‘SO WILL FALL // whose fault? / Paradise Lost Book 3’.[1] Whence queer poetry? Reflecting on Andrew McMillan (2021) pandemonium London, Jonathan Cape, Penguin Random House. Forgive misunderstandings and any gaucheness @AndrewPoetry

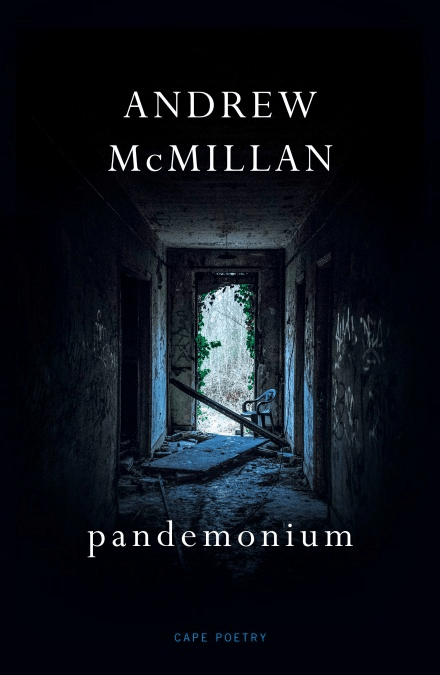

Front cover

For other Andrew McMillan based blogs of mine see list at end.

I think when queer poetry takes on Milton it has matured in a rather wonderful way. Now it is not a matter of influence I think, though the sound qualities of McMillan’s poetry here takes a kind of weight that might owe something to that poet. It is more to do with a queer poet themselves taking on very self-consciously and therefore with risk Milton’s dedication of a major poetry to the investigation of how and in what way there is a responsibility for the shit that happens to us in life. Though necessarily experienced in a different kind of age and time, and with less reliance on myth, a mature queer poetry takes on responsibility that must be not only placed (even if variously) so that it can be understood, but also faced – and its consequences felt and worked through. Nevertheless, there is hardly even a clear quotation from Milton, though the title of this work is taken from a word invented by Milton to name ‘the high capital / Of Satan and his peers’ built by the fallen angel Mulciber, the architect ‘known / In heaven by many a towered structure high’.[2]

John Martin: Pandemonium (1841) Height: 123 cm (48.4 in); Width: 185 cm (72.8 in), Louvre Museum. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Martin_Le_Pandemonium_Louvre.JPG

Yet, after a painful poem in which the word ‘pandemonium’ is associated to the madness both of Bedlam and demonic possession, the first section of the collection is prefaced by a sub-title which with the epigram form two separated parts of one quotation from Book 3 of Paradise Lost in which God predicts that man will be tempted and will to temptation Fall:

… : so will fall

He and his faithless progeny : whose fault?

Whose but his own ?

Paradise Lost, Book 3 lls. 95ff.

God says these words to his son, without yet revealing the consequences of their narrative to the son’s future role on the cross, that though Man is bound to ‘fall’, that fall is Man’s ‘fault’ (including in that fault both the present human beings in Paradise, Adam and Eve, and ‘their progeny – even those yet unborn) and Man’s ‘fault’ alone. And therein lies a history in which the responsibility for a creative work that fails to meet up its intended ideal is to be discussed throughout the history of later literary history – or as Peter Mayo puts it:

William Blake claims that Milton, in his epic poem Paradise Lost, was “of the Devil’s party without knowing it.” The eighteenth century visionary poet states that Milton wrote at liberty “of Devils & Hell” because he was “a true poet” who regarded that kind of Energy “call’d Evil” as the “only life”. He considers Energy to be opposed to Reason, the force which, in the poet’s view, restrains desire. … Blake appears to suggest the view that the true poet should exalt passionate life and this is what must have led him to believe that Milton was unconsciously on Satan’s side.[3]

If a great poem like Paradise Lost can invert the binaries on which its meaning appears to rationally depend in its readers and continue to do so, that is because poetry itself is taking responsibility for the failure of a whole world of determined reason and ordered certainty. Instead poetry might openly espouse ambiguity, tragic failure, madness and disorder.

Responsibility has never been a comfortable theme for queer writers, in part because the issue of ‘laying blame’ and ‘finding fault’ has been played out so often in our lives to find novel ways of marginalising queer self and social expression. Those ways include censorship of homosexual published or privately distributed materials from book burnings upwards in degrees of ‘tolerance’, the prohibition of public meeting or expression (even after the 1967 Act), eugenics, parental guidance and penalty (directed at and sometimes then redirected from parents) and the usual call that the behaviours called gay were either moral self-indulgence – the fault being then in the terms of Milton’s God, ‘whose but their own’ – or a pathology acknowledged to be difficult as it is necessary to cure by whatever means.

However, I would also argue, mainly on the basis of observation over my life-span and constant reflection, that there were other reasons for the flight from discussions of responsibility too in queer communities. One was evidence of decisions made by individuals and groups of queer people. on the basis of self-preservation and usually taken unconsciously, that surviving the oppression of homophobia and marginalisation of heteronormativity was something for which each individual had to take their own responsibility. This was by no means universal and the early movement was characterised by self-help group-work and radical group therapeutic approaches and practices, such as those so beautifully described by Kate Millett in her autobiographical accounts of mixed sex communal life. Parisa Zamanian has analysed the processes by which communal pressures are used, for instance, in Tumblr queer communities to make individuals totally responsible for themselves, although sometimes in the name of ‘self-care’. This is perhaps inevitable in an area of moral hygiene controlled largely by contemporary but culturally specific White Western mores.

queer Tumblr users use the process of calling out to compel each other to take responsibility for actions and missteps. …. Tumblr’s processes of calling out can evolve into online wars of words that generate a mob-like mentality, privileging the voices of some, silencing others, and as Bell argues, forcing the rest into anxiety and silent fear.[4]

If I read this correctly, this is the context in which McMillan begins to understand the processes by which ‘shit that happens’ in queer lives, in greater frequency than other populations owing to a number of factors but certainly including ubiquitous social oppression, such as mental health breakdown, suicide and the breakdown of otherwise sustaining relationships. And this is the arena of fault into which pandemonium casts itself or into which it falls: ‘So the Fall’.

Kate Kellaway, in her sympathetic view of this collection of poems appears to argue that the collection itself shows paradoxical qualities, since though ‘there is no poem in it unmarked by suffering’ and covers ‘a period of turbulence involving the depression of his partner, the death of his sister’s baby and various reckonings with himself’, it is, she says, ‘the overall quality is of stunned calm’.[5] She also mentions how that ‘calm’ facilitates, again almost paradoxically, the mastering of:

the art of self-reproach. He reproves himself early on, in an untitled piece, for failing to spot his partner’s slide into depression, realising “too late what is about to happen”, recording how, after he said “something unconsidered”, his partner curled up “like a draught excluder”.

This quality of ‘emotion recollected in tranquillity’ is not so new an aspiration in poetry of course[6]. It is another sign of the maturity, within traditions of poetry writing that are not necessarily queer, that demonstrates that we need to be responsible for each other (at least enough to understand why we all ‘fall’ sometimes) and not project further ‘fault’ onto the fallen, in the manner of Milton’s God in Book 3 of Paradise Lost. However, I disagree with Kellaway about the choice of title for this poem, for the collection of all the demons it implied was, in all probability, as much about the role of poetry – a kind of possession by ‘daemons’ – in the original sense of the word in Greek. This seemingly supernatural inspiration is one which all poets need to struggle to contain and order rather than just referring to a palace full of varied diabolic entities serving their master in Hell, as Nicholas McDowell’s new biography of the first half of Milton’s life has recently told us.

The thing that holds this collection together is the moral territory on which it has been forced to reorder the emotions of life, and in this case specific queer lives that intersect with other lives through other bonds, like those of biological as well as chosen family and communities, even those of ‘neighbours’ to whom we contingently relate. The boundaries of responsibility that we hold for each other are examined in and through these diverse networks. And it is in these networks that the attribution of guilt and the growth of suspicions of each other occur in all communities, as described in the ‘Knotweed’ poems:

the neighbour thinks someone is stealing

his chickens …

…

… I sigh say rumour spreads

too quickly through this street another

neighbour asks if we’ve been growing weed

or if the other neighbours have

where is that smell coming from? they shout

…[7]

That a gay couple living in a suburban street well out of Manchester might often attract suspicious rumour is a knowledge that lies behind this poem, but what matters is that this tacit perception of oppression, even in small things, is not unlike the insecurity the poet feels about his own domestic life with his partner and the fact that both of them feel their emotions, at some level below the surface, disturbed. Those levels below the surface are beautifully symbolised by ‘knotweed’, another pernicious ‘weed’ like the likely possession of the ‘weed’ marijuana his neighbours expect in a gay couple (or is it someone else to deflect the pointedness of the accusation) otherwise living outside norms safe to their thinking. I have tried to express how ‘knotweed’ works as an image in this poem in an earlier blog on an earlier public airing of these poems in Granta magazine and will therefore not repeat that material, other than in giving the foregoing link to that earlier blog. What needs repeating is that the insecurities that people feel about our homes, neighbourhoods, and relationships both close and more distant are intimately related to the sense that someone must be to blame for the underlying feelings of danger to everything we hold dear that sometimes attacks us in the presence of obvious mutability and possible or actual death.

That is why Kellaway is so sensitively right to see the quality of these poems in the moral acceptance of that we all participate in responsibility for things going wrong, in as much as anyone is responsible for those things. Because mutability is everywhere – even in queer lives and forgiveness may be all we can expect for our inability to always know how to handle it other than through conscious or unconscious cruelty of leaving what hurts us behind or throwing it away:

… and the fungi unkempt

sprung up from the mossy ground and flung

like scabs across the lawn sometimes I need

the sound of something pulled up from the roots

and tossed aside …..[8]

The angry attempt to deal with pain by destroying the nearest thing we can attribute as its cause has never been better described in poetry than this. At other times we might realise that some problems are built into the very stuff of what life is – its very architecture – as in this most haunting moment experienced by the poet after leaving his partner (let’s honour him with his name, Ben) ‘hooked/ up to the drip’ tackling his overdose in hospital. He hears:

the skyscraper singing its one long metal note

back into the weather we’re told

it’s something in the way it’s built

a fault of the architecture ….[9]

The use of the word ‘fault’ here is both precise and resonant with themes I’m trying to elaborate in what it is a very complex poem with no easy access to its meaning, except through empathic emotion of a very subtle kind. For is a ‘fault’ in ‘the architecture’ necessarily anyone’s fault – cracks, like shit, happens in life, relationships and buildings. Examining responsibility then is a royal road to something new and something even more beautiful than celebration in queer life, where we need not ‘pride weekend’ and our knowledge that, at this time, ‘city streets / only speak the language of the body’ but to cultivate our garden and repair the blight of ‘this changeful month’. I find myself so moved by these poems.

But as a queer man I am most moved when the poems unite the physical honesty of visceral realism of McMillan’s earlier collections (physical and playtime) but mix the persistence of bodily need in those collections, in poems written of the most inappropriate of emotionally charged circumstance and with the prompting of even pornographic stimulus, hurt vulnerability and moral awareness. In such honest writing the meaning of virtues like ‘love’ and ‘patience’ still matter and are deeply meaningful and hence these words unashamedly appear. To show how this works in a poem so startling and yet so beautifully right like that which starts ‘ill again wanking at ten past three’ is both too difficult and feels to ask for too much readerly exposure, just as the writer has exposed himself so bravely.[10]

And I think the upshot of this new kind of poetry is the ability in this remarkable still young poet – to reinvent very old forms like the sonnet sequence (in ‘Knotweed’) and the unashamed love lyric that bears within its aching authentic emotion the admission that the age we inhabit lacks the qualities of the ones in which such poetry was originally written. But that’s a very good thing perhaps:

the night is perfectly tuned slow forcing

of the plum trees and their fruit buzz of motorbikes

on the road undressing to land beside you

all night the winds come over us

like intermittent water Ben I am not

sure what I mean by this but I’ll spend my lifetime

coming home to you [11]

There is so much stark painful beauty in this book. Andrew McMillan is already establishing himself I think as the best poet queer people ever had – at least not one that was out in the open so nakedly beautiful with emotion.

All the best

Steve

For other Andrew McMillan based blogs of mine see:

- On the Granta publication of Knotweed draft:

- On his play Dorian

- On a commissioned work for the Hepworth Gallery at Wakefield

- Record of some tweets on a new narrative poem (otherwise unpublished I think)

- On being taught by Andrew McMillan

https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2019/11/16/a-new-poem-podcast-by-andrew-macmillan-andrewpoetry

[1] Section Title and epigram from that section of Andrew McMillan’s pandemonium (2021: 3f.)

[2] John Milton Paradise Lost Book 1, 756f. & 732f. respectively.

[3] Peter Mayo ‘Of The Devil’s Party’ The University of Malta. Available at https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/bitstream/123456789/23709/1/Milton-of%20the%20Devil%27s%20Party.pdf

[4] Parisa Zamanian (2014: 44) ‘Queer Lives: The Construction of Queer Self and Community on Tumblr’ May 2014

Thesis for: Master of Arts, Women’s History, Advisor: Julie Abraham. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311370905_Queer_Lives_The_Construction_of_Queer_Self_and_Community_on_Tumblr

[5] Kate Kellaway (2021) ‘Andrew McMillan: pandemonium review – steeped in suffering’ in The Observer (online) Sun 6 Jun 2021 10.30 BST. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/jun/06/andrew-mcmillan-pandemonium-review-steeped-in-suffering

[6] The phrase is from William Wordsworth’s (1800) ‘Preface’ to the Lyrical Ballads Available at: https://www.bartleby.com/39/36.html

[7] McMillan (2021: 61)

[8] ibid: 68

[9] ibid: 9

[10] ibid: 19

[11] ibid: 72

5 thoughts on “‘SO WILL FALL // whose fault? / Paradise Lost Book 3’.[1] Whence queer poetry? Reflecting on Andrew McMillan (2021) ‘pandemonium’. Forgive misunderstandings and any gaucheness @AndrewPoetry”