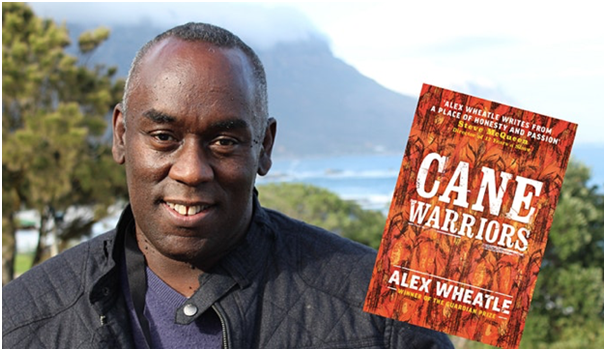

‘We’ll tek our mighty stance again’: Looking at Alex Wheatle (2020) Cane Warriors London, Andersen Press Ltd.

It’s possible that this novel will never be considered for major prizes in literary fiction, like the Booker, since it is written, as Jimi Famurewa says in his interview with the author for The Guardian as ‘a taut, urgent new young adult novel set within the real-life slave uprising …’.[1] That category of ‘young adult fiction’ is designed by publishers for a market of young people from 12 – 18, though even the Wikipedia description of this genre admits that a high proportion of the readers of this genre are adults not describable as in the latter category. Amnesty International endorse the book, in an afterpiece printed within it, moreover, as a means of introducing young people to the necessity of human rights and the anathema of slavery whether from the past or present. Their sponsorship highlights ‘people at risk’ and encourages readers to start a ‘youth group in your school or community’ and references the needs of readers who might be ‘a teacher or librarian’ in a school.

Yet Wheatle knows that targeting his work thus (for ‘children’) contains risks. The risks centre on the supposed need of young adult males for role models. The two central male youths exemplify this since both seek and, in a sense, find such models. The central one is Moa (who at 13 is its narrator) and his older friend by a couple of years. The age difference matters a lot to the unfolding of the plot in this novel and for the idealisation of the older youth by the younger. For this is a novel that confronts retributive and revenge violence head on as a heroic ideal, describing it even more than the violence of the imperial ideas, practices and authoritarian mechanisms of the white colonists and slavers, usually the focus of art that also educates about slavery such as Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave, which has a 15 certificate officially. This novel refers to white imperial injustices in the stories told by the characters and as plot element, as frequently as it is necessary but to represent the factual history but does not show these incidents of brutal white behaviour except as stories recounted. It does show absolute and terrifying violence against slave-owners and in doing so deliberately takes that huge risk of the distaste of a society where it is still considered contentious to insist on the slogan ‘Black Lives Matter’ over the attempt to replace it, usually from positions on the right of politics by the phrase, ‘All Lives Matter’.

Now this is not because violence is unknown to the traditions fostering the young adult fiction genre, especially that aimed at boys. Again Wikipedia’s description of it argues that the genre was based on the historical success, with boys of that age, of novels that represented trade in slaves in ways that semi-promote the view that black people were responsible for their own enslavement. It managed to represent them as a docile ‘race’ under white surveillance, whilst still representing them as at base or unconsciously as a ‘savage’ or innately violent people responding only to rough treatment. I think we need a citation but I apologise for the offensive language, especially Macdonald Fraser’s casual and typical use of the N-word.

”If they’d had a spark of spirit the niggers could have torn them limb from limb, but they just sat, helpless and mumbling. I thought of the Amazons, and wondered what changed people from brave, reckless savages into dumb resigned animals; apparently it’s always the way on the Coast. Sullivan told me he reckoned it was the knowledge that they were going to be slaves, but that being brainless brutes they never thought of doing anything about it.”

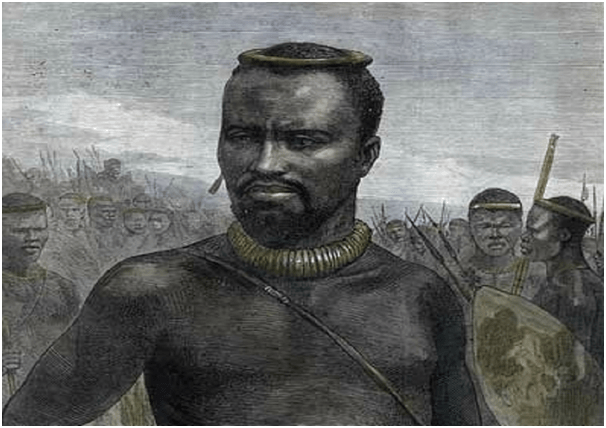

This is from Flash for Freedom first published in 1971 well after the author’s death, which, though it pretends to be antagonistic to slaving and, in this case is about enslaved women, clearly has no thought of representing people of colour fairly. That can be seen even in the books of Thomas Brightwell, who followed on the tradition in the 1980s and thought his representations much fairer (avoiding the N-word for instance) though clearly no-one said anything about fair representation to the book cover illustrator of Flashman and the Zulus, the paperback being published or re-published in 2020, according to Amazon.[2]

Now it may be unnecessary to point to these remnants of the Imperial past of Britain, especially since I think the readers of such fiction are now ‘young adult’ only in their dreams, but Wheatle specifically recalls the effects of an Imperial past in his ‘Afterword’ to his novel, where he says, correctly and without exaggeration in my view:

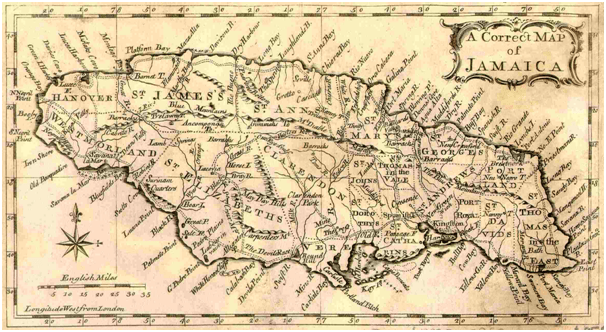

There is no doubt that the British Empire was one of the most brutal and unforgiving in world history. They inflicted their own particular brand of holocaust. Between 1662 and 1807, Britain shipped over 3 million Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to British-owned colonies in the Caribbean. …[3]

Moreover, Wheatle expressed the possibility that he would write on the ‘Tacky’ rebellion in Jamaica in 1760 in an essay published in 2019, and therefore written well before that, as an example of the reasons ‘that Black people carry a sense of injustice in their bloodline’. He even cites, ‘from his Rastafarian brethren’, the phrase that will be repeated many times in Cane Warriors, that ‘the blood remembers’ (Wheatle’s italics).[4] In the novel the phrase is used to describe, at first without the appearance of it being an axiom of an ancient community resistance, the way Moa characterises the callous disregard of black Lives in the slave-owner he, with his friend Keverton, has already killed: ‘Misser Master never offered that courtesy for so many of our passed brothers and sisters. My blood remembered the murder of Pitmon and the death of Miss Pam’ (my italics).[5] Thereafter the phrase takes on the quality of a ritual chant: which energises the rebellion against oppression remembered and a preference in the ‘adult’ slave-rebels for suicide over recapture by the British. For recapture meant subjection to that systematic cruelty which is to be the fate of Tacky himself and his dishonoured body.[6]

There is a reason I refer to that 2019 essay by Wheatle. It makes it clear that its purpose isn’t to explain the origins of retributive feelings in black men (the book is only really about men) but to cite evidence of a continuing irrational fear of black men in white cultures and the consequences of that irrational fear. It’s a theme that is often found in black writers I have read. Witness this short story, Pray by Caleb Azumah Nelson, wherein the narrator’s beautiful and rounded portrayal of his brother, Christopher, is suddenly displaced by what Christopher becomes in ‘police and news reports: ‘they will describe Christopher as though he never had a beginning. That he appeared, whole and Black and mean and threatening’.[7]

Wheatle experienced the fear of white observers he says in his 2019 essay in Brixton in 1978 immediately after leaving the brutal treatment he received in care (this story is told in Steve McQueen’s Small Axe TV play about Wheatle). It amongst other narratives are used as evidenced of the moral panic amongst white communities against black youth where ‘inhabiting a black skin was mistrustful enough for them’.[8] This moral panic, or ‘illogical terror’ as Wheatle names it much more precisely, is associated with the memory, inscribed in the historical and autobiographical evidence he cites, that slave-masters ‘excused their abominable behaviour towards their Black captives by convincing themselves and others that their slaves were animals’.[9] The word “Animals” is precisely the first word we hear Donaldson say on encountering Moa with his treacherous ‘Papa’ and the rebel, Louis.[10]

Moreover Wheatle attributes his experience of own literary neglect to his belief that he ’was seen as a threat, a Black man who made white people feel uncomfortable by my presence and the words I put on the page’, What Wheatle insists he will not do is overcompensate by striving ‘to be perfect, compliant and not seen as a threat or an uncomfortable reminder of a genocidal colonial past’, that generated Sidney Poitiers representation of a ‘good’ black man. He is the black exemplary male, good enough to marry to your white daughter, in the film Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner in 1967 (I remember it well).[11]

I think we need this context to understand the calculated risks Wheatle takes in this novel by emphasising violent retribution against white figureheads. The descriptions foreground characteristics of white skin. Look, for instance, at the focus on that startling ‘red neck’ of the Misser-Master: it’s a phenomenon to which aging white skin is subject in an unforgiving sun. It become the focus of intense retributive hatred: ‘His red neck was ripe for strangling. My fingers wanted to wreak revenge but I gripped the sides of my coarse pants instead’.[12] It is violence that is described with vigour and forensic detail and excludes any editing of the facts and the peculiarities of the emotional response in the moment:

Use both hands, Louis had advised. Dig deep. Twist. Mek sure he don’t breathe another dutty breath.

My aim was true. Just above his left nipple. My blade went in easier than I had imagined it. I turned the blade. He didn’t scream. He just let out this long final breath. It was quite something watching the last moments of a dying man. …[13]

The strategic natures of wars against oppression, and for freedom, are no cleaner than other wars, involving numbers of individual deaths each more difficult to imagine or reflect upon.[14] It involves even the killing of ‘de pickney’, against which the Akan religion, as well as the human feelings, of the rebels itself revolts.[15] But as Tacky is made to say, “every mon here so had plenty reason to out him light”.[16] And, after all though this is a rebellion represented as if fought in the name of the ‘sons of the land of Akan’ (from an African past known to Tacky). But it is prosecuted by some boys, including the teenager Keverton, born in Jamaica of white fathers who had raped their mothers on a systematic basis, and who will, inevitably unless stopped, rape their sisters and female lovers.[17]

Now there is no doubt that the presentation of the Tacky rebellion is idealised and the stuff of boy’s legend, any more than that of any other war in much young male adult fiction. The historical Takyi (sic.) had himself been ‘a wealthy merchant and slave trader himself until he was captured during the Kommender Wars and sold off into slavery’.[18] The short sharp campaign, as it seems in the novel, actually lasted from May to July 1760, with the army gathered by Takyi fighting on well after his death and humiliation after death. The suicide of his followers to forgo return to slavery is also based in history. The historical Takyi is also till thought to be a king of a nation off the Gold Coast in what is modern day Ghana but little is known of his kingdom or of his actual politics, described by Moa in the novel as that of a ‘dreamland’.[19] Moa, looking through the eyes of his love for his friend Keverton, honestly romanticises him and Keverton with him: “… now when me t’ink about it, him walk tall wid ah mighty head ‘pon him shoulder”,. However, when Moa is acting solely as a narrator, well before the last self-citation, he can say: ‘I hadn’t seen Tacky for weeks. He wasn’t that tall, not even that broad, but he trod like a king’.[20] For, as we know from the Jimi Famurewa’s interview already cited, Wheatle himself regrets having enjoyed the Tarzan stories as a youth. For it is in these types of story that young adults form models of achieved masculinity: unfortunately most are those modelled on white privilege and values.

For the boys in the novel what matters is how you stand up to things and this is a theme in much male literature. Even Keverton’s suicide is presented as an act of projective identification with the past of a great and historic Black nation, even if achieved only in a dream of the afterlife: “We’ll tek our mighty stance again’. For me this concern with masculine stance and gesture is central to the novel and will involve necessarily the idealisation of revenge violence in black men, as a counterweight to oppression. Anything less would be to act again like Sidney Poitier’s character in Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner. And this concern with stance is dealt with in the idiom of Jamaican patois: if Tacky ‘trod like a king’ then Moa too ‘trod my good foot’: “Me foot strong, mon …. And me courage fat”.[21] Famurewa picks out of his interview with Wheatle the desire to create, inspired by C.L.R. James’ The Black Jacobins ‘the depictions of nuanced black heroism he was denied as a child’.

Because, up to that point, I’d only seen black people as victims or subservient. To actually read a text where there was an incredible black hero really opened up my eyes to the world. It led me to search for other black heroic texts, because I’d been denied them all those years. So I do feel, with Cane Warriors, that I’ve come full circle.[22]

And violence is part of boy’s fiction – is nascent even in Treasure Island. However, Wheatle’s story is far from as heteronormative as it might appear in the final union of Moa with Hamaya. It’s expressed in Moa’s rather beautiful sentence, “Could me really look after her”.[23] I think the story convinces us that Hamaya can look after herself and that the enslaved women of this story sometimes have a more realistic perception of how one works with racist oppression than males: his mother warns Moa, for instance, not ‘worry your pretty liccle head about dreamland’.[24] The centre of this novel is the boyish bromance of Moa and Keverton, as one of the very source of male fantasy. Had Keverton not promised Tacky to take part in the suicide pact, Moa would have taken him to live in a hut in the hills, away from oppression but not necessarily with sword in hand. The boys may dream of a large house and ‘t’ree’ wives and ‘plenty pickney’ but their pledge is to each other:

Keverton wiped his forehead. “Me want you to know,” he said. “Me glad me wid you.”

“Me well happy me wid you too,” I replied, ….[25]

Meanwhile there is Jamaica, a land in which freedom can be imagined on the other side of the mountain. Tacky actually offers Moa the chance to continue living with his parents. Keverton teases Moa with a heterosexual wish fulfilment, accomplished with a ‘girl with one foot’, because she, “At least cyan’t run away from you!”… .[26] But Moa knows that though he will think of ‘the pretty girl with one foot’ as of his family and that, though part of him ‘wanted to return to them’, it could not happen ‘without Keverton’: ‘We cut de cane together, live together, quarrel together and fight together. Me cyan’t leave him now’. This renewal of a pledge between the boys seems to me not merely fortuitous, especially since Tacky represents Moa soon after this point as a boy who can ‘tek up your good foot and run away’ (which seems to equate his role to that act of desertion a girl with two feet might do) Moa says quickly afterwards; “Me never will run away”. Only the suicide of Keverton stops that ‘never’ coming into being.

In my book, this is an intriguing story that does not flinch from being for black young adults all the contradictory things that sum up earlier young adult fiction which has, unlike this, excluded or ‘othered’ black people. Do read it – whether you are a ‘young adult’ or not.

Yours ever

Steve

[1]Jimi Famurewa (2020) ‘Alex Wheatle: “I have nightmarish moments where my past comes back and hits me”. The prize-winning author’s life is now an episode of Steve McQueen’s hit series Small Axe. He talks about working on the project and his latest novel, based on a Jamaican slave uprising’ in The Guardian(Sat 5 Dec 2020 11.00 GMT). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/dec/05/alex-wheatle-i-have-nightmarish-moments-where-my-past-comes-back-and-hits-me

[2] Amazon Page selling Flashman and the Zulus citing publisher’s description. Available at: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Flashman-Zulus-Robert-Brightwell/dp/1839454512/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=

[3] Wheatle (2020: 183)

[4]Wheatle (2019: 57) ‘Fear of a Black Man’ in Derek Owusu (ed.) Safe: On Black British Men Reclaiming Space London, Trapeze (Orion Publishing Group) , 51 – 60.See my blog on this book using this link.

[5]Wheatle (2020: 59)

[6] Ibid: 128, 138f., 148

[7] Caleb Azuma Nelson (2021: 160) ‘Pray’ in Nelson, C.A. Open Water (2021 in the Exclusive signed Waterstones edition only) London, Viking, Penguin Books.150 – 163.

[8] Wheatle (2019 op.cit.: 52)

[9] Ibid: 56

[10] Wheatle (2021: 39)

[11] Wheatle (2019: 57)

[12] Ibid: 11

[13] Ibid: 53

[14] Ibid: 69

[15] Ibid: 60

[16] Ibid: 64

[17] Ibid: 123. The rape of Hamaya is forecast (ibid: 16 & 176) and motivates the story as an alternative of Moa’s loyalty to Keverton, of which more later – above.

[18] Elizabeth Ofosuah Johnson (2018) ‘The story of Takyi, the Ghanaian king who led a slave rebellion in Jamaica in 1760’ in face2face.africa (online) [September 29, 2018 at 09:00 am] Available at: https://face2faceafrica.com/article/the-story-of-takyi-the-ghanaian-king-who-led-a-slave-rebellion-in-jamaica-in-1760

[19] Ibid: 7

[20] Ibid (respectively in order citation occurs in the sentence):123 & 57.

[21] Ibid: 78

[22] Cited Famurewa, op.cit.

[23] Ibid: 177

[24] Ibid: 33

[25] Citations from ibid: 126 and 124 respectively in order of appearance in the sentence.

[26] Ibid: 126

One thought on “‘We’ll tek our mighty stance again’: Looking at Alex Wheatle (2020) Cane Warriors London, Andersen Press Ltd.”