A queer approach to sexual preference labelling in art-history

I am rescuing these pieces from the Open University blog where they were written before they become obsolete there. This is not because of their quality which isn’t great. I a sense they are obsolete. However, I have just seen a wonderful exhibition on Craxton’s early work at Osbourne Samuel, 23 Dering Street, London WC1 and I will refer back to these early thoughts.

They record my autonomous thinking on queer theory whilst on a course that did little on it but to mention it in a rather dismissive way. On top of this they used the label ‘homosexual’ rather glibly and again sometimes dismissively as a ‘limitation’ on thinking – in Winckelmann for instance.

The history of this blog is interesting in that Art History leaders took away my access to adding to it because I was critical of their approach and language on this and other issues. If anything what I learned is that education led by people who want you only to learn what they already know is not education at all.

A queer approach to sexual preference labelling in art-history:1. John Minton

Thursday, 30 Aug 2018, 17:02

Visible to anyone in the world

Edited by Steve Bamlett, Thursday, 30 Aug 2018, 17:09

A queer approach to sexual preference labelling in art-history: looking at case studies in British mid-twentieth century art: 1. John Minton

The aim of this group of blogs is to look critically at some of the publications relating to gay male artists in the mid-twentieth century. This is in part to begin trawling for a dissertation topic for my MA in Art History. My initial thoughts relate to focusing on one of these artists, although their contexts include each other, their treatment of male nudes in relation to the iconographic, contextual and stylistic features which propose such a subject for art (for some of the choices this will include photography as well as painting) and ‘queer theory’. This will look at the issue of labelling of course, particularly at the important terminology of ‘homosexuality’, which dominated the period. My hypothesis will probably be that such a term was, and remains, a means of marginalising, even to the point of negation, of such art. My probable choice of artist at this stage is probably Keith Vaughan, although my reading has just begun. My interest though was sparked by Mark Gattis’ splendid programme on John Minton shown recently on the BBC.

Frances Spalding re-issued, with ‘revisions’, her 1991 book on Minton in 2005[1], counting as most significant of the advances made in the literature since 1991 Hyman’s book on figurative art. However, unlike Gattis, she does not revise the terminology of her first edition with regard to sexual categories and the categorisation of sexual personae, which in 2005 (the year gay marriage was – from December only first made legal) meant that her statements on the subject again relied on her 1991 ‘Introduction’. This gives a taste:

… his fascination lies not only in his gaiety, generosity, creativity and wit, but also in the melancholy, disaffection, and despair that at times showed so clearly in his face. To reduce this man to an untroubled symbol would be manipulative and demeaning. It would also do little to increase the understanding of homosexuality.’ (3)

Whilst well-meaning, it is clear that it is difficult not to equate ‘homosexuality’ with the aetiology of a negative mind-set. It is clear too, in the whole book at least, that Spalding sees the ‘homosexual’ as the ‘subject of discourse’, where discourse is neither owned, controlled (even as a participant in discourse) by the ‘homosexual’. At one point she even characterises the difference between bisexuals (and self-defining heterosexual men willing to give it a go like Alf Sparkes) by naming Minton by the old-fashioned (even in 1991) but no less objectifying and marginalising term ‘invert’. The category of the ‘homosexual’ is defined external to persons, as a ‘subject’ that has the universality that Cartesian discourse itself allows it as an element in discourse. We need to ‘understand it’ but the subject that understands it remains a non-specified and non-particularised ‘subject’ that pretends to be neither male nor female, gay nor straight. It did not need Foucault to show us that such a subject was in fact constituted through power with the ability to define the difference between norm and ‘other-than-the-norm’ as part of that understanding.

We need to puzzle over some of the ways Minton’s cognitive-emotional-sexual life is presented to us. He did not ‘like’ homosexuals we are told (an issue that will arise again with Vaughan). He wanted the love of a ‘real’ man. These are not idiocies – I remember feeling them with all the pain they involved but they are prime examples where, as Paolo Freire shows, the ‘subject of discourse’ is ‘subjected’ to the power of norms that are actually the product of multiple other structures of power: majority status, ownership of cultural symbols, or enhanced visibility through symbols, for instance. They enforce that splitting of the person from which no gay man or lesbian was immune, whatever the claims made – often blowzily (‘I Am What I Am, and What I AM Needs No Excuses). If I am what I am, I am myself and other.

That is how Minton fed his self-loathing, projected onto other gay men and his preference for an extreme and aggressive maleness in his lovers, even to the point of invited violence (223). Of course, not that gay men and lesbians needed to ‘invite’ violence: it came uninvited as a means of people differentiating their normality from that which is (self-evidently it seemed) different and ‘odd’. I have no doubt that it is these structures of feeling, fed by structures of societal and ideological power, that exclaim Minton’s divided self in relationships, his ambivalence to the maleness in his lovers that he encouraged, even to the ‘provision’ of ‘women’ for them (when one of his lovers Kevin Maybury took on an older male lover, Minton went into a deep depression (236). We can infer that this was because this circumstance broke the tragic paradigm which explained ‘homosexual’ relationships to him and was thence unprepared for by the myth of the ‘homosexual’ (Maybury was the only one of his lovers who was predominantly gay and though a carpenter, was one who worked on stage in a theatre). It also explains his, and other middle-class gay males preference for lovers who were evidently less socially, intellectually ‘valued’ than they themselves were. It justified treating these young men (the ubiquitous sailors and guardsmen (and, it has to be said, students) in Minton’s life) as objects and predicted him finding them lesser than his normative self. We see this in E.M. Forster too but he seemed to find intelligence in his working-class lovers (the policeman Bob Buckingham for instance) as he aged.

But none of this is that clear to Spalding, who nevertheless clearly heaps maternal love on the poor boy of her biographical treatment. It feels to me that she therefore fails to understand the relationship (as artists and gay men) between Minton and Keith Vaughan, who became housemates. Their relationship was built on very different constructions of the relationship of art to homosexuality and the homosexual they were persuaded to see and distance themselves from in themselves: the former focused on necessitated but spiritualised tragic loneliness, the latter on a kind of Dionysian uniqueness, that enjoyed persecuting the vulnerable bit of the self just as social mores seemed to do. Both committed suicide but the differences therein also illustrate differences in their construction of their queer selves, the one based on a romantic (see Sleeping Figure (1941) & Landscape with Figure (1944) both of which remind me of David Jones as well as John Craxton) and the other on objectified visions of the male body that do male figures which, even more radically, Picasso does to female figures like Marie-Therese. But more on this in the Vaughan summary.

Minton might under different tutelage (had for instance he succeeded in splitting up the Two Roberts and involved himself with Robert Colquhoun as his aching heart longed for (since Colquhoun mastered extreme male roles as a gay man).

Yet I like both great paintings of Norman Bowler very much (Plates 18-19 in this book: Painter and Model (1953) and Portrait of Norman Bowler (1952)), which feel to me to have learned from Bonnard how to use painter and model with full consciousness of the role of both framing subjects in complex multiple contexts and the use of perspective to focus on what is meant by the sexual male. Gattis’s view that these techniques over-emphasise the domain of the male groin is, I think, only part of the story because at the same time embodied sexuality is cast from the foci of that domain by the fore-fronting (almost to the picture plane) of naked hands and feet. Minton’s men are more men when, in his great illustrations they form idealised working (and often working-class bodies).

If I am correct about this use of framing, this backs up in part Spalding’s reading of that wonderful Portrait of Kevin Maybury (1956)[2] in which she picks up the role of stage-setting tools, as well as easels and floorboards as ‘trapping’ Maybury (220). For me he is trapped but also the artist’s model framed in the act of manipulating the frames in which he is held by manipulation of the folding ‘ruler’ that governs all built frames – the architectures of stage and painting. Stage carpenters do that anyway. Isn’t this a wonderful picture though? One I would say is genuinely queer – escaping the constraint of the medicalised and marginalising label ‘homosexual’.

All the best

Steve

[1] Spalding, F. (2005) John Minton: Dance Till the Stars Come Down revised 1991 edition, Aldershot, Lund Humphries.

[2] Tate Gallery website – John Minton page https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/john-minton-1644

A queer approach to: 2. Keith Vaughan, artist

Monday, 3 Sep 2018, 17:16

Visible to anyone in the world

Edited by Steve Bamlett, Monday, 3 Sep 2018, 17:32

A queer approach to sexual preference labelling in art-history: looking at case studies in British mid-twentieth century art: 2. Keith Vaughan

The aim of this group of blogs is to look critically at some of the publications relating to gay male artists in the mid-twentieth century. This is in part to begin trawling for a dissertation topic for my MA in Art History. My initial thoughts relate to focusing on one of these artists, although their contexts include each other, their treatment of male nudes in relation to the iconographic, contextual and stylistic features which propose such a subject for art (for some of the choices this will include photography as well as painting) and ‘queer theory’. This will look at the issue of labelling of course, particularly at the important terminology of ‘homosexuality’, which dominated the period. My hypothesis will probably be that such a term was, and remains, a means of marginalising, even to the point of negation, of such art. My probable choice of artist at this stage is probably Keith Vaughan, hence this blog is a start in a later reading project.

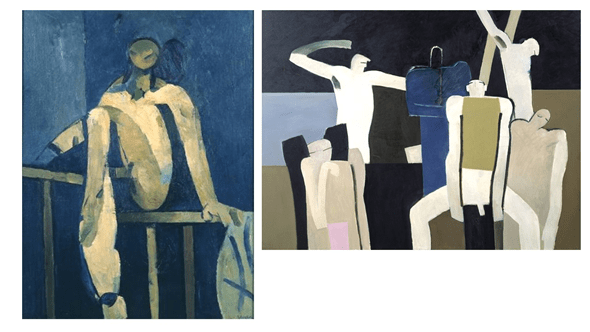

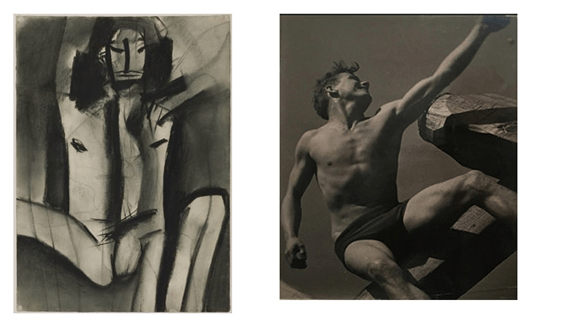

Frances Spalding’s (2005:3) biography of Minton is not a fair basis of comparison with Vaughan and that partly because her biography is apparently aiming for an ‘understanding of homosexuality’. Malcolm Yorke’s (1990) excellent biography of Vaughan makes no such claims and merely charts the artistic, social and sexual life of Vaughan (and the impact upon that life of contemporary constructions of homosexuality, including those which Vaughan intermittently internalised). It is less motivated by attempts to ‘understand’ on the basis of a limited case-study and a belief that the term ‘homosexual’ is ontologically valid. In short, here, the essence of what the ‘homosexual’ might be is neither defined nor imposed as a definition of a part of an assumed reality. Indeed I don’t think the term is validated. In this respect Vaughan’s book makes a much easier step towards a queer reading of mind-twentieth century reception of ‘scientific’ and medicalised discourse on homosexuality. Such a reading needs to explain the methods of his public art as well as his private erotica, such as The Leaping Figure here.

Vaughan himself, like Minton, felt ambivalence about ‘homosexuals’, which he projected as an ambivalence about other gay men (together with an ability to exploit and diminish those he came into sexual or social contact) and introjected as a, in his case, almost virulent self-hatred. Vaughan’s campaigning journals show a tendency to prefer a sexuality which crossed more than normative sexual practice boundaries, exploring the potential of sex as an onanistic science dependent on machines and inanimate objects. When people were involved, he chose even more obviously less powerful personalities as his partners whom he could belittle and hate (although often only privately in his journals as his partner, – as near as he ever got – Ramsay McClure, found to his cost). But he also romanticised and loved these same people in the moment, without any necessary recourse to ever seeing their personhood, often using their marginalised status (and often their poverty as in the case of his young Mexican lover) as the basis of such Romanticism. Eminent amongst these was Johnny Walsh (166f.). And herein lies a conundrum. Unlike Bacon, who seemed to feel no great visible responsibility to working (and criminal and indigent) class – I’m not sure the distinction was ever made in these haute bourgeois English artists – partners such as George Dyer, Vaughan also attempted to become paedagogos (for a time) to Walsh, whom he often characterised as a kouros.

These dynamic relationships of projection of the lesser and introjection of the ideal in the end allowed Vaughan to see himself as unlike other ‘homosexuals (not camp like Isherwood and Minton) but ‘special, unique (47).’

These contradictions do not exemplify, as it was sometimes thought at the time (by E.M. Forster for instance right into a privileged old age) homosexual love, they are (I would argue) distortions caused by the ways in which heteronormative values assumed the qualities of the ‘natural’ ideal of sexual life. Hence the liberation involved in ‘queer theory’ which looks at how that which lies outside the supposed and ideological norm (often practices in real life that are silent or silenced by ideology) survive nevertheless. Looked at from this perspective, Vaughan’s queerness looks very like that that of Picasso – both based on giving primacy of artistic solutions to problems experienced in the human sphere of activity, especially those of sexual love.

Vaughan theorised homosexuality obsessively (even to the extent of a totally forensically objective definition of the material ‘symptoms’ of love as a kind of necessary psychosis (234). I think he was correct to see ‘homosexuality’, as it was defined in the theory of the time as a category tied to constraining and marginalising social roles, the ‘other’ to heteronormativity. What he failed to see (unsurprisingly for the time when his sexual life may have led to long-term imprisonment or chemical castration) was its socially-constructed nature. He lived long enough to despise ‘Gay Lib’ for ‘flaunting itself in the face of the public (cited 254)’ (as if what is public were only heteronormative). He tended to use the distortions of Freudian theory (which he contacted mainly through secondary texts) to see even his own ‘homosexuality’ – if not his sexuality as a whole – as a form of immaturity, one that he had not achieved on the route to heteronormativity: ‘I have regressed even from the immaturity of homosexuality to an almost pre-natal infantilism (cited 237).’

Of course there is much to say here that I want to leave in silence (for now) because its importance for me at the moment is the way in which a queer approach to Vaughan’s art rescues the artist from the time-bound and limited thinker of the journals. That mass of contradictions (the Journals and Vaughan as a biography) matters and helps with the art but does not show his importance. For me this comes from his rethinking of the traditions embodied in the male nude trope – one that Vaughan saw has predictable from his homosexuality (197) but as essentially contributory to a breakthrough in artistic technique (technique he taught at Slade as before (198) in terms of the primacy of painterly composition and pioneered in art in the practice of ‘assembly’ paintings (200) – as in the Ninth Assembly of Figures here, which he saw as classical in form if both classical and romantic in subject. He was devastated when he discovered that the basic invisibility of Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling male nudes (which he thought validated those fusions) could not be ‘seen’ from the chapel floor and therefore could not have (he felt then) created a tradition (230).

Yet tradition there was – one, though I’m still working on it, I would call a queer tradition that amalgamated various sources that were not equitable with homosexuality nor with any directly intended expression of male desire for ocular evidence of other male bodies (sexual or not): this tradition included the academic tradition of the male nude and the male nude considered as emblematic of idealised proportions of form and style. Both owed something to Winckelmann’s readings of the classical and Renaissance tradition (including Raphael and Michelangelo), to Neo-Classicism and the function of the Academies in Europe (including Britain, in the work of William Etty in the nineteenth-century) which also fed off Winckelmann, although now mixed with its apparent opposite, Goethean romanticism. However, the most formidable model, especially for the reformulation of a notion of what we might mean by the classical nude is Cezanne, Vaughan’s key model for his male nudes in public painting. Yorke (1990:40f) summarises thus how Vaughan felt he honoured the classical forms in Cezanne in his own painting, something with which I fully concur:

Structure was imposed on the teeming chaos of reality by eliminating unnecessary detail, simplifying trees to masses …, suppressing any individuality in bathers’ faces or bodies, and simultaneously making every part of the picture conform to an underlying geometrical structure, distorting forms to this end if necessary. (And more)

I too hope to say more of Cezanne’s male nudes when I write in earnest, since their reception has historically been mediated through a thick varnish of homophobia which refuses to see desire in them lest it taint an ideal Cezanne. Cezanne did not need to be ‘homosexual’ to reinvent the male nude as both classical form and romantic icon, I’ll argue. Moreover, we need to take this classicising even of the most romantic and desire-imbued forms seriously in Vaughan. If his public paintings became impervious to gay male desire in favour of some other sublimation (I think he possibly saw it in those Freudian terms), it is not just because this would ‘give him away’ in the deeply homophobic British twentieth-century up to the 1980s but because he felt there was a difference between the artist (even the queer artist’s) conception of the male nude in art to that serving purposes of sexual excitation (as explored by Lucie-Smith in different terms (1991:8). Indeed I think Vaughan drew male nudes in 3 different arenas and for 3 different functions, becoming more aestheticized as they moved away from extremely secreted pornography on the first level (Hastings 2017), semi-private eroticism in subjective inter-relationships (Vaughan 1966, Graham & Boyd 1991) and ‘fine art’. The latter had no obvious sexual organs, a number of means of erasure being followed very consciously.

In the latter category bodies are as he intended them following Cezanne’s example (and a reading of trans-historical painterly classicism) such as they example queer art but not art confined to categories like ‘homosexual’ or even ‘gay’ art. It was queer because it still included a formulation of desire in composition, and, at times, Vaughan believed, in ways that could not escape contradictions that exposed art to eruptions of personal desire and which made him see even his art, perhaps all great art, as an expression of ‘homosexuality’ rather than the queerness of desire, which is now visible as nearer to the truth. He wrote in his journals in the 1960s (Yorke 1991:197):

… pages of speculation about how the majority of the great painters of the male nude were homosexual: … how the previous night he, like the Virgin in Michelangelo’s Pietà in St. Peter’s, had held a youth called Mike naked in his arms in the exact pose of the Christ.

We need to see, more clearly than Vaughan here, what queers the representation of the male nude, probably trans-historically, without silly identifications of gayness or homosexuality before those terms had meaning.

Looking at say the 1970 male nude below, I’d assert that Vaughan’s public art is better than Lucie-Smith (1991) asserts, blaming as he does the heteronormativity and homophobia of the times, and that it was not marred by repressed instincts (to fuller sexual expression) but dug deeper into what the male nude represented homosocial (rather than just homosexual) meanings. Hence his interests in male archetypes: Kouroi, Crucifixions, warriors and noble assemblies. His male figures sometimes emerge from an early set of his photographs from Pagham Beach and there are real similarities between our last mentioned illustration and this one from Pagham.

Pagham pictures included young men whom he related to very differently, including his beautiful (and heterosexual) brother, Dick (an unfortunate name sometimes). We need to see Vaughan though as artist not as repressed homosexual – queer theory allows that – and we then see that these male nudes are very complex icons, or at least that is what I’d like later to assert.

All the best

Steve

A queer approach to 3. Christopher Wood

Tuesday, 4 Sep 2018, 20:01

Visible to anyone in the world

Edited by Steve Bamlett, Thursday, 6 Sep 2018, 08:49

A queer approach to sexual preference labelling in art-history: looking at case studies in British mid-twentieth century art: 3. Christopher Wood

The aim of this group of blogs is to look critically at some of the publications relating to gay male artists in the mid-twentieth century. This is in part to begin trawling for a dissertation topic for my MA in Art History. My initial thoughts relate to focusing on one of these artists, although their contexts include each other, their treatment of male nudes in relation to the iconographic, contextual and stylistic features which propose such a subject for art (for some of the choices this will include photography as well as painting) and ‘queer theory’. This will look at the issue of labelling of course, particularly at the important terminology of ‘homosexuality’, which dominated the period. My hypothesis will probably be that such a term was, and remains, a means of marginalising, even to the point of negation, of such art. My probable choice of artist at this stage is probably Keith Vaughan, hence this blog is a start in a later reading project. This blog goes back in time to examine Christopher Wood (1901-1930), one of Sebastian Faulkes’ ‘Fatal Englishmen’.

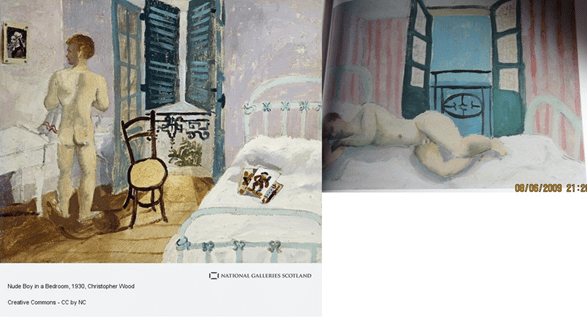

I first discovered Christopher Wood’s now classic ‘Nude Boy in a Bathroom’ on visiting the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art[1] where it forms part of the permanent collection. Only since working on Wood, have I discovered that there are at least two preliminary studies or companion pieces. In the one not shown, which I have never seen reproduced, the model stands facing the viewer frontally (Cariou & Tooby 1997: 53)[2].

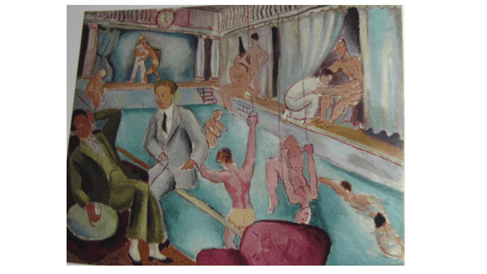

However, before looking at these pictures, completed in the year of his possible violent suicide, it’s important to see how and why Wood’s case is particularly suited to a queer theory approach. Extant criticism known to me plays games with labels – dubbing Wood ‘conveniently bisexual’ (whatever that means, it was said by novelist Anthony Powell cited Norris 2016:28[3]), mainly homosocial if sometimes homosexual, repressed gay man or an innocent perverted by a rich European homosexual clique or even the Parisian art-scene (perhaps especially Cocteau)). All of these labels come with some peculiarly nasty imposed value sets which reduce Wood to something lesser and stop us looking at his intriguing but very queer painted surfaces (even ones apparently not so such as Dancing Sailors, Brittany (1930)). Wood painted some very sensual female nudes and had several sexually consummated love affairs with women and he idealised the married love of Ben & Winifred Nicolson, although its bitter end was in sight before he died.

However, he also created some images that are inescapably ‘gay’, although I do not include his last male nudes in this number. Compare, for instance, Exercises (1925) and his portrait of Constant Lambert, Composer (1927), a gay icon of the period working with Diaghilev, helping to produce performances which revelled in the male body.

These pictures need no comment. They both record, and perhaps, in the case of Exercises comment, on the issue of homo-eroticism in ways that also participate in it at the ocular level. In as far as art sublimates desire in these pictures, it does so at a very shallow level (the composer’s pen and violin being conveniently phallic and placed in a way that advertises the substitution being made).

But next to these in this short career we could place images that appear to create a heterosexual fairy-story (such as The Bather (c. 1925-6) which bristles with phallic symbols surrounding the female semi-nude) or the more sentimental pictures of family deriving from Wood’s experience of the Nicholson marriage at St. Ives (the lovely The Fisherman’s Farewell (1928) for instance).

Queer theory sees no point in ‘seeking the homosexual’ but rather sees the various performances of diverse sexualities as to be expected and in no way in direct relation to an artist’s essential being. Wood then is its ideal subject. We can stop now trying to see if his relationship to the diplomat, J.A. Gandillaras, was predominantly homosexual or homosocial

In my view the Nude Boy in a Bedroom (1930) is best examined using queer theory. It is, of course, probably necessary to report that it is usually thought that the nude boy is a portrait of Francis Rose (about 21 at the time), friend of Gertrude Stein and Toklas (the latter’s Cookbook illustrator) and, at this time, visiting Brittany alongside Wood and gossip says ‘a noted homosexual’[4]. It is set in what we believe to be Wood’s hotel room. But that aside, it is not a ‘sexualised’ scene. The ginger-headed boy at his morning ablutions (we can see by the strength of the penetrating sun it is morning) turns from his sink and towel (the latter still in his hand) to gaze at a picture of a Breton maiden. On the bed lie three Tarot cards – the same ones appear in Calvary at Douarnez (1930) and predict, Norris (2016:153) argues, ‘financial and romantic insecurity, as well as alluding to danger.’ Nothing in the picture makes us conscious that the ‘boy’ is aware of being seen. This picture bears nothing of the portrait of Lambert above. It cannot be described as homoerotic (although it is, I would say, homosomatic).

Yet if not ‘homosexual’ in orientation it is definitely queerly homosocial. A man gazing at a woman is being gazed at. There is kind of liminal sensuality about the bedroom and we notice the soft edges of this body, defined only in the display of the right buttock. The room is partially darkened by shades but where it is not dark, where the boy isn’t, a queerly distorted chair is on display and brandishing Wood’s favourite ‘yellow’ (a colour he felt only great artists handled well). This boy is neither ready for nor certain that he wants the light of day to make himself known by. And the feminine shapes of the metal balcony and the bed show a boy who may find it difficult to step up to be a ‘man’. All this unsettles – is this boy’s nudity innocent or erotic or neither? Is he unwilling to take a seat or to stand in the light? Are we tantalised by that, whatever our own sexuality or gender-position as viewers? The smeary browns in which the boy stands disturb and clash with the pastel shades of white, green and purple (on the walls). We wonder at the half-open shades. Has he stood there to partly open them? Whose view does he disturb?

As you can see, I am a long way from getting past open questions on this one, but Wood disturbed Minton and Vaughan too, I am sure. And this is very suggestive about the open-endedness of the male nude to queered vision.

All the best

Steve

[1] https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/artists/christopher-wood

[2] Cariou, A. & Tooby, M. (1997) Christopher Wood: A Painter Between Two Cornwalls (text by Steel-Coquet, F.), London, Tate Gallery Publishing (for Tate St. Ives)

[3] Norris, K. (2016) Christopher Wood London, Lund Humphries & Chichester, Pallant House Gallery

[4] https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Cyril_Rose

A queer approach to : 4. The Two Roberts (Colquhoun and McBryde)

Wednesday, 12 Sep 2018, 08:37

Visible to anyone in the world

Edited by Steve Bamlett, Wednesday, 12 Sep 2018, 08:40

A queer approach to sexual preference labelling in art-history: looking at case studies in British mid-twentieth century art: 4. The Two Roberts (Colquhoun and McBryde)

For contemporary footage, as well as access to the companion exhibition curated by Patrick Elliott see this wonderful short video.

The aim of this group of blogs is to look critically at some of the publications relating to gay male artists in the mid-twentieth century. This is in part to begin trawling for a dissertation topic for my MA in Art History. My initial thoughts relate to focusing on one of these artists, although their contexts include each other, their treatment of male nudes (or not in this case) in relation to the iconographic, contextual and stylistic features which propose such a subject for art (for some of the choices this will include photography as well as painting) and ‘queer theory’. This will look at the issue of labelling of course, particularly at the important terminology of ‘homosexuality’, which dominated the period. My hypothesis will probably be that such a term was, and remains, a means of marginalising, even to the point of negation, of such art. My probable choice of artist at this stage is probably Keith Vaughan, hence this blog is a start in a later reading project. This blog covers two men, often thought of as a unit and sometimes as a trio. It is critical thought based on reading Elliot et. al. (2014)[1].

First of it is important to see that the work considered here includes no extant male nudes and that moreover clothed figures are often labelled (although not always) older lower-class (or peasant) women, although both women and men have an androgynous look. Many see self-portraits in pictures, especially by Colquhoun, of duos. I do not see the gender boundary-crossing here as either defensive (avoiding identification of a gay subject-matter) nor as mere transposition. Instead, it is clear that gender identity is throughout presented under a cultural sign of acting, masking and performance. In that sense, the two Roberts are nearer to queer and performance theory than any artist I have looked at. Their lives however intersected closely at times with both Minton and Vaughan.

But I also think that the Two Roberts cannot be used as the stuff of rescued homosexual icons. Their relationship to discourses of homosexuality is less evident, if there at all, than in Vaughan or Minton, and other, more political identifications present, however abstracted in their form and activity in their lives, based on their working class and Scottish origins. The two Roberts were known to Hugh MacDiarmid (if only as the ‘wild Scottish artists’ in The Company I Kept) for instances and had defined views of Scottish nationalism and politics on the left, with regard in particular to dispossession and loss.

It seems to me too that their imagery, especially in as far as it relates to the ‘mask’ is under-researched. I am particularly interested in the difference in facial masks between the two, which seem to me adverted to in the theme of Colquhoun’s wonderful monotype, Mother and Son (1948).

There is too much here for a useful summary blog. However, here is art that would respond to queer theory. Far from trying to derive a narrative of the two Roberts from the pictures, it would be useful to look at how they produce images that queer relationships between figures that forefront acts of representation (mimetic and symbolic) themselves and their assumptions. My feeling is they do this with thought about shadows, reflections and framing – perhaps even framing. An influence here could be Hogg. When we deal with Scottish art – expect that difference!

The blog has done for me what I required for myself – opened up some questions, so I’ll stop there.

All the best

Steve

[1] Elliot, P., Clark, A. & Brown, D. [Eds.] (2014) The Two Roberts: Robert Colquhoun & Robert MacBryde Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland.

A queer approach to: 5. John Craxton

Thursday, 13 Sep 2018, 19:06

Visible to anyone in the world

Edited by Steve Bamlett, Thursday, 13 Sep 2018, 19:11

A queer approach to sexual preference labelling in art-history: looking at case studies in British mid-twentieth century art: 5. John Craxton

The aim of this group of blogs is to look critically at some of the publications relating to gay male artists in the mid-twentieth century. This is in part to begin trawling for a dissertation topic for my MA in Art History. My initial thoughts relate to focusing on one of these artists, although their contexts include each other, their treatment of male nudes in relation to the iconographic, contextual and stylistic features which propose such a subject for art (for some of the choices this will include photography as well as painting) and ‘queer theory’. This will look at the issue of labelling of course, particularly at the important terminology of ‘homosexuality’, which dominated the period. My hypothesis will probably be that such a term was, and remains, a means of marginalising, even to the point of negation, of such art. This blog develops some ideas around the work of John Craxton.

Craxton did not paint nudes as part of his public, nor, as far as I know, private, subject matter in art. This may be significant. His young men are always clothed and follow certain ‘simple’ types, a kind of Continental version of ‘Shropshire Lads’, though characteristically shepherds, goatherds, sailors and young working men dancing in Greek tavernas. These have a kind of stereo-typicality about them, even when they could be said to be based on realisations of his fantasy life. He loved the bars frequented by sailors from Souda Bay, conveniently near Chania. He smiled when the supporters of the fascist colonels reported him as a spy because an educated Englishman who loved sailors’ bars was thought to be, of necessity, interested in military intelligence.

This suspicion by some Cretan neighbours led however to one of his rare politicised actions: abandoning Fascist Greece until the fall of the colonels. His favoured genre though was pastoral, and pastoral is only ever indirectly political and at the level of a generalised iconological practice. And pastoral represented his insistence on idealising – Greek males in particular, such that the violent family blood feuds he knew of in Crete never get even suggested in his art, the only threat posed by his subjects being their luxurious and irreversible eating up of what is good and which sustains – like the goats he shows picking the last fig leaf of an isolated tree in a beautiful landscape (my favourite being Goat, Sailor and Asphodels 1986, a consciously iconographic work).

Pastoral in Craxton is hopeless beautiful and hopelessly flawed. His young men are as radically unreal as is the island itself at the level of his wishes, and, in a favoured icon of young men thrashing octopi, with a ruthlessness in their passion:

An island where lemons grow and oranges melt in the mouth and goats snatch the last fig leaves off small trees the corn is yellow and russles (sic.) and the sea is harplike (sic.) on volcanic shores saw the marx (sic.) brothers in an open air cinema and the walls were made of honeysuckle

Craxton hated the novel (and film) Zorba the Greek as being too critical of Greek country people, sailors and their character.

John Berger once tried to see the bare feet that characterise these young men as a hint of political realism, a subtle politics, but they equally act as an emblem of the naked essence of the men. They are often focused upon at the cost of massive distortions of the figure and its place in the landscape, or patterned as the emblem of masculine togetherness in dance. The examples are complex and not clear icons of attraction, though they approach that. Examples are Figure in a Grey Landscape 1945, Greek Fisherman 1946, Galatas 1947, Pastoral for PW 1948, The Dancer, & Two Greek Dancers 1951, Shepherds near Knossos 1947, Boy on Wall 1958, Workman III 1961, Voskos II 1984, Two Figures And Setting Sun 1952-67.

Craxton was a painter of queer pictures but I think he, unlike other case studies here, could be comfortable with the category of the homosexual which he could equate with Orpheus at the mythic level and the sexologists’ category. It did not stop him seeking marriage with Margot Fonteyn (but it didn’t get far) but it did stop him from using his privileged position to facilitate a gay lifestyle in a Britain that became increasingly oppressive for many of the unprivileged. Arcadia was gay and it lived in Greece, and latterly just in Crete. But his shepherds have complex desires. Collins (2018:181)[1] traces them all to a common type made up of complex private iconographic meanings but focused on friendship and George Psychoundakis the Cretan shepherd and Patrick Leigh Fermor’s Runner and dear friend, the ties with whom were not remotely sexual. Yet, despite this, using Craxton’s biography would go none of the way to understanding his art. Let’s take Still Life with Three Sailors, which he worked on (with variation) from 1980 – 1985.

Craxton’s friend, Patrick Leigh Fermor, traces the roots of the painting (cited Collins 2011:151) [2] to Byzantine icons of the visit of three angels to the house of Abraham. The largest version (ibid: 153) focuses on an empty chair at the picture plane occupied by the sailors’ caps, one labelled for the Greek Navy ship, Kriti (Crete). This empty chair is provocative – it is occupied but inviting (perhaps I get that from the way the abandoned fork lies in what looks like a plate of stuffed peppers). Craxton may be semi-present here, not least in the untipped cigarettes packet, labelled with his own name in Greek characters. In the last version it is part of what Leigh Fermor calls a pattern of wandering red in the picture – more prominent and modulated in this version than others by virtue of pink light patterns on the floor. In the trio the youngest sailor seems picked out from the rest, his arm spanning the table and his face lost in green shadow. He alone might look up to see the viewer and is the only one not given entirely to drink and thought.

Whatever it might mean, its iconography is private but it clearly focuses on desire, memory (a nostos painting to Leigh Fermor) and appetite. And there is the menace of the warning to the sailors to avoid breakages in any onset of post-prandial plate-smashing. It is most delicate, though tough and in it lies, I believe but I have not got there yet, something that is not ‘homosexual’ but is queer, a desire and appetite that momentarily floats free. This needs more work but it would unite it with the complex of appetites in numerous paintings of cats, trees and birds and their patterned, and labyrinthine, connections to each other.

All the best

Steve

[1] Collins, Ian (2018) ‘The Later Years: John Craxton’ in Arapoglu, E.. (Ed. trans. Cox, G. & Johnston, P.) Ghika, Craxton, Leigh Fermor: Charmed Lives in Greece, 3rd Ed. Nicosia, A.G. Leventis Gallery, 179 -186.

[2] Collins, Ian (2011) John Craxton London, Lund Humphries

A queer approach: 6. Reflecting on Edward Burra through new material from Minton

Friday, 21 Sep 2018, 19:12

Visible to anyone in the world

Edited by Steve Bamlett, Friday, 21 Sep 2018, 19:29

A queer approach to sexual preference labelling in art-history: looking at case studies in British mid-twentieth century art: 6. Reflecting on Edward Burra through new material from Minton

The aim of this group of blogs is to look critically at some of the publications relating to gay male artists in the mid-twentieth century. This is in part to begin trawling for a dissertation topic for my MA in Art History. My initial thoughts relate to focusing on one of these artists, although their contexts include each other, their treatment of male nudes in relation to the iconographic, contextual and stylistic features which propose such a subject for art (for some of the choices this will include photography as well as painting) and ‘queer theory’. This will look at the issue of labelling of course, particularly at the important terminology of ‘homosexuality’, which dominated the period. My hypothesis will probably be that such a term was, and remains, a means of marginalising, even to the point of negation, of such art. This blog looks at some reflections on

Reading this by Minton pulled me up short:

I may never paint a picture that will survive for in it is that weakness, lack of incisiveness which characterises all the self expression of homosexuals, but to paint it is inescapable.[1] (p.9)

For that is at the heart of a problem to explore. For Minton, being a ‘homosexual’ was the cause of his failure to produce great art and is here made equivalent to the same kinds of reason to which his suicide is sometimes (wrongly, I believe) attributed. The question should not be one of identity but of labelling and of the constraints in self-definition and self-expression this involves. For Minton, language being what it is, this state of weakness was equated with the word ‘queer’ too, used as a word of labelling Abuse.

Queer theory attempts to look at ways in which destabilised norms (not just sexual ones) allows open up our assumptions about the normal and fracture the ideological glue that holds them together. It may be that, for Minton, holding notions of self that inbuilt weakness were precisely the source of his indecisive ambiguities, in that he saw them not as a strength that exposed the constructions of the symbolic world but as a characterisation of self as other, weak to its strong stability. That Minton could be a wonderful painter, worthy of survival is shown I think when he began to paint men of other cultures. Simon Faulkner (cited Martin 201b[2]:63) argues that these images succeed because of the painter’s ‘avoidance of the overt queering of the black male body’. In fact Minton did not overtly queer any other male bodies, although, of course Burra did do so with all the bodies in his early art. Minton’s is in producing images of desire that queer his entire picture – that stop us making easy assumptions about identity or relationship in his most successful (and some less so) male figures and opening up potential.

So perhaps we need to look briefly at Burra via Martin (2011)[3]. Although it is true that there is overt queering of the white and black body in Burra, it is not always straightforward in its picture of desire – nor do I think it makes a virtue of labelling its figures or overall meaning ‘homosexual’. His great picture The Straw Man (1963) surely shows this, in ways it would be difficult to explain in few words, so I’ll use that as an excuse to leave it there.

The Straw Man (1963) Pallant House Gallery (on loan from private collection). Available at: http://www.culture24.org.uk/art/painting-and-drawing/art366630

In less great pictures, there may be a case for seeing ‘overt queering’, often using very obvious stereotypes, such as the sailor (see Three Sailors at the Bar 1930 & Dockside Café 1929). Yet even here there are complexities in which turn some signs of homosexuality (such as rings or the colour ‘pink’ in the 1929 painting) in on themselves in my view. These points need arguing but this is not the point of the blog per se. That is, to say that the weakness of ‘queer’ figurative art and the association of its key figures with suicide are not symptoms of ‘homosexuality’ (whether that oppressive term is considered as a medical-disease terminology or not in any part of its recent history) but of the norms, whose power queer art at its most successful overturns – both in its mimetic representations and compositional character. Let’s say it, Straw Man is a picture about liminality – desire turned violent in which the aesthetic, the meanings and the limbs of figures are all queered by contradictions and uncertainties. I think this is true of the early art but also true of the later non-figurative landscapes in which boundaries take on liminality and no road is ever ‘straight’ nor its determination known.

My first Burra painting (in terms of seeing an original) was the haunting Near Whitby, Yorkshire (1972), where meaning, shape and colour are all queered in ways in which destabilises (most gratifyingly) that most ideological of terminologies – of ‘nature’ and the ‘natural’. This is done too in in his 1971 pointing Snowdonia No.2 where forms themselves are liminal between mist and apparition too, but too obviously and pointedly. The Near Whitby painting just ‘haunts’ and is more successfully Gothic than any of his less satisfying (excluding his wonderful Don Quixote set sketches and theatre furniture) fantasies from the 1940s.

In truth, Burra too is about unpacking and then discarding the term ‘homosexual’. It is too queer to be about such a dangerous and endangering stereotype of self as ‘the homosexual’. Only the latter is on the side of suicide – the former is about creative relief from norms that fail to either offer mimesis or vital internally conflictual art forms.

All the best

Steve

[1] Martin, S. (2017a) ‘Introduction’ in Martin, S. & Spalding, F. (Eds.) John Minton: A Centenary Chichester, Pallant House Gallery, 7-9.

[2] Martin, S. (2017b) ‘An Expression of Self: Minton’s Self-Portraits and Objects of Desire’’ in Martin, S. & Spalding, F. (Eds.) John Minton: A Centenary Chichester, Pallant House Gallery, 69-88.

[3] Martin, S. [Ed.] (2011)) Edward Burra Farnham, Lund Humphries, 69-88.

A queer approach to: 7. Curating the Male Nude

Sunday, 23 Sep 2018, 17:36

Visible to anyone in the world

Edited by Steve Bamlett, Sunday, 23 Sep 2018, 20:25

A queer approach to sexual preference labelling in art-history: looking at case studies in British mid-twentieth century art: 7. Curating the Male Nude

The aim of this group of blogs is to look critically at some of the publications relating to gay male artists in the mid-twentieth century. This is in part to begin trawling for a dissertation topic for my MA in Art History. My initial thoughts relate to focusing on one of these artists, although their contexts include each other, their treatment of male nudes in relation to the iconographic, contextual and stylistic features which propose such a subject for art (for some of the choices this will include photography as well as painting) and ‘queer theory’. This will look at the issue of labelling of course, particularly at the important terminology of ‘homosexuality’, which dominated the period. My hypothesis will probably be that such a term was, and remains, a means of marginalising, even to the point of negation, of such art. This blog looks at some reflections on the curation of male nude art collections / assemblies.

This is timely because of the upcoming Royal Academy exhibition, at which the Guardian critic, Jonathan Jones, smiled, because of its aim ‘for “parity” of naked men and women’, raises the issue of how and why the nude is a hegemonic female or male form across various culture & societies. This question has been asked, hence for my first example of curation is a book (perhaps even the sneered-at form of the coffee-table book) from 1998 by the then ubiquitous, Edward Lucie-Smith, Adam.[1]

Lucie-Smith’s final chapter is about the nudes as ‘The Mirror of Homosexual Desire’ and uses the term ‘homosexual’ in a totally unproblematic way. He is aware of queer theory, in its birth-pangs, but sees it, I think rather problematically and dismissively for all involved as ‘an offshoot of feminism’ (174). But his position is more nuanced than this erroneous reading would suggest. Queer theory is based on a belief that the querying of norms in art – representational or otherwise – creates the kind of crisis in signification, even if momentarily and cumulatively, that produces change from beliefs that have become conventional ‘truths’ in the teeth and frame of those norms. i can empathise with the Lucie-Smith of 1998 because at that time gay male identity needed prideful bolstering in those early days of change in legislation and mores that yet has not come to completion. Yet in 2018 we are much nearer. There is weight in queer theory’s insistence that we spend far too long creating binary distinctions between straight and gay, male and female when the issue for all is the regulation of desire and belief

Lucie-Smith (1998:179) also points out the immaturity of our early positions as gay men who used nude images (sparingly) as an index of a desire that must be legitimated and justified. Of the ‘characteristic art of the rainbow coalition’ (the union of left, feminist and identity politics) he writes:

It does not offer opportunities for the creation of new images of the male figure. Where male imagery is present, as in some of the complex compositions of David Wojnarowicz (1954 – 82), it is employed largely for its shock value, and is usually lifted from another source, such as male pornographic magazines

Although the argument about Wojnarowicz does not hold water held next to that Artist’s achievements in what is quintessentially QUEER ART, his point is sound and made clearer through the chapter. We do not make the male nude usefully into a possession of the gay community. What he (187) sees as more hopeful (and I agree) than that aim is that the: ‘meaning of male imagery seems to be becoming more ambiguous,… the male nude as a subject for art is currently going through one of its periods of radical transition.” This is a description, whether he calls it this or not, of queer theory in praxis, much more so than some of his own appealing photographs (John and Richard 1997) that bothy eroticise and, concomitantly, emotionalise relationships to and between gay male nudes.

Where this book is still valuable is in its perception that male nudity becomes radical when it is contextualised outside the normative – alongside domesticity in Hockney for instance (142), or in relation to the proud nudity of males with a disability (126f) or where gender roles themselves are brought into question, without recourse simply to the substitutive conventions of drag (132f). How much more however is done by two books representing more recent exhibitions in Munich and Mexico City.

These modern exhibitions are represented by two books / catalogues of exhibitions (three if we account for the version of the second one that is written in French and dealing with the exhibition when its focus was much more purely European[2]): for the Leopold Museum in Vienna (2012) & the Museo Nacional de Arte (MUNAL) (2014)[3].

The Munich exhibition probably remains of the exhibition and exhibition-catalogue of most use for me if I go with this subject and I have already used it to talk about male nudes in Ingres and Etty in A843. Its curatorial focus however is strongly on literary-visual-political discourses of masculinity with a stress on essays on sources in metamorphic poetry (17ff), negotiated identity in space (27), sexual semantics (37f.) after Winckelmann (an excellent 2 chapters 57 – 76 being on that influential figure himself). It opens with issues of decency and ends with the sublimations that made the nude the model par excellence of Nazi statehood. This curation has an obvious intent – to cause introspection about the nature of German concern with the politics of the male body.

The French Cogeval exhibition is in part represented again in Mexico City but the contrasts between European and South American iconology of the male nude is something much more than an additive. Here masculinity is looked at in terms of construction of it in worker politics of revolution as well as nationalistic state appropriations of the nude (p. 44f followed by material on ‘the classical ideal nude’ – also appropriated by the European right in the twentieth century). Nevertheless, this is a very rich source for a consideration of the male nude as iconic image of embodied notions – nature (175f), heroism (93f) and ‘truth’ (139ff.) are obvious ones. But what of pain (207ff.) and desire (231ff.). Here other traditions are important – especially in Spain. So I await a visit to the Ribera exhibition this week in Dulwich. But Renaissance forms are also mighty. I’ve begun to reflect on these but the Royal Academy exhibition this year will help further. The Mexican book also includes material that makes me joyous (especially on Ron Mueck).

All the best

Steve

[1] Lucie-Smith, E. (1998) Adam: The Male Figure in Art New York, Rizzoli International Publications Inc.

[2]Cogeval, G. et. al (2013) Masculin / Masculin: L’homme nu dans l’art de 1800 à nos jours Paris, Musée d’Orsay

[3] Natter, G. & Leopold, E. (Eds.) Nude Men: From 1800 to the Present Day Munich, Leopold Museum & Hirmer; AND Arteaga, A., Cogeval, G., Ferlier, O., Mantilla, A. & Rey, X. [trans Dodman, J., Huntington, T., Itzowitch, C. & Penwarden, C.) (2014) The Male Nude: Dimensions of Masculininty from the 19th Century and Beyond Mexico,Museo Nacional de Arte & Paris, Musée d’Orsay.

2 thoughts on “An old blog recollected: A queer approach to sexual preference labelling in art-history”