‘I tend not to like conclusions, and have a sense that it is best if the end is left rather open. …/…/ I am not sure this is quite the book I set out to write’. (p. 15) The limits of knowledge and expression as exploted in Martin Kemp’s (2021) ‘Visions of Heaven: Dante and the Art Of Divine Light’ London, Lund Humphries.

Matin Kemp has always puzzled and intrigued me. I started reading him more systematically when I tried to work out why I felt so ambivalent about the history of art as a discipline and yet so attracted by his dry approach to stating what he sees as truths, whether they be popular or not. This partly gets expressed in an earlier ‘review’ blog on a set of essays by this most prominent of art historians who still seems (to use a Kemp word that plays a part in this book too) an ‘outlier’ in the range of the history of art as an academic discipline. That Kemp keeps questioning the kind of book he is presenting to readers and what qualities such books require, such as conclusive arguments as he does in the quotations in my title here is itself unusual and refreshing in the discipline. Kemp sees his difference to others lying in his social origins, his wish to work and live between the disciplines of both the humanities and the sciences, and his passion for straight-forward statement about matters.

He is correct that this book has no conclusion. Rather it is constantly opening up puzzles about what light is and how it can be represented. He is particularly fascinated by attempts to represent, using materials sourced in visibly concrete reality, something other than a physical reality like, for instance, ‘the divine’. Even its framing of the argument is somewhat contentious – taking the idea of the paragone as a competition between different arts ( most often sculpture and painting in the Italian Renaissance) in showing their primacy in the representation of the world or a particular part or aspect of it. He mounts a comparison between how Dante in the Divina Commedia represented in written language the light that suffuses his Paradiso and visual artists. Amongst the latter he includes the mechanically animated presentations used in religious and court masques, which used ways of realising the idea of light, such as numerous lamps, to represent a divine presence in their paintings. He doesn’t limit his examples to illustrators of Dante however – amongst whom Botticelli’s preliminary drawings still rank highest in his view. He uses masterpieces from the traditions of church painting in the Renaissance alongside trompe l’oeil dome and fresco work from the Counter-Reformation Baroque and the machinery and props indicating clouds and lights in religious festival masques. This is a wide range of interest of art (some of which is from traditions never touched by the history of art or kept rigorously separated from each other) hung on the over-generalised idea of the paragone and it does sometimes seem over-stretched. This is more the case when in the last (non-concluding) chapter he compares scientific discourse on light from the Middle Ages and in current science as he knows it.

As a result the book lacks pace and one often feels led from example to example with no idea of why they are discussed in the same long aspiration of breath. The discussion is not all about light so the thematic focus gets lost sometimes. Moreover, in dealing with Dante himself I feel that I never get quite the level of brilliant analysis that emerges in say a wonderful reading of Piero della Francesca’s The Flagellation of Christ.

For instance, his chapter on the poetry (Chapter 2 ‘Dante’s Dazzle’) starts with hyperbole: ‘Paradiso … is the most dazzling evocation of divine light in any artform from any period’.[1] However, analysis of how poetry achieves such effects is short in supply and too often Kemp falls back on statements of the monumentality of Dante’s work, and good descriptions of the ideas it embodies in lieu of such analysis. This can even fall to telling us what the word-count is of a ‘much-respected modern translation’ and various very basic facts about the verse form. Of course there is this: ‘The final vision … is sublimely abstract, ineffable and eternal, ultimately lying beyond the power of words and the compass of Dante’s mind’. [2] But that is all abstract words. Isn’t it?

The recourse to the inadequacy of material words to express that which is beyond words was a common enough medieval rhetorical trope but that is not to say that abstraction can’t be examined and its artistic methods illuminated. This could have been done with the wonderful verse passages from the poem he cites. It could have discussed, for instance, points where representation in words gives way to effects in the sounds, flow or rhythm of the verse. Even its use of analogies of inadequacy or gaps in self-efficacy in other spheres of knowledge could be discussed.

Like a geometer who sets himself

To measure the area of a circle, and, pondering,

Is unable to think of the rule he lacks,

So I was faced with this new vision.[3]

Failure in everything that makes you what you are (a person dedicated to the measurement of space who doesn’t even know which of the available tools he needs to measure a common enough shape before him) is a wonderful simile for the poet lost for words to even begin to match representing his experience. But in the Italian how are the metrics of the verse used here and what is the effect of the caesurae and other aspects of the sound of words. About the ‘art’ of the poet Kemp is as silent as Dante faced by the divine itself.

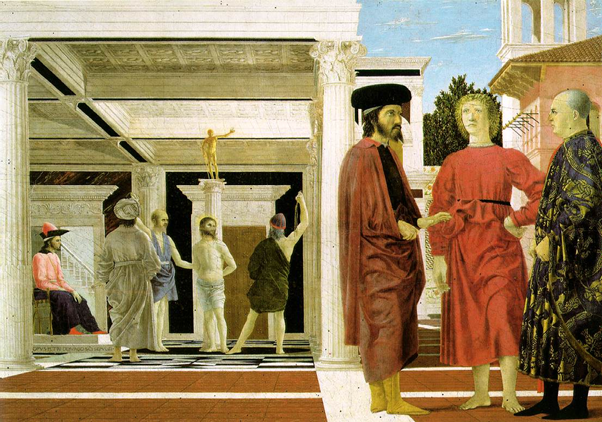

Having quoted all that translated verse, it is insufficient to say that ‘Dante can write of the unseeable’ to contrast writing to art dependent on rendering the seeable by using already visible, and therefore also very tangible, materials for its representation.[4] But this moment does give access to Kemp’s strengths – his long experience of looking at great works of visual art and reflecting on every aspect of that art. Such readings are best represented by his reading of Piero della Francesca’s The Flagellation of Christ, shown below.

In a painting we so often admire for its mathematical precision of perspective, Kemp brilliantly analyses the implications in what we see for reconstructing mentally the conditions and sources of light in this painting, even when that source is deliberately hidden from our viewpoint. We have to ‘work out’ where the extraordinardinary light comes from that bathes only one section of the tiled roof with light and casts appropriate shadows into other sections of the roof. You have to read the explanation carefully and follow it by reference back to the picture and by doing so, your vision of effects achievable in art strengthens. You learn how to read paintings cognitively, of which Kemp is a master, by these means. It does allow Kemp to conclude here (we should note here that he does do ‘conclusions’ at the micro level of painting analyses at least):

The light in Piero’s painting can only signal the presence of God, unseen in person but visible through his acts. Piero is saying that if a light behaves outside natural law, it must be divine.[5]

There is something characteristically pedestrian (‘Piero is saying ….’ feels like prose with no nuance of style at all) in the manner of Kemp’s descriptions of the processes involved in working on a painting’s meanings but WHAT he says is no less keenly illuminating than the prose of a better stylist in writing. Indeed it is more illuminating than many others who write better than he. You do have to work at his prose to follow it – so ‘dry’ is the manner – but what it yields is worthwhile when it comes to visual art. Now I can’t say I felt this about sections on Dante or ‘the physicist Werner Heisenberg’ where intelligence of commentary can be lost in the tedium of the style.[6]

This might have something to do with Kemp’s self-image as being in large part being brought up a scientist but having gone on a different career trajectory, almost by accident. He tells you about this in the ‘Living With Leonardo’ essays. It explains why he uses terms from mathematics, physics and statistics and devotes quite a bit of this book to optics in ways that never feel to be as central or necessary as the author wants them to be. It is also there in choosing to characterise Grunewald as looking like an ‘outlier’ (a term from graphic correlational analysis) when Kemp chooses to discuss him in the company of Fra Angelico, Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo, Bellini, Signorelli and Titian.[7] Of course being an ‘outlier’ is, he says a reflection of Grunewald’s art having ‘wild originality of form and content, and their relatively remote location, even in the 16th century’. The last phrase falls with a kind of bathos as the term ‘outlier’ no longer describes the wild look of the art but the artist’s geographical location in relation to Italy. These are things you can’t help noticing in Kemp.

Having said this I felt the chapter on the Baroque domes and frescos and the use of ‘transgressive illusions’ (here of Bernini) well illustrated by wonderful details of where architectural frameworks are invaded by the life of dynamic, and seemingly alive, painted and modelled figures that you can’t, from distance, tell apart.[8] This is nowhere better illustrated in the book than the analysis of Giovanni Battista Gaulli’s trompe l’oeil effects in The Triumph of the Holy Name of Jesus in Il Gesù’s nave vault in Rome. The description illuminates, if with the usual eccentric value judgements, qualities in the best of Baroque: ‘The inventions and the foreshortenings of the figures are superb’.[9] Reading the last sentence however I still feel I can’t cope with a judgement that treats ‘inventions’ and the technique of ‘foreshortening’ as if they could be judged on the same scale of value. But maybe that’s me.

I enjoyed this book but it is defiantly odd I think.

Yours Steve

[1] Kemp (2021: 31)

[2] ibid: 43

[3] C. Sisson’s translation from Paradiso cited ibid: 43

[4] ibid: 43

[5] ibid: 86

[6] ibid: 214

[7] ibid: 125f.

[8] For Bernini ibid: 162

[9] ibid: 162

4 thoughts on “‘I tend not to like conclusions, and have a sense that it is best if the end is left rather open. …/…/ I am not sure this is quite the book I set out to write’. The limits of knowledge and expression as exploted in Martin Kemp’s (2021) ‘Visions of Heaven: Dante and the Art Of Divine Light’”