.) you come into contact with people, talk as little as possible …[4]

Now much is written in feminist history of how women’s voices are not only marginalised but sometimes silenced in social history, and the history of the great cultural institutions meant to voice the views of people generally, sometimes even those of whole nations. Sometimes female silence is contrasted with, and perhaps, it is sometimes suggested by some, caused by the loud (and perhaps otherwise empty) clarion of self-advertisement that masculine self-presentation sometimes seems to be. Take Michael Holroyd’s Radio 3 talk on his new Augustus John (Gwen’s brother) biography:

As his pictures grew bigger and emptier and more unfinished, hers had diminished into nervous jottings until finally they vanished. But in their prime their work had subtly complemented each other’s, in such a way that knowledge of one can lead to greater understanding of the other.[5]

But that would be to over-estimate both the power of stereotypes over all women (and relationships between specific men and specific women). In art history the tendency to make these poorly nuanced simplifications is legion, although never in the Amy Barker talk I heard. You will find these simplifications prefaced by talk of the ubiquity of the ‘male gaze’ (from a concept in the critical film theorist Laura Mulvey) in art, whereby images of women are produced for male consumption by men. There is an example of this in the book from this exhibition by Ella Nixon, a PhD student at the Laing, in this exhibition’s booklet of Dod Proctor’s wonderful painting of 1925, Girl in Blue, from the Laing’s own collection. We are asked to see the way we look at this picture and its subject as unsettled, but unsettled by an inversion of the male gaze in which tropes used by male painters – such as Picasso’s ‘neo-classical monumental’ female nudes – are, by virtue of their ‘female authorship’ shattered: it ‘shatters the traditional power dynamic embedded within the notion of the male gaze’. [6]

The account goes to say that ‘Proctor’s depiction … is borne out of sympathy rather than the perspective of male desire’.[7] This appears to happen merely because we know the artist is a woman and therefore, are we to presume, not likely to see this young working-class girl as a sexual object. There are so many assumptions here that I find incredibly had to swallow, particularly given Proctor’s deliberate choice of a first-name that was not immediately identifiable as that of a woman. Another cause of this inversion into a female gaze rather than a male one, we are told, is the style of both the clothing of the subject (and the colour tonality of the painting as a whole) which is soft and liminal in a way that quietens desire: ‘used by Proctor not to suggest a sexually available woman but to present an emotionally complex moment of private contemplation’.[8] We understand the silence suggested here as a kind of binary opposite of brash male loudness compared to feminine softness. But the statement itself fails really to evidence how and why the subject is claimed to be non-sexualised. It uses binaries of sex/gender associatively but without any critical justification I can see. Indeed, in my view it returns the notion of the female gaze to a thing that is non-discriminating and empty of content, other than the supposed preference for empathic emotion over sexual object desire.

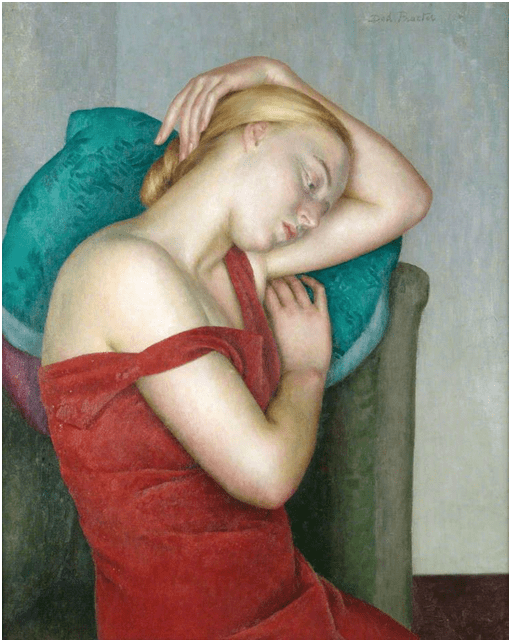

Even if that assumption can be made – and surely it cannot always be made, since otherwise a queer perspective would be impossible which it is not in art or anywhere else – then it reduces the painting to an observational desert. In Girl in Blue the social status of the young working-class girl model, Cissie Barnes, is signified by the actual function of aspects of her clothing. If that were not the case this painting could be seen as exactly the same as paintings of the decidedly middle-class and educated model otherwise used by Proctor, we know as Eileen Mayo, also a painter. In paintings of Mayo, eradicating a ‘male gaze’ seems barely attempted; indeed it such gaze may be invited by the trope of the slipped shoulder band (which got John Sargent into trouble in painting Madame X, even though he did not go as far as dressing Madame X in scarlet).

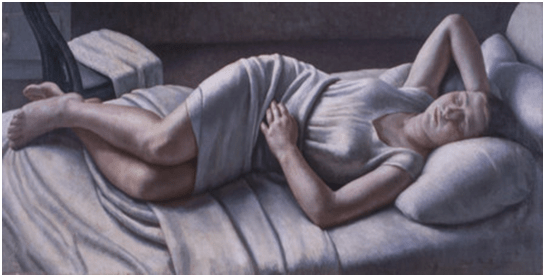

This exhibition is saved because such assumptive and intellectually thin readings aren’t in the majority in the exhibition book. So much about the use of Cissie Barnes as a model in particular speaks of Proctor’s intelligence about female diversity rather than presenting women in the stereotyped position of a victim of patriarchy alone. For instance the more famous works Morning, Early Morning (the smaller version that appears at this exhibition) and the photograph from (which Proctor worked from in 1926 (the latter is reproduced in the book of the exhibition) precisely emphasise Barnes’ vulnerability to Apollo and to the seduction of, and by, the world of bourgeois art. Whilst not saying as much the account Charlotte Higgins gives of Early Morning when it appeared in a Pallant House exhibition is much less assuming about how and why women depict women and how they represent vulnerability to male gaze:

… Morning (1926) shows a woman, asleep and perhaps on the verge of waking, with her right arm thrown back over her head. George Eliot’s description of the Vatican Ariadne, in Middlemarch, might also serve to describe Procter’s subject: “She lies in the marble voluptuousness of her beauty, the drapery folding around her with a petal-like ease and tenderness.” Well, not marble: paint. But even so, the white sheets and nightgown that Procter has arranged around her model strongly recall the pale chilliness of antique sculpture. View the image in a certain way and you could almost feel that the stony solidity of those sheets was consuming the young woman, like some heroine from Ovid’s Metamorphoses being steadily transformed into a rocky outcrop. But despite the cool density of that cotton drapery, the figure is a sensuous being, fleshy and pink, and her left fingers – departing from the original pose – hover suggestively around her crotch, … . The sitter for Procter’s painting was Cissie Barnes, the 16-year-old daughter of a Newlyn fisherman, and there’s ordinariness here: she’s very definitely not a mythical heroine, even if we’re being reminded of her Renaissance and classical forebears.[9]

Ella Nixon’s contribution reminds me more of the tedium of versions of art history that call themselves feminist without quite ever honouring women or femininity in any way, other than through stereotypes one might hope feminism might confine one day to history. However, I think reflection on silence and the silenced with regard to women can be nuanced as is in the writing and art of women artists in this exhibition. The book of the exhibition is rather thin on original works of history or criticism but is excellent in providing copies or prints of original documentation. We could regard Virginia Woolf’s review of her sister’s art as exhibited from February 4th to 8th 1930 as one such piece, although it is disheartening that the printing contains spelling and grammatical errors that seem particularly inappropriate in Woolf’s wonderful prose. Woolf explains the choice of silence as a reflex of the very nature of visual composition, as the truth of its particular kind of visual language. How would such an artist, who happens also to be a woman, address women, starting with her ‘self’, as a theme, topic and style. It would not be in the ‘wordy’ way that is so inevitably used by a novelist.

But Mrs. Bell says nothing. Mrs. Bell is as silent as the grave. Her pictures do not betray her. Their reticence is inviolable. That is why they intrigue and draw us on; that is why, if it be true that they yield their full meaning only to those who can tunnel their way behind the canvas into masses and passages and relations and values of which we know nothing – if it be true that she is a painter’s painter–still her pictures claim us and make us stop. They give us an emotion. They offer a puzzle.

And the puzzle is that while Mrs. Bell’s pictures are immensely expressive, their expressiveness has no truck with words. Her vision excites a strong emotion and yet when we have dramatised it or poeticised it or translated it into all the blues and greens, and fines and exquisites and subtles of our vocabulary the picture itself escapes.[10] [Of her ‘painting of the Foundling Hospital’ also worked upon by Hogarth, Thackeray and Dickens] it is dust and ashes – but what has Mrs Bell got to say about it? Nothing.[11]

The continual harping on the name ‘Mrs Bell’ may be an intentional effect reminding readers that Vanessa’s husband and father of her sons (but not her daughter), on paper at least, was Clive Bell. Mr. Bell, of course, says far from ‘Nothing’ about the subject of art and artists. Indeed it is his popularisation of art as ‘significant form’ that is surely referred to in this passage’s characterisation of how artists themselves see art, yielding its: ‘full meaning only to those who can tunnel their way behind the canvas into masses and passages and relations and values of which we know nothing.’ Who is this ‘we’ who, not only claim to, but actually know, just as they say, ‘nothing’? Clearly all the exemplars are men who have a lot to say. Can this not be a silent reference to women who keep their peace amidst male chatter using exclusive aesthetic codes (‘fines, ‘exquisites’ and ‘subtles’). It could equally be that Woolf creates a distance here between Vanessa Bell and the greater Bloomsbury critic of the visual arts, Roger Fry.

Woolf, rather than seeing Bell diminished by silence about paintings, makes her appear the more powerful – as enduring, for instance, as the grave. Whilst talkative, great men and institutions – like Foundling Hospitals – are putatively reducible to physical ‘dust and ashes’, the silence female interiority on the other hand goes on drawing us in, as the best art should. There may be a disturbing collusion here with another binary gender stereotype, but it acts to empower women to make us see the world differently and as something that endures the temporal world . This world is dominated by male talk about the world rather than experience of it: ‘this strange painters’ world in which mortality does not enter, and psychology is held at bay, and there are no words’.

I suppose I want to say that a truer take on this exhibition will not be through approaching it as the return into our busy world of strong but repressed female voices but of a challenge to the patriarchal presumptions of voice as our main agency in life and a preference for something more transformative. And the exhibition addresses this from the very reception piece of the exhibition, where Bell’s The Tub stands as the price of entry. There are very few paintings that so strongly create a silent world where what we feel matters more than that which we see. So much so that the codes and signs of a real world are made impossible and subverted: such that all perspective is sacrificed to the design of shape and form and masses on a flat surface. We cannot enter this scene because it is entirely flattened out: the tub, precariously standing on the vertical surface of it, as if upended. We can only enter it through the subjective self of the nude model, whose downward interior gaze rejects our eyes and makes them incapable of merely ogling her body.

That this exhibition defies crude reduction of women artists to their biology alone, or even a voice, is the real achievement. Rather the exhibition champions coded mood. That is clear from the opening where a selection of all four exhibited painters hang on walls painted white especially for the exhibition, although white is also the (suitable) wall colour for Gwen John. From then on, each artist is represented by the colour of the walls on which the pictures hang. I do not sense anything reductive here – the choice of ‘pink’, the most easily reducible to a code with a single meaning is allocated to the most complexly interior of these women, Vanessa Bell. Everything works well in this silently brilliant curation, from the placing of apt citation for instance in relation to the relative design of the placing of pictures to the contrasts of complex colour internal to a picture (never have I seen so strongly the effect on Vanessa Bell of the example of Matisse – in her 1915 painting of her husband’s mistress, Mrs St. John Hutchinson, for instance, than I have in this great exhibition). I refer to that painting in an earlier blog (see link). See for instance the placing – so fortuitous – of the painting of a Charleston interior in which Duncan Grant so carelessly but lovingly sits, in the photograph – made by the exhibition’s publicists themselves for Twitter – below.

Of course the surprise find for most people in the exhibition is Dod Proctor and I am really grateful to now know that fascinating painter. I find myself fascinated in part of her objectifications and realisations of bourgeois senses of the otherness of the working class, in the case of Cissie Barnes (about which I make hints above) and black Caribbean child subjects, such as Gabriel in St. Lucia painted between 1950 and 1960. The text captions for the paintings tell of a controversy based on the fact that Proctor paid these models in sweets only and therefore can be conceived to have exploited them. However, there is more of a problem here than that. There is an appropriation of the black boy child in the interests of validating the emotions he raises in mainly white viewers, a kind of naturalised acceptance of the poverty of the colonial subjects by transforming them into icons of basic emotions, as sadness in the case of Gabriel.

If I had to say which artist moved me most, it would be Gwen John. Strangely the choice of an extract in the exhibition from an old thriller novel was as appropriate a prompt to my interest as I might have found. The thriller is unknown to me and is named The Gwen John Sculpture: A Tim Simpson Mystery by John Malcolm, written in 1985 and published by William Collins & Sons. Chapters 5 and 6 are reproduced in the exhibition book, I think in part. Whilst admiring the paintings’ depiction of ‘muted calm … apparently restrained passions’, Simpson contrasts this with ‘Rodin’s lovers embraced in a cool, eternal marble Kiss, symbol of his erotic passion and inspiration, some of which spilled dramatically into this Welsh lady’s life’.[12] One might expect a man in the 1980s to equate the binary between extremes of quiet and very much louder ‘passion’ with stereotypical gender assumptions, but I think we might guess that the power of passion in the relationship John had with Rodin may have come from this surprisingly contained woman (at least the woman we ‘see’ in the paintings). Those paintings, as Woolf says of Bell’s pictures, are ‘immensely expressive’, though ‘their expressiveness has no truck with words’. This is as true of the portraits as of her characteristic ‘interiors’, which seem interior in more than one way. The famous A Corner of the Artist’s Room from 1907 – 1909 conveys emotion from the absence of the female subject betrayed by the cast off parasol and dress and which are in dialogue perhaps with bolder expressionists such as Edvard Munch, Paula Modersohn-Becker and the poet Rainer Maria Rilke. Compare its self-conscious suppression, for instance, with Modersohn-Becker’s Portrait of Lee Hoetger with a Flower. The same interest in women who feel abandoned by life is there but the important factor in John is the silencing of the colourfully emotive.

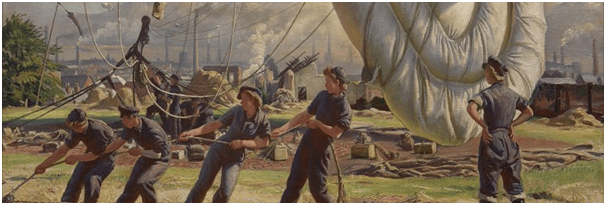

But I had a greater surprise. I originally went to this exhibition to accompany friends who have a great passion for the work of Laura Knight. It is not a passion I shared and, for me, the real revelation of the exhibition was my ability to connect to a figure I have (through prejudice mainly) associated with a rather grim and oppressive hierarchy of British art: a reputation of one who deliberately shut themselves off (as I thought) from innovations in painting and, instead, jealously guarded the conventional embodied in established institutions. I had known some of her work as a war-artist but before seeing it ‘in the flesh’ thought it merely very good Establishment propaganda. Of course A Balloon Site: Coventry, of which you see a detail below, is that, but seen in the right size, the industrial landscape comes through and painting seems semantically, as in other ways, richer.

But I like it not just because Knight loves to put women in commanding poses usually reserved for men in that period but because of what seems to me to be her fascination with the very cusp of the portrayal of the margins where gender and power mix in images that convey her admitted (according to her biographer Barbara Morden) interest in art and androgyny.[13] For me that speaks out from her very subtle self-portraits but even in the very aggressively male appearance (or so it seems till you look closely) of The Gypsy from 1939. The design and semantics of this picture depends on the blending of the floral motifs (from the bed head behind the man and his silk scarf) and an expression that is either aggressively threatening or extremely vulnerable. The more I looked; the more the latter came through. Now the biographer Morden has very little truck with those who see in Knights’ statements, such as that about her friendship with Dod Proctor, as potential material for the exhibition of a ‘definite queer sensibility’.[14] Indeed at another point she says plainly, of Laura’s excited attraction to a woman who her husband thought wrongly might be his lover, Ella Naper;

There were overtly lesbian artists in Newlyn, Hannah Gluckstein (known as ‘Gluck’) for one and Joan Coulsen …. But Laura Knight was not one of them. … Whether from this (referring to the nude paintings of Ella by both Harold and Laura Knight) we can imply sexual interest or obsession in either of them would be unreasonable and presumptuous…[15]

Queer people are used to such reductivism: if it isn’t ‘overt’, it is rude or presumptuous to ever query the general presumption of heterosexuality unless more directly encoded. In fact ‘queer sensibility’ is not a matter of the presumption of homosexual feelings, open or latent, but of ways in which the norms of heterosexual coupling as they exist ideologically, are opened up to query in any way that begins to challenge them. One can forgive Morden her defence of Laura Knight, although the very thought that defence is needed is of course oppressive, but not the way in which it seems always okay for people who claim not to have felt a need to challenge heteronormativity to presume what does and what doesn’t in the complex and hard to classify in human relationship and interaction. And even the jewel of the Laing’s Laura Knight collection, A Dark Pool ,is surely an expression of something very hard to classify by norms of any kind. So much passion is implied in the creation of the rocks over which the woman clad in orange stands through a very obvious use of layered impasto paint, that we feel the woman’s attraction to the unseen ‘dark pool’ as a threat of self-extinction, a kind of possibly fatal risk to take. Anything like an illusion of a relatively flat surface in the representation of the sea is lost and the cusp between rocks and sea – into which she looks – disturbs because nothing in the painting helps us to avoid the suggestion that the sea is literally slipping downwards into a chasm. This is presumably the ‘dark pool’ of the title. The young woman’s orange dress is lifted from behind by the wind but that wind is also an impulsion in the picture for her leaping (or being pushed) into that void. The very unstable placing of her naked feet on the slippery rocks further implies the instability that is the dynamism of the image – the sensation of falling into or between the cracks between rock and sea and other rocks.

Of course you may feel none of that. I was not expecting – to but feel it I did, just as I felt the potential ambiguity of her circus and low-life paintings. When Laura Johnson, as she was, was hoping to make her name as a young artist in the Staithes colony of art she missed out of her portrayals of the period the help she received from women artists in the colony whom were, at the time, more celebrated than she, such as Hannah Hoyland and Isa Jobling.[16] Yet Jobling’s painting contains motifs of similar or more pointed portentous concern with the future (the prospects) of women and not just middle class women. In the case of A Staithes Fishergirl seated looking out to sea, the painting seems to me to reflects the two statements Rosamund Jordan, a historian of the Staithes group, says and links them:

Professional life was hard for serious Victorian women artists. … when women artists married, their wifely role was expected to take over their profession and they tended to become mistresses of the flower study. Isa Jobling’s talent was immense and her paintings of working people cannot be bettered by any of the Staithes group.[17]

It is clear that Laura Knight’s feelings about power in relation to women and herself were not straightforward in the facts of her omissions of important women who were in fact her mentors.

So see this exhibition while you can. For me it is another reason to love the friends who were the cause of us visiting and who also, incidentally, bought us a beautiful meal from a restaurant selling the cuisine of Kerala in Southern India. Was that paradise?

All the best

Steve

[1] From Virginia Woolf’s1930 essay on her sister Vanessa Bell, cited with grammar and spelling mistakes (here corrected) in Gráinne Sweeney (ed.) (2021: 41) Picture Article: Meet the Artists: Challenging Convention London, Artizine Limited. Pages 40 – 43.

[2] Gráinne Sweeney (ed.) (2021: 55) Picture Article: Meet the Artists: Challenging Convention London, Artizine Limited

[3] Cited ibid: 14

[4] Cited ibid: 19

[5] Michael Holroyd (2004) ‘Mirror image: Driven by shared demons, Gwen and Augustus John complemented each other, writes Michael Holroyd’. A Radio 3 talk in The Guardian (online) Sat 4 Sep 2004 01.19 BST Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2004/sep/04/art

[6] This is not to say that, unlike the case of Ella Nixon which I go on to explore, analysis of how a function such as could have been described as the ‘male gaze’ (always a presumption nevertheless) cannot be subverted technically or by play with the mediating pragmatics of a scene in comparison with say recognised versions of the phenomenon in, for instance, Titian and Renoir. For instance it is brilliantly done in an analysis of the 1911 Laura Knight painting Daughters of the Sun by Barbara Morden (2021:115f.- revised paperback edition) Laura Knight: A Life Carmarthen, McNidder & Grace.

[7] Ella Nixon (2021: 48) ‘Girl in Blue’ in Gráinne Sweeney [2021] ed.) op.cit.

[8] Ibid: 48

[9]Charlotte Higgins (2016) ‘Waking the gods: how the classical world cast its spell over British art

Dod Procter’s painting of a girl on the brink of waking echoes an ancient statue of Ariadne – and is just one example of a post-war revival in classical imagery’ in The Guardian (online) Fri 21 Oct 2016 12.00 BST Last modified on Thu 22 Feb 2018 17.10 GMT. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/oct/21/waking-the-gods-how-the-classical-world-cast-its-spell-over-british-art

[10] From Virginia Woolf’s1930 essay on her sister Vanessa Bell, cited with grammar and spelling mistakes (here corrected) in Gráinne Sweeney (ed.) (2021: 41) Picture Article: Meet the Artists: Challenging Convention London, Artizine Limited. Pages 40 – 43.

[11] From Virginia Woolf’s 1930 essay on her sister Vanessa Bell, cited with grammar and spelling mistakes (here corrected) in Gráinne Sweeney (ed.) (2021: 41) op.cit.

[12] Cited ibid: 20

[13] Morden, B.C. (2021: 118f.) op.cit.

[14] Ibid: 113

[15] Ibid: 133

[16] Ibid: 66f.

[17] Rosamund Jordan (2003: 38f.) Staithes Group Centenary Exhibition (October 2003) York, Tom & Rosamund Jordan / Simon Wood.

5 thoughts on “‘Their reticence is inviolable’. ‘(W)hat has [she] got to say about it? Nothing’. [1] Does the stress on the silence of paintings matter when the painters are women rather than men? And, if so, why? Reflecting on the Newcastle-upon-Tyne Laing Gallery’s 2021 exhibition, dedicated to Amy Barker.”