‘… far from being spontaneous studies modelled from life, these bodies were made up from a limited number of pieces [translation of abattis, which is more strictly translated as giblets] put together in a diverse range of ways’.[1] We are so used to the lies that idealise the human body in art, life and the links we make between art and life that we forget just why Rodin’s practice as a sculptor matters so much. On visiting the 2021 exhibition at the Tate Modern and reading the brilliant catalogue by Nabila Abdel Nabi, Chloé Ariot, & Achim Borchadt-Hume (editors) The Making of Rodin: The EY Exhibition, London, Tate Enterprises Ltd.

Jonathan Jones in The Guardian recently said that: “All the plaster casts in the world cannot convince me Rodin was a modernist. Luckily his fantastic, eloquent art is amazing”.[2] The intention is to throw buckets of cold water on the views of the curators of Tate Modern’s stunning new exhibition that makes us see Rodin as if for the first time again. Jones’ last word, literally, on the matter is that Rodin is ‘simple’. What I take him to mean is that, far from being a ‘modernist’, which is not a word I noticed that the catalogue elaborates upon or even states. Jones says Rodin is really at his best making in demonstrating the ‘expressiveness of his vision’, which could be taken to refer to the classic reading of the artist by Louis Weinberg in 1918.

Great artists of all times have frequently strained at the leash of form, in their eagerness to obtain a fuller expressiveness.[3]

And what is that that vision? Well, according to Jones it seems, you approach it by avoiding all ‘theory’ except for tools in the most tired forms of the discipline known as the history of art (although I have a soft spot for Weinberg) using historical or ‘biographical context or iconographic meaning’. Yet theory in the hands of these innovative curators – and some very traditional feminist art historians like Anne M. Wagner – is really no more than having found a language more responsive to what is, and I believe would strike anyone, as distinctively challenging in Rodin’s response to the human body and its variability. This is a variability outside contexts other than those of mythical or idealised narrative expressions that are the sources of much traditional iconography and takes on the forms that are labelled physical and mental disability or illness.

We do not need to evoke ‘theory’ to see that the ‘lack of defined form’, which ‘is exactly what horrified Parisians when Rodin’s full-sized plaster model for a monument [to Balzac] was unveiled in 1898’ is as much an intelligent response to the formal innovations of that novelist as to ‘theory’, whatever that is. This is probably what prompted Émile Zola to see the similarity between Balzac and Rodin.[4] Intelligent seeing is not dependent on ‘theory’ and this exhibition is about very intelligent seeing of the issues thrown up by some of Rodin’s brilliant formal experiments. This is how I intend to describe my own perceptions.

But first of, just an explanation of my phrase above, ‘Rodin’s response to the human body and its variability’. we like to think of our culture as of one that celebrates the body (electric or otherwise) but in fact the body in many cultures but especially in the history of the Occidental tradition, since at least the then near global hegemony of Classical Greece in the fifth century BCE, is actually treated as the site of radical ambivalence, which is sometimes interpreted through symbolic binaries that tend to interpret each other – beautiful against ugly, formed against deformed, healthy or unhealthy, familiar against alien – as The ancient Greeks in fact treated of Persian bodies. In fact those binaries cover over vast variations between bodies that are wonderfully explored in Chris Townsend’s 1998 wonderful book for an old Channel 4 series, Vile Bodies: Photography and The Crisis of Looking.

This book, and the series, showed how the bodies of people with some variation from a norm (if indeed it is that and not merely a cultural or social cognition) are made ‘other’ in some way. In no way is this more ignored than in the arena of physical or visible body difference that are superficial or structural. This is explored in a wonderful novel by Alex Allison (use link to see this if interested) that I have previously blogged upon. Lumped into this ‘otherness are bodies that are accidentally or genetically different, older bodies. bodies presenting themselves as a problem as in conditions such as anorexia or food addiction or just very fat or thin bodies, dead bodies and (the othered nature of which in our culture we often forget) children and young people and their choices of, or culturally prescribed, body art.

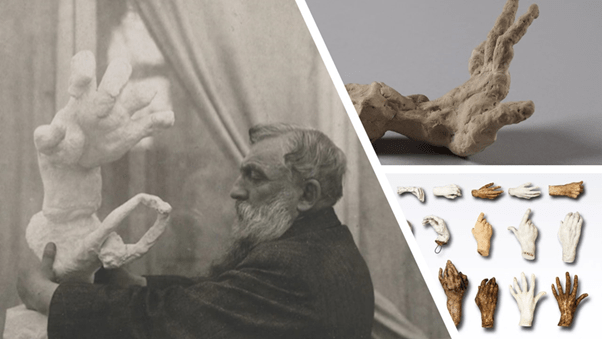

In this arena we should place Rodin’s interest in photography of real hands, including Charcot’s psychiatric patients, elders and the re-formed or reconstituted body where variations in shape, gesture (or both in interaction), size and perceived age are utilised for artistic effect – even if for limited viewing as were some of Rodin’s plaster casts at the clinically lit Meudon Studio and private art gallery and now in the in the very early twentieth century the Musée Rodin.[5] These are the very plaster casts which Jones want to render meaningless in Rodin’s art, just as differently abled bodies sometimes see their bodies as rendered meaningless and marginal by others who pass as ‘normal’ by preference.

The production of varied forms of body parts – and especially hands – is likened in one essay in the Rodin exhibition catalogue (by Natasha Ruiz-Gómez) as the collection of ‘sculptural and corporal remains’, adding to the connection to the otherness of some bodies and dead bodies, as Mary Shelley explored in Frankenstein, that Rodin kept as plaster casts he named as abbatis or ‘giblets’, as he over-produced them for the Gates of Hell sculptural frieze, and which he collected from medical evidence of psychiatric ‘deformation’ from Charcot’s Salpêtrière patients.[6] Re-assembling the giblets also led to some very discrete and queer forms of art that this exhibition glories in, including some of the preliminary casts for the Balzac statue.

And whether Jonathan Jones likes it or not, Rodin himself in an interview shows that his preference for ‘that which is considered ugly in nature’ over ‘that which is termed beautiful’. In doing so he makes a deliberate attack on socio-cultural as well as artistic models of what art and beauty might be conceived to be all about: ‘in all deformity, in all decay, the inner truth shines forth more clearly than in features that are regular and healthy’.[7] This is not just about expressiveness it is about reforming ideological bourgeois and Western notions of ‘truth’ more effectively than any René Magritte or ‘modernism’ generally.

For it is only the history of art that thinks that art can have a history, or even herstory, separate from the history of every medium of communication or reflection ever invented or dreamed of in its course. Rodin saw art as continual reflections or even copying of variability in life; and only bad when art tries to imitate art. ‘(T)he copying of works of art is forbidden by the very principle of art’ as he says in his dismissal of restoration (or copying) projects performed on French Romanesque and gothic cathedrals.[8] And the point is variability and diversity (‘flexible elasticity’ is a favourite phrase of mine from The Cathedral is Dying) that has no place for a principle of beauty based on the selective principles that govern elites that believe that we must pare down or omit or in some way refine the stuff that makes up the real world of highly diverse forms.[9] And Rodin’s world, like the facia of a French cathedral, does not EXCLUDE the ‘ailing flowers’, the ‘faint’, the prostitute, the distressed, ‘mad’ or those in ‘old age’. It can see the beauty in damage, decay and death: ‘this morsel of carrion, this red as of a disease that burns, this mucus that oozes’.[10] If you like, Rodin is great because he invites diversity as the principle of art rather than of selection. In that, he, Balzac, Balzac’s Human Comedy novels and Rodin’s numerous casts and bronzes of Balzac – nude fat old men or over-exposing dressing gowns for such men – are of the same stuff.

The language of critique so disliked by Jones appears frequently even in the Tate’s give-away guide to the exhibition: fragmentation, repetition, assemblage, multiplication and appropriation. These are indeed important words in contemporary theories of modern art and perhaps more in contemporary theories of art curation. For an example see this article (use link) on the 1960s and after artist, Elaine Sturtevant, where the words scream off the page. But it would be a mistake to see the similarity, as Jones does, as a kind of modishness. They are appropriate words because they describe the activities through which art is made by Rodin. The contention of the exhibition is that Rodin’s work is not only an attempt to express its subject-matter but also to make integral to this the act of making sculptural art or painting.

We can see this as in this fine example from an essay by Anne M. Wagner which discusses the 1900 Mask of Rose Beuret (plaster) – Rose was Rodin’s mistress – as photographed By Eugène Druet in which the seams of the plaster casting are visible and have not been removed before the object is photographed:

… something else occurs. It is not simply that accident enters the sculpture, and with it, the contingent passage of time. The photo also manages to suggest not simply that we are looking at a manufactured object, but that the woman it represents is likewise the artist’s creation, her very being shaped by his mould. It is an effect revisited some two decades later in an extraordinary assemblage that conjoins a plaster mask of Camille Claudel and the left hand of Pierre de Wissant, From the Burghers of Calais. Apparently simple it is anything but. …The piece not only stages a meeting of male and female, but also sites that story in sculptural process itself. The result is what might be usefully termed a poetics of production – a poetics, because for Rodin, feeling and making are one and the same[11].

A ‘poetics of reproduction’ sounds modern and modish to Jones but can’t the same words be used to describe the themes of Tennyson’s In Memoriam, which has, as one of its central themes how and why art is made, even up to the point of the poem being read:

What hope is here for modern rhyme

To him, who turns a musing eye

On songs, and deeds, and lives, that lie

Foreshorten’d in the tract of time?These mortal lullabies of pain

May bind a book, may line a box,

May serve to curl a maiden’s locks;

Or when a thousand moons shall waneA man upon a stall may find,

And, passing, turn the page that tells

A grief, then changed to something else,

Sung by a long-forgotten mind.[12]

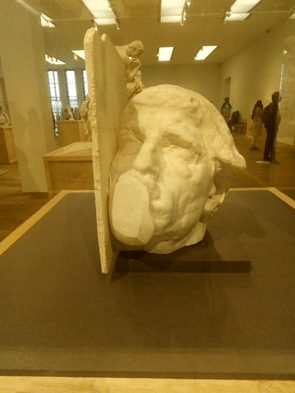

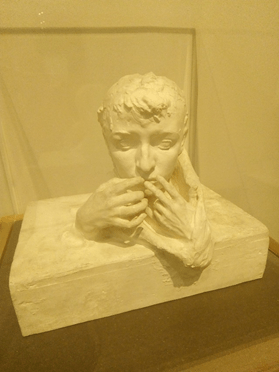

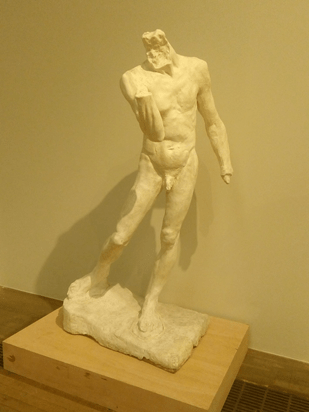

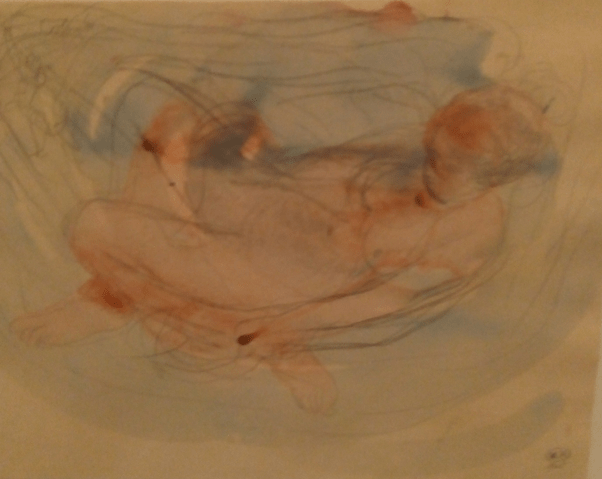

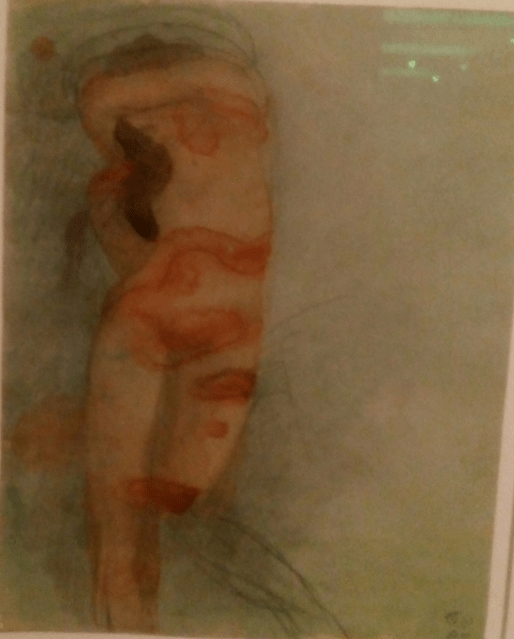

The time of making the poem either by poet or cognitively by a reader become likewise a theme here, as in Rodin according to Wagner. The plaster works in this exhibition are, of course, a stage in the poetics of production of sculpture but why does Rodin insist on this and in repeating it over and over in new forms of assemblage or deliberated deformation of the work. To test this look at these photographs I took myself from the exhibition from which I have on purpose left off titles, names of subjects or accompanying commentary.

The first thing one notices is the preference not only for the diversity of bodies taken as subjects but of the almost random distribution of parts or the deliberation involved in using non-finito works that also stress the appearance of unfinished assemblage or a difficulty in distinguishing between lack of finish or post-finished damage, especially in the headless and handless statue with an unfinished and yet to be fully shaped phallus. It is not just that this is about the assemblage of often random parts but that is also about the joining or articulation of them. Let’s take that pun where the unfinished bust has its mouth still sealed, or the diverse hands which still seem to be making or manipulating the mouths of a face that is probably not their own. It is not just that two busts are being approached by hands but that those hands linger over the parting of the lips. This is definitely a ‘poetics of production’ but it is also an appropriation of the things copied in order to be the work itself, an obvious appropriation because of the randomness of some of the parts in the assemblage, such as difference in either size and scale between the hands or between the hands and the bust. This may make us remember the differences of scale in Rodin’s repeated acts of recreation of his pieces. The Thinker is a very small iconic figure in the Gates of Hell. Separated into huge and massy isolation The Thinker must think of why he is so isolated from context. Indeed Rodin mentions him in connection with being akin to the ‘immense shadow’ that can be seen in the crypt of a great Gothic cathedral: ‘shadow that would have fortified this work’.[13]

And this is even more so in the drawings and watercolour washes discussed by Sophie Biass-Fabiani in the catalogue. Her words are quite brilliant. She draws our attention to the lack of match between the edges of wash colourings and drawn lines – the latter often clearly imposed on top of the washes so that sometimes the latter appears a medium that the drawn body is immersed within. The stand of a drawn figure can be turned into the posture of a swimmer by such immersion in liquid washes of pastel colours. Reds can appear as damage to the painting or wounds on the body of the figure. There is such indeterminacy here except for the signs of a master making his marks and somewhat surprising the figure subjected to these marks that they should appear thus. The two photographs I took are not discussed by this writer but you are helped by what she says to read them for yourself. I urge you have a go.

This figure is either floating in a pool of bloodied water or in the process of adult parturition. The one below appears to be the subject of violence that makes her by possessing her and damaging her in the process. It is to me a fearsome piece – full of dangerous images of male violence to women.

Of course opinions will differ but the disfigured figures in these drawings are the product not only of being created but being subjected to plastic violence that aggressively both shapes, forms and then deforms them. Truth is found in vile bodies – even in the victims of murder – in a way that reminds me, for some strange reason, of Sickert’s murder paintings. For instance the pencil drawn lower left (the viewer’s left) leg can also appear to a kind of phantom of a limb severed at the knee, with the blood-red wound clearly visible. Aesthetic making itself can be seen as such an appropriation of accident or predetermined violence, a making in which the viewer is complicit as Biass-Fabiani suggests:

His drawing is almost always bare and unadorned. There are hardly any identifiable objects or additions and the background is often absent. Rodin concentrates on the human body and it is the body’s vital tension that he seeks to express.[14]

If you can see this exhibition, do. If not the catalogue alone is stunning.

Yours Steve

[1] Nabi, N.A., Ariot, C. & Borchadt-Hume, A. (2021:20) ‘’The Making of Rodin’ in Nabi, N.A., Ariot, C. & Borchadt-Hume, A.(eds) The Making of Rodin: The EY Exhibition, London, Tate Enterprises Ltd.

[2] Jonathan Jones (2021) ‘The Making of Rodin review – not a radical, just a plain old genius’ in The Guardian Online (Tue 11 May 2021 10.00).Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/may/11/the-making-of-rodin-review-tate-modern

[3] Louis Weinberg (1918) ‘ An Essay on the Art of Auguste Rodin’ in The Art of Rodin New York, Boni and Liveright, Inc. The Modern Library of the World’s Best Books.

[4] The quotations in these first two paragraphs are Jones in ibid.

[5] See photographs in Nabi et. al. (2021: 13f.)

[6] Natasha Ruiz-Gómez (2021: 46 – 53) in Nabi et al [eds.] (2021).

[7] Interview with Paul Gselli cited ibid: 52.

[8] Auguste Rodin [trans. by Elisabeth Chase Geissbuhler] (2020: 47) The Cathedral is Dying New York, David Zwirner Books

[9] ibid: 83

[10] all phrases in ibid: 83f.

[11] Anne M. Wagner (2021: 33) ‘ Material Transactions’ in Nabi et. al (2021), 30 – 37.

[12] From: Alfred Tennyson In Memoriam Section LXXVII [“What hope is here for modern rhyme ”] Available at: https://victorianweb.org/authors/tennyson/im/77.html

[13] Rodin (2020: 63) The Cathedral is Dying

[14] Sophie Biass-Fabiani (2021: 39) ‘Bodies Immersed in Liquid’ in Nabi et. al (2021), 38 – 45.

One thought on “‘… far from being spontaneous studies modelled from life, these bodies were made up from a limited number of pieces put together in a diverse range of ways’. We are so used to the lies that idealise the human body in art, life and the links we make between art and life that we forget just why Rodin’s practice as a sculptor matters so much. On visiting the 2021 exhibition at the Tate Modern and reading the brilliant catalogue by Nabila Abdel Nabi, Chloé Ariot, & Achim Borchadt-Hume (editors) ‘The Making of Rodin: The EY Exhibition’.”