‘In this darkness, words were foolish things’. [1] A novel that reflects on words unsaid and/or unsayable in some past queer lives. Jonathan Lee’s (2021) The Great Mistake London, Granta Publications.

Jonathan Lee is a British writer who now lives in New York. How did we lose him and why? When he was interviewed by Mariella Frostrup following the publication of his novel High Dive (for the BBC Radio show Open Book), Frostrup says in her run up to the interview how little we know about Jonathan Lee in the public domain and mourns the lack of ‘biographical context’ before declaring to Jonathan her intention that he might ‘divulge more about’ his ‘mysterious life.’ Intention or not, Jonathan Lee reveals very little other than the biographical context for his knowledge of the Grand Hotel in Brighton, where High Dive is set in order to tell the story of the bomb, planted by the IRA Provisional’s, which almost killed Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

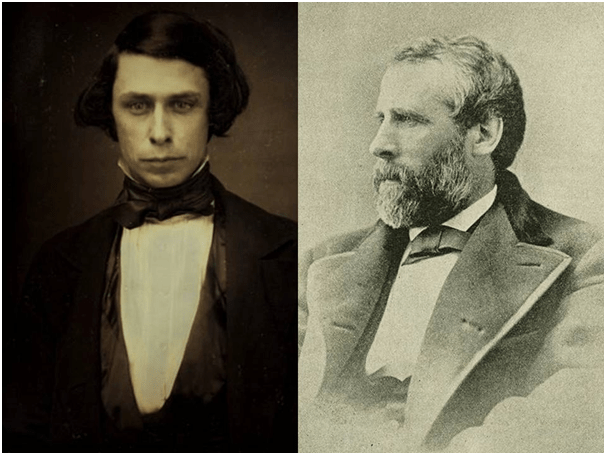

How much more will any reader want to ask about this novel, which is again about a ‘real’ character’ from history like Thatcher who was at the receiving end, this time successfully, of assignation or murder. In this case the violent death is the more frustrating a focus because, as Detective Inspector McClusky discovers, the murder was entirely based on a case of mistaken identity: ‘Murder by mistake was an ironic end for a man of such set intentions’.[2] Perhaps lives, and some deaths, need to be seen as the product of random events and unnoticed incidents where no-one’s intentions are fulfilled – not properly at least. In recreating this life and death, Lee tells us from the very start that Andrew Haswell Green (the focal person of this novel, started life as ‘invisible then as he is today, in twenty-first-century New York’. Re-finding this character’s model then was to unearth him, ‘through cracks in the accounts, the spaces between death sentences, the pauses in obituaries’ in order to give him ‘light and air to grow’.[3]

Andrew Haswell Green attracted Lee as a novelist seeking a subject I believe, given the persistence of this theme in the novel when his life motives are recounted, because Green rather liked things not to be left in a mess, without ‘light and air’ being let into their presence. As a boy Green had, according to Lee:

A tendency to impose order on his brothers’ mud-caked boots, left there by the door in such dirty disarray, a mess he hated to look upon, that he felt an urge to solve, lining them up by size and type at night, …[4]

This was a fine motive for the man who made Central Park in New York possible – a venture we see in process as the novel progresses from flashbacks to the past, returning continually to the serial unfolding of the present. Yet as Green dies we contemplate not the orderly end of a series of events but, ‘a rare sprawl of coincidences and missteps and mistakes, a measure of bad luck and a degree of design …’.[5] This is not the kind of ‘mess’ that the fastidious Green could have wanted from a death, after a life so purposeful – or apparently purposeful.

So this is a novel about a man with a ‘mysterious life’ by a novelist who appears to have a life of the same order, with events deliberately secreted by darkness and silence. And maybe that is all we should need as readers looking for ‘biographical context’. We have to take the life, as it is lived or not lived, on the terms limited by a whole set of agencies of which few are in Green’s control. And hence the novel is based on the fact that ‘mistakes’ often lie at the root of events. It is all the more poignant then that the novel ends with a recreated memory of Green’s trip to the underground foundations of New York where in darkness and silence (that place beyond words) he suddenly realises that there might be no ‘false moves’ or mistaken intentions:

He was here with Samuel. Their hands again were almost touching. He felt light-headed, a fraction drunk. His pulse seemed to quicken and fade with the sound of spades and within his own veins the blood felt sluggish but sure, as if, down here, there was no such thing as a false move.[6]

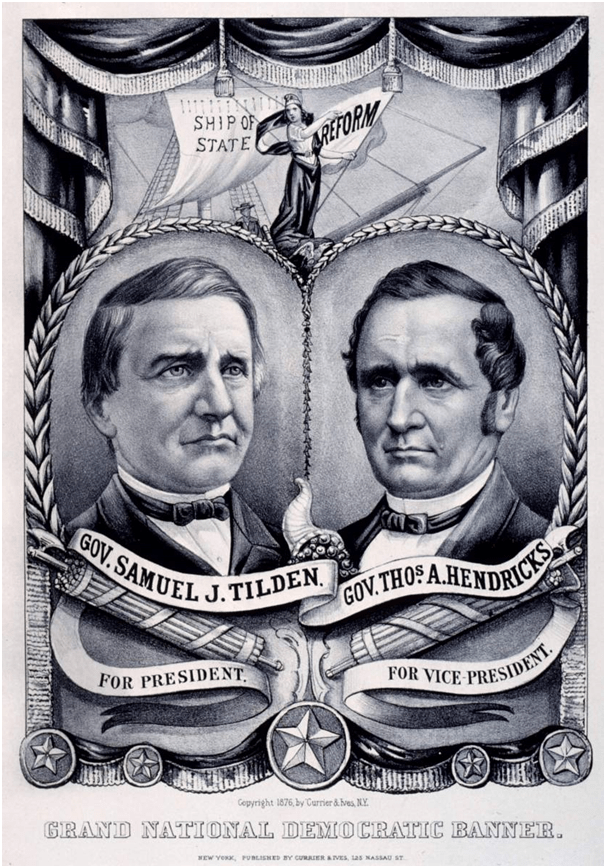

This dark, silent place beyond words is where Green, for the first time, feels his lifeblood flowing and no longer held back. And it concentrates on ‘Samuel’. However, in so allusive a play with fact and fiction, we should not mistake this ‘Samuel’ to be merely a representation of Samuel Tilden, the historical figure with whom no-one knows whether or not Green had a fulfilled sexual and/or romantic relationship. The novel plays games with this idea, of course, as in the opening of Chapter 26: ‘He was in bed with Samuel’. This event is not what a modern reader might think and expect of a novel, whose central character is clearly drawn as queer, however unfulfilled. The men are fully dressed in bed and pretend to each other, that they are where they are as a matter of pure convenience, given they were ‘working late together on a speech or a public project, or an idea that seemed too intimate to discuss within range of strangers’. [7] Lee is often described as a stylist. You have to realise what games are being played between notions of the ‘public’ on the one hand, and the ‘intimate’ on the other to realise how much these ironic sentences serve meanings that remain entirely subterranean and unspoken.

Novels have been written before about how the marginalisation and censorship of love between men plays out in damaged relationships and even more short-circuited interior lives, but never (if we except Henry James) where elegance of style has served as an index of that repression. After all elegance of style nearly always is an index of repression, however beautiful in itself. The important thing about this subtle novel is that ‘Samuel’ in the novel is never just a representation of the historical Democratic Party politician and Presidential candidate, Samuel Tilden. Indeed the name ‘Samuel’ becomes both for us and Green a signifier of relationship with a man that might be both loving and sexually charged. That underground scene in the final chapter is prefigured in a scene where Green visits the cellar with a young man in his employ (‘Samuel’ of course) to find a means of defusing a home-made bomb that has been sent to him in an attempt at political assassination. This young man unearths nameless anxiety in Green: ‘He was lonely without being able to admit he was lonely. He was melancholy without feeling he had an excuse to be melancholy’.[8] And this Samuel recalls yet another, Samuel Allen, who appears to have first excited Green to sexual romance, by ‘straddling’ him in a boyhood fight. Most queer men remember such a scene without prompting as revelatory and life-predicting:

Sam’s shirt was unbuttoned now, partway, his chest, that bone, its hard name – clavicle? – and Andrew now felt a strange burst of joy in his heart, a blood rush that had been absent these last few years … .

Straddling Sam Allen, holding his friend’s wrists to the dirt, he looked with unblinking green eyes in that thick handsome face, and he though, Disgust or desire? In what proportions was Sam, in this moment, experiencing these adjoining feelings? Andrew couldn’t see, he didn’t know, because his spectacles had fallen off his face.

Where were the spectacles? For a moment he did not care. He was full of the excitement that thrives in the seconds before rejection or acceptance are announced.[9]

In such a primal scene ‘rejection or acceptance’ are wider emotions that they might appear – they are a measure of accepting and rejecting the self that one could be without the pressure of repression, censorship and marginalisation of queer feelings. It is the same scenario repressed beneath the cellar visit to an underground and the final scene of potential love beneath the streets of New York.

These moments are rare in the queer novel and it was at this point that I felt the same hunger for ‘biographical context’ mentioned by Mariella Frostrup. How does Jonathan Lee know all this and communicate it in such a coded way. Yet my desire to think that Lee might be a queer writer is surely immature, even in a 66 year old. Queer sexuality is not a matter of identity but of writing that plunges beneath the norms into speechless situations that pre-existed discourses about homosexuality. Jonathan Lee need make no personal confession – to demand that of him is to misunderstand how sexuality is divided by heteronormativity and not by nature. In that final Underground scene we are told that, in its ‘speechlessness’ and darkness there is an ‘escape from his own daylit life’ where he ‘only cared that he was not alone’.[10]

Green’s sexuality remains fluid because unspoken and unexpressed and as much about an existential problem that might dictate we might not be really healthy when we are ‘alone’ because there is no other alternative. Green’s need for love and acceptance resonates with the many ways in which Green faces the limits of mere masculine self-display. If, as he father thinks, he does not grip an ax (sic.) like a man would, writes with a ‘womanly hand’ or embraces the feminised thought to be embodied in a dislike of the world being untidy and messy and a wish for elegance.[11] Green’s world as written in Lee’s fine and innovative prose is a world where the mere manly is part of the mess from which he wishes to escape. The play throughout with dirt and mess is part not only of the neat tidiness and fastidious cleanliness of the man but of a refusal of gendered identities, like that of his father, deficient in the ‘tools of empathy’.[12] His talent lies in ‘making cluttered spaces clean, at removing mess’.[13]

Look at this troubling but wonderful passage. It intrigues me and concerns Green’s obsessive walking between Protestant churches and his obsessive gaze on ‘city gentlemen’:

Their phrases, gestures. An opportunity to watch and imitate, which had to be the first stage of possession? In the rearmost pews his lips moved in mimicry. Performance. And sometimes desire. … . He … wondered if his own occasional doubts about the existence of God might in some way be mutual. Did anyone in the heavens really believe in him, Andrew Green, this awkward boy below, his spirit, his potential for good? His own question frightened him into muteness, the kind of silence the living rarely know, the moon hanging sullied by smoke in the sky, filthy with the expulsions of men.

What exactly is happening in this paragraph as Green measures himself against ‘city gentleman’ as a stage in their possession or possession of their attributes. And how is this confuted with desire? And how does the combination of possession and desire also fit with the fear of an ‘awkward boy’ in growing into a man. Because men are associated with the pollution of an industrial city. But there is also something even more of concern in the dirtiness he sees in men, who stain the sky and the constant moon making it ‘filthy with the expulsions of men’. That is a strange phrase ‘expulsions of men’. I sense here a subterranean fear of male ejaculation – of the signs of sexual maturity which green otherwise cloaks in silence. Of course, the reading of this by others will possibly, and even probably, differ. I find this prose so suggestive of the repressed though not only here but elsewhere. The problematic world of heteronormativity is continually that which is to be feared.

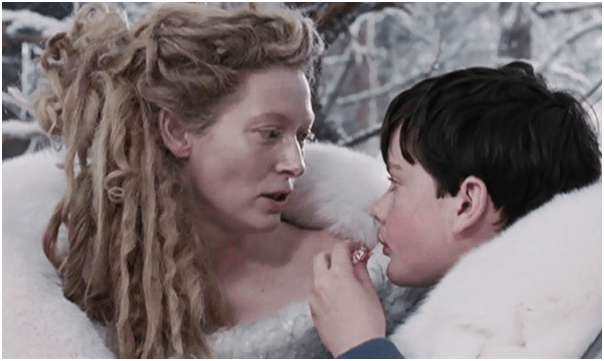

There are moments of unspoken disgust in the novel. When Sam Allen rejects him for instance, it is with disgust.[14] The ’accidental’ sexual contact, though fleeting and based on mistaken identity yet again, between him and the overseer of slaves, Mr Carlson, hides both the disgust and desire of both men.[15] The only union with Samuel Tilden, other than that he in fact possibly imagines in the final chapter, is a very cold affair indeed, where both men take on the qualities of a Snow Queens:

In his perfect, sentimental vision he and Samuel would be bundled in furs, sledding, snapping the whip and feeling the horses go faster, the two of them drawn through the thrill of the snow, the air freezing their faces along with their sense of selves. Utter whiteness. Birds in blue sky. The energy of friendship, of union, in land protected and repaired by all that snow. He had a strange idea that if they could make themselves sufficiently cold, become men entirely of ice, everything else between them would have to break or thaw. …[16]

This vision of ‘union’ under the conditions of a sexuality totally frozen so that what can flow flows somewhere else than in their fantasy is quite brutally clear in its attempt to capture how the silenced world of love between men might have been imagined by a man like Andrew Haswell Green, a man who does not know how to want what he knows he would love were a man to offer it openly and with acceptance of self and other in his heart.

I think this novel is remarkable. It is the first novel by Jonathan Lee I have read. It will not be the last.

All the best

Steve

[1] Jonathan Lee (2021: 289).

[2] Ibid: 268

[3] Ibid: 9

[4] Ibid: 9

[5] Ibid: 8

[6] Ibid: 288

[7] Ibid: 222

[8] Ibid: 64

[9] Ibid: 25

[10] Ibid: 288

[11] Ibid: 12, 264, 15.

[12] Ibid: 29

[13] Ibid: 47

[14] Ibid: 26

[15] Ibid: 151

[16] Ibid: 226