‘It was then that Adrian [Ryan] told me of his regular, sexual trinity involving Johnny [Minton] and Lucian [Freud] in the latter’s St. John’s Wood “squalor” located in Abercorn Place, NW1.’ [1] Even if it ‘frightened the bejasus out of’ the two bisexual men,[2] Minton’s life and work momentarily triumphs over theirs in this exhibition where themes of secreted enclosure between art and life meet Minton’s openness, however tragic (in the end) to Minton himself. A reflection on the Unholy Trinity: Freud, Minton, Ryan exhibition currently at Bath.

I have really enjoyed breaking every rule of academic art history practice in this piece. It is just a frank celebration of the triumph of queer art and ‘subjective’ is hardly sufficient to describe its boldness of interpretation. But in life there has to be a little fun. I hope some queer friends (and maybe some others not so self-interpreting, will enjoy it. So here goes….

This exhibition is based on a sexual triangle involving three painters that was, in all probability, relatively short-lived. When Julian Minchin wrote his biography, Adrian Ryan: Rather a Rum Life in 2009, all he would say about is that Ryan had met Freud ‘in the nightlife of the Chelsea pubs and, with John Minton, enjoyed a relaxed and easy intimacy which outlasted the duration of the war’.[3] In this exhibition that cosy picture is painted (in words of course) rather differently as an ‘unholy trinity’. The rather extreme adjective ‘unholy’ fits very well for the name Freud gave his abode where the three met regularly for sex: his ‘squalor’. I get defensive by this kind of choice of words which rather estranges the relationship(s) involved in this threesome and fails to get to us its roots in why the attachment had the length it had. This is particularly the case in that Freud was to go to great lengths to suppress the kind of information that began to get out to Minchin and others. Relatively happy to be known for his Spartan ideas of loyalty to his lovers, his later mythical self representation required that they not be complicated by the kind of accusations of being queer like himself from Francis Bacon, who claimed that he only fathered so many children from so many women to hide that fact.

The relationship with Bacon went the same sad way as with Adrian Ryan – both being dropped not only from any chance of future contact and from his personal history, except as Freud himself latterly wanted it written. Minchin says that it was not a triangle of equal bonds between the three – Mark Brown in the Guardian review of this show reports Machin thus:

“It is more of an isosceles triangle,” said Machin, with Minton seeing the relationship through a casual sex lens. Freud and Ryan experienced so much feeling that “it frightened the bejesus out of them,” he said. “What they had, they just couldn’t accept it. But I think what they had was something so precious”.[4]

There is no admission of this ‘precious’ element in the catalogue as in the interview based on it by Brown, although we will continually see the relationship as most important in the lives of the bisexual men, both of whom had multiple relationships with women (Ryan had 3 wives but none of these constituted his most important relationship with a woman), had had children and had almost to rule treated women in their lives badly with Ryan often revisiting his liking for young men in affairs within his marriages. His second wife, Joan, felt his marriages broke on the rock of his ‘inability to be loyal, because he liked men’; though, it appears that Joan had also been attracted to Adrian’s first wife, Barbara.[5] Of Freud’s feelings about either loving or, more simply, sex with men, there is sparse evidence though his painting can speak volumes to some of us. Whatever, the issue, it is clear that Minchin gives more credence to the emotional lives of these bisexual men than he does to Johnny Minton, who is said to be involved mainly for sex and/or as a replay of his complex triangular relationship with that most infamous of post-war gay couples – ‘The Two Roberts’: The name given to the ubiquitous togetherness of the Scottish painters (and socialist nationalists) Robert MacBryde and Robert Colquhoun.

As I examined this exhibition I began to feel that it was Minton who comes across as the most interesting painter, despite any claim to assess the relative significance of the three. Of course Freud is less well represented at this exhibition than in other places. Only one of the works here is one that is usually included even amongst his early best works (that being Girl with Roses 1947-8 – use the link to see it). Although these works clearly demonstrate that he was the most skilful in drawing figures and in setting an overall consistency of mood in his designs – if you like that kind of thing – they are not the masterpieces of his whole oeuvre to which the Tate is offering another insight to in Liverpool at the end of this year (I’m already booked to see this in September). But there is a connection between Freud and Ryan as artists that cannot be applied in the same way to Minton either. Each of the former artists shows a fascination with what is dark and hidden in the human psyche – something that lives behind the wide eyes of early Freud figures and in the existential isolation they often illustrate. In Ryan this extends to a preference to abandoning the figure altogether, of which Machin writes brilliantly in his earlier biography, and the positing of an almost existential isolation.,, where the world is seen robbed entirely of population except secreted behind the doors and blind windows of the houses of a Cornish (or other) landscape, as in Dawn over Newlyn.

Ryan’s home (Myrtle Cottage) is, according to the title this picture has in this exhibition (Dawn over Newlyn, View from Myrtle Cottage) the source of the viewpoint on Newlyn but the perspective feels to me rather impossibly mixed. There are confusions over where, between hills and the valley on the valley’s right, backed by a mountain, the distant vanishing points might lie. Moreover, these seem to be contradicted by an almost dynamic aerial downward perspective on roofs and dark passages (as if from a roving bird’s eye, hidden between rows of these. These homes appear first, at the base of the picture frame in linear series running alongside hidden streets and then in muddle as the ground rises unevenly behind these streets.

The light of the rising dawn from the east, reflecting on roofs that appear wet from night rain, emphasises the darkness of those west-facing windows that almost meet the viewer’s gaze. There is a felt absence of population and of the motion that we associate with the living figure. It is a most beautiful painting (perhaps my favourite of Ryan’s) but it celebrates and extends a moment of stasis rather welcomes the change the dawn predicts into a living day of lively human activity it perhaps ought to betoken, a holding back from the lives inside those homes and indeed any other overt interiority. I sense that in Freud’s brilliance at opaque figuration too, although the hidden or concealed interiors are of a different sort. Machin puts it, of Ryan, in 2009 thus:

What you never find is his getting past the exterior. His own homes are no exception to this rule. … there are no interior views, despite his interest in objects and furniture. There is in Adrian a place beyond which one does not get.[6]

Machin develops this point by looking at the few paintings which do include a figure (nearly always ones set in France not in Britain). But it is always a sole and lonely figure he shows us – alone within the observation of this secretive artist. Machin says, in a brilliant sentence, that this constitutes ‘a system for projection; a closing in n himself while using others as illustration’.[7] Western art is in love with artists who both secrete emotion and project it into images that are uncertain in their meaning or intention, a tendency it equates with nuance, but which is also clearly associated with our civilisation’s love-affair with repression and of only partial fulfillment. It is some such judgement that might have encouraged Mark Brown in his review to say of the three painters that, ‘Freud is head and shoulders the star’.[8] I would even dare to say that it is a taste for masterly reserve in painting that sets so high a standard of greatness on the whole work of Lucian Freud in our present estimations and, on the whole I am inclined to accept that evaluation for myself too.

However, it is a strange aesthetic when one comes to think about it in a world that also includes Walt Whitman as an artist and the latter is a better model for Minton than Ryan or Freud. I think of Freud human figures too strangely when I see the vey many paintings Ryan did of sea-creatures, but of fish in particular. Here are two from this exhibition:

These are ‘still lives’ – more appropriately known in French as the painting of Nature Mortes (dead nature) – and it is this genre that otherwise Ryan rejoiced. However, his love of painting fish was noted by friends as an oddity. Eardley Knollys, one of the Sichel Boys (see my blog) but an art dealer too of some importance, was also clearly in love with Ryan but couldn’t help disliking the fact that he could make a ‘fine painting … of some hateful rotting skate’.[9] Yet to dead fish, Ryan returned again and again for a subject. Late in life, and after his diagnosis of cancer, he enjoyed being the subject of a themed art exhibition at Sutton house called ‘A Kettle of Fish’ and wrote for it a piece he entitled Why I Paint Fish; the whole short text of which is quoted by Machin in his biography. It is the dead apparent unchanging nature of fish that attracts him, although their reputation, once dead, for extremely smelly decay hardly backs up that idea.

When times change, the landscape changes and the urban scene changes, and the fashions and appearances of people change, but the fish remain the same. The same as the Romans painted at Pompeii, as the Dutch….. .[10]

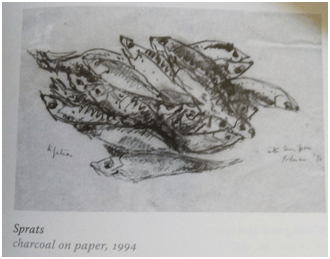

You have to remember here that the lack of change to which Ryan points is not even in the flesh and look of once-living fish themselves (live or dead) but in their role as a model for the artist’s subject or content. But even then, Machin in 2009 finds that Ryan may have been expressing some of his deepest reserves of withdrawn humanity. Even the least of his fish pictures, even a plate of mussels, expresses something that goes quite deep into The Ryan Minchin first exposed in his biography. There is always a group of animals and there is always some separation that isolates one of the group from the rest. In Three Fish, it is the animal at the top of the picture, whose eye catches ours and transfixes it, unlike the deadness of the rest of the group. Some mussel shells are separate from the rest. Likewise in a charcoal drawing on paper reproduced in the 2009 book, Sprats, Minchin finds a theme:

The tangle of fishes – bought for Adrian from Sainsbury’s for little more than a pound – against the translucent off-white paper is dramatic, … as though they were still moving . One stands out from the crowd, the nearest one to the viewer, the remotest one to the rest and the least abstracted and tangled up. “He was in the group and yet he wasn’t” – the astuteness of Guy Roddon comes again to mind,[11]

Whether Ryan or I am fanciful here is a matter of interpretation and of willingness to see how deep some personal themes might go into the very idiosyncratic iconology of a painter like Ryan. Nevertheless, this feeling of alienation from the groups in which he was thought to be a part seems characteristic of the man Minchin knew and the biographer gives a range of evidence for these groups whether they be the modernist innovators of Newlyn and St. Yves, or the fishing community of Mousehole. Both groups, and Ryan himself, kept guard of important cultural differences even down to the names given to fishing boats that made them appear separate entities. Ryan insisted they were ‘prams’, the important and undoubted members of the community, whose naming practices he was mimicking, begged to differ.[12]

When we consider the ‘unholy trinity’ Minchin has unearthed, both Ryan and Freud maintained later silence on the matter but Freud more than Ryan. One wonderful part of the exhibition I saw at the Victoria Gallery Bath has a video replaying part of an interview with the painter David Tindle by Minchin filmed by Isaac Biglioli in February 2020. In it Tindle confirms his knowledge of the ‘trinity’ and including the role played by Johnny Minton, ever on the lookout for queer friends. Tindle confirms he is told Minton that he was not queer and that Lucian had said that he ‘would be the first to know it if true’. Freud was to denigrate anyone adding to this evidence and Minchin shows how, without the facilitation of Minton, Ryan too felt unable to assert a relationship to Freud and let it ‘diffuse’.[13] What is left of the ‘unholy trinity’ given that the answer to ‘when shall [these] three meet again’ was, after Minton’s suicide, The Raven’s ‘Nevermore’.

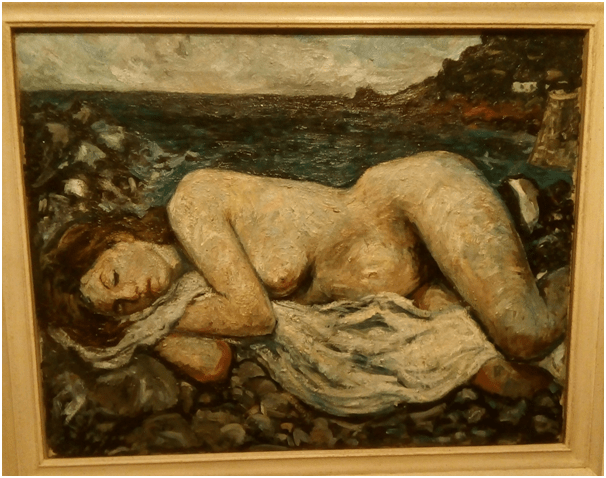

I think there is a commonality between Ryan and Freud, though the latter’s ambiguity about his early queer encounters had a lot to do with the fact that it was okay as a Companion Of Honour holding the Order of Merit to have a reputation for fathering 35 children with different women but not to have confirmed that he had sex with men.[14] For Ryan the relative silence had more to do with a sense of the nuance locked in private lives. For me, it speaks in those closed-in townscapes described by Minchin and his preference for the pinched almost close as in his picture of Mousehole Harbour Quay. His one female nude (in this exhibition and a beautiful painting) feels to me to act as a front to his passion for the sea, which appears about to take her in her sleep. Minchin senses that Ryan was ‘terrified of female power’ because of his inability to account for his masculine ‘side’ in any simple and satisfied way – it is always being questioned by women whom ‘he either idealised or disliked’.[15] And this nude is either being consumed from behind or has taken over the world of men at sea in its entirety and is threatening to overshadow it.

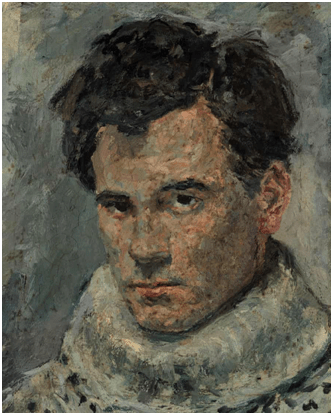

All I really want to illustrate is that the queerness is only ever only addressed from an angle in painters like Ryan and Freud, what at some level embrace the secrecy enforced up it by an oppressive society. And art likes such nuanced play with the emotions. What I loved about this exhibition is to discover just how radically and openly queer Minton’s art is in contrast to the other two. There is a sense in which he, unlike the other two, was not playing the role of the lovely young man who rather enjoys being the cynosure of a desiring male gaze. If we look at the cheeky and most beautiful self-portrait in this exhibition we know why he was longed for, as a very young man, by Sir William Brass, who seduced him.[16] Was it fascinating to be seen by Clement Freud (whose openness about his own bisexuality came as a surprise to me who remember the lugubrious celebrity of the man from my childhood) as ‘the most fanciable of the beautiful people in Soho’.[17]

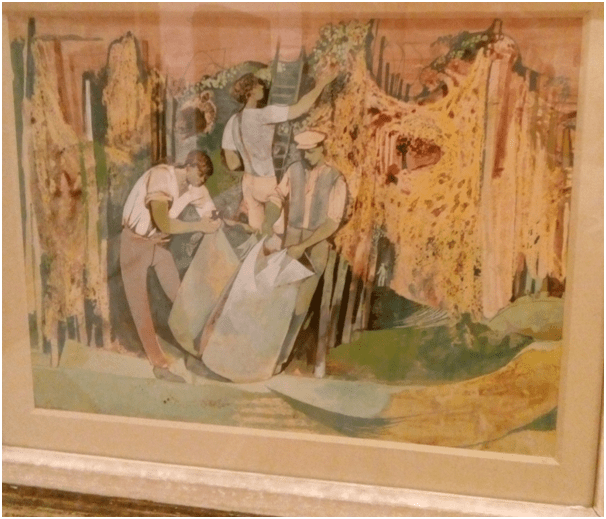

Minton in contrast was just queer, if often neurotic (as David Tindle says in the video). He painted his queer self and its projections. I came out of this exhibition rejoicing in this artist, whom I have ever liked but not seen paintings of in the flesh in such quantity, because of this obviousness. Mark Brown’s review does not even attempt to laud Minton. He writes: ‘Minton is probably best known as an illustrator and the tragedy of a life he took in 1957’.[18] That’s not much to say about anyone. Yet there are some remarkable pictures here that speak of projections of queer desire that are open and honest, and many of my own favourites that are obviously not great paintings but icons of the appreciation of male beauty in male yes, such as the lovely Neo-Romantic piece, The Hop Pickers of 1945.

And then there are those wondrous narrative paintings, not least Jamaican Village of 1951 (use the link to see Christie’s wonderful reproduction of the painting), which seems to tell the story of queer interactions (from distant longing to coming together after search to isolation) and issues over an almost epic scan, even down to the sleeping or dying man in the bottom right of the picture frame, in which some see a projection of Johnny’s suicide. But the surprise painting to me was The Death of Nelson (a pastiche of the great Victorian narrative painting in the ‘Great Men’ Carlyle tradition by Daniel Maclise), which having seen previously only in reproduction, failed then to impress. But the basic premise of this painting is the analogy between a theatrical stage and a ship’s deck. This is even more emphatically pronounced by the deliberateness of not creating an illusion of perspective for this scene. The deck is almost vertical and feels ready to lose its contents into the pit of the viewer’s vision, such that to look is to feel as if we must hold the images lest they fall. Seeing the original emphasises that the main action is deliberately described by a kind of spotlight in which the dying Nelson of popular myth implores Hardy’s kiss. But the scene is stolen not by these Maclise pastiche figures but the adoring (if also dead and dying) sailors who still adhere with difficulty to the lower picture frame on both left and right. I have travestied this in the following collage:

The content here is not so much a pastiche of Daniel Maclise’s painting but of Minton’s own fascination with the physical body of sailors as images that combine the allure of naked desire with the embarrassment of a society that has so thoroughly marginalised that desire as to render it acceptable only in dead and dying bodies. For me, this is a political statement that might have applied too to Ryan, who also attempted suicide in order to resolve his bisexuality and its tribulations (at least in my interpretation).[19] It is a way of taking the embarrassment that swam around the myth of Nelson’s death and that last desired kiss (if it was indeed that which was said) and animating it so that the lives of queer men are honoured and ennobled by images of beauty in death. It is a complex moment but oppression derives such complexity from life.

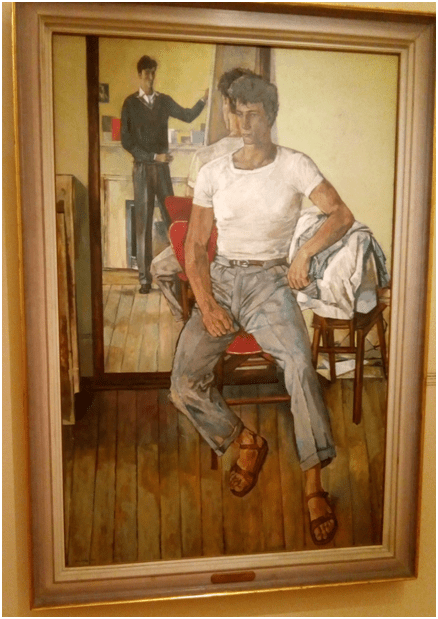

If I like Minton’s openness it is not an openness either without nuance. The difference between it and the other two men is that they use reserve and secretion as the royal road to that nuance, This openness can be emphasised by a brief look at my two favourite pictures of Minton in the exhibition, the full length portraits of Kevin Maybury, whom Francis Spalding describes in her biography of the painter as ‘a good-looking, predominantly gay Australian who was working as a carpenter at the Royal Court’.[20] Kevin’s role in stage work is ichnographically exploited, using some of the same destabilising effects we see in the Death of Nelson, especially the vertical stage setting. Spalding’s analysis of the painting I know best that features at Bath cannot be bettered, showing Kevin’s almost futile attempts to regulate the effect on him of Minton’s flamboyant attention with his ‘collapsible ruler’, ‘saw and T-square at his feet’.[21] But the larger painting of Kevin at the exhibition I did not know. Here is my photograph of it:

In this painting, Minton refreshed the tradition of painter and model motifs for a queer audience. There are the same destabilizing illusions but not as prominent here, with more concentration on the mirror world into which the self-portrait of Minton draws Kevin where touch is continually enacted but only ever illusory. Even the opposing slant of the floor boards helps to create a kind of illusion of proximity at a distance, where Kevin’s clenched hand provides a kind of sexualised dynamism, and the pastiche contraposto positioning of the feet give body to what seems flat in the visible working of the artist’s lighter gentler hands. Kevin nevertheless seems poised to fall forward, to break the distance necessitated by the form. It is a lovely painting about both love of the body and the person. It is decidedly and frankly queer, and for me is a queer version of the Pygmalion effect and so brilliantly analysed by Victor Stoichita which play out the ‘opposition between the (“interested”) creation of the work and its (“disinterested”) reception; the allusion of the erotic charge implied by and in its creation … and finally the ironic thematization of forbidden touch’.[22]

This is a painting inviting the queer touch, almost like a caress it moulds the offer of Kevin’s body to the painter who pretends to stand away from it. This is the very stuff of art, but it is openly frankly queer here. I love it. There is nothing of touch in Adrian Ryan’s Mousehole female nude, everything in the promise lying lightly on the felt folds of Kevin’s clothing that are particularly emphasised (we have to face this fact) at the area holding back the phallus. So for a moment, Minton rides triumphant for me from this exhibition. Somehow, that is the case despite the intention of the show. Buy the catalogue too for Minchin’s great essay but skip over the mistake made by the Falmouth Art Gallery director to invite a contribution on the artists from a professional astrologer. It is bizarre (‘the first thing that leaps out’, of their composite astrological chart, ‘is their excessive need for frolics’.[23] Come off it, Reina James.

All the best

Steve

[1] Julian Machin (2021: 7) ‘Freud, Minton, Ryan: unholy trinity’ in Henrietta Boex Freud, Minton, Ryan: Unholy Trinity Falmouth, Falmouth Art Gallery with Victoria Art Gallery, Bath & the Art Fund. Pages 7 – 15.

[2] Ibid: 14

[3] Julian Machin (2009: 48) Adrian Ryan: Rather a Rum Life Bristol, Sansom & Company Ltd.

[4] Mark Brown (2021) ‘Exhibition brings to light young Freud’s love triangle’ in The Guardian 10th July 2021, p. 4.

[5] Machin (2009: 78). Also available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/jul/09/lucian-freuds-gay-relationships-explored-in-new-exhibition

[6] Ibid: 88f.

[7] Ibid: 89

[8] Mark Brown (2021) op. cit.

[9] Cited ibid: 99

[10] Cited Machin (2009: 129)

[11] Ibid: 128

[12] See ibid: 103

[13] Minchin (2021; 11f.)

[14] Ibid: 10

[15] Minchin (2009: 121)

[16] See ibid: 29f.

[17] See ibid: 47

[18] Mark Brown, op. Cit.

[19] Decide for yourself by seeing Machin (2009: 77).

[20] Frances Spalding (2005: 219) John Minton: Dance till the Stars Come Down Aldershot & Burlington, VT, Lund Humphries.

[21] Ibid: 220

[22] Victor I. Stoichita (trans. Alison Anderson) (2005: 4) The Pygmalion Effect: From Ovid to Hitchcock Chicago and London, The University of Chicago Press.

[23] Reina James (2021:5) ‘’unholy trinity: an astrological portrait’ in Henrietta Boex (op.cit.: 3 – 5)

Hi Steve,

Thank you for your interesting piece, hinting at various likely symbolic defences manifesting in the art of these men (I think you meant iconography?). Also, btw, according to Wikipedia, Freud acknowledges 14 children, 12 “by mistresses”.

Best wishes,

mugsey

LikeLike