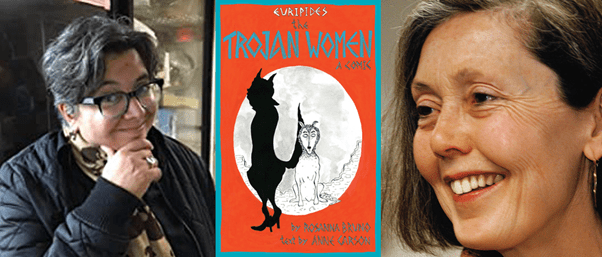

‘WE HOLD CERTAIN ELEMENTS IN TENSION’.[1] Making a ‘comic’ out of a ‘tragedy’: drawing from inexplicable pain and blaming? Struggling to critique but thoroughly loving Rosanna Bruno with text by Anne Carson (2021) Euripides, the Trojan Women: A Comic Hexham, Bloodaxe Books

For another blog on versions of the story of Troy in the work of Anne Carson see my blog: ““Says he can’t believe how much I look like her.” (εϊδωλον): Reflecting on Anne Carson’s (2019) ‘Norma Jeane Baker of Troy’ London, Oberon Books”. Available at: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2020/06/24/says-he-cant-believe-how-much-i-look-like-her-%ce%b5%cf%8a%ce%b4%cf%89%ce%bb%ce%bf%ce%bd-reflecting-on-anne-carsons-2019-norma-jeane-baker-of-troy-london-ob/

Let’s start with the critics! Edith Hall is probably one of my favourite academics in that she has long worked actively for the importance of her subject (Greek history and culture) outside of the academy as well as within it. She is a foremost champion of a politicised use of the form and content of the art of the Ancient Western civilizations, especially that of Greece. It is shown in her critical work on the poetry of Tony Harrison but also in the study of alternative and marginalised learning amongst the working classes about those ancient civilizations and their politics and literature. In a contexts where elite classes see the classics as their own singular possession (as exampled in her participation in debate on Boris Johnson reciting by heart the opening of the Iliad), she takes a radical perspective on how and why this need not be the case forever. I tried to show why in a past blog.

However, I start with Hall’s review of Carson and Bruno’s new ‘comic’ (in the sense of graphic art) version of The Trojan Women in The Times Literary Supplement (TLS) because it focuses on her many stated reasons why such a play might not be suitable for this medium. She does not fully endorse such a move, at least, as I read both content and tone of her piece. Hall starts by wondering whether it is the ‘monumental standing’ of this play as an examination of the consequences – especially to women and children of wars fought entirely in the interests and in the styles of men – that makes the decision on graphic art or the comic as a medium problematic. She also finds other problems: the ‘abstruse references’ favoured, as Hall sees it, by Carson as a poet and generic innovator and the handling of the appearance of text in ‘upper-case handwriting’. The latter is said to create ‘effects ranging from crazed diary entries to red-top headlines’. In the end though, it is not these flatter features of what is clearly seen as a rather modish contemporaneity but its ‘monumental standing’. Later on she renames the latter quality in reference to the plays ‘metaphysical profundity’, that, rightly I think, Hall argues to be centred on the character of the aged queen of Troy, Hekabe. Lets be clear whom the latter is. She is the wife of Priam, last king of Troy, known (of course) as Hecuba in various other places including Hamlet, where her loyalties to the values of her dead husband, Priam, contrast so much with Queen Gertrude, the young Hamlet’s mother to old Hamlet, poisoned by her new husband. It is Hekabe who is monumental in the play:

Of all Greek tragic figures, Hekabe confronts most directly the philosophical problem of unearned suffering, in the extreme forms of genocide, separation from offspring, bereavement, enslavement, rape and absolute annihilation of the physical homeland and social bonds. …[2]

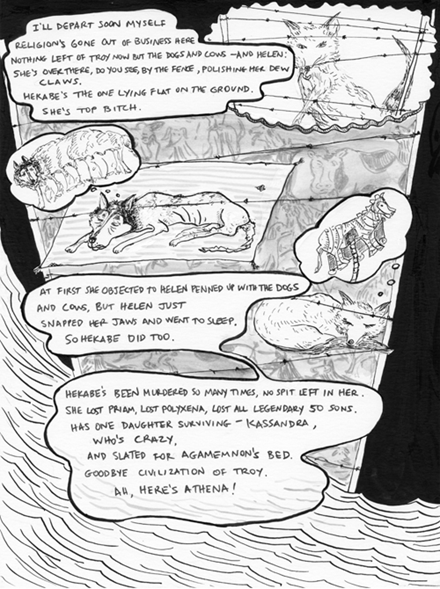

In the end I think Hall believes that Bruno and Carson do capture some of that quality in the noble queen in the ‘top bitch’ dog to whom the latter transform that character. She is introduced to us, as in the play by Poseidon, the God of the Sea (he first appears ‘a large volume of water measuring 600 clear cubic feet’) acting as prologue. To him, she forms part of the reason He is leaving leaving Troy himself because ‘religion’s gone out of business here’.

Hall is won over precisely by the way in which Bruno and Carson home in on the existential problem of the play – its brutal honesty (which I prefer to the idea of philosophical profundity). It forces any reader to share Hekabe’s ‘explicit doubts that the gods concern themselves with humans or exist in their traditional form at all’. In the end I think the adjective ‘bleak’ that Hall uses to describe Carson’s translation is one that is admiring of the poet’s ability to find the root of Euripides’ probable atheism in Hekabe’s statement: “The gods had no interest in us / except to ruin me and despise Troy”. Indeed there is the highest praise intended I believe in the statement about the choice of the medium of the ‘comic’, whose ‘conventions could have flattened distinctive literary qualities, but their book instead refocuses our attention on Euripides’ styles’. Yet Hall does not show how and why that is the case except in terms of the largely zoomorphic turn in the representation of characters (which doesn’t stop Menelaus being presented as ‘a phallic-looking piece of machinery, “some sort of gearbox, clutch or coupling mechanism, once sleek, not this year’s model”’). Yet her justification of these metamorphoses is doggedly (forgive the pun, Hekabe) that of showing her academic qualification to be equal to Carson’s (herself a Professor of Classics) and laying the reason for them at this ever -open door – ever open that is to distinguished academics. Too many these will seem as bad as other ‘abstruse references’ Hall otherwise condemns in the early part of her review:

Depicting Hekabe as a newly homeless canine matriarch was an obvious choice, given an ancient tradition that she was transformed into a dog and buried at Cynossema (“Sign of the Dog”) on the Hellespont. Half Carson–Bruno’s chorus of Trojan Women are also depicted as dogs, while the remainder are cows: this is reminiscent of the lauded public cattle herds of Troy that grazed outside its walls as well as the dogs that Homer tells roamed at Priam’s gates.[3]

For me, even if these hints are the case, they do not in themselves really justify the comic medium and its potential freedoms and space for novelty. Rather the reverse is the case. If the choice of the new medium needs to be justified (and that remains an open question for me) it must be because its own conventions enable the artists to achieve important aesthetic or communication effects in that medium. For instance I copy page 9 above from the publisher’s website. And one such freedom is the freedom given by loosening the narrative and adding elements that will emphasise new interpretive potential.

The text of the play in Greek, and in most other translations I have consulted has Poseidon at this point presenting and predicting the depth of Hekabe’s oncoming tragedy from things that (at this point in the play) she does not know – that her daughter Polyxena is already sacrificed to dead Achilles and the fate of the others, including herself, including allocation into slavery to hostile men and their families, is already decided. Bruno and Carson instead have him concentrate from the first on Hekabe’s passive resistance to the example of Helen. The latter is represented as a fox bitch with whom Hekabe, noble bitch that she is, has been forced to share a compound. Bruno differentiates them physically by the use of a cloth matting on which, Hekabe being still a ‘top bitch and the more regal is allowed to lie upon, whilst Helen occupies, at a distance, mere empty ground-space.

Mentally the zoomorphic queens are differentiated by the contents of their dreams which are placed as images (rather than words) in a thought-bubble for each. Hekabe dreams of her long years of pregnancy and motherhood, seeing herself elongated to give suck to multiple pups whose recent loss has all become too much for her. Her teats still drop the milk her now dead sons and removed daughters no longer ask to drink. Helen imagines an armoured animal (which may recall the Wooden Horse through which the Greeks infiltrated Troy and who now have become her lifeline) but it need not. It is a disturbing hard-to-interpret image even down to the attachment to its belly through which it is fed or drained. Other possibilities come to mind such as a placenta (although this does not seem a dream of pregnancy) but the point about the use of visual medium here is to raise meanings that do enter into determining without clear statement the kind of woman each character represents. Meanings remain open, although I think there is a sense in which whilst one dreams a past from which she is now isolated, the other dreams of some connection – of the mere hope of transfer to the jurisdiction of another man’s bed. But to Helen and her role in this version we will return later.

And the appendage to the artificial animal in Helen’s dream bubble hangs down the page, reaching towards the sea. Now the latter represents not only Poseidon’ ‘wall of water’ but the medium of her conveyance back to Greece. It is also a determination n Helen herself to remain fluid enough to survive, which we see later in the play, a fluidity not available to Hekabe. The conventions of the graphic novel opens up meanings, such as those, by using the organisation of the space of the page as a visual symbol of its most important themes. Against a totally black background on this page the spaces of the play are plotted. The rigid, defined and containing space of the women’s present incarceration is criss-crossed by obstructive lines (the lines represent the barbed wire of a prison as well as confine the characters to a deeper space behind them). They contrast ‘graphically’ (of course) with the white hatched space of less defined boundaries and relative fluidity representing the water on which everyone’s future (even that of watery Poseidon) floats. Of course such readings are fanciful but that is a freedom of a medium in which both picture, text and the organisation of space combine to tell a story and set the emotional tone.

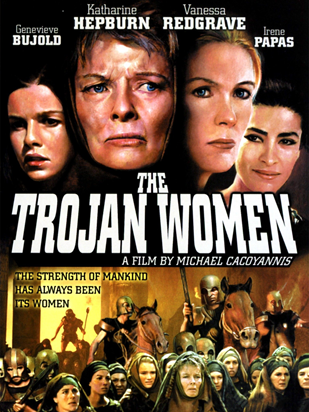

This then is how I would justify the use of a comic medium (if I had to) since in this medium space plays a large part in determining the pace of narrative and readerly engagement in its interpretation. In that sense it is no different from other media in which people have tried to retell this story. I refreshed my memory, for instance, of Michael Cacoyannis’ version on film in 1971 of which he was the writer, producer and director.

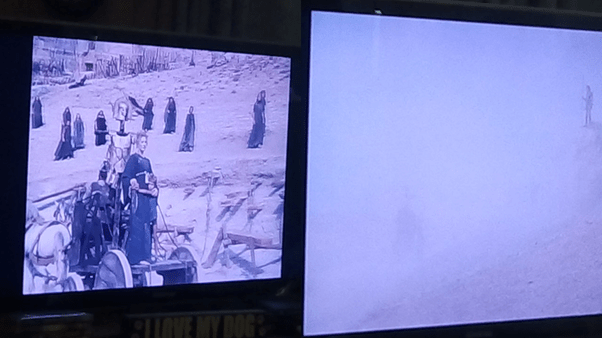

Hated as this film is (see the page from ‘Rotten Tomatoes’ from which I took the illustration above) I love it. It represents an attempt to reimagine the narrative possibilities of the older story using cinematic conventions to deepen and widen the narrative meaning. For instance, the women of defeated Troy are imagined on a plain in front of the walls of ruined Troy and their houselessness (better than the word ‘homeless because of the echo of King Lear) represented by their frantic and helpless forays across vast space in an attempt to fill it.

In contrast Helen (Irene Papas) is housed in a low built shack obviously once used to house animals serving as her cell. We see her through the obstructive lines of the wooden slats that confine her. It is even through those slats where we (together with the gaze of the other ‘freer’ women) see fragments of her naked flesh bathing in water that had been denied to the other women who wanted water to drink. The effects of exposure to hot sun, are more clearly given in the visuals of a film. The meaning attached to womanhood derives I believe from the visual tropes about the relation of women to the space. Locked out from the interior spaces, of city, home and house in their abject state, the only person living in interior space is in a prison, by Helen, who is alone the triumphant survivor in the film but only by virtue of extreme sexualisation.

Visual symbols tell a story that is not so clearly imaginable in the text alone. Carts carrying women to exile raise dusts that occlude them from vision even before perspective diminishes them – particularly in the case of Andromache (Vanessa Redgrave), as does the hovering ghost of patriarchal control speak through the silent armour of the dead Hector on the cart on which Andromache (and Astyanax on our first meeting) sit.

But film also allows Cacoyannis to reimagine functions like the use of a chorus in Greek tragedy. Choric odes are not delivered by the whole assembly speaking together but by a series of facial close-ups of individual women intercut by images of the whole group. This especially when they are seen speaking without the authority of Hekabe (Katherine Hepburn) in the foreground.

I find these effects both moving and powerful in representing a chorus but they are dependent on the conventions of film not Greek auditoria or productions – the ability to cut between close up and other shots to make points about the generality of experience expressed by a chorus and its reflections in diverse individuals, who nevertheless all gaze forward onto the viewer.

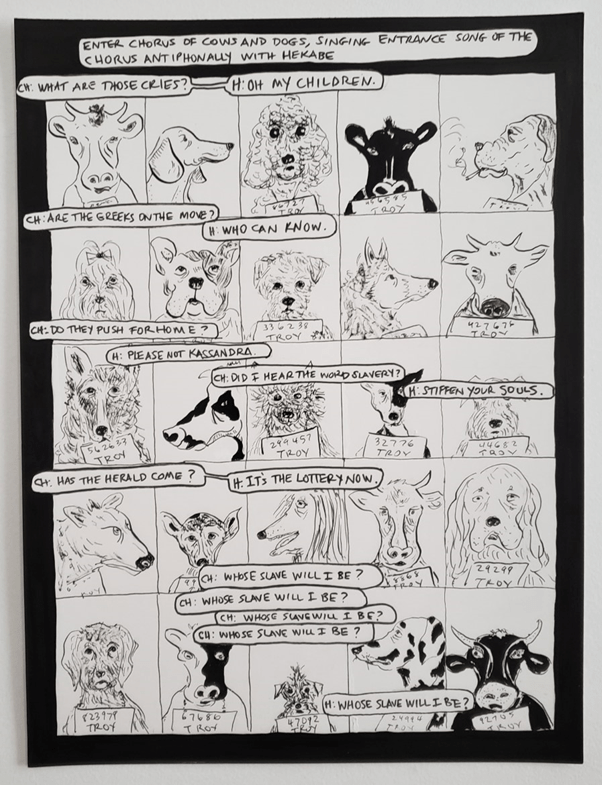

And I also make this point in order to better show the ways in which Bruno and Carson utilise conventions of the comic to reinvent the chorus in yet other ways, dependent on the conventions of their chosen medium. Thus the choric odes of Greek drama find a specific representation wherein the chorus is reimagined in this ‘comic’. In the first Choric Ode on pages 34 – 35, for instance, the chorus are a set of individuals all placed around the whole opening of the double page so that they form a border or frame for their song itself, represented pictorially by the Wooden Horse dripping with ink from its background black shading (or is it the blood of its victims which we allow to be represented as black in a black-and-white medium such as this) which the Chorus of Trojans have become. A similar convention is used on the double page 50 – 51 but here just as a preface rather than the body to the second Choric Ode. The latter appears on the next double spread. This prefatory linkage of the play’s events to choric themes both emphasise the vulnerability of Troy, especially its youth, to Greek power. It links the cruel taking of Astyanax from his mother, Andromache to Ganymede’s betrayal of his human role in the royal House of Troy. We will return to this transition for another purpose later. For now Let’s consider the way in which we see the chorus representing the citizens of Troy for the first time on page 16 (as reproduced below from the publisher’s website).

The title, given on page 16, for this entrance references the moment in the Greek drama itself and its choric conventions, such as the use of antiphony: ‘Enter Chorus of cows and dogs, singing entrance song of the Chorus antiphonally with Hekabe’. Antiphonal responses require two sources of voiced song responding to each other and this, as you might see occurs on page 16 alone as Hekabe responds in song to the Chorus’s sung chant, whom, as a Queen, she feels able to call ‘my children’. Hekabe (identified as H) is not represented other than in her chanted role in the part of the song, within the speech bubbles that record her part as it intersects in a variety of spatially organised ways with the Chorus as we move down the page. I think it is important that this imagines a communal chant from the Chorus as a whole (identified as Ch) because the page itself frames the chorus as a unit of separate and distinct animals each identified primarily by a prison number and the word ‘Troy’ that it is pictured wearing. This dialectic of the individuated absorbed in the whole is part of the experience the work needs to convey and this mode of expression is specific to the form of the ‘comic’. Hekabe too has been absorbed in this bigger picture formed by the citizenry and her responsibilities for their fears and cares.

But page16 cannot be read without its reflection on page 17 and I reproduce below the overall effect.

Being a graphic art, variations in tonality can be conveyed by the quality of focus and definition of drawn imagery as well as in spatial organisation of text; thus another form of expression available only to this medium gets utilised here: potential expressive forms rooted in the form and genre of the ‘comic’. The whole of page 16 is repeated on page 17 but with the variation in which the lines of the drawn figures appear less distinct and detailed. Moreover, the background shading makes the figures represented and background harder to see distinctly and in distinction. Of course the fact that the page is a repeat with the variation is grasped immediately but to what effect. To me it felt like we were seeing the negatives of a photograph or a ghost page imprinted by accident on some different kind of surface than the clean white of page 16. It is as if, for that reason, this page serves a function in addition or underlying those served by the primary printing of page 16 which reflects it, perhaps in a mirror or ‘glass darkly’. The text bubbles on this dark mirror page 17 all come from Chorus alone but are also less well organised spatially than on page 16 because they are no longer responses to the principal singer. This queered pitch – a kind of ghost of a page – allows the artists in graphic art to play games in which the choric responses emerge in ways that are deliberately estranged by anachronistic language (‘Mr. White Slaver’, ‘your phone’) and questions that in their ridiculous distance from the possible for Euripides betray the deepest fears of the marginalised and oppressed.

Of course I cannot guarantee these readings. They are precisely that but they are freed to our capacity to read them by the genre’s characteristics that were not available to Euripides as a dramatist – or even Cacoyannis as a film-maker. If we examine how transitions are handled here, we see the representation of character and symbolic meaning are conflated. At the bottom of page 17 is a black crow. It feels like a symbol of fear or augury of ill fate, as In Ali Smith’s 2016 version of Antigone, another favourite book of mine (as of Edith Hall, who also mentions it).

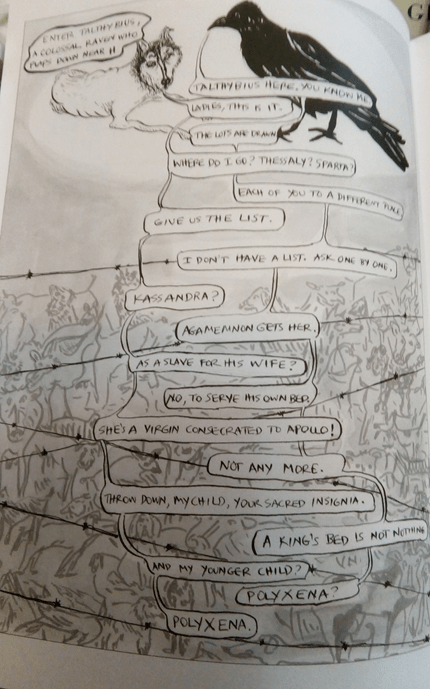

This parallels the sense of underlying fear but it is also the oncoming entrance of the Greek character, Talthybius (represented as a crow), who (as is appropriate for his rank as a soldier) addresses the chorus – now become faded representations between randomly criss-crossed barbed wire – only through the person of the Queen. I will cite this page to look at another innovation of this book based on the conventions of comics, which is the treatment of the sequence of speech. This is argued by Edith Hall to be one of the felicities of this version although the way this works technically is not considered. She says:

For Carson soon concentrates on the unique tonality of Euripidean tragedy. … Euripides’ theatrical verse was already acknowledged by Aristophanes … to sound like ordinary people engaged in spontaneous, idiomatic conversation. Euripidean diction, especially in rapid-fire dialogue, turns out to be suited to speech-balloons.

But how and why is Euripides’ ‘tonality’ as suited as it is to ‘speech balloons’ and is there something about the way the collaborators use speech balloons that contributes to that? I could take a scene from almost anywhere to analyse the way ‘speech balloons’ in this particular ‘comic’ work but let’s stay with page 18, since it follows on with where we were in the narrative.

The speech balloons use a convention we see in other comics to communicate the tonal variation of dialogue by allowing themselves to form a dual intersecting tree structure that is almost organic, except that it grows downwards, one stem for each speaker. Each speaker’s words are linked by a narrow channel. Think of it now as a trickle in a fast moving waterfall that pools every time there is a plateau in the rocks, that is when the character speaks. The position of the trickle is sometimes occluded and shifts directionally. We are tempted to find meaning in those visually comprehended spatial dispositions. Note for instance how Talthybius’s link line between speeches (or ‘narrow channel’) is occluded as he sneaks in a reference to the fact that her eldest daughter is no longer probably a virgin and has already been taken by Agamemnon. The effect is to reproduce pools of speech that shape themselves into an integral structure even though fractured by tonal shifts as speech plays different roles – to inform, to persuade and to assert the reality of distinctly gendered military power. This is a masterful use of the genre by the collaborators where the appearance of the verse is revived as a factor in poetry (as we sometimes forget – except in the obvious cases such as Herbert’s Easter Wings which shape the angel’s open wings – it always is).

I think we need to see the nature of these innovations as only made possible by the comic form in order to really value Bruno and Carson’s decision to translate the drama and its verse and song thus. But it also means that we can praise these collaborators not by searching for yet more ‘abstruse reference’ to our own field of expertise, as Hall sometimes does, but to the actual artistic achievement caused by utilising the affordances offered by the medium. I am using the term ‘affordance’ here in analogy with its use in James Gibson’s theory of direct perception to refers ‘to the opportunities for action provided by a particular object’. Of course in our context the object of interest is a genre; in fact, a comic.[4] For instance the convention of the variety of usages of the ‘speech bubble’ in comic’s is referred to above. Here I want to take issue with Edith Hall’s explanation of the use of a poplar tree to represent Andromache in this play. Her analysis ends quite brilliantly and really enlightens us as to how Bruno and Carson’s use of affordances in the convention work but stops short of that, in order to emphasise the more reference to obscure classical references (which, by the way I do not doubt Carson knew and may have ben referring to). I just don’t see how the reference to Cratinus By Hall (or even Carson if that is the case) helps us appreciate the art offered:

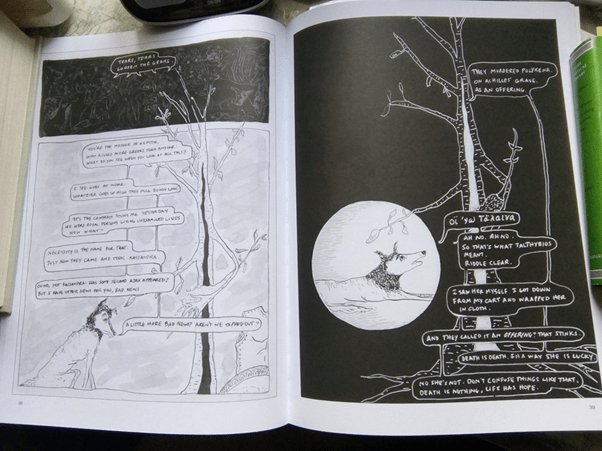

Why a poplar? The scenes of Astyanax in this tragedy, ultimately ending in his murder, are so shocking and physical that a comic-book drawing of a human mother and infant would risk turning tragedy into melodrama. In the myth of the Heliades, the daughters of Helios were turned into poplars, transfixed as they mourned their brother Phaethon in eternity. Astyanax is addressed at one point as a “mushroom”, and ancient horticulturalists well knew that mushrooms flourish in poplar stumps. But a fragment of the comic poet Cratinus (not so obscure that Carson, an accomplished Greek scholar, can have avoided it) tells us that “the poplar view” proverbially denoted a seat in the theatre so high that it had no view of the stage. Andromache’s suffering is so exceptional that it escapes the boundaries of art: the frames containing her cannot accommodate her full height and topmost branches.[5]

Let’s examine this insight. That Andromache is often presented as too big for the frame in which she sits is true of pages 39—41 inclusive and some later pages, although often this is to emphasise a change of focus of the page from her to her bud, the child Astyanax. It is also true in relation to the frame on page 38 but here the frame does not fill the whole page. We see the topmost branches of the poplar crossing the gutter between the frame holding the view of her and Hekabe as principal characters and the chorus. Nevertheless the insight stands, although I would still argue that this framework of interpretation is not assisted by the reference to Cratinus on the theatrical architecture at the Athens auditorium. After all, Andromache is the character seen rather than representing an audience’s possible point of view of her and other actors.

Likewise the references to the characteristics of poplars known to the Ancient Greeks seems singularly unhelpful critically and renders it an attempt to display arcane knowledge. After all, these are modern artists who need not contain their reference to the poetry of the Greeks. These kinds of echoes are anyway difficult to prove so I will not join the contest by putting in a plea for the possible influence of Gerard Manley Hopkin’s Binsey Poplars, about trees felled in 1897. However the tone of the poem might make us look more closely at how Andromache is portrayed as a poplar and it is as a polar – of course transplanted – but also wounded and fractured, which is why I recall Hopkins’ words about a feminised nature which is both poplar and what she represents – which is growth:

O if we but knew what we do

When we delve or hew —

Hack and rack the growing green!

Since country is so tender

To touch, her being só slender,

That, like this sleek and seeing ball

But a prick will make no eye at all,

Where we, even where we mean

To mend her we end her,

When we hew or delve:

And this is, whether from Hopkins or not, what I sense about the determination to show Andromache as a poplar that has suffered some ‘hack and rack’.

There is a deep fracture in her trunk, whether shown in negative (as white on black) or the reverse. At the point of her deepest anguish she fragments, or seems, to the vision so to do: ‘A Blizzard of Broken Branches, Twigs and Leaves’.[6] Hekabe on page 39 has a kind of spotlight on her and returns to Euripides’ Greek to speak, ‘οϊ ‘γὼ τάλαινα’ (translated by Kovacs in the Loeb edition of the Greek text as ‘O woe is me’).[7] The height of what Hekabe learns from Andromache, that tall aspiring tree breaking frames and gutter boundaries, is that ‘whatever goes up high they (the Gods) pull down low’ . For readers of a comic high and low are visually demonstrated by the positioning of Andromache’s hubris and Hekabe’s resignation. The deep irony of these pages is that though Andromache presents Hekabe’s plight as tragic but specific to Hekabe, it is the very fate she will suffer. Notice that the Greek lament covers the Astyanax bud, the child that will, like Polyxena, be also lost.

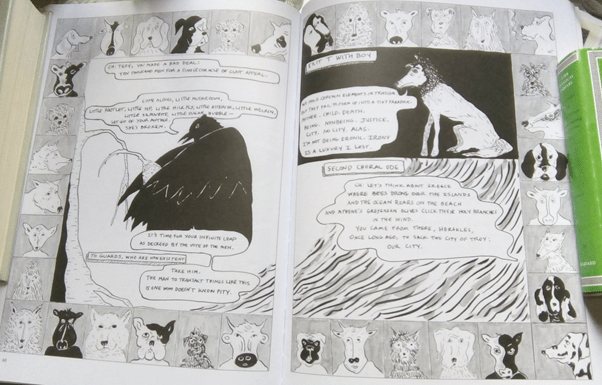

And hence we can return here to Hall’s query about whether a comic can do justice to the ‘metaphysical profundity’ of the play. My answer is that in the hands of consummate artists, it can indeed – although I think this is also Hall’s answer (if in a muted version of it). To support this I would look at how this ‘comic’ uses its generic conventions to show transitions and continuity not only in narrative but in tone and focus. On page 48 and 49 the whole spread covers a transition from the taking of Astyanax from his mother by the crow Talthybius to The second Choral Ode. In the latter the neglect of suffering humanity by the Gods and those humans who rule humanity in the mass is the burden, particularly in the story of Ganymede who as ‘butt-boy of the gods’ whose preferences are described this:

You sit by the throne of Zeus

And sip or smile,

While your home land (sic.) is deleted and removed.[8]

Carson rewrites a speech of Hekabe’s to make it the centre of the intended metaphysical depth of the choral ode in which the robbing of young growth in the form of the ‘little rootlet’ Astyanax is tied to the refusal of the high and mighty to nurture the human common many rather than the leisure and pleasure of the rich few.

The overarching theme is stressed by having the Chorus represented yet again as the framing border of this double page. The actual transition on the page is from the robbery of the specific youth who is the literal future of the Kingdom (Hector’s son) to some more fluid and imaginative version of organic growth and youth, with the return of the hatching that represents the fluid sea between Greece and Troy. It does it by yoking together the human actions in the tale and the mythic symbols from Trojan myth and history and the consequences of the latter in the moral universe.

In my view, but I am no way expert, the speech of Hekabe here differs in focus quite a lot from the stressed content of Euripides and the aim is to cut even deeper into the metaphysical potential of the play’s take on the theology, philosophy and politics of the attitudes which make human life meaningful and sustainable.

For Euripides’ Hekabe really bemoans the injustice of the Gods because they rob humans of agency in the moral world by making effective human power impervious to human suffering and common experience. She becomes a grieving Mother again, but now of what Astyanax represents not only as a grandson but as a principle of ongoing life.

ὦ τέκνον, ὦ παἵ παιδὸϛ μογεροῧ,

σνλώμεθα σὴν ψνχὴν ἀδίκως

μήτηρ κἀγώ. τί πάθω; τί σ’ ἐγώ,

δύσμορε, δράσω; …[9]

Translations often make many more words in English out of the economies of Greek, such as in the use of ἀδίκως. Kovacs plainly translates in the one word ‘unjustly’ in English in the Loeb edition. James Morwood expands to: ‘There is no justice here’. Diane Arnson Svarlien in the Hackett to a more idiomatic but definitively straight, ‘There’s no justice’.[10] In her introduction to the newest Oxford Classics translation by Morwood, Edith Hall argues that the characters throughout, but Hekabe in particular, ‘strain their intellectual and theological muscles as they attempt to find a reason for the catastrophe, an impulse in which the pressure of bereavement quickly transforms into a quest for a single scapegoat …’.[11] This captures the swing in the play between being a metaphysical and, almost in a breath, a psychological drama: in which ‘blaming’ trumps inquiry into truths. The wonder of this moment in Carson and Bruno’s version is that the use the continuity assumptions between the frames on these double pages (for instance the flow of a tidal sea covers two of the subordinate frames within the choric border gives great prominence to Hekabe’s speech – lit as she is ion a dark background – that accompanies the departure from the stage of Talthybius. I will transcribe Carson’s version here:

We hold certain elements in tension

But they fail to form up into a tiny paradox.

Mother. Child. Death.

Being. Nonbeing. Justice.

City. No city. Alas.

I’m not being ironic. Irony

Is a luxury I lost.

To my taste this is a most perfect moment in which Hekabe, as she is conceived in this work, stands between a world of linear onward events and the flow back and forth of recurrent questions about how life should be lived. Drama is a kind of ‘tension’ in which categories play with their nominal opposites in the search for meaning – what it means to be mother or child is almost the same question as being ‘of the city’ or ‘rejected by the city’ or the vexed question if the ontology of things (‘Being. Nonbeing’). If we seek ‘metaphysical profundity’ look no further. Carson decides here to show, but for a moment, how a great soliloquy (like Hamlet’s ‘To be or not to be’) comes about from psychological pressure so great that it forces us to question whether being human has a meaning at all, or if so, what is it’s source – in the arrangements of human generation, our social arrangements (such as the Athenian polis) or just something superficial, a ‘luxury’ greater than that afforded to other humans such as the Chorus will show us Ganymede seeking instead of a moral and social purpose in the Choric ode to follow.

In my book the comic here is vindicated by our collaborators as a mode of such questions, even in the very tension between its visual, linguistic and emotional flows and stasis. That it is too easy to just blame Helen for everything has already been shown in this version where Hekabe realises that she maty as well just sleep as blame Helen as a way out of the larger issues this play. Those issues concern the fall of human civilisations and values – even the bond of parent and child – again as in King Lear. You might guess that I rate this work very highly INDEED.

All the best

Steve

[1] Hekabe prior to the Second Choral Ode, Bruno & Carson (2021: 49)

[2] Edith Hall (2021) ‘Sweet violence: Euripides as seen by a poet and a comic-book illustrator’ REVIEW of THE TROJAN WOMEN: A comic .by Anne Carson and Rosanna Bruno in The Times Literary Supplement [TLS] [online] (May 21, 2021). Available at: https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/the-trojan-women-anne-carson-rosanna-bruno-review-edith-hall/

[3] Hall (2021) op.cit.

[4] No reference here needs more than the Wikipedia page on this theory’s originator for it to be understand and this page is cited here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_J._Gibson

[5] Hall (2021) ibid.

[6] Bruno And Carson (2021: 45)

[7] Euripides (Edited and Translated by David Kovacs) Trojan women line 624,LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY (Euripides IV) 1999: 76f. Cambridge, Mass, & London, Harvard University Press. 1 -144

[8] Bruno and Carson (2021: 50f.)

[9] Trojan Women, op. cit: ll. 790-793 Forgive transcription errors. I pick each letter (and lose patience with my poor use of the ‘Extended Greek’ option sometimes

[10] Oxford World Classics 2000, p. 61, Hackett 2012, p. 151

[11] Edith Hall (2000) ‘Introduction’ in Euripides The Trojan Women and Other Plays: a new translation by James Morwood Oxford, Oxford University Press.

2 thoughts on “‘WE HOLD CERTAIN ELEMENTS IN TENSION’. Making a ‘comic’ out of a ‘tragedy’: drawing from inexplicable pain and blaming? Struggling to critique but thoroughly loving Rosanna Bruno with text by Anne Carson (2021) Euripides, ‘The Trojan Women: A Comic’. REVISED 21st June 2021.”