‘… even Picasso couldn’t (sic.) escape from his Moorish Spanish makeup ie (sic.) you keep young by having young lovers. It probably works, though I prefer Oscar’s remark that those whom the Gods love grow young.”’.[1] Drawn into life from the dark in an exhibition of early Craxton and a new biography by Ian Collins ‘John Craxton: Art & Life’, London & New York, Yale University Press.

It is arguably a characteristic that the stress on darkness and death in the recent exhibition of works by John Craxton are works which, however they might truly be represented as ‘drawn from darkness’ are those of his early works. The intended pun in the title covers the fact that early Craxton was etched and painted in dark inks and colours over sombre washes while also being as it were ‘drawn out of’ something dark in the adolescence and early youth of John Craxton. That something can, and was by David Attenborough, characterised as war-time Britain and by others as also including the strictures of a particularly homophobic culture. However, even the weather contributed to his sense of malaise as he chose primarily to ‘paint emblematic portraits of himself and his predicament in being held on a besieged island against his will’.[2] Ian Collins, who says this, is responsible for the lovely essay in this volume in which the remark appears but the exhibition was also an informal launch of Collins’ new full-length biography of the painter which stresses the theme illustrated in Craxton’s own words in my title: that Craxton may have grown young. Or perhaps we should say that at least people, including himself, represented him as ‘growing young’ with age. And in regenerate age, art is redrawn in light colours in a medium of tempera in his art too. Even when you ‘wash a darker colour over that’, you ‘get a translucent quality’, said Craxton in a 1951 interview.[3] John Amis, a friend, says (recalling the japes of his ‘youthful abandon’ as Collins calls it) still reserves for Craxton’s older age the judgement that, even then, he ‘would seem to me more of an elderly schoolboy than an oldie’.[4]

Amongst the sources of his rejuvenation appears to be the reaction of his pulmonary health to a move from the climate and pollution and sexual repressiveness of an ‘English summer, where he was ‘breathless and coughing’, ‘confined to bed with mysterious debilitation’ which turned into the signs of ‘youth tuberculosis’. Illness dogged him in London, even on return visits, even when he returned in 1951 to design the sets for Frederick Ashton’s Daphnis and Chloë he was , as he wrote to his possible lover Dino on Poros ‘continually in bed with flue (sic.) and bad cold’.[5] Set against that is a ‘craving … spiritually and emotionally’, for the hot clean dry air of Greece.[6] This would be particularly so of Crete where sailors and other young men were also much more open to take sexual pleasure with other men (as a result in part of Orthodox Church stress on female virginity Collins suggests). David Attenborough insists, in a 2013 catalogue from an exhibition, despite the darkness of early British landscapes that they also show signs of something like Greece, even if filtered though pastoral traditions in poetry and Samuel Palmer’s visual art, pictured as an: ‘escape from the austerities of a war-torn prison to a more relaxed land’.[7]

Indeed in Crete, Craxton came to believe that the ancient palace of Minos, Knossos, was actually the centre of an ancient matriarchal mythology celebrating the return of youthful spring in the persons of daughter Persephone returning to her mother Demeter. Even the climate was marshalled into this magical rejuvenation: ‘The climate of Crete was designed to perpetuate the myth of immortality …’, he said.[8]As I have already indicated this rejuvenation also characterised not only Greek art (literary and visual) but all imaginative forms that fed from the notion of a youthful age encapsulated in pastoral genres, even in the hands of the sage English artists William Blake and Samuel Palmer, from whom Craxton’s work was already turning towards the themes of the Greek diaspora in Sicily as he said of his collaboration with Geoffrey Grigson called The Poet’s Eye in 1944.

… my bias is on the inspired moment with a pastoral leaning. … but I really want to go on holiday to Sicily. The willow trees are nice & amazing here but I would prefer an olive tree growing out of a Greek ruin.[9]

Pastoral art, and thence Greek inspired art generally, was associated with ‘ that timeless air that gives one a chance to breathe & the imagination to work’, as he says in a letter to Joan Leigh-Fermor in Kardamyli.[10] We are out of patience with Romantic notions of the timeless Arcadian themes of painters and poets but for Craxton there was a consistent attempt to ‘root a fleeting moment in a timeless place’ and thus stop the action of Time.[11] Now Craxton knew his Poussin well and the theme in Pastoral that death and time also penetrate the light of Arcadia, as in Et in Arcadia ego by that artist, and for Craxton this was usually associated with Orthodox links between goats and the evils of the timely and of wasting consumption of vegetation. But that theme is not seen as anything but a musical counterpoint to a belief in a place that assists in the preservation, and perhaps the restoration, of youth and the freshness of early days.

In the imagination, the breathless consumptive Craxton knew you could breathe, and this was true too of Greece, and though death and time were present, they were distanced. His early painting Hotel by The Sea shows the reviving effects of colour and pattern that emphasise as Collins says, ‘the physicality of life’.[12] Craxton was not beyond comparing the imaginative vision in art to the ‘timid & Weak & ineffectual’ nature of Sir William Coldstream and his followers which is not only old-fashioned to the young Craxton but ‘so rotten, so decadent, so worthless’.[13]

Now I think Poussin’s point about pastoral in Et in Arcadia ego is taken precisely because Craxton knows that the imaginative vision in which we are rejuvenated is also an illusion, if a beautiful one. He almost mocks – but with true empathy – the tendency of Greek males to narcissistic restraint on aging in their imagination. Greeks ‘regard a portrait as a passport to immortality’ he says as he produces them to make a living: ‘They are in their prime and so they would always remain’.[14] And hence those young men dancing to the rhythm that makes up for eternal youth in his late paintings, even when so brilliantly shaded by disability and a hint of evening in the wonderful Two Figures and the Setting sun (1952-67), where, as Collins points out, one young man shows the common disability afflicting pearl-fishers often from an early age.[15]

Now these themes are still in the beautiful but less well known early works shown in Drawn from Darkness. And they too bring death into paradise. But the dark deathly can be sombre as in this work facing the catalogue title page from the exhibition webpage.

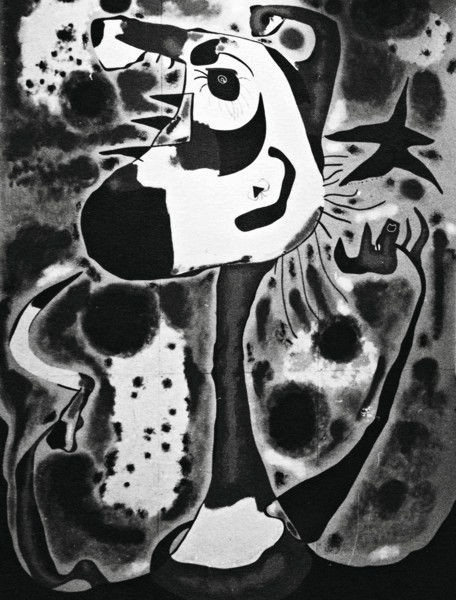

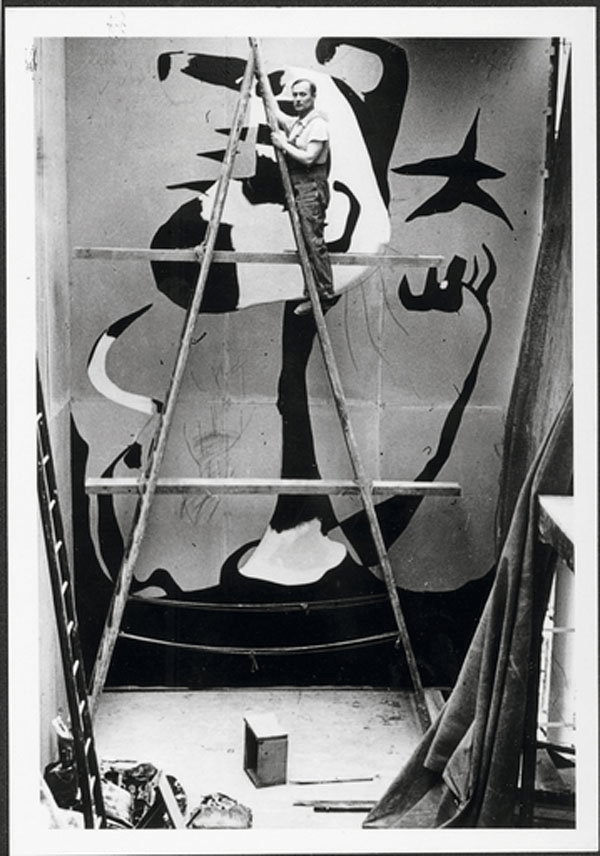

But in other works the theme is even more iconic. It is built into the iconography of the ‘reaper’. He is a pastoral figure enough but associated with death, often at large scale in pre-war Europe. indeed we know that Craxton admired Joan Miró’s wonderful painting which he refers to, having seen it in the Spanish Republic’s pavilion alongside Picasso’s Guernica, as ‘the great painting of ‘The Reaper’ (see below). In it the reaper’s scythe is bloodied in war and the fight of Catalan peasants for justice and equality as well as against Franco’s fascism. Such violence is just but brings death as well as fighting against one of its assistant groups, Franco’s army. There is no suggestion by Collins that Craxton’s ‘reaper’ painting and drawings, so well represented in this exhibition take some of the meanings suggested by Miró, but it feels to me that Craxton was keen to see freedom as a thing worth fighting for, and against Fascism. As Miró says:

Of course I intended it as a protest. The Catalan peasant is a symbol of the strong, the independent, the resistant. The sickle is not a communist symbol. It is the reaper’s symbol, the tool of his work, and, when his freedom is threatened, his weapon.[16]

Surely these meanings emerge in a painting not in the exhibition but seen below from its sale by auction. The dogs that fight are in a different world of militarism and aggressive masculinism that is avoided in the reaper, who still holds his tool of destruction against the dogs’ possessive viciousness.

In the exhibition the 1945 gouache and coloured crayon piece shows a reaper at odds with a world that oppresses him too. There is emotional turbulence that is directed against thorns and weeds but it is also in my view a queer political stance – dark psychologically because of the dark oppression of the time but also strong and decisive politically in cultivating its garden, and eradicating thorns – possibly homophobia as well as other restrictions on imagination in war-time London. This is even more prominent in the 1945 Labourer in a Landscape.

Does this painting echo the Miró, especially in the shape of the outrageous and grotesque growth that seems to stand elevated above the Labourer with its thorns in ways that combine with the climate against the man, who is constantly trying to allow his own figure to emerge from its dark background. This is full of multiplying meanings of political resistance even down to the Catalan headwear. The reaper is almost scraping off darkness, as a jobbing artist would do in liberating image from context of the dark that is the paint surface, in which he might make a free living.

Now where is the light of late Craxton sailors, goatherds and shepherds. It is in the attempt to draw something OUT OF darkness. Collins talks about the importance to Craxton’s theory of art the influence of Graham Sutherland in encouraging a ‘paring back’ of the elements of painting including the paint itself.[17] In the biography Collins also cites a wonderful thought from Craxton about what exactly mattered in Picasso’s Guernica was the removal of all wasted paint. There is a thesis here on how paint and oppression may compare in the psychological politics of early Craxton. I will leave it with you: ‘There is not a line wasted or out of place. And there was no sense of brushwork; I was already aware of the false admiration of “beautiful passages of paint”’.[18] For me, this is about Craxton clearing the space for queer love – space in which his later paintings and young men dance, feast and radiate light through empty space.

This is a wonderful exhibition and a brilliant catalogue and book and I feel much further on than in my own early blog thoughts on Craxton.[19] Let’s leave it there.

Yours Steve

[1] Craxton writing to James Lord from draft of undated letter, cited Collins (2021a:354)

[2] Ian Collins (2021b:11) ‘’Drawn from Darkness’ in Gordon Samuel (ed.) John Craxton: Drawn from Darkness London, Osborne Samuel Modern and Contemporary Art Gallery 6 – 15.

[3] cited Collins (2021a:361)

[4] Cited ibid: 362

[5] cited ibid: 209

[6] ibid: 95

[7] Cited ibid: 124

[8] cited ibid: 181

[9] cited ibid: 119

[10] cited ibid: 299 (undated letter)

[11] cited ibid: 252

[12] ibid: 152

[13] ibid: 112

[14] cited ibid: 155

[15] See ibid: 250f.

[16] Cited by the Tate. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-22-summer-2011/hymn-freedom

[17] Collins (2021a: 13)

[18] Collins (2021b: 40)

[19] See Part 5 of this blog on a Queer Approach to Painting: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2021/05/27/an-old-blog-recollected-a-queer-approach-to-sexual-preference-labelling-in-art-history/

One thought on “‘… even Picasso couldn’t (sic.) escape from his Moorish Spanish makeup ie (sic.) you keep young by having young lovers. It probably works, though I prefer Oscar’s remark that those whom the Gods love grow young.”’. Drawn into life from the dark in an exhibition of early Craxton and a new biography by Ian Collins ‘John Craxton: Art & Life’”