Subject to another revision perhaps

‘exteroceptive consciousness is predictive work in progress, the aim of which is to establish ever deeper (more certain, less conscious) predictions as to how needs may be resolved’.[1] Reflecting on Mark Solms (2021) The Hidden Spring: A Journey to the Source of Consciousness London, Profile Books Ltd. & a FutureLearn course by Mark Solms and The University of Cape Town What Is A Mind? Just completed (25/06/21).

I finished this magnificent course yesterday and steeled myself to finish Solm’s magisterial book so that I could rite my reflections and move on. I never quite will move on because this is a course and a book which merit ongoing reflection and a lot of reflexivity about your own responses. Yes. I loved the course and felt that it offered continual challenges as it brought together diverse fields, starting with philosophical questions such as: ‘What is a Mind?’, to which it answers with providing four ‘denying properties’, which are then explored week by week. All of these properties are necessary but no one is sufficient, on its own (without that is the other three), in the language of philosophy. These are:

- Subjectivity. But argues Solms subjective and objective are just aspects of being characteristic of all things (even a carpet) so they are clearly not enough though necessary.

- Reflexivity. It feels like something to have a mind. Since this excludes the carpet well and good and places feeling at the centre of the issue. It is, in short, the ‘hard question’ of consciousness dealt either in greater detail in philosophical, neuropsychological and neuro psychoanalytic terms in Solms book, wherein he takes on philosophers like David Chalmers with, as Oliver Burkeman in a review in The Guardian argues with his ‘most arresting claim’ that ‘the answer is to be found not in brain functions such as visual perception or hearing, the usual focus of inquiries into consciousness, but in feelings’.[2]

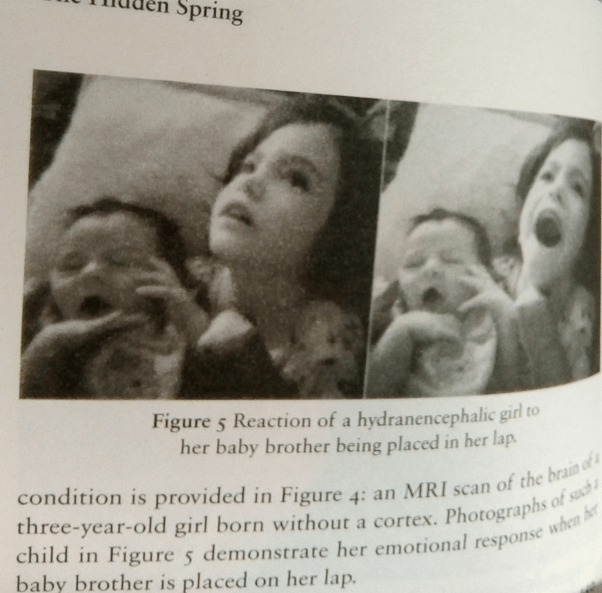

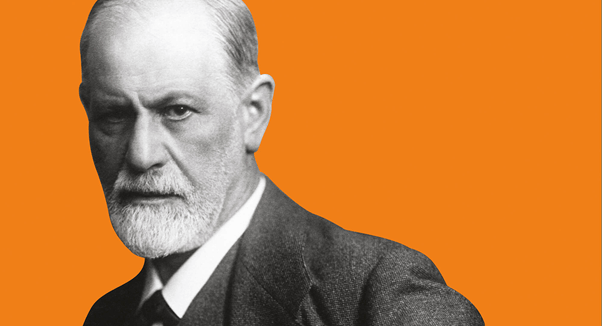

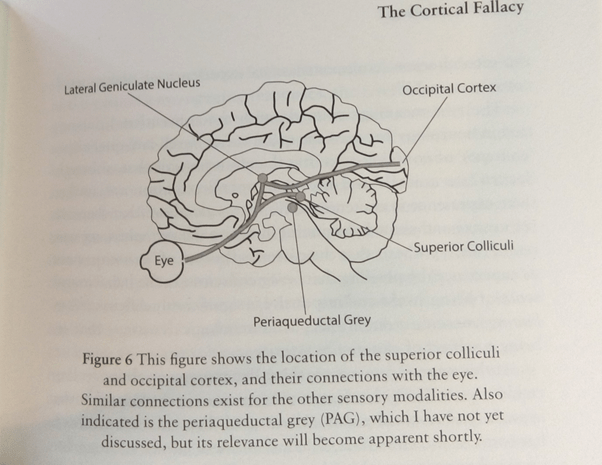

- Intentionality. Minds have an ‘intention towards something, they aim toward an object. They are not therefore self-sufficient. This is needed because it is a function of minds to have unconscious ‘awareness’ (that old paradox) volitions as well as conscious ones. It is here where Freud becomes essential to the historic foundations of Solms theories and is indeed a crucial element, though Freud is corrected y Solms by locating the consciousness (and therefore all ego functions) entirely in the control of the cortex. That position is brilliantly undermined, not least by case studies of hydraencephalic children, who are born with spinal fluid in the place meant for the cortex to develop.

- Agency / Free Will. The person is, or at least feels to be, in control.

The book is more focused on the issue of consciousness than all of the questions raised here but it adds material, especially more detailed case studies that also helped me engage with the course. I have mentioned hydranencephaly but one of the most stunning case studies is one illustrative of a phenomenon that is not confined solely to the clinical realm: confabulation, much more common than people think (see my blog of a task from this course using this link).

But I was pleased that Burkeman in his review admitted to feeling blocked by some of the density of the argument in this book. For instance in elevating ‘emotions’ as the true ‘hidden spring’ of consciousness and locating its neuropsychological source in the mid brainstem rather than the cortex, Burkeman says:

This he attempts in the book’s densest chapters, an uphill climb from the free energy principle in neuroscience, via advanced information theory, to the role of the cortex in the generation of memory, featuring many phrases such as “we can now formalise a self-evidencing system’s dynamics in relation to precision optimisation”. To the best of my understanding, the gist is that feelings are a uniquely effective and efficient way for humans to monitor their countless changing biological needs, in extremely unpredictable environments, to set priorities for action and make the best choices so as to remain within various bounds – of hunger, cold and heat, physical danger, social isolation, etc – outside of which we can’t survive for long. Doing all that without feelings, and doing it as rapidly as survival requires, would take so many computational resources that it would lead to a “combinatorial explosion”, demanding levels of energy a human could never muster.[3]

I think the gist he finds here is sufficient for my own current understanding but stops short of explaining how, in an extra twist of this dense argument, Solms is arguing that the role of feelings will eventually inevitably be able to be modelled on a computer: ‘ an artificially conscious self-evidencing system can be engineered. Consciousness can be produced’.[4] I wish I had known this when I read Ishiguro’s latest novel on artificial intelligence/emotion programming of AFs – Artificial Friends (see this link for my blog – not revised in the light of Solms new book). More importantly, this is a bone of contention between Solms and Antonio Damasio: it is where he ‘parted company with me. … He couldn’t understand why I was trying to reduce consciousness to what he called “algorithms”’.[5]

This density in part comes from Solms knowledge of specific disciplines needed for the understanding of his argument – Between us Burkeman and I have named a few such as philosophy, neuropsychology, digital information processing, psychoanalysis (and neuropsychoanalysis birthed by Solms and others) but we need physics too and I think the need to read this book again (perhaps in parts) shouldn’t make me worried about my lack of general understanding yet.

I knew Solm’s earlier work a little before I did this course because of his return not only to Freud but for the fact Solms trained in psychoanalysis when it was not only unfashionable but a career killer in academic (and to some extent therapeutic) psychology. With Antonio Damasio and others has won the day – no-one know who has any knowledge of the brain will again be able to simply dismiss Freud without reading more than an inadequate summary of his great writing. And Solms shows that Freud, whatever his failings on the location of consciousness in brain pathways and locations,[6] wrote extremely carefully and brilliantly on the key concepts Solms still uses, such as the definition of a ‘drive’. Freud calls it, in Instincts and Their Vicissitudes in 1935:

The psychical representative of the stimuli originating from within the organism and reaching the mind, as a measure of the demand made upon the mind for work, in consequence of its connection with the body’ (my italics).[7]

This placing of the drive as related to the ‘demand for work’ is what enables it to conceived by Solms as part of a homeostatic system for regulating the well-being of the organism in novel circumstances. For such a capacity for regulation in this only guarantee of adaptability to new circumstances that prompt evolution. But it also explains terms in Freud such as the ‘dream work’ or the layers of revision that occur in parapraxes (slips of the tongue). Feelings are ‘hedonically valanced’.[8] They measures states of feeling good or bad based on the success of stored resources for making predictions about what will happen as a result of any action based upon our instincts and enable regulation to change the action, next time at least in the case of adaptive learning, and our stored expectations of a changing world. This is what I gain from this remarkable passage and that which I cite in my title which introduces how the regulation of expectations in a world of uncertainty necessitates a mind that measures its confidence in its own survival:

Everything we do in the realm of uncertainty is guided by these fluctuating confidence levels. We think we know what will happen if we act in a certain way, but do we really? … In the exteroceptive sphere, things are good when they turn out as expected, and badly when uncertainty prevails. Accordingly things feel good or bad: …[9]

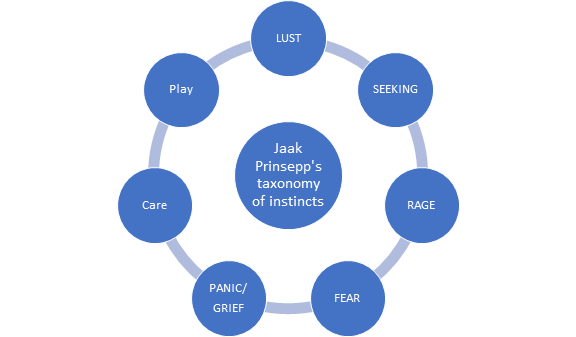

Why is the relocation of consciousness’s physical as a point communicating with cortex and the subcortical structures important then? Because however we categorise the instincts (or drives) and Solms uses Jaak Pranksepp’s taxonomy, shown below in a chart. For this chart I claim no meaning, it is just a way of showing the seven components of that taxonomy.

But something has to make motivated choices between the instincts competition for expression in the real world of uncertainties and their associated behaviours must be based on on some measures of criteria. The measuring tools we now know to be feelings related to predictions the physical something that makes it – the PAG (see note 5).

All the best

Steve

[1] Solms (2021:304.) Page references are to the UK edition.

[2] Oliver Burkeman (2021)‘The Hidden Spring by Mark Solms’ in The Guardian (Fri 5 Feb 2021 07.30 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/feb/05/the-hidden-spring-by-mark-solms-review-the-riddle-of-consciousness-solved

[3] Ibid – my italics

[4] Solms (2021: 305). Solms’ italics.

[5] Ibid: 153f.

[6] In particular the role of the Periaqueductal Grey and its function in modulating the likelihood of neurotransmission (PAG) ibid: 54 for first mention.

[7] Cited ibid: 35.

[8] Ibid: 96

[9] Ibid: 145

Impressive review, which I confess I mostly scanned rather than read, but it sounds like a book I’d like to read. This is my first visit to your blog. I find blogging a lonely and frequently unrewarding pastime because I almost never get a comment; on the other hand, reading the blogs of others seems generally a complete waste of time, so when I find something worthwhile, like this, I usually add a comment. Keep up the good work; with posts like this, you should prosper as a blogger.

Alan

LikeLike

Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person