‘ … “I sold myself,” he said in a low voice, looking at the table, “To men….// “That night, he went on, the man who had picked him up forced him to do things he didn’t want to do. The man was English. He drove an expensive car. A Lexus. It was black’. [1] The art of making stories correspond quite queerly in the portmanteau novel: Rupert Thomson’s (2021) Barcelona Dreaming, London, Corsair (Little, Brown Book Group).

For Rupert Thomson’s horror thriller, written as Temple Drake, review see this link. For the wonderful Never Anyone But You review, link on that title.

Some novels, especially those with multiple story-lines make us into detectives as we follow the links made by the novelist. When Dickens wrote Bleak House (between 1852 to 1853) he was wonderfully aware of that; creating one of the most archetypal of literary detectives, Inspector Bucket, to help us in realising the urgency and mysteries involved in the task. But the task is somehow much more pressingly present when the multiple narratives, though inevitably, being in the same temporal and topographical space, as in this novel, they touch on each other, are presented serially, one after another. There is fun to be had therefore in finding references to the appearance, for a time, in the city and for the football team of Barcelona of Ronaldhino, which is of course a verifiable historical fact if the stories about him sometimes, especially in this novel but even those in newspapers, aren’t.[2]

The reviewers from the Guardian group of newspapers can back me up. Nicholas Wroe in The Observer says too of Ronaldhino before showing other ‘intricate layers of connective tissue between stories, characters and locations’ between the narratives in the three serial chapters. (Amy by the way is the name of the narrator of the first chapter):

… Amy’s friend Montse also turns out to be Nacho’s first wife. And Montse and her new husband are close to Jordi, a translator of literary fiction in the final story, “The Carpenter of Montjuïc”, whose entanglement with a shady British businessman unhelpfully impinges on his long, and unrequited, love for a woman he had known since schooldays.[3]

Rob Doyle in the Guardian’s own review interprets these connections as an element of realism in the grasp of an urban community and sticks with characters rather than places and narrative types:

Characters who are central in one story hover on the peripheries of another. Nacho’s ex-wife, Montse, and her professor husband are friends of Amy; Montse re-emerges to work on a translation project with Jordi in the final story – and so on. The effect is one of uncontrived urban community, the bustle and musical chairs of real life.[4]

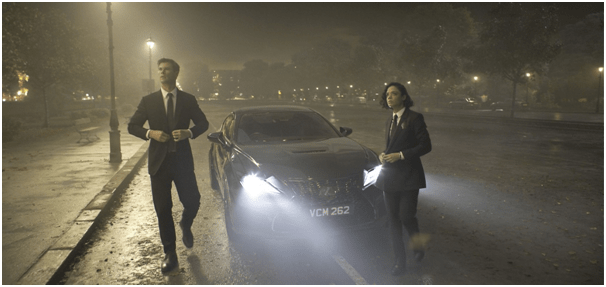

I prefer Wroe’s take to Doyle’s because it hinges on what the former calls the ‘unearthly’ elements in these stories but which I think also preferences the queerly inexplicable events in ‘connective tissues’ that are not easily explained and easily punctured by a sense of meaninglessness. And this is why I chose the citation I do for this novel. It concerns an incident that appears confined to the first story only just as are intriguing characters like Senyor Artes and the giant of the story’s title, Baltasar Gallego Magallón. Both of these characters provide material for understanding the moral panic that stems from immigration from Morocco. Indeed, Amy even researches the issue by consulting Xavi (his one mention in the whole novel), ‘who was a sociology professor at the university’. It is difficult though to know if Artes is indeed a study of Catalan nationalist racism as to Amy he seems when armed with Xavi’s view that Moroccans in Barcelona ‘felt marginalized, and were the object of racism and discrimination’.[5] My title citation is from a belated revelation from a young Moroccan Amy encounters in her garage called Abdel ben Tajah (giving the full form of names is itself a mysterious element of this part of the novel) that a ‘dark stain on the back of his jeans’ (later called, with less morally weighted association, a ‘wet patch’) she sees as he sobs derived from an experience of unwanted and unprotected anal sex received from a client of the prostitution he practices to survive.[6]

This reference to male prostitution as a means of survival for the oppressed just hangs there in the novel like an insight into oppression for which little other context is provided but leaving questions about the nature of the relationships between privileged and marginalised groups that won’t go away. And about the ‘client’ who raped him there appears to be a silence, just as, in the ‘real’ world there actually is about most examples of rape but including male rape of other males. This perpetrator goes unfound in Chapter 1 and this story despite the fact that this ‘crime’ becomes the focus of a story wherein it is the usual recourse to ‘blame the victim’ rather than the perpetrator. Yet Thomson’s novel (or Temple Drake’s) rarely work like that. Let’s take the fact that we know, incidentally from Abdel that he: ‘the man was English. He drove an expensive car. A Lexus. It was black’.[7] It is an insignificant enough detail or at least would be if it did not recur, without linking comment in relation to another character in another story, one not otherwise involved in Chapter 1 and whom we cannot identify just because he owns the same car as the rapist. However, the point hangs in the air and in the second story we find that the narrator and focus of that story, Nacho, the first husband of Amy’s friend, Montse (first met in Chapter 1) and the publisher of the translations of Jordi Ferrer, the narrator and focus of Chapter 3. Nacho tells a story to identify a road he travels, entirely there for no reason but the contingency of the appearance of the same road. He had travelled it with an English man:

Vic, the guy from London. … That day, we must have seen at least half a dozen hookers sitting on white plastic chairs in outsize sunglasses and thigh-length boots. … To my surprise, Vic stopped on a curve and told me he would be five minutes. I had to wait in his fancy black Lexus while he took one of the girls off into the trees. …[8]

A man from London with an expensive black Lexus who uses prostitutes! Is this significant? And if so, are we meant to notice that that the sex/gender of the prostitute is different in this case. I n Chapter 3 Jordi, in whose story Vic (now known as Vic Drago) plays a large part before he loses interest in Jordi. Jordi leaves Barcelona, with help from Montse’s second husband, Jaume, to continue contracting work for publishers in London and, taking a certain route ‘[o]n a whim’ (the sense that the act was contingent on nothing seems important) he will find himself:

… in an industrial estate, exactly the kind of place where I’d imagined Vic’s warehouses would be. I could picture him on those characterless streets, stepping out of his black Lexus, his gold chain bracelet glinting on his wrist. …[9]

By this point we know from the final narrative that Vic Drago is a man involved in all kinds of sexually exploitative ventures, even attempting to involve Jordi’s part-time girlfriend, Mireia, in group sexual adventures and perhaps a role in a pornographic film. Moreover, Vic’s relationship with Jordi appears, though Jordi himself reports him as if naively unaware, with lots of potential for sexual invitation to Jordi himself. Inviting him for drinks with some friends, partly based on a series of serial familiarities based at first that both are in a small lift ‘and once the door was shut I was so close to him that we were almost touching’:

… . “Bring your girlfriend, if you like.”

“How do you know I have a girlfriend?”

“Obvious, isn’t it – nice-looking bloke like you.”

Was it the fifteen-year gap in our ages that allowed him to compliment me without the slightest awkwardness, or was it because we came from different countries, different cultures? I wasn’t sure. Whatever the truth was, he was able to achieve an instant familiarity, and without having done anything to earn it’.[10]

Are we sure by this point that this is the same man who rapes Abdel? I do not know. We could never be certain. We are picking up hints and clues, as if we were indeed a kind of inspector Bucket. Another point intrigues me. Do I notice the innuendo in this because I am and unexpected pattern in this set of circumstances because I am queer myself and socialised into a culture where things are said tacitly or read ‘between the lines’. What I do know is that Thomson uses such circumstances very often to queer any certainties that readers might attempt to bring to novels from either the conventions of other novels or social norms of open communication.

If I had to say, I think these issues of inexplicable coincidence, or narrative potential in excess of anything required in the surface of the stories, is entirely typical of Thomson although used with increasing subtlety and finesse as his skills as a storyteller have developed over many years of people missing just how great a novelist he has always been, just as David Bowie once said. And when you have been so great and so neglected (relatively speaking) a novelist for so long, you might like Thomson wonder if there are moments when people fail to translate the finesse of your prose into the subtlety of the psychology it represents about the uncertainty and multi-valence (far more than ambivalence) hidden in the intention, speech and action of most human utterance. Thus Jordi, a Catalan translator, translating French for an English reading market says of the narrator, Jeanne, of the French short story is translating for Montse with the instruction, “It’s got to be good”:

At first, I admired her bravado – her unconventional approach to what was essentially a conventional predicament – but as the book evolved, her behaviour became disproportionate, and I began to wonder what kind of monster I was listening to? When did being in the right turn into being in the wrong? At what point did the victim become the perpetrator? … And where, in the end, did the reader’s sympathies lie. These were the questions the novella raised. But the title – Giving – which was obvious and flat, offered no easy answers. ….[11]

If you cannot, like Jordi, see that Vic Drago is playing with you and your relative poverty compared to his riches, then it is unlikely you will really ‘get’ what is happening in any other text. And the point lies in the phrase ‘in the end’. Is there any end to such questions that rise with other questions on their tail? Moreover, this might be especially the case when you fail to see that ‘giving’ is only another way of saying ‘offering’ and comes with no guarantee of satisfaction with the content of that given or offered.

And the queering of every base on which we depend can generate some strong and playful moments in novels, especially in NVK, but it can also show that games that people play are sometimes cruel and exploitative, although explained to themselves as something quite other. For, ‘in the end’ Amy exploits the beautiful Abdel just as much as might have Vic Drago, with the relative certainty of financial and housing stability she possesses the gap between her and Abdel is as great as that between Vic and he. Abdel is ‘dressed up’ to impress rich Europeans.[12] And he is, as she suddenly reveals to Montse, very beautiful. But he is also, as she sees rendered by circumstances very vulnerable: ‘’It was like watching a child pretending to be a grown-up, …’.[13] Does she, can she, exploit children – even sexually. The same question applies to Nacho who takes in his the son, Ari, of an earlier relationship of hers of his girlfriend, Cristiani. It is Ari who connects him to the story of Ronaldhino and relates him to the Barça team and is the source then of that imagined relationship of soccer star to an everyday man of Catalonia. Yet why does Ari turn against the affection of Nacho, expressed either to himself or his mother. It is all a matter of how we access the ‘multivalent’ meanings of English prose through effects of tone, nuance and irony. Try reading these reflections From Nacho on Ari’s looks, for instance, over and over:

Where did his looks come from? His father, presumably. Every once in a while I would search his face for an echo of Cristiani, some nuance I missed, and he would catch me at it and ask why I was staring? In time, though, I began to find the fact that they seemed unrelated reassuring. My love for Ari had nothing to do with the love I felt for Cristiani. It happened naturally, of its own accord. It was unforced, honest. Pure.[14]

There is something hidden here in the very over-assertion at the end of ‘purity’ of intention and meaning, some ‘nuance I missed’. This is queer prose indeed portending to both good and evil depending precisely on the ability to face it without a mask of lies and secrecy. Ari’s refusal to believe Nacho’s stories about Ronaldhino means a lot more than it presents on the surface, it is like a refusal of a tissue of grandiose tissues of deceit by which sometimes some men and some women pretend they love, deceit even believed by themselves though they are not its fool. Nacho realises that Ari is in fact just another conquest lost, another Elsa Slump (I love that name).[15]

I had a strange slow feeling, as though my life force was ebbing away, … Was it hypoglaecemia? Or had I eaten something that had disagreed with me? Then I realized what it was. My love for Ari was draining out of me, and I knew it would be hard to replenish or recapture. I felt emptier than I had in years. Worse still, I could hear Elsa singing in my head, her phrasing sluggish, sinister.

This is the comedy prose of a master who knows the funniest comedy is the saddest and cruellest – and a thing wherein evil as well as good can lurk. If this novel doesn’t convert you to Rupert Thomson, it is possibly because you don’t really know how to read at all – a thing more common in the over-educated than is thought.

All the best

Steve

[1] Thompson (2021: 53)

[2] If you’d like to follow an example the following pages from all three internal stories, each in a different chapter, will help: Thomson (2021: 21, 83, 97, 104ff., 110, 113, 134f., 136, 180).

[3] Nicholas Wroe ‘Barcelona Dreaming by Rupert Thomson review – heartbreak and hope in the city’ in The Observer Online (Thu 10 Jun 2021 09.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/jun/10/barcelona-dreaming-by-rupert-thomson-review-heartbreak-and-hope-in-the-city

[4] Rob Doyle ‘Barcelona Dreaming by Rupert Thomson review – a magical homage to Catalonia’ in The Guardian (online) [Mon 21 Jun 2021 09.00 BST] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/jun/21/barcelona-dreaming-by-rupert-thomson-review-a-magical-homage-to-catalonia

[5] Ibid: 10

[6] Ibid: 5, 24 respectively.

[7] ibid: 53)

[8] Ibid: 129

[9] Ibid: 213

[10] Refer to the entire section from ibid: 144 – 146 for this introduction of Jordi to Vic Drago.

[11] Ibid: 161f.

[12] Ibid; 4

[13] Ibid: 6

[14] Ibid: 86

[15] For Elsa Slump’s story see ibid; 93ff.

One thought on “‘ … “I sold myself,” he said in a low voice, looking at the table, “To men….// “That night, he went on, the man who had picked him up forced him to do things he didn’t want to do. The man was English. He drove an expensive car. A Lexus. It was black’. The art of making stories correspond quite queerly in the portmanteau novel: Rupert Thomson’s (2021) ‘Barcelona Dreaming’”