Graphic Reflections on Dante’s Inferno in 1930s USA. Steve reflecting on the Original Art Edition of Art Young’s 1934 Inferno republished in 2020 by Fantagraphic Books, Seattle.

I feel strange about how and why I bought this book. I have a friend who loves graphic novels and I was keen to find a supplement for his birthday present. I saw this advertised before its availability in the UK and decided to buy it. I believed it was an example of an early graphic novel. However, although the work of a graphic artist it is clearly NOT a graphic novel (as I found on receiving my copy).

Nevertheless since I still am awaiting getting round to reading Dante’s The Divine Comedy in ‘the Italian’ alongside translations. The history of this want lies in my hero Alasdair Gray’s Dante project. If he can do it, why shouldn’t I, I thought, not giving a thought to the immense gap in our knowledge of world literature twixt he and me – Lol, such is life and such is the hubris one is capable of as a human being). Since setting this task for myself based on Gray’s example, Gray has unfortunately passed away and his Divine Comedy’s publication had to be completed posthumously.

And reading this book has stimulated me since Young intended it (as a fan of the Inferno, and of the illustrations of it in particular of Gustave Doré) as a means of showing that the themes of the poem had special reference to the Depression in 1930s America. This is the art of a committed socialist and reader of Karl Marx applied to an analysis of those events using the symbolic prism of a story of the realm of Satan.[1] Indeed so horrendous is capitalism, with its version of a ‘softer’ evil than that imaginable in the Middle Ages, Art Young has to imagine the Inferno as having been taken over by the arrogant bourgeoise. Art believed in ‘class struggle’. Charles Recht cites his response to a question from the United States Attorney when tried for sedition: ‘Mr. Young, do you believe in the theory of the class struggle’, with:

Mr. Barnes, do you believe in measles (Laughter. Pounding of the gavel by the Judge.)…

(sotto voce). You don’t have to believe in measles if you’ve got them.[2]

However, this work stayed in my collection as, for me, a monument of a bygone age and as one I am glad now to know. My intention to review it then has been replaced by a determination to pick two pieces of Art’s art and say why they matter when placed alongside his commentary. My comments are limited by the fact that I am not well qualified to speak of these matters at all, so this is very personal.

My choice of the two pieces is determined by two ideas fixed in my mind and character:

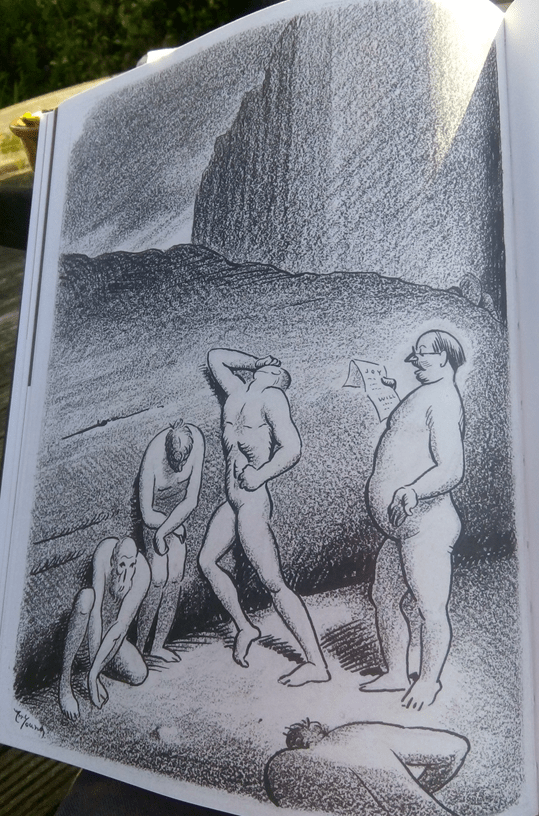

- The first graphic I chose has a history in my own thinking. As a social worker and social work teacher I became a great enemy of the phase in psychology known as positive psychology. Despite the intentions of its academic originators, this theoretical position in practice it was often used reductively as dogma – infernally I would say. Positive psychology could be parsed as saying that we, as fellow humans and / or professionals, can only assist people to embrace a life if we persuade them that life has value not in terms of assessing one’s relative access to resources – human, material, political, social and economic – but by how we perceive and assess our lot subjectively. This never quite hit the button when talking to people caring for a loved one (or worse once loved one to whom you retain a felt duty) without such resources, or continually being over-interpreted by the prejudices of an institution, as is the common experience of service users from a range of domains – most dramatically in mental health. It is the realm of ‘enforced cheerfulness’. Art Young’s graphic has the brilliant relevant title: Cheerupists.[3] It deals with a modern torment of the new Inferno run now as a successful business.

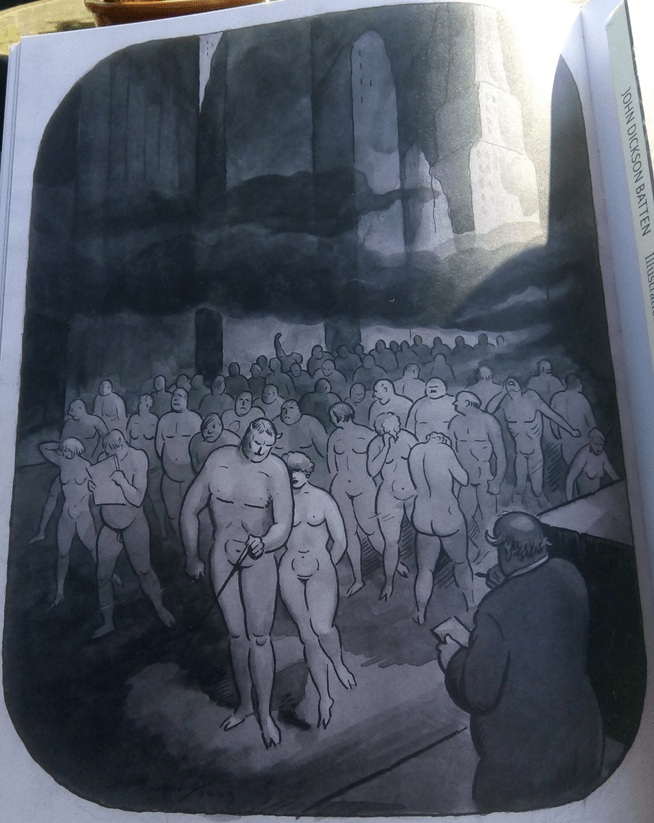

- The second was that romantic love finds a way irrespective of social arrangements and the mores of a society built on exchange values, such as Capitalism. The picture I chose is unhelpfully, given the subject I want to concentrate upon, called Looking At the Sinners[4]. This last section compares itself to Dante’s treatment of the sin of Lust through a type of romantic love: ‘That loving couple coming “which seems so light before the wind.” No, it is not Francesca and her Paolo’.[5]

Let’s take the first of these pictures:

A cheerupist can also be called ‘a sunburst’.[6] Like the ’positive psychology’ of today, although they consist of a group of people who think they are ‘individuals’, they are very like-minded, rejoicing reciting ‘poems of optimism and the power of the will’. The poem of choice will always be, Young tells us, that of the English Georgian poet W. E. Henley Invictus.

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

The poem seems designed for the infernal after all – with its ‘black pit from pole to pole’ and its willingness to serve any prevailing god. In fact these poets linked by Art to Henley identify with the lost and wretched only at a distance, seeing the goal of hope in their honorarium (money of course) and actually being themselves possessed of ‘incomes that protect them from the harshest impacts of these antagonistic surroundings’.[7] This is what fits them in my view for a Chair in Positive Psychology in today’s zombie universities.

Art Young shows the cheerupist as an overweight middle-aged and balding man, equipped with his reading glasses so that he need only see the hopeful words on the page and not the hopeless agony of the damned, the writhing of the wretched, the gestures of the lecture hall audience in our universities. They appear starved and do not hope to catch anyone’s eyes because their experience of marginalisation has been truly introjected. Instead they cling to a blank wall on which there is no writing or pictures but also no escape from The cheerupist’s determination to read out to them the reasons why they SHOULD feel cheerful. Can you imagine a worse torture?

In fact people, whether they be the unemployed of an economic Depression without adequate state aid or even otherwise degrading charity OR service users of poor social services OR just those accustomed to losing the game that that is stacked against them. As Young says, quoting an ‘old man’ to whom Henley’s Invictus is being read: ‘it takes more than determination to beat Hell’. Wasn’t Hell always thus? Isn’t this the essence of capitalism – citing equal opportunity but ensuring that there are no such equal opportunities, except for a symbolic few whose purpose is to justify the world as it is, not as it might be?

Another place you see these people is writhing from the effects of being ‘ran over’ by ‘a troop of Demon-police in automobiles’ both ‘body and soul for “obstructing traffic”.’[8] Of course the traffic being obstructed is the ‘traffic’ (or trade) in souls: eventually to become the key waste-product of Capitalism. What makes this picture so strong is the vey concreteness of the walls created by Young, hiding on the right a dark soul, almost hidden but peeping over the initial rampant unseen by either the damned or the cheerupist, but caught in the corner of the viewer’s eyes as they share a demonic laugh. Where is the light in this picture sourced? It appears to be that of a spotlight that frames the performance of cheering up, a false light if there ever was one.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds and shall find me unafraid.

That’s fine for you to say if you are already well-fed, provided with a role and impervious to seeing the true problem.

So on to the second picture:

First of all beware of this reproduction. I photographed my book outside on a sunny day and some light seems to flood into the picture from the top right illuminating something that looks like the Empire State Building as if divinely. This is an illusion entirely of my photography. The dark drawn by Young does not vary and anyway never reaches his naked sinners through a dark cloud positioned above them. Any shading on the buildings is purely relative to a general dull light that emphasises the progress of buildings into ruin.

It is a strange picture: the only one I have found in the book where any of the naked men in Young’s art possess a penis. But there is only one such example even in this picture, belonging to the man with his nose in the newspaper that makes it the easier for him to ignore the woman who walks with him, at a convenient distance apart. Art Young is the viewer and is represented (with horns) on the bottom right but his Paolo and Francesca are neither light nor swift like the wind like Dante’s. They are ‘outwardly mated, for parade only’. For lust is no more evident in Young’s take on Dante here than is love. Most of the women hide their eyes or look warily; both at Art Young avatar and us as viewers. The men are glum because they are ‘hurrying to nowhere’:

He struggled hard to get an education – graduated with honor. Now he just goes nowhere from force of habit. Because going somewhere has never got him a job’. [9]

See how Art paints that very learning on the faces – although their responses veer between open despair (in one man only) to glum depressed acceptance. One character at the back raises an arm as if in revolt. What is Art getting at here? He is showing some kind of hopeless moment of resistance before it is squashed by the effect on us as viewers of the other angry, sad or anxious faces. He paints this very sentiment:

Hundreds pass who feel inferior. If they could only feel that they are wanted, that someone believes in their ability. The word Inferno means: below, under, inferior.[10]

And this is true of artists ‘of literature, the drama, sculpture, and music’, he says. He draws himself holding a pen and not knowing where to start in representing such misery and illusory attempts to pass as a success but knowing that artists in such a Hell, though not in Dante’s, are unable to ‘make enough money to meet the problems of shelter, mating, and other natural desires of existence’.[11]

I hope this excursion through two pictures whets your appetite. It is a text full of delicious but cruel irony and pictures that often show more than, at first, you expected of them. I loved it. But sorry, Rob – not your thing at all. Wait till your 60th birthday, friend.

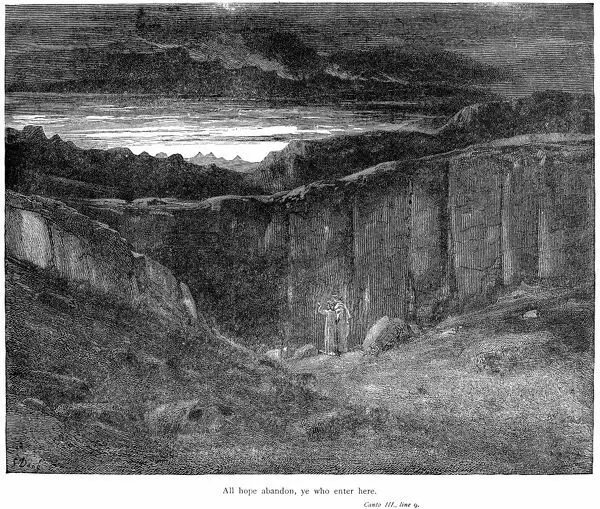

But it is good to know that some kinds of Hell welcome you without asking you to ‘Abandon Hope, all Ye Who Enter Here’, as in Dore’s take on this obscure opening into unhappiness which is cleverly shown going in the direction of dawn and hope but undermining this project at the same time. Clever old Dore’!

But you might wish you had had this warning given by Dante and other of his illustrators. But have any of us had that warning? In the grips of Capital and its inhumane values we all feel currently totally stuck and, my, doesn’t it make us seem small – as Art (in both senses of the name in this piece) shows below.

All the best

Steve

[1] See Charles Recht’s essay in Young (2020: xvii)

[2] Ibid: xix

[3] Ibid: 82 with commentary on p. 83.

[4] Ibid: 142 with commentary on pp. 143f.

[5] Ibid: 143

[6] Ibid: 83

[7] Ibid: 83

[8] Ibid: 83

[9] Ibid: 143.

[10] Ibid: 144

[11] Ibid: 144

One thought on “Graphic Reflections on Dante’s Inferno in 1930s USA. Steve reflecting on the Original Art Edition of Art Young’s 1934 ‘Inferno’ republished in 2020 by Fantagraphic Books, Seattle.”