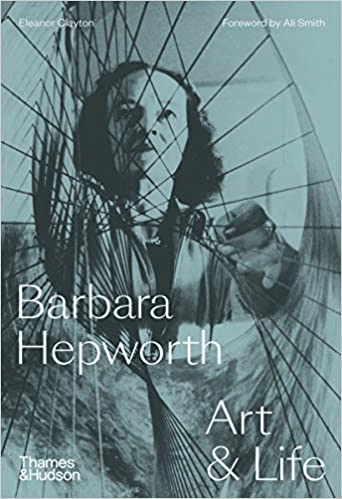

‘I have never understood why the word feminine is considered to be a compliment to one’s sex if one is a woman, but has a derogatory meaning when applied to anything else. …/ There is a whole range of formal perception belonging to feminine experience. So many ideas spring from an inside response to form; …’.[1] ‘You never like arrogant sculptures nor fierce forms – but I do’.[2] [The latter from Hepworth in a letter to her ex-husband, Ben Nicholson 21st January 1969’] Sex and the genderqueer in Barbara Hepworth. Reflecting on the current Hepworth retrospective at The Hepworth Museum Wakefield and a new biography by the Museum’s curator: Eleanor Clayton (Foreword by Ali Smith) ‘Barbara Hepworth: Art & Life’ London & New York, Thames & Hudson.

It is very fitting that this book has a foreword by Ali Smith because no contemporary artist could have so much empathy with the way in which Barbara Hepworth produced from the interactions between her art and her life a distinctive ‘voice’ and made that voice matter politically, culturally and as a commitment to the improvement social, natural and person-made environment. Only Ali Smith, owing nothing to the ‘discipline’ of the history of art but thanks to something that is incidentally a useful tool to lever out otherwise lost knowledge, would be so bold as to praise the way that voice spoke not only about both why her life and her work are ‘one and the same’ dynamic entity but also to note ‘the daftness of ever splitting one from the other’.[3] What is especially important is that, though Hepworth would not have had patience with he term ‘genderqueer’ her talk about the interactions of gender and biological sex in her life, and responses to the appalling things said of her in these terms would demonstrate the need to ‘chaps like us’, as she addressed the political activist an ‘one intimate friend’, Margaret Gardiner, to recognise that they are, ‘a different sort of shape! …’.[4] That shape differs both considered, ‘(p)hysically & mentally’, she goes on to elaborate and includes in the physical not only body shape but how clothes are worn and gender-roles played out. Of course in becoming a ‘chap’, Hepworth is making a joke but it is a joke rooted in physical and mental, but not necessarily sexual orientation since that is not a gender variation, realities for her as a woman.

That is why I extend the citations in my title to a quotation to her ex-husband Ben Nicholson, who, though also predominantly (and perhaps totally) heterosexual in his choices of partner, can be both praised and, a little, disparaged for his ‘feminine’ distaste for large and arrogant monumental forms required by national and international (but also definitively) patriarchal institutions, such as the ‘walk-into’ or ’walk-through’ forms commissioned by the Tate and the Hakone Open-Air Museum in Japan.[5]

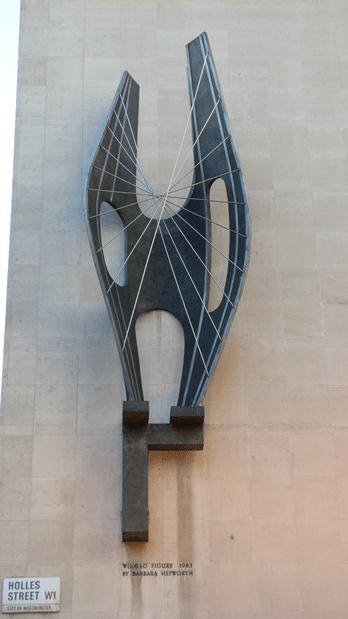

Now I have to say that I somewhat share Ben Nicholson’s ‘fay’ distaste for monumental sculpture of this sort, though I love the Winged Figure II that she provided for Lewis’s Department Store in Oxford Street and would not include this in the same description. Indeed Hepworth herself saw the Lewis commission as a means of using monumental art to share ideals, not socialist but at least co-operative, with an enterprise with rather more social responsibility than is the norm.[6]

But I think it is not an over-reading to see Hepworth’s comment to Ben as part of a dialogue with sex/gender, social roles and gendered linguistic codes that we can see evidence of throughout Clayton’s life – so respectful is it of Hepworth’s own words rather than art-historical summary. That patriarchal attitudes often include a kind of arrogance in men I may have to ask you to take on trust but Hepworth constantly plays gendered games with references to anger and reactive violence that I am sure I do not have to persuade you to be associated with men in the mass, even if not all – perhaps not even most – men. ‘Fierce forms’ might almost be a description of one type of male stereotype, although clearly not applicable to the gentle Ben, no matter how capable he was (as this biography often shows) of ensuring that any housework and child-care tasks not taken care of by Nanny, or ‘Matron’ as she is sometimes called, to whom most middle-class women, even those in ‘genteel poverty’ like Hepworth, could rely upon, fell on Barbara not he.

She criticised the patriarchal leaders that dominated Government before, during and after the Second World War for being likely to be ‘too gentlemanly’, where ‘gentle’ appears to feminise masculine response, to punish fascist leaders in a way that would show capacity to ‘hate evil with passion – sustained, logical & ruthless’, the alternative being ‘suicidal apathy’. This is not just a comment on national mores, it is a casting of self in a superior manhood over those in power.[8] She was constantly herself told by the art press that she looked too feminine to hold a chisel or a trowel and the smooth finish of her ‘ovals’ was sometimes attributed to her sex/gender preferences (unlike the rugged forms of Henry Moore), to say nothing of The Yorkshire Post’s 1937 assessment of the stage reached in her remarkable career: ‘… if no other consideration were relevant, it would still be remarkable that a year’s sculpture of such force and determination could come from a woman’s hands’.[9] Yet under the acknowledged love of ‘curved, open forms’ (as Clayton appropriately describes them) is merely a transformation through rhythm of otherwise violent percussion, or in her words: ‘hundreds of thousands of hammer blows …’.[10]

And in dealing with the Socialist politics needed after the war on fascism too she could openly advocate the language of an extreme masculinism: ‘The difficulty is how & where to act – where is the power & virility? …’.[11] It is clear to Barbara it does not lie in the British ruling class of 1944 though a certain ‘virility’ certainly does become her: ‘we must simply act clearly to save our children having to pay it for us’.[12] And indeed when theorising her art, anything that looked smooth and easy in her work was an appearance to the undiscerning gaze only. For instance she condemned the British Council’s decision to stop her from including graphic work in the Venice Biennale in 1950 that was ‘colourful and dominant’, including some ‘more violent oil ones’, with the intended or unintended effect that ‘they have taken the spice out of the exhibition & the result will be damned ladylike’. As Clayton goes on to observe it is clear that for Hepworth for ‘harmony and balance … to exist and be appreciated they must be accompanied by violence and discord’. [13]

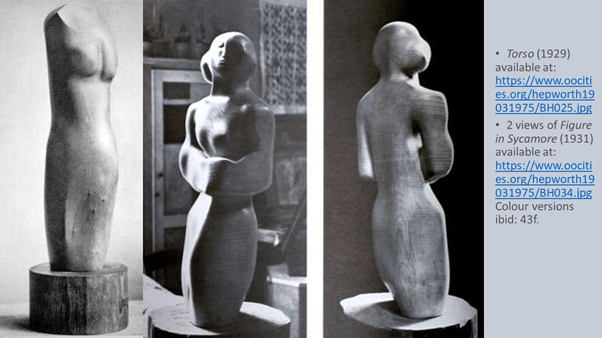

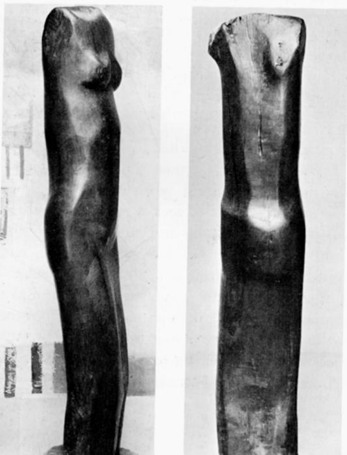

Such formulations in Hepworth’s ways of talking about life, art and the relationship between art and life had a lot to do with a base belief in the necessity in life and each person of degrees of androgyny and androgyny speaks very clearly from her standing figures and forms taken as a whole, which she described as neither ‘abstract’ nor ‘particularised’ but rather ‘generalisation’.[14] To some extent sex/gender qualities become generalised too, although never entirely since it was also important to Hepworth that women assert themselves in societies that diminish the feminine in its entirety. These figures often take a phallic form and such as Torso (1929) and the amazing Figure in a Sycamore (1931) and Torso (1932). It was a joy to see these in the exhibition standing each on its own at distance, as well as near to, although the last one was represented by a Paul Laib photograph from the official records of her work now stored at The Hepworth in Wakefield.

The generalisation reaches further into abstraction (‘more formal all traces of naturalism disappeared’ as she puts it herself), including more obvious sex-markers, by the time of the 1934 work, Standing Figure, which can be seen by zoom imaging in the Sotheby’s sale website (use link).

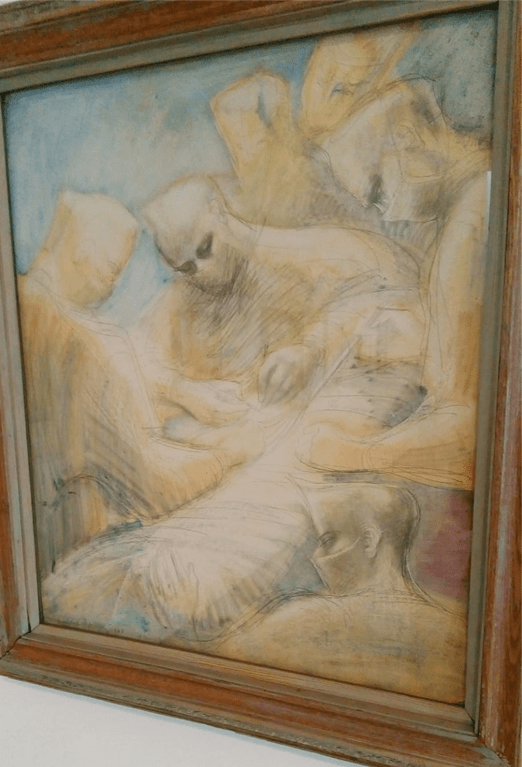

However, these less interesting to me works aside, sex/gender is dissipated most in the concentration in Hepworth on the body as an instrument of work and product of work which summarises the need to use definitively hard materials (even her favoured wood), to emphasise the violence of the handling in the desire to produce that which is soothing and curative in the product. The central idea is the hands, although more truly the ‘hand’ seen as a means of extending the powers of the eye into the realm of the tactile and precise and sometimes violent manipulations. This idea reaches its acme in the surgery drawings, in which the hands of figures seemed to glow across the room at the exhibition, but it is also marked in her awareness of her ‘lack of contact with factory workers’, which she substituted by using her ‘knowledge of the mills in Yorkshire & 18 years of intimacy with all that goes with collieries & mills’, if only in the imagination of a middle-class socialist with very intense political passions.[15] A key painting amongst the surgery painting is simply called The Hands (1948): in it a horizontal line of hands (one female behind a phalanx of male surgeons) prepare themselves to access and manipulate, and, of course, tend to, the body of someone here unseen. But the analogy Hepworth herself pointed out to surgeons she spoke to with the sculptor’s work is clearer in the detail from Reconstruction (1947), though it will be seeable to anyone not only in the originals you see at Wakefield but in reproductions.

A WordPress blog from ‘Morbid Art History’ gives more than enough excellent coverage to deepen the reasons why hands became of such importance to Hepworth. It is called Barbara Hepworth’s Hospital Drawings: Sculptural, Surgical, Tactile, Haptic and can be accessed from the link provided the writers allow this. Otherwise, please search – it is a very worthwhile blog. Before finding it I had intended to explore hands myself. My own suspicion though I will take it no further here, or at least yet, is that it was a common icon in the short-lived Unit One group in that the theme is also very prominent in Edward Burra and I do not believe that this was a product of concern for the disability in his own hands. But at the exhibition itself one image of the surgical team seems to revolved around a focus on the hands of the whole team – men and women – with their hands penetrate in some rhythmic dance inside the hole they have made in their patient that recalls images of sculpture from the exhibition that I want to show later. It is busy, energetic, almost violent in its rhythmic focused caring.

But the chance not to pursue that theme has advantages. Tactile and haptic interactions (download the scientific paper from the link but you may need to register, as did I some time ago) operate sometimes not only in direct touching but in the imagination of such touch that feeds sensation back to the skin. The best experiment indeed to convince yourself of this is this exhibition and it applies to some of the drawings and oils as well as the sculpture, especially the surgical drawings. I think These sensitivities are not constant either across populations or longitudinally in one life. That certainly is my experience but my indirect haptic perception seems stronger now at the age of 67 than it was when I was younger, for whatever reason, and I certainly believe we can block those sensations voluntarily or that they can be blocked involuntarily, but of course, this is hypothetical speculation alone.

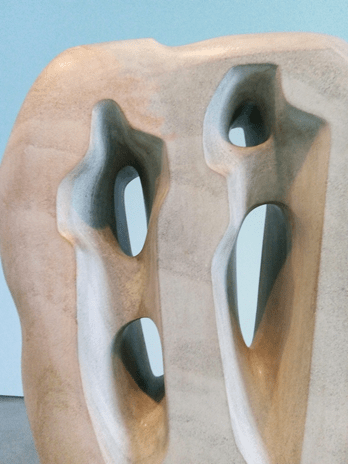

Nevertheless the rest of this blog is an attempt to share haptic perception such that any reader might reflect if they feel sensation at the hand, or imagined at the hand or however you want to put it (or other region domain of the skin) from those examples I discuss. Let’s start with an obvious example of where Hepworth’s art evokes – and she has said it was her intention – a sense of tension in the perceived object where the integrity, ‘wholeness’ and closedness of the art object feels tensile and stretched to bursting or fracture. Sometimes a threat to penetrate or to evoke penetration beneath its surface emerges in some still images. Some holes in objects invite us into a interior otherness and find within other objects (had I time I would investigate the effect of Hepworth’s knowledge of Melanie Klein through Adrian Stokes, her friend and psychodynamic art-critic), others penetrate through in straight or distorted travel paths which open up inner curvatures and colours, others remain impressions of violence or being hollowed out, visible only in some kinds of light like old wounds. Sometimes she made the tension between parts perceptible by the use of tense string pulled across a hole or fracture that makes association with the attempt to both hold a piece integral but also to engage tactilely with instruments of music – perhaps even Orpheus’ lyre as we will see in a later video. I want to start this touch fest by reproducing my first pass across several objects, whose names I did not at this stage record, concentrating on one particular one of those.

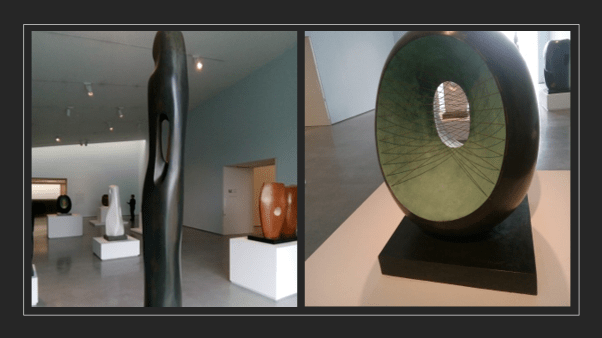

As justification of this method, I told myself that this exhibition was too rich to see in one go and that I needed to return before I particularised my responses, at least in terms of most items like the forms – ones spanning her career – in the first room you encounter. Titles, anyway, in her work, though important, are also often as an afterthought, in which others participated, as her a letter of 1946 just before her Lefevre exhibition in London reveals: ‘I know the feeling & intention of each carving but the exact words are elusive & I’m also very fussy about names & words generally … . I will list you the ones I’m sticking on’.[16] So here goes with images to illustrate the paragraph immediately above this.

These are basic forms of which as Clayton emphasises, from Hepworth’s own words, there are from the outset two basic ones: ‘’the standing form’ and the ‘two forms’, of which a classic example is seen to the right of the first picture, although it is an amalgam of two forms of the third type in this case. The third type is the omnipresent ‘…”closed form”, such as he oval, spherical or pierced form’, of which we see a more basic and ‘unstringed’ form here, but which also plays with notions of wholeness and the partial, form and the unformed or distorted, by some cultural measure, in form.[17]

Tension is not confined to the grouping of two or more forms but is present between binaries and multiple forms within the same form like outside and inside, colours, open and closed surfaces, curves and gradients, lines and filled shapes, and the vital conflict between solid and space interior, wholes and parts, and surfaces and solid depths. In her early work figurative forms are heavily ‘particularised’ to use Hepworth’s own term and she returns this in some later figure drawing, which are a little more generalised but are gendered and in relations of attraction and opposition, either in dance or love relationship.

But the interest in dispositions and shaping of space and solids is the same as in more generalised, and eventually fully abstract forms, which might separately be either standing forms or figures. All the basic Hepworth forms appear together in Hieroglyph in abstract where the stone yields anthropomorphic forms. All ‘sculpture to be good must (in my mind) be anthropomorphic to some extent’ Barbara says, possibly in 1950.[18] But sex/gender is extremely fluid as indeed duality itself as could be seen from the single standing figure in Himalayan rosewood she called Dyad in 1949. The play between monads and dyads becomes an ungendered and perhaps even unsexed statement of simple tension between and within forms that is the very definition of what it is to be human (or perhaps even animal) or anthropomorphic. Hieroglyph (1953) was a play with all the agencies used in Hepworth’s forms and both figurative (in a kind of negative relief form) and abstract, as Clayton says quite brilliantly:

… two distinct figures are articulated by polished piercings made in Ancaster stone. While separate, they are bound within the same organic material, its geological composition visible in the varying layers of colour and pattern. These ephemeral figures made of space metaphorically convey Hepworth’s belief in the strong ties between individuals embedded within the same earthly society.[19]

You can query words here like ‘ephemeral’ because empty space is less ephemeral one might think than even stone but what strikes one is how solid stone conveys both proximity and distance, and, attraction and repulsion between the figures which also articulates itself in the invitation to touch and stroke the relief of curved and flat surfaces which make the viewer and sensor of this piece break its quality as a monad into many multiple forms embedded in each other. This is beyond heteronormative coupledom I think as the best of Hepworth always is, but I think in Henry Moore, this is much less the case. Before I had read about the piece, it was the first form I photographed and I can remember the feeling that to see this piece required moving ever more to some way of contacting it skin to skin, because the texture of the carved stone itself is so organic in its layering, its insides offering varied surfaces both light and dark, smooth and sharp, angled and curved that elicit haptic vision and invite touch itself. Do you feel in this photograph – just taken on my Nokia smartmobile – that the photograph is trying to get ever nearer to the object. To me it demonstrates a kind of desire.

The motifs that continual strike out of Hepworth locate desire not only in groups of, or monadic, figural forms but in the pull and push of an observer’s, especially an observer themselves on the move, changing perspectives, attractions and repulsions included, in landscape. Many figures are neither animal or human – or are both – and in being so also invoke mythical archetypes, especially angels and Madonna-based or simpler mother-child moments of attachment and detachment through growth and decay. Some of the best mother-and-child early pieces (see link for an example) recall Hepworth’s own memories of Yorkshire granite outcrops like Brimham Rocks and the urgent Cow and Calf rocks over Ilkley. In human vision even ‘natural’ stones utilise the spaces in between them to articulate desire, need, contiguity and necessary detachment irrespective of figural titles.

This is true too of monads that turn out to be far from monads based on the angle of seeing and in which not only vision of form but emotional association varies in the short circuiting of the figure, but even more so if we take into account changes of lighting quantity, quality and angle of approach that sculpted forms admit. There is no unitary point of view, no single vanishing point in such experiences, however hard we try to acculturate ine by advising the best way to see a sculpture or by photographing it into stasis. In the first room of the show, I tried moving my point of vision, as I believed the object (whose name I still do not know until my next visit – somehow I am resisting searching the records). Here is an attempt to capture my visions of this piece – less monad than a vision of the many emergent from an obsession with the one, almost the opposite of the kinds of Platonism that appeals to authority figures. As you observe these stills, imagine yourself in various kinds of motion in relation to the object if you can because it is, remarkably, the same object, which can sometimes confront you with rejection, invitation, smooth and very rough textural sensations (without any literal touch moreover) and varying relationships between interiors and exteriors, orifices that are wounds or sexually inviting or both, and a standing figure standing in the variations of dark that reach inside the pierced oval so that what might appear closed suddenly appears dreadfully open.

As I moved through the exhibition I tried to capture circuits around some objects by video and I am hoping they will be mountable in this WordPress blog. The first I tried is the wonderful piece Pelagos (1946) which turned the idea of a Cornish rock and sea landscape as a space in which the roving vision gets caught in the folds of rock or a wave or attempts ‘escape for the eye straight out to the Atlantic’.

Videos are bit-heavy digital forms, but I cannot load them here because my WordPress contract is too lowly to support them. A second one was the even greater later Curved Form (Trevalgan) (1956), which is again based on Cornwall but in some ways recalls an earlier piece based on the Elizabethan processional dance to music called the Pavan (to emphasise the multiplicity of association possible). A third was Orpheus which reproduced the movement of a bird, the tensile propulsions and flows of air between the wings of an angel, Orpheus’s lyre and the vision of his head, as Milton imagines it in Lycidas, flowing in a turbulent river to the shore:

When by the rout that made the hideous roar

His goary visage down the stream was sent,

Down the swift Hebrus to the Lesbian shore. (58–63)

I am more than willing to send these short videos to anyone willing to share a WhatsApp contact, as I have with others.

As you watch these movements (if you ever do) they appear to originate in the object or in the moving space (moving in more than one sense) between viewer (or sensor) and object and continually change the tenor of what is seen and felt. This is a decidedly queer sensation and Hepworth’s work is not only, I’d conclude, genderqueer, whilst mounting an impressive campaign to claim high status for the words woman and feminine, as well as for real breathing women, in our culture, but it can’t be done without threatening both men and women who hold on to gender-normative or the myth of static biological form – for what moves more than biology in the production of endless biomorphs of variability.

Yours Steve

[1] Hepworth (hereafter BH) in 1954 Carvings and Drawings’ Retrospective cited Clayton (2021: 170)

[2] BH in a letter to her ex-husband, Ben Nicholson 21st January 1969 cited ibid: 243

[3] Ali Smith in ibid: 6f.

[4] BH cited respectively in ibid.: 114, 68 (emphasis in text) & 114 – last citation continued.

[5] ibid: 243

[6] See ibid: 215ff.

[7] The plaster maquette of Winged Figure is part of the long-term holdings of the Wakefield Museum so I have seen it many times but it was so much better to see it in such company as provided by this retrospective.

[8] cited ibid: 106

[9] cited ibid: 10f.

[10] ibid: 112

[11] cited ibid: 115

[12] ibid.

[13] cited ibid: 158f.

[14] See BH cited ibid: 42

[15] ibid: 144

[16] Cited ibid: 136.

[17] cited ibid: 8

[18] cited ibid: 154

[19] ibid: 168

5 thoughts on “‘I have never understood why the word feminine is considered to be a compliment to one’s sex if one is a woman, but has a derogatory meaning when applied to anything else’. Sex and the genderqueer in Barbara Hepworth. Reflecting on the current Hepworth retrospective at The Hepworth Museum Wakefield and a new biography by the Museum’s curator: Eleanor Clayton ‘Barbara Hepworth: Art & Life’”