‘… a time of demonstrations and counter-demonstrations, of angry bodies assembling in the streets’.[1] Reflecting on Olivia Laing (2021) Everybody: A Book about Freedom London, Picador [Pan Macmillan] – UK edition; New York & London, W.W. Norton & Company Ltd. – USA edition.

Sometimes the simplest ideas get neglected – like that holding Olivia Laing’s brilliant new book Everybody together. Everybody is a word based on aspiration to assemble together a diverse humanity. The basic unit forming ‘everybody’ is a the ‘body’. That latter term really is a metonymy for a person of course but persons need to be recognised as having little in common but that they possess bodies. Indeed each body, irrespective of other elements of the person, differs from each other body; being diverse too but for the basic template in which their variations occur. This variation passes well beyond the common diversities of differing ability (and the degree of support needed to enable that ability), race, ethnicity, sex/gender, choice of partner (including the option of no partner) in sexual or other liaisons, class and recognised status and so on. Assembling everybody together as one is perhaps impossibly difficult.

Yet a group assembled (whether containing ‘everybody’ or not) together is a body too – of a different type but labelled with the same token. And it is this basic ambiguity that Olivia Laing exploits in the brief noun-clause I cite in my title. For this book is essentially about, using the life and career of Wilhelm Reich as its basic guide, how individual bodies become the vehicles of anger, anxiety and a host other emotions (positive and negative). It is also about how and when they get to be assembled in larger bodies such that they also illustrate response to the processes which were common to all of them – such as socialisation in hierarchies and other oppressive institutional structures. It is this relation of both kinds of bodies that raise the issue of political freedom – and other freedoms (that often feel very personal but that are political when seen in the bigger picture).

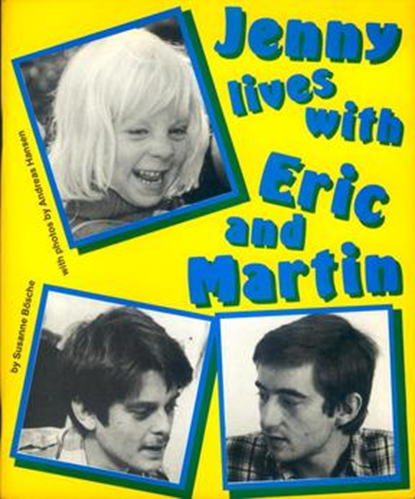

Indeed such issues often lie behind the fact that assembled bodies have very basic differences from each other, sometimes about different interpretations about freedom of choices about the body. This is why so often this book returns to political agitation in and around 1988 about Section 28 of The Local Government Act in the UK; a time I remember with similar anger and affection as Laing. This section of the Act criminalised the creation of positive images of queer people in books or other media available to children. The trigger to the division of the social body of a whole nation (Laing quotes the fact that statistics showed that 87% of people answered that they ‘thought homosexuality was mostly or always wrong’ in 1987) was the agitation promoted by the Thatcher Government against an anodyne book by a Danish author, Susanne Bösche. The book literally just showed a weekend in the lives of a male gay couple and their daughter: its title was Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin.

The quotation cited in my title refers not to the agitation of this period however but to the ‘inter-war years in Austria’ and forms part of the telling – which occurs over the course of the book – of the life of Wilhelm Reich, whose embodied thinking is so central to this book. Before moving on I need perhaps to justify my term ‘embodied thinking’,.

This term attempts to encapsulate the thought that no cognition (no thinking or its equivalents and components like perception and memory) take place outside a body, whether that body be that of an individual or group, and that such thinking is determined by the history of that body, including its regulation by self or others. Laing continually revisits times in her own life as well as those of others that can be described in similar ways to those ‘inter-war years’, including times in which she was heavily involved in contributing as one ‘angry body’ amongst others as part of the internal ‘assembly’ of ‘angry bodies’ that constitute a social politics or their configurations of alliance and opposition in wider society. An example of this would be the Gay Pride rallies against Section 28, for Laing had (like the fictional Jenny) been brought up in a queer household and defended it with pride. It was a pride in her lesbian mother that allied itself to her knowledge that she could be most accurately defined as ‘non-binary, even if I didn’t know the term yet’.[2]

Another such time was the environmental protests at Newbury in 1997 where there were ‘maybe a thousand people there, scrambling on diggers and shinning up cranes’.[3] It is in these contexts that we discover that a basic division of crowds includes ‘angry bodies’ (often angry with each other) which she explicates through Elias Canetti’s Crowds and Power. However she also uses concepts of how oppositional issues are conceived politically social bodies devised in Stefan Jonsson’s Crowds and Democracy. The latter uses the terms ‘swarm’ and ‘blocks’ which set against each other respectively: ‘a mass not yet dammed up and disciplined’ and ‘an armoured mass, drilled and disciplined, violently cut to shape in order to fit the representative units of the soldier, the army, the race, the nation’.[4]

It is symptomatic of Laing (and not just in this one of her great books) however that, in using thinkers like Elias Canetti, Laing embodies their significant books in the writer’s life experience quite as brilliantly as is done with her own life here – and brilliantly as she does that of her own. This applies in spades to the confrontations with the embodied thinking in the lives, and manner of confronting their deaths, in Susan Sontag, Andrea Dworkin and Kathy Acker.[5] Because individual bodies – that of everybody – are too full of angry conflict and here she finds Reich so much more useful than Sigmund Freud, who lay down his own body (and that of his daughter, Anna) in this respect for the preservation of a group body he called the Psychoanalytic Movement. The relationship of bodies ‘violently cut to shape’ in Jonsson’s notion of the block emerges in the various ‘knots’ and hard tense blockages so hard to remove from even a single human body as Laing discovered in her degree, and subsequent career as a practitioner In Hove, of ‘herbal medicine’.[6] Nowhere is this better plotted than in consideration of the contrasts and comparisons of the life of the bodies named Andrea Dworkin and Angela Carter and how these contrasts are reflected in their readings of the Marquis de Sade.[7]

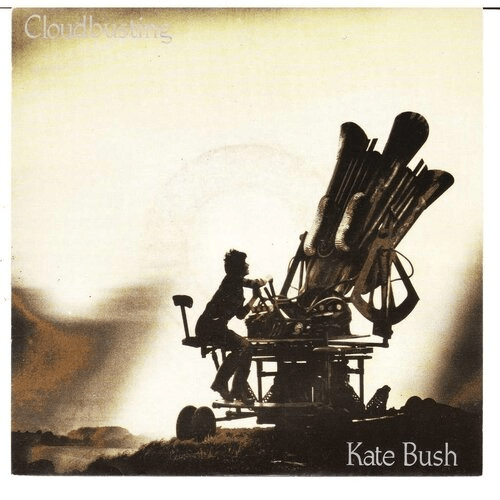

Amongst thinkers about the genesis of her embodied thinking the lead figure is Reich. He helps her show through her own biography that, whether in love with a man or woman or a body that identifies in non-binary ways, being raised in a heteronormative and queer hating society enables her to ‘feel the legacy of that period in my own body, as knots of shame and fear and rage that were difficult to express, let alone dissolve’.[8] Now some very peculiar thinkers have tended to oversimplify the relation of body to ‘dis-ease’ (the opposite of ‘ease’) so that it’s amelioration is the equivalent of curing disease in the medical model – simplistic (but rich) popularisers like Louise Hay for instance. And this book shows how angry one can become about these dangerous merchants of positive psychology. Reich too though could oversimplify and to assert some arrant nonsense behind his invention of the ‘liberation machine’ as is continually stressed in his appearance with his (played By Bush) in Kate Bush lyrics of her song ‘Cloudbusting’.

In the USA edition of her book, at least in the first edition I have, this idea is reinforced in the use of a single photograph of that ‘orgone accumulator’ device (in its form as an ‘orgone box’ in which the stressed patient sits) as used to treat individuals. It must have seemed a good idea to Laing and to the publishers to reproduce that photograph 8 times (once for each chapter before the chapter title) but with each photograph being covered by increasing darkness encroaching on the print from the viewer’s right (probably deliberately the right given Reich’s imprisonment in America being one as one of the atrocities of McCarthyism). See my poor reproductions below to get a rough idea of that sequence. Unfortunately the production values of the USA edition make the effect hard to see anyway and it is dropped (at least as a sequence) from the more elegant UK edition. But it is a very interesting idea and made me pleased I contacted this edition first.

Laing never shies from controversy and personally I love her the more for her spirited and angry rejection of the current tsunami of intolerant transphobic hatred in some versions of a thing that calls itself modern feminism. She rightly insists on self-identification as a principle, saying:

You can hate what happens to bodies categorised as female whilst also remaining sceptical of the notion of two rigidly opposed genders, coloured pink and blue. Even Andrea Dworkin understood that.[9]

Of course the adjectival sub-clause ‘coloured pink and blue’ is not fair since radical feminists who are also transphobes believe that sex need not include socialised gender symbols but I sort of agree with the anger that produces that simplification in the interests of showing your point more forcefully. In the end, it is slightly worse to make the rigidity hang around biological markers and functions like having a penis or not (whether as practiced functions or not), since these vary immensely anyway. It is like that moment when after showing how the embodied thinking of Magnus Hirschfield entered into that of Christopher Isherwood she says; ‘Imagine telling J.K. Rowling that’. What is it that we can’t say to J.K. Rowling without, like Stephen King, being ‘cancelled’? It is the fact that: ‘the line between male and female, straight and gay was decidedly blurred’.[10] Isn’t that just truth – even truth in contemporary biology as Anne Fausto-Sterling keeps repeating.

I think this book joins the other tremendous explorations of life outside the norms by Laing, including her novel Crudo (see my old blog) that prove that without such lives we are the poorer.

All the best

Steve

[1] Laing (2021:251f.) Page references are to the USA edition, although in some I have checked in the UK edition are the same. This one is for instance. The quotation refers to the ‘inter-war years in Austria’ but Laing continually revisits times that can be described in similar ways, including times in which she was heavily involved in contributing as one body amongst others into an ‘assembly’ of such ‘angry bodies’.

[2] Citation in ibid: 284

[3] Ibid: 261f.

[4] Stefan Jonsson cited ibid: 263

[5] Ibid 36ff, 119ff. and 48ff. respectively and elsewhere

[6] Ibid: 20ff.

[7] Ibid: 119ff, For Dworkin on de Sade 126, Dor Cater on De Sade 131.

[8] Ibid: 5

[9] Ibid: 285

[10] Ibid: 70-79 (citation on p. 79)