‘Art and the art world have at times been intimidating, elitist, frustrating, overtly academic, impenetrable, frightening even’. : How aim to highlight the ‘flip side’ of art and the art world: ‘joyous, exhilarating, incredibly EXCITING, encouraging, poetic, and the best kind of challenging’. [1] Reflections on Russell Tovey & Robert Diament ( 2021) talk ART, London, Ilex (Octopus Publishing Group).

A counterweight to my review of Mary Ann Caws (use link to read). The whole references my reflections on the nature of art history and commentary as at the present moment.

Front cover

This book is about people regardless of qualification or background making active choices and articulating them as being the very basis of taking ART. In that sense it breaks nearly every rule, spoken and unspoken, in the world of academic study of the arts . I take it that those rules can be stated thus:

The study of art must be:

- Primed by prior learning and proven qualification, whether on the basis of certificated learning from a teacher or mentored experience. You need to look to the ‘entry requirements of universities and colleges to see this, and even when such qualifications are claimed as unnecessary that is because the chosen course will have built into it foundational learning in basic knowledge, skills, and let’s face values. It is the latter that often get unspoken and which operate to exclude some people who may wish to enter into study but are deemed as yet unsuitable or unready.

- Founded on respect for an appropriate cultural attitude in an appropriate language acculturated for the purpose of such commentary. In the past this partly unspoken attitude has been that of persons from narrow groups such as privileged classes, characterised often as white, Eurocentric, male, heteronormative and concerned with embodied ideals and ideals of the body.

- Based on absorption of knowledge from those recognised as already learned in the particular arts – which rarely mean an artist and often meant a person who has undergone long training in the academy. It is that alone which gives a person a right to being seen to produce authoritative statements of fact or evaluation without recourse to the acknowledged authority of others, which must be referenced. As a result a primary sin is the wish in a relatively untrained and naive student to ‘express their own ideas’. They need to earn the right to own ideas.

Now it is precisely these rules Tovey and Diament break. They invite participation from readers in ideas about and skills involving in talking about and owning art for themselves. The phrase ‘we need to express ourselves’ is a challenge to academic elites and the processes of their production. The art that is expected to engage people comes not with a demand that we absorb its contextual value in the whole history of art but from our prior interests and community commitments, including that of seeing oneself reflected in it.

There are innovative genres which elicit such interest precisely because they derive from current open-ended tastes and preferences rather than that of the archive – that are current and immediate. Hence we start with Performance Art and end with Cartoon Art. What sparks our interest may be a desire for change or inclusion – hence the sections on ‘Art and Representation’, ‘Art and Feminism’ and ‘Art and Political Change’. Even when we deal with feminism, it is not in the etiolated form current in academic departments which has little life outside them, but that which touches on the lives of women and girls directly, which means that its stance on pornography is not predetermined in ways that inevitably exclude certain choices about the representation of one’s own body, to whatever gaze is appropriate to your purpose. Indeed one issue is to avoid the very ways any single culture is acculturated to understand the human form (why, for instance, does it always miss out differently enabled bodies or see them as bodies in deficit as ‘disabled’:

“I think there’s a hunger for all the different lives,” muses Katherine Bradford …; “especially for the ones who were left out of the picture.”…. There was an anxiety, as a self-taught artist, to take responsibility for the figure. “I didn’t dare put human beings in my work, because I’d never been to art school; I’d never done life drawing, all those foundation courses.”… “… I think people want to hear some personal stories, other voices, and I think if you put figures in paintings, you’re able to tell these stories, …[2]

For some women this includes the perspective of the ‘nude model’ or the vulnerability of a young girl conscious of being gazed upon rather than delivering such models to an unaccountable male gaze, which pretends it is not there and therefore not responsible for what it sees. At least this is what we hear Lisa Yuskavage talks about, as she sought to ‘weaponise shame’ on behalf of women.[3]

And it is a pure joy, of course, for me, a queer guy, to see both Tovey and Diament writing so beautifully and openly as queer guys and queer friends. Witness Robert in praise of what the discovery of openness in the art of both Frida Kahlo and David Hockney did for him in connecting him to community and a more diverse humanity as they continued:

…, making paintings, drawings, etchings and photographs about their intimate worlds and desires. They taught me that love existed in different forms and that all love, regardless of sexuality or gender, was valid. Art gave me permission.[4]

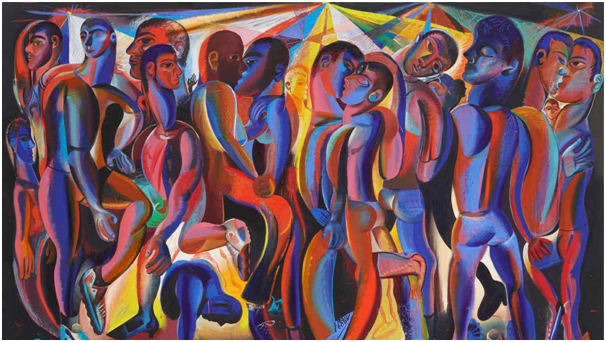

I expect that one could only be distracted from the cringing such words cause in academic common rooms by the self-indulgent laughter at how naive this was from the comfortable lecturers ensconced over a conversation about their tax returns. More so by Tovey’s characterisation as his writing partner as ‘(l)ittle old Robert Diament, with the floppy hair and pop star lifestyle’ because in both quotations we see both sincerity and delight in self-expression and mutual recognition of like souls. At its heart then is, though quite rightly it isn’t segregated to a chapter’ is the concern for truth in the representation of queer diversity, centred (perhaps) on the work of Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings on the Gay Bar Directory.[5] This goes beyond queerness of course to the nuanced way in which black identity and bodies, and glorious multifarious colours are celebrated in clothes and bodies by Amoake Boafa. But of course I loved the introduction to the ‘tender representation of queer love, bonding and intimacy’ in Louis Fratino, also found in this linked interview with the artist by Tovey.

I wondered at myself when I read the comment about the 2020 painting Sleeping on your roof in August, as well of course as other Fratino pieces that ‘they draw you in with their exaggerated hands and feet’ that I was thinking of similarities with Pavel Tchelitchew, more remembered in the USA than here, since that seems like classic art-history influence searching in order to deaden the effect of content, but come to think of it the connection merely supports Fratino’s cited view that for ‘so long I feel like erotic gay imagery gets sequestered into some corner … like “that’s gay art history” [as opposed to just art history]’.[6]

And best of all in terms of international queer art is the introduction to Salman Toor, who contributes one of the best original works of art to this book as the illustrated number page for Chapter 7 with his haunting picture of fragmentation of the queer body Boy Ruins (2020).

The power of this picture lies in part in its sly commentary on the tropes that organise art history – the fascination with the archaic and the reflected and perhaps the fragmentary. There is almost a feel of Chatterton’s suicide in an attic room but there is also a nod to the isolation from the queer community that has historically fragmented queer experience so that its intellectual head is severed, like that of Orpheus, from its neglected and stored to rust body. The phallus neglected behind the mirror seems to me just wonderful. Yet the severed hand still tries to collect together the blood running from that head. It is a beautiful picture I keep returning to.

There is much in this book that in restoring fascination with new and urgent art attempts to link back into the art of the past that has been so severed from life by art history. This Diament talks of being enabled to forget art as it was taught and experienced in schools to refind the ‘actual majesty and profound beauty of the Old Masters’.[7] Thus too we are shown how the photography of Wolfgang Tillmans is ‘breathing new life into the genres of still life and portraiture’ in his amazing grey jeans over stair post (1991) reproduced in the book but available in the Tate collection in the link above. This picture is honestly both fetishist and symbolically erotic with the unseen bed post playing unrealistic phallic symbol behind the open fly of the jeans. Surmounted by a casual top, the stairs themselves betoken a past unrobing and possible event that is physically sexual but also mourns the body lost from the clothes, as if reduced to this moment of solitary and sad grandeur of display. It is remarkable and, of course, it is about ‘still life’ and, of course, about ‘portraiture’. And, of course it highlight the problematic of modernity around notions of stasis and enduring significance, which it must find in fragments of beautiful meaning that is never more than emergent.

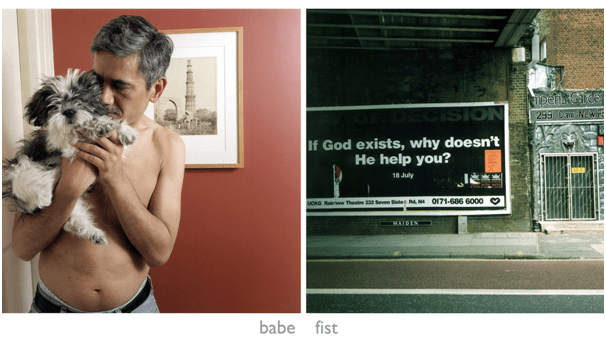

And let’s return for a moment to the invocation of the personal as a welcome intrusion into art history by Mary Ann Caws in my last blog. For Caws the personal is a record of her historic insertion into the world order through family, paid employment and recognized status and all the fine culinary add-ons. For this book it is exemplified in the life and art of Sunil Gupta.

His works weave storytelling narratives, which use the highly personal, his emotional journey after being diagnosed with HIV in the 1990s, and the stories of friends and lovers and the openness he continually finds in the strangers around him.[8]

So read this book about art before any other. It makes things new and it makes learning relevant in ways that will always be the butt of jokes amongst tenured and untenured alike in the academy. Well, we all need our prejudices – best then that they are about institutions that have held monopoly control over our values for far too long. LOL.

All the best

Steve

[1] Tovey & Diament (2021: 11)

[2] Ibid: 97

[3] Ibid: 98

[4] Ibid: 15

[5] Cited and illustrated ibid: 116f.

[6] Fratino cited ibid: 110

[7] Ibid: 15

[8] Ibid: 75