‘… the ambiguous sensate body emerges as the primary subject of painting, …. It is intimately connected to that of the beholder, conjoined with our own in a wave or circuit of sensual response’ .[1] An invitation to ‘enjoy immediate access to his fleshy body’:[2] in a bold take on Giorgione’s erotic figures and dislocated landscapes in Tom Nichol’s (2020) Giorgione’s Ambiguity (Renaissance Lives series) London, Reaktion Books Ltd.

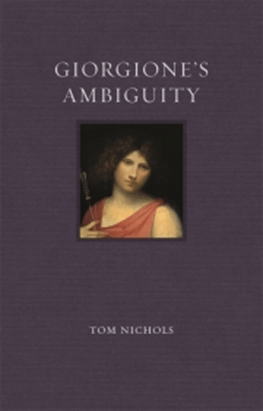

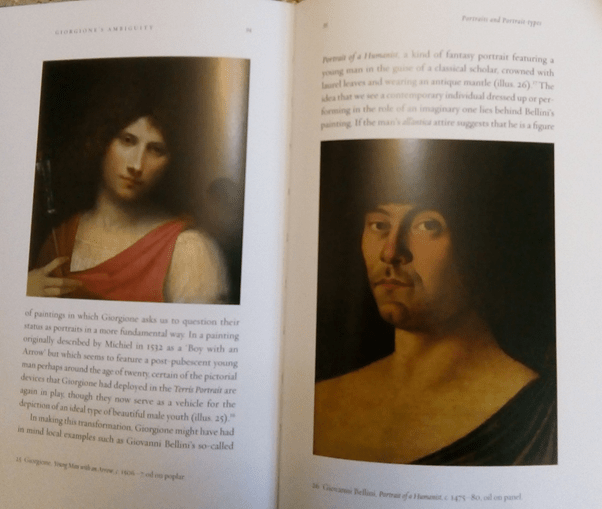

Tom Nichols is an excellent art historian who plays the games of the discipline with skill and knowledge but he is also clearly a writer who likes to cross boundaries. It is the latter quality not the former that makes this such an appealing book, wherein ‘ambiguity’ becomes the means for readers and beholders to become part of the picture in engaging with art. There is something determinedly queer in Nichol’s assertions such as, of the Young Man With an Arrow (c. 1506-7), pictured on the cover, that: ‘Male physical beauty and its power to generate sexual desire is, after all, the obvious subtext of this painting’.[3] There is no prevarication here about to whom such desire might be a legitimate response – there is just response that crosses boundaries of gender, age and other category of person. In the end, desire is not bounded by social definitions of appropriateness and legitimacy – it just is and in our culture this has, for so long, been seen as queer. The same is true of Nichol’s discussion, and surely of the painting itself, of Giorgione’s Venus, even given Titian’s hand in the project.[4] But I can’t really see in Young Man With an Arrow what Nichols claims I see in it. Indeed, compared to Bellini’s Portrait of A Humanist (c. 1475-80), which Nicol sets by the side of it what strikes us is the comparative finessing of our access to the flesh of Giorgione’s young man by the fascination with the undergarment he wears, such that our desire is caught in its mesh of gold and faint colour traces.

Bellini’s humanist male exposes flesh and a fine masculine look that more fully evokes invitation to touch that flesh in my view than does Giorgione, who instead shows us that queer ambiguity in human desire so often gets caught up in the objects that complicate the desire of flesh, even becoming desire’s object in the manner of a fetish. I don’t then fully want to endorse Nichols’ readings of particular paintings – they too often become totally unambiguous, as in this case, rather than showing that ambiguity fails to provide a solid world with which anyone knows how to relate, where the ambiguity of the Young Man’s gender and age is as important as the cusp between clothed and unclothed between which desire hovers in this picture. There is a more honest access to flesh – and male flesh at that, in the Bellini that undermines Nichol’s unambiguous and rather rash treatment of that comparison. In the end it won’t wash to merely equate ambiguity in desire or interpretation with fantasy and Leonardo-like uses of sfumato, the colorito rather than the desegno tradition just because Vasari’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects trained the Western art-world to favour the latter. That is to compromise too much between arguing that art offers itself up to the viewer’s decision-making and the insistence that the discipline of art history understands such statements, which it clearly does not, except in terms that favour expert viewers, or, at least, people who consider themselves expert.

In a sense I want Nichols to go the whole hog and renounce the benefits of the art-history clerisy, though I would mourn his equally wonderful work on Tintoretto, which has the same flair as this book in exposing myths about what constitutes normative perception. This book undermines easy ways of looking that stop short of seeing because of pre-thought responses based on a thin knowledge of iconology or the all’antica tradition or the idea of the single vanishing point as the standard of perspective in landscape settings and the ideal placing of figures in a design. But Nichols isn’t even that ambiguous and steers clear therefore of invoking the queer theory that otherwise is translated here into more conventional terms of a preference for the ‘newly uncertain, unfixed and ambiguous’ in a world no longer authorised by a single creator.[5]

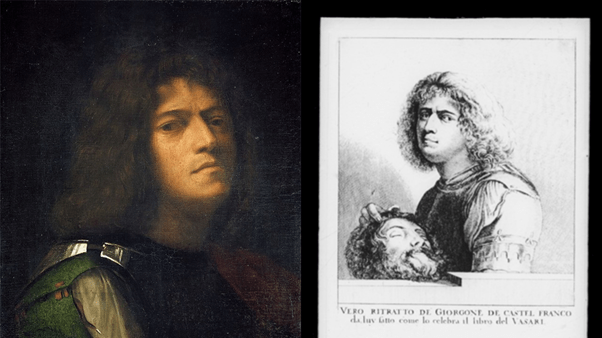

There are reading here however of stunning quality and definitiveness, wherein Giorgione seems captured in all his queer complexity, such as the discussion of the truncated (and the probable reasons for truncation) Self-portrait as David (1503-1504) – given the evidence of Wenceslaus Hollar’s print of the painting of 1650.

It may be, or not, that the ‘right hand (dexter manus)’ in this painting as it was before truncated was meant to show that the painter was being presented as an icon of the dívíno artísta whose works were as inspired by divinity as was the Biblical David. However, what I notice first and foremost are the implication of Giorgione’s fingers in a loving gesture that plays with the locks of the slightly older male’s head. Now Nichol’s deals with this but as a feature of a less emotionally subjective kind that characterises more than one painting:

Delicate fingers and toes nestle among the still-soft hair of the recently murdered victims, who seem, in their turn, and despite their closed eyes, to smile up at those who have recently dismembered them.[6]

There is nothing ‘ambiguous’ about this description of a trait of painting though it does emphasise a queer strangeness that almost gas a Gothic edge. However, the difference and perhaps even the similarity between ‘knowing intimacy’ and ‘moral opposition’ that the painting may hover over here as Nichol’s description advances is both ambiguous and important as marking a painting that goes beyond simple renderings of cultural icons and queers all normative expectations.

There is a better moment of comparison of portraits of young men by Bellini and Giorgione in a comparison of the latter’s Portrait of a Young Man (c.1500-1501) and the former’s Portrait of a Man (c.1485-7), where Nicols recognises that sometimes clothed forms both invite desire and deflect it onto the detail of ties and folds of clothing, so that the object of desire is defused between object and subject and meaning or simple representational function is truly deferred.

I could wish the writing emphasised less of the appearance in these young men, as it does with Venus in fact, of a come-on and more of the sheer loss of selves in objects like clothing – the feel of fabric, the acts of untying and unbounding they predicate and hold off and the imagined touch of fingers evoked by the internalised proprioception transferred between painting to viewer of what it is like to stroke an uneven surface, unaware of the hard edges that will shortly surprise those fingers and disrupt the senses. This is true uncertainty and it is more than about the difference between desegno and colorito conceptions of art, Venetian and central Italian artists or anything suggested by Vasari but is about attempts by art to become performative to other senses, including those Renaissance NeoPlatonists considered ‘…”lower” senses’ than sight alone, as Nichols so perceptively says.[7]

On landscape and figure combinations, Nichols is fascinating but the thesis of what is meant by ambiguity somewhat strains. David Hockney’s take on this is better in that the latter constantly shows us that it is the attempt of art history (even in the humble form of intellectual painters like Vasari) to control the choice of painters to show non-photographic (or non-camera-obscura) perspectives that makes both Tintoretto and Giorgione look odd to us. In fact both rejoice in freedoms that art might take with certainty and the tyranny of the univocal in culture after the Renaissance. His analysis of The Three Philosophers (c.1507-8) however is again worth buying the book for. The language of post-structuralism (italicised by me in the quotation) works overtime here but the overall thesis is brilliantly illustrated from the painting itself rather than being entirely dependent on such abstractions as appear in the following:

The strange assemblage of obscure and contradictory visual motifs generates an effect of bricolage, undermining the idea that we view a joined-up landscape whose combined features will help to elucidate the underlying meaning of the painting.[8]

The prefiguration of Caravaggio in Giorgione of the love of obscure space shows us how radical the former painter would appear if properly seen and not explained away by his early death and limited output. That almost the opposite was once the image of Giorgione, in his valorisation by the Victorians for instance, was, Nichols says, an effect of over-attribution of more conventional works to him. That is worth knowing. You feel you can look at him again with fresh eyes.

It’s a lovely book. Reaktion books are always anyway a pull for me. They seem to liberate creative thought that so many lightly converted Ph.D projects disguised as books from other publishers regularly suppress.

Love Steve

[1] Nichols (2020: 210)

[2] ibid: 97

[3] ibid

[4] ibid: 180ff.

[5] ibid: 212

[6] ibid: 42

[7] ibid: 210

[8] ibid: 138