‘People don’t live like that anymore… and so the literary salon has been snuffed out, and become almost extinct like the maiden aunt and the man of letters’.[1] Should we mourn the Crichel Boys? Reflecting on Simon Fenwick’s (2021) The Crichel Boys: Scenes from England’s last literary salon, London, Constable (Little, Brown Book Group).

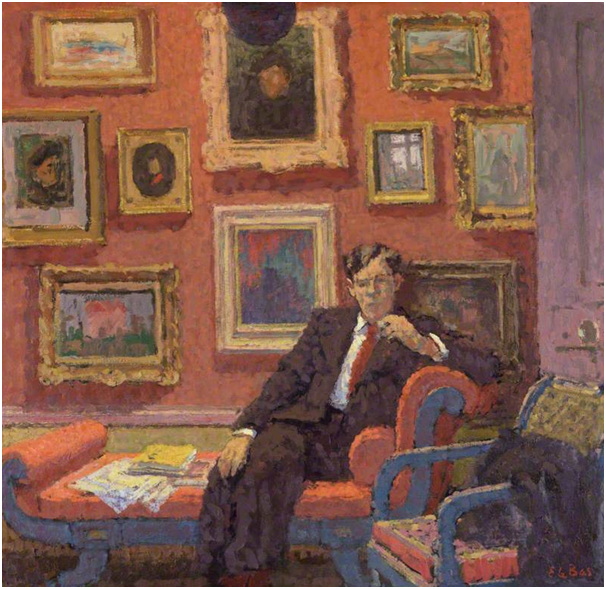

Somehow, in describing this book you have to start with last things: a collection of little lives that are dead not only in the flesh but perhaps in the memory of current readers too. The flesh of many of the Crichel boys was once thought wondrous beautiful by some in and out of the group in which they lived as ‘confirmed bachelors’. Of course, you need to remember the appellation ‘boys’ could once be used of people with a degree of august social presence and of a certain age (well beyond that of a boy child) n the mid twentieth century. The very names of these ‘boys’, once well known in ‘their time’ have now passed beyond us into thinly recollected memories; a degree of oblivion that extends even to their written records. Yet it keeps reminding us – from the dust jacket cover onwards that the men in this book were once both attractive and able to attract public and private attention. But who now remembers Raymond Mortimer, even as a populariser of the Bloomsbury Group? On his death however, his friends were shown two packets of passionate love letters to Raymond from the slightly better known Harold Nicholson, which far surpassed any expression of bodily desire received by Nicholson’s wife.

On the cover of this book, this attractive young man (not conventionally attractive according to Fenwick), who is Raymond Mortimer, turns from the comfort of his armchair to share not only his good looks but an urgent thought or two. That he shared these things with Duncan Grant and Edwin Morgan Forster (very much better known names) too is not now visible to us. The last chapters of the book records the deaths of these men one after one.

The elegiac tone you find in these pages applies though to what these lives mean, or once meant, and I might have preferred that Fenwick was clearer about why they earn our interest as readers. The idea of the ‘literary salon’ as a focus of our interest is only vaguely defined in this book despite its appearance in the quotation in my title and subtitle of the book itself. All we know is that literary figures of the time felt able to descend on this house and to talk about the issues that animated their art – such as conversion to Catholicism in the case of Graham Greene and Evelyn Waugh.

Yet even the chapter headings show that characterising the group of four men who lived together at Crichel House during the longish historical period covered by the book were often characterised in very different ways. To Eddy Sackville-West and Desmond Shawe-Taylor their ‘longing for close companionship’ was translated into the terms of the semi-religious communities known as Bruderhofs on 1920s and 1930s Germany (until suppressed by Hitler), wherein men could ‘follow the teachings of the Sermon on the Mount’.[2]

Another strand of this book concerns the way in which Crichel House became the focus of a new conceptualisation of English history, especially the history of exclusive and very large homes for the very few, that remains instituted in the National Trust, and which to some defenders of the landed gentry seemed the most appropriate defence against a possibly hostile new Labour government, which could be, as was, persuaded to share the view the ‘Country House Problem’ as a national and urgent one. In 1947 Harold Nicholson used Crichel House as a base to explore those country houses as examples of the ‘lovelier vestiges’ of an unfair and unequal past.[3]

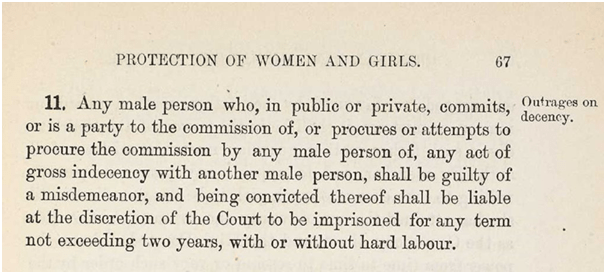

However, in the light of the severe marginalisation and ‘othering’ of gay men that began to show itself in Britain after the Second World War, it seemed to many others, including literary giants, that this was a community offering relative safety to men who lived with varying degrees of openness as queer men. Even heterosexual men could find solace in company that was dominantly male and Cyril Connolly told his female partner, Lys Lubbock, in 1952 that he felt he could ‘stay there forever and become a King of the Queers’. Evelyn Waugh could describe, without any attempt to be offensive since even Lytton Strachey preferred the term ‘bugger’ to describe his sexuality, Crichel as the ‘the buggery house’ to Nancy Mitford.[4] Seeing the house then as a literary salon doesn’t quite comprehend the meanings Crichel House acquired, lost and transformed during its heyday. It was remote and safe, when queer men (even very socially privileged ones like Lord Montagu of Beaulieu, whose story is again summarised near the end of the book) were not as a rule.[5] This, for me as a reader is the most compelling reason for honouring its memory. Read in this way, this book is a great contribution to LGBTQ+ history and I would have preferred the author to present it as such.

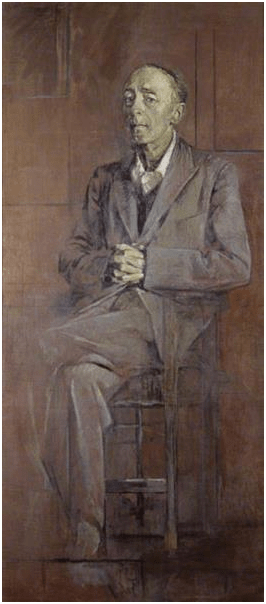

For instance, though it is Raymond Mortimer’s story that focused my interest most, the life of Edward Sackville West matters to our history – not least because his tortured Catholicism and depressive demeanour. That demeanour is well characterised by Graham Sutherland, whose recording of the bodies of queer men, and alliance with giants we are forgetting like David Gascoyne, is being forgotten together with the once monumental importance he had as an English artist. His sister’s, Vita, sad but humorous summary of the picture as ‘Eddy to the death’ is apt but Ben Nicolson is more so in saying that this painting is a ‘magnificent image of controlled distress’.[6] For, the current belief that gay liberation has been fully achieved is, I think, just plainly wrong and we do an injustice to our history if we forget that we still live with some of its darker inheritance as queer people – especially in the awful divisions that have created the Lesbian and Gay Alliance as a front for intolerance to transsexuals. We owe to yourselves to not forget that Eddy, and many of his contemporaries as sensitive as he, truly represented an effect of an oppression that undermined the deepest level of even privileged men’s characters. Eddy is always usually remembered as a great English eccentric, with appalling taste in interior decor. However he said of this painting in 1955 (writing to Sutherland himself):

I always expected you to find me out & of course you have. The picture is a portrait of a very frightened man – almost a ghost, for nothing is solid except the face and hands. All my life I have been afraid of things – other people, loud noises, what may be going to happen next – of life in fact.[7]

‘Controlled distress’ is a means of coping with a loss of safety so profound that it hurts us to even attempt to maintain that control. I sense this even in his fateful attempt to win the love of Elizabeth Bowen, the novelist, and all that would entail whilst she maintained his alcoholism, against Mortimer’s caring refusal of co-dependence.[8] I sense it in the fact that his closest friends spoke of him as a lightweight, or ‘Dilettante’ in Lord David Cecil’s terms, and knew not, if Eardley Knollys’ example is to be cited, how to mourn him.[9]

After having read it, largely for the sake of gleaning a little more insight into the life of Raymond Mortimer, who could say of the painter Ingres that: ‘He is an odd instance of a reactionary genius’.[10] This is more than just parroting Roger Fry, it is a call to progress and social change, and reminds us that he was one of the few to challenge F.R. Leavis for lacking a sense of the ‘diversity’ required in studying literature.[11] But I still love him because, despite sometimes having curmudgeonly ways, he was the only one of the four ‘boys’ who seems to have stood up for the values of their alternative liberal lifestyle and lived with it as a queer man glad to be that. This arrangement may have been a necessity of an oppressed society that he could not change, or felt he couldn’t but everything in his life showed he made a go at making it work with recourse to reactionary values. Yet why I like him I still can’t say, but then when Harold Nicholson fell in love with him he said of Raymond: ‘what and who are you to have secured so masterful an obsession’. I feel a little like that of him despite the fact the ‘more a Liberal and less a Socialist’, in the view of his editor at the New Statesman.[12]

I have to say that all this amounts to is me stating that I like this book and like the pictures of the dignity some men achieved in an oppressive past for queer men, despite the persistence of the invalidation they faced in social terms. If you enjoy queer histories, you will both enjoy this and become, as I did, a bit impatient for it to focus more consistently on this theme rather than, say, the history of the National Trust. But enjoyed it all, I did, I have to say.

All the best as ever,

Steve

[1] Fenwick (2021: 322)

[2] Ibid: 49

[3] Ibid: 57

[4] Ibid: 185

[5] Ibid: 319

[6] Ibid: 322

[7] Ibid: 322

[8] Ibid: 140

[9] Ibid: 229f.

[10] Raymond Mortimer (1932 18) A Letter on the French Pictures: The Hogarth letters No. 4 London, The Hogarth Press.

[11] Michael Yoss (1998: 10) Raymond Mortimer: A Bloomsbury Voice London, Cecil Woolf Publishers

[12] Ibid: 51

4 thoughts on “‘People don’t live like that anymore… and so the literary salon has been snuffed out, and become almost extinct like the maiden aunt and the man of letters’. Should we mourn the Crichel Boys? Reflecting on Simon Fenwick’s (2021) ‘The Crichel Boys: Scenes from England’s last literary salon’.”