Note: Revised 25th June. I am inclined to think better of this piece now.

‘… instead lean over the mouth of a sewer, convincing yourself you are breathing in a flowerbed’;[1] ‘the swiftness of flight without the materiality of the wings … without incarnating it in a body’.[2] Reflecting on Marcel Proust (translated by Charlotte Mandell) (2021) The Mysterious Correspondent: New Stories London, Oneworld Publications.

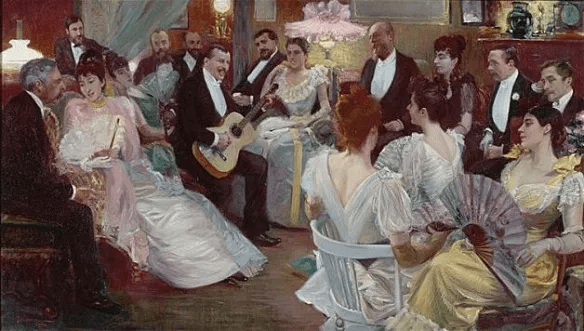

Looking at that beautiful young man on the cover of this new publication one would have thought that this book would recall the charm of falling in love with him in a Paris salon and finding him surprisingly receptive to our desires. Instead the actuality of hot, damp, and possibly fetid, air is what escapes from the stuffy rooms of Parisian high society at the time of Proust. Not that the pictures of that time don’t always contain a sensuous frisson of textures and an air of perfumes that linger; brushed from ladies with large fans. Because they are a in a picture we are forbidden to touch: moreover it might disappoint it if we could. Look for instance at the lovely scene caught in a passing instant of a Paris salon in 1891 by Jeanniot below. Light lingers in lieu of touch on textured surfaces from which the fingers slip.

There is, as I see it, a rather strange double perspective in this painting, which views the scene from above but also seeks to look up from the floor space to follow certain diagonals upwards. The figures clothed in sombre blacks on the viewer’s right form a slight upward tilting line that mirrors on the viewer’s left the diagonal line of gaze formed by the reflection of a superior light source on the white silk dress of the lady in the armchair towards the lamp behind. The lamp is almost dulled by the reflected sheen in her dress. It is as if viewer were allowed, though standing, to abase themselves to sit at the feet of this avatar of the Duchesse de Guermantes. This is Madeleine Lemaire, The ‘Empress of the Roses’ of Robert de Montesquoi, himself the main target of Proust’s character (the Baron de Charlus). Lemaire was a visual artist too as well as a social fixer who made the introduction of Proust himself to bohemian high society.

But I think the abasement of the self is much more a part of the Belle Époque than we usually think; it is, perhaps, a part of any rigidly demarcated class society in which hierarchy interprets every sensation, emotion or thought that we experience – or nearly every such experience for nearly all people. Proust is a fine and sensitive meter of such experiences.

Mandell struggles in her introduction to this brilliant and too-brief collection to exactly state if these stories focus, and if so to what degree, on queer lives, or as she annoyingly has it, ‘homosexual psychology’: ‘homosexual psychology, or homosexuality seen from within, whether directly or transposed, does not even remotely constitute the sole concern of these stories’.[3] Well, so far, so unclear. If the very nature of queer desire can be thus so easily ripped from its context, even in literary criticism, can we really see how it was located in any psychosocial variant through history? I would say we can’t because ‘homosexual psychology’, seen as a distinct phenomenon even if we don’t label it, and we pretend that it is just the way someone currently engaging in a homosexual performance (in solitude with the imagination or with others) in private or public thinks and feels about the world for that particular moment.

This is not how it works in Proust, where the materiality of encounters, especially queer encounters, is heavily stressed – in terms of setting, objects and properties and bodies. Of course Mandell is not alone in her views. Sarah Boxer writes, with regard to the ‘queerest’ of the volumes of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time now translated as Sodom and Gomorrah, that it ‘thrilled Colette: “No one in the world has written pages such as these on homosexuals, no one!”[4] But this was the writing of a very mature, if continually guarded and masked literary master.

Moreover Mandell, in her introduction to the stories is correct to compare these early Proust stories to André Gide rather than to Proust’s own mature writing to show how narrow is his insistence as a young man, and at the time of these stories, that homosexuality was ‘a curse and cause of much suffering’. It is this perspective that is still easy to pick up from the translations from Proust’s own biography in the life, loves and actions of his narrator, Marcel, with his own independent but unhealthy fascination in other people’s queer sex lives. Such intertest extends to frequent voyeurism. Meanwhile Marcel elaborates his own heterosexuality by transposing gender of the loved ones taken from Proust’s own life from men to young girls. There is nothing like Gide’s value system in Proust wherein the discovery of a vital love between queer men can be valued by ’the paths it opens, the barriers it removes, by the weapons it provides’.[5]

Yet if we read In Search of Lost Time (or Remembrance of Things Past as it was when I read it in fading second hand Chatto and Windus volumes in 1973 or so) and you are still ‘dealing with’, as they used to say, your own sexual identification or identifications, it offers no clear paths into that subject. Not least because to get to the heart of what constitutes love and sexual desire and the cusp between them, if one exists, in Proust is too confront too many topics in which one feels also at sea. These include the nature of the things that make up what we understand by objects of sexual interest, regardless of other interpretations and evaluations of them. But more of that later. In these early stories there is just a painful negation constituted by a ‘taste’ in sex with men (for that is how it is seen) that might have been better if never developed, especially as his queer characters age so painfully.

In what follows I want to go on a long meander around this extract from In The Underworld, which Mandell says is an extract from ‘a discarded play’ in which the homosexuality of the fictional aristocrat Quélus is discussed in passing first by the biblical Samson (who is vaguely sympathetic given his experience of Delilah) and the theologian, Ernest Renan. The latter is rather bemused that anyone should, in these latter days, need to have sex with anyone other than women since all love since Socrates’ day has become a sickness, he says but one which opulent women alone can raise to a ‘sublime disease’. This rather tortured and eccentric symposium contains this passage spoken by ‘Renan’ to Quélus. It follows his comparison of homosexuality to albuminuria, a consequence of kidney disease in which the albumin protein content of the urine is overly elevated, and which had had its effects on many of Proust’s family. Renan’s refusal to ‘absolve’ Quélus smacks of the temporising of one whose moral compass wavers with the times:

…, the thought of absolving you, my dear friend, is far from me. … life is rather a game of skill. It is not very good, from any point of view, to take one’s pleasure by stroking against the nap. A man who being endowed [with] the most usual configuration of the palate would, however, take on the habit of finding the most exquisite treat to devour from excrement would be received with difficulty, at least in good society. Certain repulsions are stronger than anything and are given a mark of infamy. Inevitably our disgust and our esteem could not go to the same people. And yet who would dare to say that disgust is not eminently relative?

The most exquisite fruits are within your reach, it is imprudent to pass them up. Why turn away from the most exquisite perfumes offered you and instead lean over the mouth of a sewer, convincing yourself that you are breathing in a flowerbed. ….[6]

It is useful to use Mandell’s footnote restorations of Proust’s drafting (which I restore to the text above) to see how the recursive flow of ideas allows Proust to change metaphor here from presenting sex as a ‘fruit’ (a deeply conventional and religiously associated idea) to that of a perfume, thus symbolising the gendered nature of the sexual choices with which Renan feels modern life faces us. There is nothing moral about Renan’s discourse, as given by Proust. It is all rather a matter of smell, taste and the limits of what other people will bear to see in our public behaviour. At its heart is the contradiction between seeing sexual choice as a matter mediated by either ‘disgust’ or ‘esteem’ that barely acknowledges that it matters whether that that is a choice of true antinomies or a matter that is ‘eminently relative’?

And this game Proust will continue to play through his career, turning from a focus on Quélus here, who barely gets invented, to the career of Monsieur (and later Baron) de Charlus. Is there a sound relation to Quélus in the name Charlus I wonder? Indeed many of these debates are taken up as contemporaneous to Belle Époque realities (if it had any) in Book 7 of In Search of Lost Time and thereafter, as the novel dives with Charlus into the queer underworld of Paris male-brothels and the hint in The Prisoner of the ubiquity of the public male urinal in Charlus’ life.

It is then at this point I want to return to ask you to imagine how I read In Search of Lost Time (Remembrance of Things Past then remember) or indeed how any young person inherits and learns how to handle queer sexuality as identity or secret. We do not need Freud to know that the body itself offers enough of these urgencies for us to find that we encounter our sensual selves diversely, but also – through education and training – selectively. The body given by our biology is hardly a clear guide to our choices whether we experience it in a state of polymorphous perversity, rigid genital specialisation or any other state of libidinal cathexis between these poles provided by the instincts and imagination in concert. We become dependent on navigating between socialised responses of both disgust and esteem about certain bodily sites of legendary capability of sexual stimulation, whether they be aetiologically instinctual, acquired or a mix of both. But even without the selection (preselected, chosen in the moment or developed by practice as our olfaction might be) of erogenous sites of the body in the penis, vagina, anus, nipples, skin surface in a part of whole of the body – such as the feet for some people) sexuality veers outwards to occupy those choices with one eye on how those choices appear to others.[7]

But the occupation of different and diverse body parts – some of which have about them a debate of disgust set against esteem – just like that Proust makes Renan articulate. Sexual feeling can occupy also items used by the body or worn upon it (even invisible ones like perfumes), whether they bear the marks or stain of the body – in sweat for instance – or not. And sex is not just a matter of bodily opening and orifices or those of clothes or decoration, it can apply to places as Renan hints by calling the choices of object of desire, at a point where hardly any relativism between disgust and esteem is on show, as either a ‘sewer’ or ‘flowerbed’.

Whilst sewers had a defined place in Haussmann’s Paris, Proust’s novels evoke settings which can be transformed by the imagination or even the words we use, just as is the case in real life. The reverse is true as well, as shown in the literary critical interest in tea-taking in In Search of Lost Time. When I was younger homosexual there was a prevailing frequency, traceable to the fact that only the strictest definitions of privacy in the 1967 Sexual Offences Act enabled legally esteemed queer sex legal, of using, as a venue for gay sexual encounters, the public toilet. It could be known variously in sanitised and homely words like ‘cottage’ or ‘tea room’ (the latter more in the USA when in English). In Paris, it was the same, if not more so and in the 1930s and beyond English bohemian who were queer would satisfy – as did David Gascoyne breaking off from a tea engagement with his then fiancé – their sexual taste for men in Parisian urinals.[8] Jarrod Hayes opened up the question of the importance of the common use of the word ‘tasse’ to describe male French urinals in 1995.[9] But in 2017 his suggestions were opened up in Eels’ comprehensive reading of the novel in which the dominant image of the novel of Marcel, dipping a madeleine into a cup of tea, will never look so much a matter of French social esteem awarded to English custom again.[10]

Even as a young man, I remember the terrible fuss when Jacques Chirac, as Mayor of Paris, in 1981 replaced the ornate fantasies (‘ironic imperial-Roman grandeur’ in Andrew Ayers description) that describe some (if very definitely not all) examples of the Paris ‘vespassienne; or, in plainer French, a pissoir; or, in yet plainer French, a pissotière, or; in the plainest of English, a cast-iron street urinal’.[11] The very finest were romanticised in beautiful photographs by Brassai, such as that used in the Ayers article, or that fine selection given by this link to MessyNessychic. These venues are used, almost in an aside in a section of The Prisoner in which a lower class butler’s malapropisms are used to expose the daily activities – apart from dinner and tea at the houses of ‘good families’ – of the Baron de Charlus, here noticed by his choice of very light trousers which would show under the raised cast-iron walls of any street vespassienne. These raised cast-iron walls might be seen even in the following examples from an article by Neil Patrick online:

M. de Charlus was in the habit of wearing …. very light trousers which were recognisable a mile off. Now our butler, who thought the word pissotière (…) was really pistière …. Constantly the butler would say: “ I’m sure M le Baron Charlus must have caught a disease to stand about as long as he does in a pistière. That’s what comes of running after girls at his age. … As I passed the pistière in the Rue de Bourgogne I saw M. le Baron de Charlus go in. When I came back from Neilly, quite an hour later, I saw his yellow trousers in the same pistière, in the same place, in the middle stall where he always goes so that people can’t see him.” …[12]

Lest we stray too far from a focus to my largely unfocused reflections, it’s worth remembering that this humorous and embarrassing episode from the novel is really about how the Baron’s obsession with good society and refined taste is here placed in a context where the butler can speak openly of acquiring a sexual disease from ‘girls’. It is only by suppressing any knowledge in the ‘general’ population that this is an unknowing description of frequent queer sexual encounters made by Charlus that makes this possible. The distance between the smell of the sewer and the flowerbed is again evoked but now from a distance provided by social comedy. It is typical of later Proust. But it is also very much about the ways in which Proust negotiates sexuality through associations with places and objects of esteem or disgust, and sometimes suggests the relativity of response possible as mentioned if not practiced by his version of Ernest Renan.

And in other stories in this collection it is clear that Proust long experimented with the problems of the admixture of social and what feels like very personal (even private) disgust with exploration of the limits someone might go to to satisfy their desire. In this later cases it involves imagining the fetishist’s take on a particular body part or accoutrement of dress that might fulfil their desire. It is this honesty before the fragmentation of the desired body that is the triumph of Proust’s art, so precisely does it capture the feel of viscerally sensual longing and its attachments wo objects which cause in some a mix of shame, guilt (and even disgust) simultaneous to desire.

For him this was the way to progress from myths of our ‘true nature’ to proper awareness of the role in such desire of an intervening ‘pose, or a mask’ and a situation in which ‘a part of her life that she hid from me was in fact her true nature’, as he says of a lady who masks the fact that she is dying from a cancer from him. She feels clearly that the sordid fact of death, since it involves the body primarily, soils the ‘esteem’ in which she continues to want to be held by ‘good society’.[13] The debate here, as with the nature of disgust is that between the concept of ‘nature’ and the effects of social pressures – conscious (as here) or unconscious – on the person.

This is best handled in the eponymous story in this collection which concerns a letter received by Francoise, the central point of view in this story, in which possession of her body is desired by an anonymous correspondent (hence The Mysterious Correspondent). The letter labours the point: ‘It is your body that I want‘ – even tracing desire down to an act performed on one part of it by another singular part of the other’s body (‘lift the corner of your lips with my mouth’) that is presented as if a fetish. Despite the wet concreteness of the bodily detail, Francoise ‘read it in a dream, in the shifting, uncertain gleam of the flames’. The metaphor in the prose is both infernal and dreamlike and yet based on experiencing a real household fire in a real room. Her continual rejection of the correspondent is like the denial of nourishment, because of her virtue’. But she does dream of that nourishment with the kind of detail that feels like pressure on the senses at the surface of her skin. She imagines’ her correspondent ‘a soldier’ (hopefully somewhat more convincing one than the young Proust himself – see below):

… one of those soldiers whose broad belt takes long to unbuckle,

artillerymen(or)chasseursdragoons who let their swords drag behind them in the evening at street corners while they look elsewhere and when you clasp them too close on a sofa you risk pricking your legs with their big spurs, soldiers who hide all beneath a too-rough cloth …

This is hardly the ‘interior life’ of the respectable and virtuous wife Francoise wants to appear but the irony of the story is that the reader knows, as Francoise thinks she does not (or does she), that the correspondent is actually her closest female friend, Christiane, who is dying of ‘a wasting disease’. This possibility is not even entertained by Francoise in her secret dreams (whereas the slow undressing of a male lover does) and must remain entirely implicit in the story. What game does this story then play? On the one hand it unmasks Francoise and shows that her interior and imaginative life is more open to the sensations of the body that she will allow to appear on the surface. On the other hand, it shows that there are sensual dreams that are not even admitted to exist in private moments to herself, at least not in a way that can be articulated by any storyteller explicitly, even herself.

These are the secret stories which negotiate the repulsion and disgust rather than mere disapproval of good society – like the effect of Mlle Vinteuil’s open lesbian alliance after the death of her father does in the party held by the Verdurins in The Prisoner. Another possibility is that the story utilises the unsaid to release the body of the beloved and the desire for it into the void, where nothing ends because nothing ever really starts except in the imagination. The fetishization of a soldier’s too-rough cloth is almost too material. Proust’s early fascination with mysterious people who wake one’s bodily desire without fulfilling it is also the story of Pauline de S and Christiane. They die from being denied the body (perhaps) and thus live a richer life because the body never lets them down by aging or incapability to match its sensual imagination. Proust’s description of Beethoven’s Eight Symphony is precisely of this order but makes it much clearer that imaginative art offers what bodily love could, at least momentarily, but unlike things of the body does not soften or fade with age and habitual use, get bored or, worse, begin to bore me.

the beauty of a woman, the friendliness or uniqueness of a man, the generosity of circumstances

murmur to us, in an indistinct voice, promising us grace.[14]

Now this sentence plays all kinds of games with gender. Presumably the part crossed out is crossed out because it compromises the masculinity of the man whose different qualities are equated with those of a woman’s ‘beauty’ without denying there is an equivalence of gratification on offer. But it also plays games with religious language such that which, once embodied, creates promises to us in the indistinct voices. It is only a symbolic grace and has much of the body lingering in its incense. It is something like the grace of God but it is unlikely to last as long as that does in myths. This play with qualities that change but do not come to an end continually measures unfaithful lovers, or our loss of faith in, or love for, them against that which changes without getting exhausted (in both senses of the word ‘exhausted’). Because the love of art stays with us and cannot tire us because it only feels like it calls forth our bodily response, it does not do so, and hence does not require anything like consummation.

A

worldkingdom of this world where God willed that grace would keep the promises it made us, came down so far as to play with our dream, and lifted it to direct it, lending it Its form and giving it Its joy, changing and not elusive, but rather growing and varied by possession itself, a kingdom where a gaze of our desire immediately gives us a smile of beauty, … , where one feels without movement the vertigo of swiftness without thedangerweariness or exhaustion of struggle, without danger the intoxication ofswimmingsliding, leaping, flying, where at any moment force is matched by will, desire with voluptuousness, where all things rush out every instant to serve our fantasy and fill it without wearying it, ….[15]

That the games that lovers play are here reproduced without consequences to any body involved does not guarantee that this satisfaction is not still of the body. Rather it makes the body a matter of grace and spirit – not vulnerability and exhaustion – experiences that bodies tend to eventually decline into either from incapacity or the boredom of satiation. This is shown at its best in Charlus in The Prisoner, whom had ‘reached the stage when the monotony of the pleasures that his vice has to offer became wearying’.[16] It makes sense that Proust’s art raises the fear of exhaustion and mortality but also delicious expectations of both consummation and ending by putting any stasis in that love to flight. Art ensures it is totally a matter of the imagination. The whole meaning of Odette to Swann and Albertine to Marcel lies in the ‘sweet cheat’ being eventually gone, so that the art of the book itself can fill its place. ‘Albertine disparue’ is clearly preferable to an Odette that stays to pall our taste in all we once found sweet and fragrant.

Now the belief that multiple simultaneous lovers lost forever to the person who called them forth and to each other in evitable lapses of their, or our, faith in the longevity of love, and their continual succession by new variants is central to Proust. The final extract in this book tells, in its final paragraph, of the genesis of queer men as a product of God’s indifference: ‘So He set desirable creatures before him and advised infidelity’. This is also central to the way queer love became to be theorised as a thing apart. Faithlessness is necessary not because of a belief in the need for continual change but in the service of maintaining a belief in something that does not change – our ability to respond as a body without the body being subject to imprisonment in itself, a body that we only sense, know, feel and think in itself alone and in the substitutive achievements of art, even art that continually, like God, ‘came down so far as to play with our dream’. In some manifestations it reduced to quantification as in John Rechy’s novel, Numbers.

My own feeling is that herein lay the rot that elevated the heroic but ever isolated ‘homosexual’ through both suffering and resilience and then promoted this image, despite the availability of other images – ones that had potential connection to others including other queer people. There were such images in Gide for instance. Proust’s ‘bad faith’ that praised infidelity to the person, in favour of the sensation that a succession of numerous persons offered you in sequence was honoured by history in both self-hating queer people and people who hated queer people for any number of reasons. The queer body was equated with that state of need that could not accept either aging or death and trapped in a narcissism that only a parade of night after night sameness (or art with its claim to transcendence) could fulfil. This is a body so abstract it exists in a continual orgasm that seems perpetually the very first that body has experienced.

For if our body could enjoy this, the play of its spirits would have to be incarnated, but in a subtle body, without size and without colour, at once very far from and very close to us, which gives us, in the deepest part of ourselves. The sensation of its freshness without there being any temperature, of its colour without it being visible, of its presence without it occupying any space. Withdrawn from all the conditions of life, it would have to be as swift and precise as a second of time; nothing should retard its momentum, prevent its grace, weigh down its sigh, stifle its moan.

The body is abstracted into one long delayed sequence of non-consummated consummations and that point where body and person meet is never reached (or if reached rapidly retreated from) in favour of the desire of the imagined body never possessed or lost. But it is the generality of a recurrent symbol – the fort-da of a recurring bumping into and not engaging. For engagement becomes an anathema. Rather the endless repeated variations of delayed expectation for a repeated end stop whose function is to announce the next one coming up. Art in one exquisite sentence after another exquisite sentence than anything like commitment to meaning for its own sake, even for a second.

The notion of a sexuality devoid of such materiality, often under the disguise of lovers’ discourses about their love, are scattered through Western culture. In these binary distinctions there is often an attempt to regulate behaviours and discourse about behaviours in ways that divide love from physical sex, soul (or spirit) from body (or body from mind in more atheistic formulations), the sacred from the profane, the pleasing from the disgusting and, finally, the world of subjective thought and feeling from that of material objects. These distinctions emerge historically in the languages of religion and theology but by the end of the nineteenth century they find a home in theories of the arts and aesthetic pleasure, such that Walter Pater in the UK can talk of art, in his 1873 Studies in the History of the Renaissance, in these terms:

To burn always with this hard, gemlike flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life. . . . While all melts under our feet, we may well catch at any exquisite passion, or any contribution to knowledge that seems by a lifted horizon to set the spirit free for a moment, or any stirring of the senses, strange dyes, strange colours, and curious odours, or work of the artist’s hands, or the face of one’s friend. . . . [17]

This is a strange, indeed a queer, kind of bodily stimulation appealing to the senses and sensual experience but incapable of the kind of variation that brings things to a conclusion and therefore an ‘end’ rather than carrying on perpetually – always ‘hard’ and ‘gemlike’ this kind of burning is not simultaneously an act of destruction and/or withering into something limp.

All the best

Steve

[1] Ibid: 98

[2] Proust (translated Charlotte Mandel) (2021:74)

[3] Ibid: 15

[4] Sarah Boxer (2016) ‘Reading Proust on My Cellphone’ in The Atlantic (online) [June 2016 issue] Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/06/reading-proust-on-my-cellphone/480723/

[5] André Gide [trans Richard Howard 1985:75) ‘Third Dialogue’ of Corydon London, Gay Men’s Press.

[6] Proust op. cit. (2021: 97f.)

[7] I chose the word ‘occupy’ on purpose. As Peter Gay once reminded us it is a better that word (and more like Freud’s word Besetzung) than James Strachey’s cathexis since it imagines the actions of an army or nation state. How much better even is the French preference for ‘investment’ as a translation of the same German word that Strachey’s abstract classism – investissement).

[8] Gascoyne biography p.

[9] Jarrod Hayes (1995) ‘Proust in the Tearoom’ in PMLA, Vol. 110, No. 5 (Oct.,1995), pp. 992-1005 (14 pages) Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/463025

[10] Emily Eells (2017) Proust’s Cup of Tea: Homoeroticism and Victorian Culture Routledge, 2 Mar 2017 – 248 pages More at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=xVVBDgAAQBAJ&pg=PP40&lpg=PP40&dq=jarrod+hayes+tea&source=bl&ots=lWCbb2DIBe&sig=ACfU3U0kBRaEx1lrWTkD3g7ZpFcjjdSLUA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj77pKt7KjxAhXUoVwKHTbiCPgQ6AEwEnoECBEQAw#v=onepage&q=jarrod%20hayes%20tea&f=false

[11] Andrew Ayers (2009/10) ‘Street Relief: The Unique Story of Paris’ Public Urinals’in Pin-Up Magazine 7 (Fall/Winter 2009/10) (online) Available at: https://pinupmagazine.org/articles/the-last-vespasienne-street-urinal-essay

[12] Proust, M. (trans. C.K. Scott Moncrieff and Stephen Hudson) [2016: c. Loc. 37997] In Search of Lost time – Complete 7 book Collection (modern Classics Series) Kindle,e-artnow, info@e-artnow.org Available on Amazon at 49 pence currently.

[13] The story is ‘Pauline de S,’(pages 25 – 32). Cited section is in Proust (trans. Mandell) op. cit. (2021: 32)

[14] Proust (2021: 105) In quoting the book I include sections crossed out by Proust, but which Mantell gives us in a footnote, in the original trick but crossed through thus: murmur to us, in an indistinct voice.

[15] Ibid: 106f.

[16] Proust (2016: c. Location 2262).

[17] Walter Horatio Pater. Available from: https://victorianweb.org/authors/pater/renaissance/conclusion.html