‘Your hearts were joined, beating in unison, but then they fractured, blood pooling and spilling in the darkness, and then they broke and that was that really’. [1] From cliché to experience at times ‘when language fails us’ in Caleb Azumah Nelson’s Open Water, London, Viking (Penguin Books).

How transferable is the experience of oppression between the issues contingent upon our intersected social identities? Can I as a white queer male really understand the experience of a black heterosexual young man or do I rely on assumptions or clichés from sources that are ubiquitous in culture and coloured by the hegemonic values that privilege me over him in some ways but not in some others? Of course in all this, we need perhaps to remember the immense weight and power of post-colonial racism given the weighty sludge dumped on non-white cultures by it. However, are there reference points in comparing experiences of oppression across identities that sometimes intersect? It matters when we talk, for instance, about the discourses of embodied love. In that latter case, we might start with the quotation inevitably about the love of a heterosexual ‘couple’ that I cite in my title: ‘Your hearts were joined, beating in unison, but then they fractured, blood pooling and spilling in the darkness, and then they broke and that was that really’. [2]

Yet this quotation concerns me as an exemplar of written language in a novel. The first two phrases seem tame and perhaps best understood as clichés in the expression of love: ‘hearts that beat in unison’, for instance is almost a bathetic phrase. Yet when I read on, something renders that opening cliché alive again. I suspect it is the visceral extension of the tired image of the ‘heart’ so that it is an organ that not only ‘breaks’ (in the clichéd form in the language of romantic love of a response to loss) but also fractures at its joining points and bleeds, more precisely spills blood. And we are reminded that knife crime and racist discourses about knife crime, and their link to the cultural validation of white fears of black men, also play a part in this novel.

We are unused to this turn of the cliché to matters of actual anatomical detail. And the narrative can even admit that the revival of cliché is perhaps an illustration of the fact that there is ‘a reason clichés exist’.[3] This book mourns not only the losses involved in the content of the experience of young black people but of the very means by which we might express and thus, perhaps, relieve that loss; ‘Language fails us, and sometimes parents do too’. The problems in this novel is that identities don’t have discrete boundaries – they spill over into each other and that metaphor of spillage emerges from some deep wound in the novel’s psyche and the musical rhythms of its poetic prose frequently. See, for instance here where the phenomena of birth and primal vulnerability, the sense given by the way that art, and music especially, only has continuities by building in breaks and discontinuities into its form and where the deepest confession (of your loss of God and meaning for instance,you might make of that inner vulnerability when someone, by your beloved grandmother, dies feels like that which spills out of a broken container or a tear in a beloved fabric of your skin or clothing instituted at your bloody birth:

This pain isn’t new but it is unfamiliar, like finding a tear in a piece of fabric. You cry so hard you feel loose and limber and soft as a newborn. … You’re wailing like a newborn. You’re alone. You don’t feel in rhythm. There’s nothing playing. The music has stopped. A break: also known as a percussion break. A slight pause where the music falls loose from its tightly wound rhythm. You have been going and going and going and now you have decided to slow down, to halt, and confess. You are scared. You have been fearful of this spillage. You have been worried of being torn. …[4] (my italics)

It is worth pursuing other examples of this rhythmic recurrence of the expression of this phenomena of the fear of the broken surface or shattered container, wherein the link to mental anguish lies in the exploration of Black identity in the book. It is link to psychological suppression in that wonderful and shattering chapter (Chapter 12) in which the writer, talking of self as usual in the third person, says: ‘You would like to talk about the suppressions’. Suppression is a kind of conscious or unconscious act of exclusion of something as well as having meaning in biology and politics.[5] But it’s opposite is a kind of confession like disclosure or ‘spillage’: ‘To be you is is to apologize and often that apology comes in the form of suppression. … That suppression knows not when it will spill’.[6]

And that original spillage of blood at parturition joins other such spillages in the novel, either accidental or collateral to the damage experienced from institutionalised and other racism: ‘Your hand is bleeding and you’re sucking the spillage from your thumb: …’.[7] And though it doesn’t use the word ‘spill’ overtly,’ (t)here’s a lot of blood’ when Daniel is killed in an incident with a car that is not an accident.[8] It is this bloody spillage that speaks out of the fracture in the love relationship in this novel and in the fracture of a black mind. Listen to it again in this context: ‘but then they fractured, blood pooling and spilling in the darkness, and then they broke and that was that really’. [9] Now the links in the novels themes are addressed succinctly in James Donker’s review of the novel in The Guardian:

In its interweaving of the romantic arc with meditations on blackness and black masculinity, this affecting novel makes us again consider the personal through a political lens; systematic racism necessarily politicises the everyday experiences of black people. The police profiling that the photographer endures as a young black man moving through the city is recounted with painful emphasis on the effects of feeling constantly observed. Azumah Nelson emotively demonstrates how these pressures influence black men’s psychic lives and their forging of connections with others.[10]

My only reservation about this, because I admire clarity that I never myself fully achieve, is that ‘emotively demonstrates’, wherein emotion is seen as a stylistic addition to something that could perhaps be said without such spillage into the novel’s language. I am currently studying an OpenLearn course on Phenomenology and I expressed therein, in answer to one oof the courses questions requiring learner participation that I had been attracted to the phrase in a proffered interview about phenomenology that it helped us: ‘to understand more nuanced and detailed aspects of their experiences.’ I added:

This is my main take-away since it starts with the fact that people think falsely that they already have the tools to enter into other lives without either experiencing them or listening to people who have expressing that experience in various ways. A good example is Caleb Azumah Nelson’s’s new novel Open Water published by Viking (2021) about articulating the experience of the black male body in an oppressive society like Britain. You have to listen carefully to see patterns of reference – for instance between ideas of feeling contained and ideas of ‘spillage’. Only if you allow the comprehensive range of metaphors around these sensations / emotions do you understand in a fully nuanced way. Yet whether i understand from within a white male body, privileged by that circumstance I will never know but by testing those understandings in practice and not as ideas but experiential contact – maybe even only in ‘art’, as the book itself suggests.

My reservation is then is that Nelson’s written art is not about ‘emotive demonstration’ of a fact of life but the direct articulation of that fact of life as a confession of vulnerability in the only possible way, through the patterned signs that evoke emotional response in art. This is why, I would say the book is about the arts practiced by its lovers – a photographer and a dancer and constantly cites the practice of writers who produce art of the highest order from Black experience: Zadie Smith and Kei Miller, for instance.[11] Donker refers to this tendency in the novel by saying that: ‘Azumah Nelson namechecks black artistry of all kinds, often drawing attention to its immersive power and transcendental effect’.[12]

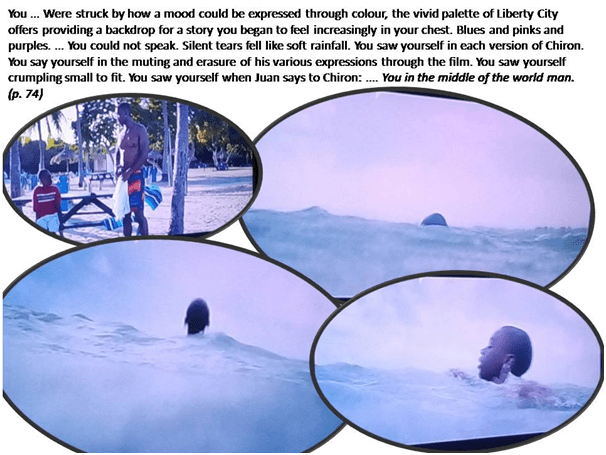

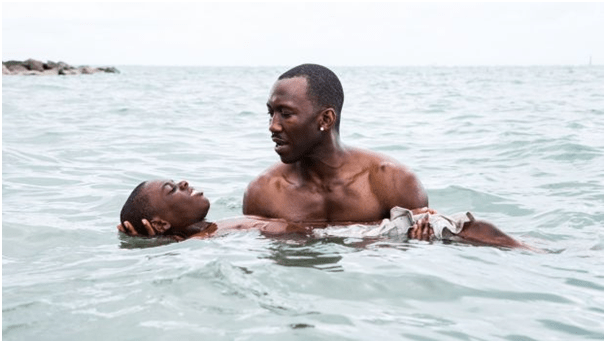

But for the purposes of my own argument I want to take another articulation in art of the experience of Black bodies from the novel, precisely because it is the one that gives the novel its title and the existential crises that are patterned around that title: open water. This art work is Barry Jenkins’ stunning film of 2017 Moonlight. I use this too because it too references the way intersectionality works in this novel because this film is not only about the fragmentation and suppressions from which Black experience is moulded in an unequal and racist society but also about the experience of black queer men. Yet it becomes the motif for the narrator of Open Water, which is set at the time the film was produced according to Donker’s already cited review. Because the experience of being alone in open water and finding a means of embracing one’s own independence in that medium is a linking experience of both artworks, as the collage below tries to illustrate:

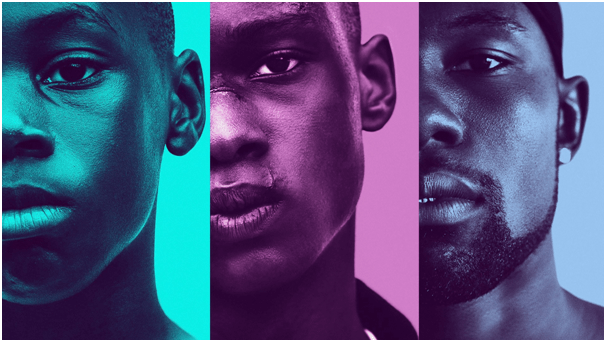

If the motif of a child left suddenly able to feel they are alone in an alien medium in which they felt feel able to negotiate independently is a fairly existential theme, which I think it is, and unrelated to specific oppressions another aspect of Moonlight picked out in the novel is not and emphasises how commonalities in intersecting oppressions can mould joine-up, but nevertheless fractured identities ready to break from the internal force of experienced suppression. This is the moment in the quotation cited in my collage (for which I need another illustration from the film) that the narrator feels he ‘saw himself in each version of Chiron’. This references Jenkins decision in this film to cast three actors for the three distinct versions – fractured by a silent blackout and then, after a prologue titled by a new name for the current dominant identity in the biographical development of the character: (i) Little, (ii)’Chiron’ and (iii) Black. In the publicity material these three versions are also associated with the three colour sets the narrator of Open Water uses to typify the materials of the film: ‘Blues and pinks and purples’.[13]

Barry Jenkins, the film’s director who claims some elements from his own life appear in this film, deliberately never allowed the three actors who played these roles to meet each other yet marvels at how we experience commonality as well difference between the performances. Yet the need for difference lies in the fact that we need to understand suppressions in the process of identity development under social oppression. After all, that which is ‘joined’ must also be that which fractures. And that is the commonality between film and novel: ‘your hearts were joined, beating in unison, but then they fractured …’. suddenly what I presented as a possible cliché is not that but a fact of lived experience, that contains the seeds of both community and division of feeling.

She’s trying to understand what passed between you that night, and simultaneously understanding that she cannot comprehend. … More immediately, the five-day stretch in which you barely left each other, in which nothing really happened but two friends sharing a bed and knowing an intimacy some never will. That is to ask, what is a joint? What is a fracture? What is a break?[14]

Because the novel contemplates the possibility here that there can be nothing communal in the face of continuing and continuous oppression: no joining together that is not ripe for breaking up. At one point the novel reaches out to a theory of development in the longue durée of black history from Saidiya Hartman.

Saidiya Hartman describes the journey of Black people from chattel to men and women, and how this status was a type of freedom if only by name: that the re-subordination of those emancipated was only natural considering the power structures in which this freedom was and continues to operate within. Rendering the Black body as a species body, encouraging a Blackness which is defined as abject, threatening, servile, dangerous, dependent, irrational and infectious, finding yourself being constrained in a way you did not ask for, in a way that could not possibly contain all you are, all that you could be, could want to be. That is what you are being framed as, a container, a vessel, a body, you have been made a body, all those years ago, before your lifetime, before anyone else who is currently in your lifetime, and now you are here, a body, you have been made a body, and sometimes this is hard, because you know you are so much more.[15]

This breathless passage is more than a description of theory. Its form dramatises how sentences too are containers from which an excess of emotion and emotion spills, such that they generate impossibly lengthy and irrational structures like the final sentence I quote above. Being contained in a body is the source of that fear of spillage from that container that has already been rehearsed in an attempt to ‘structure a narrative around the conflict bubbling inside you’, and read to his lover. It is one of those moments when he realises yet again that though he now expresses himself in writing rather than photos (which ‘have their own language’) that in writing too ‘even this language fails’.[16] This struggle with artistic expression is part of the dilemma of the novel but also a vindication of art. And the content of this language is an attempt to understand why a Black boy with a knife might ‘outlet his anger on another’ and moreover ‘in another who looked just like him’ and spill his blood.[17] And at the heart of this dilemma is the Black body as continually reinvented by white privilege as a Body to be feared, and symbolised in ‘sus laws’, which play such a large part in this novel, as they do in fact in the lives of young Black men.

That anger which is the result of things unspoken from now and then, of unresolved grief, large and small, of others assuming that he, beautiful Black person in gorgeous Black body, was born violent and dangerous; this assumption, impossible to hide, manifesting in every word and glance and action, and every word and glance and action ingested and internalized …[18]

Now this passage follows immediately after the passage about the film Moonlight and I do not think it is stretching the associative manner in which this novel works that that the ‘beautiful Black person in gorgeous Black body’ is also a reference to the character’ Black’ whom Chiron becomes. For Black is a showy gangster like Juan. Juan was the drug-dealing mentor who showed him how to swim in ‘open water’ when Black/Chiron was a child known as ‘Little’. But the nickname ‘Black’ was given to Chiron first by the man who, as a boy, first loved him when both were teenage boys. Yet it is this eventual lover (the film ends with them in each other’s arms) who also wants to expose to Black that it was not necessary for him to become the hard and violent man he is and that is not what he is.

These correspondences gets very near to analysing not only black experience but the experience of all men trained to find expression only in mutual violence rather than love and male to male connection, regardless of sexuality. Yet it would be a mistake to divorce the theme of the artistic exploration of identity from a deep concern that primarily focuses on black experience. We already know that the narrator turned to photography as an art in order ‘to document people, Black people’.[19] But he learns that this is to study an essential alienation from one’s own body because that body is stolen by the gaze of white power upon it: ‘…, you pass a police van. They aren’t questioning you or her but glance in your direction. With this act, they confirm what you already know: that your bodies are not your own’.[20] If your body is not your own then that body is, as he understands Zadie Smith to be saying in all she writes that ‘happy endings’ are nearly always things to which ‘a young Black man’ cannot attain, ‘more often than not’.[21]

And there is nothing like a happy ending. We return to the ‘open water’ in which Chiron in Moonlight learned to swim but it is a return that, far from being a world in which to swim, as it s for Chiron, but one in which one might deliberately drown. And, in the end, Black experience, including mental ill health and thoughts of suicide consequent feeling one is trapped without real choices of action, can only be expressed ‘when you chose to write this’ (this book of Open Water).[22] Despite the fact that ‘(l)anguage fails us, always’, it may be the only way of knowing ‘what freedom looks like’.[23]

So, let’s end by asserting that though oppression is specific to the experience of each oppressed group, there are links that art can discover, since it asserts the fact that we can see each other in our own light as intersecting oppressed groups but that we need to understand one very difficult lesson in this novel: ‘Seeing people is no small task’.[24]

All the best as ever,

Steve

[1] Nelson, C.A. (2021: 144)

[2] Ibid:: 144

[3] Ibid: 48

[4] Ibid: 31f.

[5] Noun: the action of suppressing something such as an activity or publication: “the heavy-handed suppression of political dissent” MEDICINE: stoppage or reduction of a discharge or secretion, BIOLOGY: the absence or non-development of a part or organ that is normally present. Brief version of definition on https://www.google.com/search?q=suppression+meaning&rlz=1C1CHZN_enGB960GB960&oq=suppressions&aqs=chrome.1.69i57j0i10l9.1560j0j15&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

[6] Ibid: 61 my italics

[7] Ibid: 79

[8] Ibid: 120

[9] Ibid:: 144

[10] Michael Donkor ‘Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson review – an exciting, ambitious debut’ in The Guardian (Fri 19 Feb 2021 07.30 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/feb/19/open-water-by-caleb-azumah-nelson-review-an-exciting-ambitious-debut

[11] See for instance reference to Miller ibid: 29 and to a conversation with Zadie Smith, amongst other references, ibid: 39f.

[12] Donker op.cit.

[13] Ibid: 74

[14] Ibid: 56

[15] Ibid: 131. Nelson’s own italics.

[16] Ibid: 75

[17] Ibid: 76

[18] Ibid: 76

[19] Ibid: 12

[20] Ibid: 102

[21] Ibid: 40

[22] Ibid: 145

[23] Ibid: 143

[24] Ibid: 145

4 thoughts on “‘Your hearts were joined, beating in unison, but then they fractured, blood pooling and spilling in the darkness, and then they broke and that was that really’. From cliché to experience at times ‘when language fails us’ in Caleb Azumah Nelson’s ‘Open Water’”