‘For if we look on the nature of elemental and mixed things, we know they cannot suffer any change of one kind or quality into another without the struggle of contrarieties’ [1] Understanding the life of John Milton (up to 1642) through the lens of Nicholas McDowell’s (2021) Poet of Revolution Princeton, NJ & Oxford, Princeton University Press.

This is a revised version of a blog I first posted on May 17th. I have revised it because on reflection it failed to say why I consider this biography to be so important. I think this is because so many reviews of the book I read – all were good – concentrated on the author’s own characterisation of his work as a biography mainly concerned with Milton’s ‘intellectual development’. As a work on this, including its manifestation in both religion and politics, Milton is impressive but this isn’t what, for me, makes this biography special. So, when appropriate this version repeats the things that I think make this a great book about his thinking in the religio-political word (it is hard to tear these apart in the seventeenth century, and perhaps in English Renaissance in particular). But I add to it material that I think, related to Milton’s intellectual development but in the cognitive domain of ideas about how poetry and poets are conceived and their social, political and ethical role that McDowell offers. This material feels to me a significant and yet well-grounded interpretation that has made me feel that I can now understand his role in the canon of Renaissance writers much better. Suddenly Milton no longer seems an exception in Renaissance poetry but a significantly innovative re-interpretation and re-channelling of its traditions that became lost with the Restoration of the Stuarts. However, I confine these speculative issues to the early parts of this revision.

It is part of McDowell’s closely argued and detailed case that Milton wished, even throughout a period of his life up to 1642 in which he wrote (comparatively) very little poetry in English, that we should see him as the self-conscious apprentice to an international tradition of epic poetry descended from European antiquity. Of course, in Milton’s case, that tradition reserves a large place for a life-in-writing planned in a similar model by Edmund Spenser and the commitment to the widest of most humanly comprehensive preparatory learning. Frank Kermode in the 1970s re-established the political and ideological importance of the tradition of the epic for English history. Moreover, in the course I attended at UCL in the 1970s under his direction, the manner in which Spenser as an epic poet built his life trajectory around that of Vergil was the rationale of the course that emphasised that very fact, including the link to Milton who like Spenser started his career in writing pastoral poetry. Milton referred to him as ‘our sage and serious Poet Spencer (sic.), whom I dare to think a better teacher than Scotus or Aquinas., not least because he linked the epic to Protestant (or at the very least for Spenser the Elizabethan via media which was nevertheless vehemently anti-Roman-Catholic) themes.[2] These connections are constantly reinforced by McDowell: for instance in discussing the relationship of Lycidas to The Shepherdes (sic.) Calendar and of both as precursors to each poet’s great epics as Virgil’s Georgics was to The Iliad.[3]

But, although none of this was new to me – it was established as a model in Kermode’s Renaissance literature syllabus at University College London where I was a learner, no-one ever explained to me the oddness one feels in seeing Milton as a Renaissance poet, even if we accept that some ‘solve’ the problem by calling him a Baroque poet. But McDowell does solve this problem by posing the possibility that a Virgilian life-career, for the purposes of characterising Milton at least, could be seen as distinct from an Ovidian life career which he, citing Patrick Cheney’s work as a source, roots in the work of Christopher Marlowe.[4] I was charmed by the idea that some of Milton’s verse could be seen as containing (in the representation of Comus in the Masque, and Eve in Paradise Lost) ‘ironic echoes’ of Marlowe’s Hero in Hero and Leander.[5] Left like that, the argument would be almost trivial but seen in the context of the Cavalier tradition that would inherit Marlowe’s wit if not his skill the equation of the poetic enemies with those whose life was dedicated to everything that was Ovidian, libertinism in sexual conduct and shape-shifting through role-play and counter to the model of Virgil. But we need to see McDowell’s next volume to see if this argument will be followed through with the necessary conviction. Nevertheless, it places Milton more surely in the Renaissance tradition to understand that John Donne can easily be seen to be the true father of that tradition, uniting a highly sexed poetry based on the Amores and a former Catholic become an Anti-Catholic Anglicanism beloved of James Stuart and chosen to preach before Charles I.

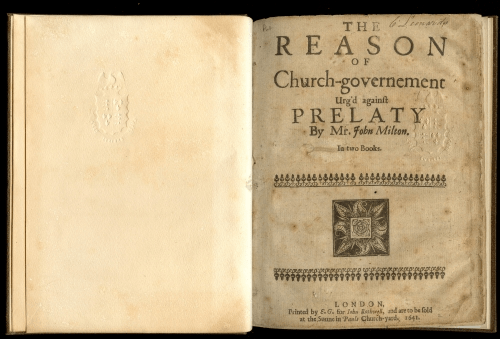

That being still the case it may come as a surprise to those who come to this book for insight into the poetry that this life takes Milton only up to a place where his output of poetry was relatively thin and definitively in a minor key, though of course Comus and Lycidas are precious, if tiny, treasure-chests. Moreover up to the point where this ‘life’ leaves off, with a muted promise of a future volume, Milton is a poet of major proportions only in his own prose protestations, in a volume written early in 1642 that is ostensibly about the governance and ideal structure of a National Church, The Reason of Good Church Government . Or as McDowell says: ‘In 1642 Milton remained relatively unknown’.[6]

But no-one I think could fault the way in which McDowell establishes the significance of this independent thinker, marinated in a culture of ‘contrarieties’, in a time where revolution was as yet not inevitable nor Milton’s career in prose disputation on behalf of, but also attempting to shape the nature of, the English Republic not yet established. He does so by carefully showing that Milton always had in mind a purpose for the learning he spent so much time acquiring that went beyond mere ambition and reached out to significance as an expert in the meaning of creative human love and relationships, even if not as one of its most successful practitioners. And if Milton was by 1642 still more known in prose (and that not much since only one publication thus far had not been anonymised) I think we lose out in the twenty-first century because the kind of prose written by Milton, so much more akin to the rhythmic rise and fall of verse, and particularly the Miltonic (or periodic) sentence has been relegated to the status of bad writing rather than elevated as an example of art.

One such sentence is cited from Areopagitica from 1644, which further developed the ideas in the 1642 book, but this time not urged ‘against prelacy’ only. In itself it presents a defence of ‘varieties’ and ‘dissimilitudes’ (or in my preferred term ‘diversities’), even if tempered by what is ‘moderat’ (sic.), what is ‘brotherly’ and ‘not vastly disproportionall’ (sic.). However the generality of the case argued allows it a reflexive aspect, describing its own structure as a sentence I think – not least in the work done by the word ‘artfully’.

And when every stone is laid artfully together, it cannot be united into a continuity, it can but be contiguous in this world; neither can every peece (sic.) of the building be of one form; nay rather the perfection consists in this, that out of many moderat varieties and brotherly dissimilitudes that are not vastly disproportionall arises the goodly and the graceful symmetry that commends the whole pile and structure.

This 70 word sentence is a pile of pieces (or more accurately ‘clauses’) ‘laid artfully together’ that conduct a debate full of turns of function around its caesurae. These turns vary its rhythm, sense and tone such that contiguous but contesting clauses build a structure that works to both make a point and illustrate it. That point is that just as there is not just ‘one form’ of thought (or church governance come to that) that makes for what is ‘goodly and graceful’ but many such forms that are all absolutely necessary id the whole is not to remain entirely partial (and a source then of disorder) in its nature. That is why ‘brotherly’ matters here – love transcends differences in men, although, as usual, Milton fails to confront his inability to understand like Adam, to whom this must be explained by Gabriel, ‘with contracted brow’ in Book VIII of Paradise Lost the inferior status of women, however lovely: ‘The more she will acknowledge thee her head’.[7] The final phrase then of the long sentence McDowell cites from Areopagitica is the phrase that sums up and self-commends the sentence structure that it helps to consummate so artfully – it commends its own art. Other writers in the history of very different kinds in the art of prose were to do much the same with these kinds of sentence or units of complex meaning building including Samuel Johnson, Henry James and Ali Smith; just to mention my own favourites.

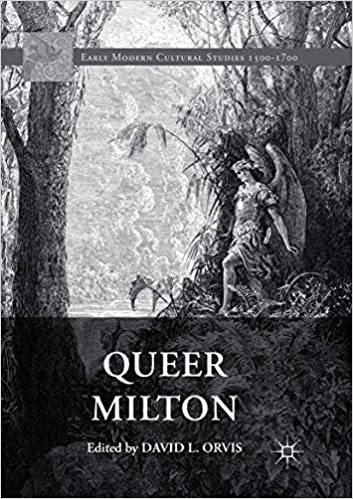

McDowell does not write like his hero but he does write with clarity and precision. With that he clearly reads Milton’s verse and prose in ways that are sensitive to meaning and the ways in which Renaissance poets, according to Stephen Greenblatt who doesn’t get mentioned by McDowell, ‘self-fashioned’ their identity. In Milton’s (and Spenser’s) case this self-fashioning carefully matched culturally inherited conceptions of their role as poets. And this is the key, McDowell believes to the hard-to-explain and certainly strange, in modern critical parlance ‘queer’, opacity of some of Milton’s behaviour and beliefs. About this theme, as we shall see, McDowell retains a politic silence but it jumps out at me from behind his reticence and clear knowledge of Platonism and Neo-Platonism in the Renaissance. Yet Milton studies have clearly taken a decidedly ‘queer turn’ since I studied Milton at UCL in 1973.

McDowell continually makes the point that Milton cannot be reduced to one or other of a binary choice of options when his career, or his politics or indeed his self-presentation as a person is discussed yet avoids the debates about the non-heteronormative queerness of parts of Milton’s sexual nature. Of course, a lot of material in biographical works remains opaque when the writer wants to focus on one important and neglected feature of that life – especially when it sets out to prioritise a person’s ‘intellectual development’ mainly – just as the truths of every life have a kind of opaqueness when written evidence can be read in many different ways. In the example we will go on to look at I see as some exasperation with the ‘queer turn’ in literary criticism on Milton in McDowell but it is never more than a hint.[8] Moreover, the handling of debate on Milton’s life outside of the intellect has a kind of openness to other approaches despite its strong conclusions. As I have said, the chief of these is the importance to Milton of using all the contingent things in his life as a means mainly to map out his route to epic poethood in the manner of Vergil.

One instance of this that I keep thinking about, even after I read the book, is McDowell’s discussion of how and why Milton colluded with the nickname given to him by his peers at Cambridge as ‘The Lady Of Christ’s College’. McDowell even asserts that this nickname became ‘an aspect of Milton’s self-fashioning’.[9] Such a label is anyway a ripe foretelling of Milton’s encapsulation of his own belief in the importance of sexual chastity in the character of ‘The Lady’ in Comus. Except of course, the Lady is led off to dance with the swains at the end of Comus by a ‘faithful guide’, who more truly represents Milton – the ‘Attendant Spirit’ – and is a poet through and through.

McDowell deals with the issue of Milton’s college nickname in Chapter 6, in a section entitled ‘Domina’. [10] In this section we hear of Milton relishing the fact that, though ‘some of late have called me “The Lady” (domina)’ he was now playing the role in the College ‘salting’ of ‘Father’, in which role he was to give an oration. McDowell continues:

Whether or not the nick-name of ‘the Lady’ initially came about because “his complexion [was] exceeding faire”, as reported by John Aubrey, or because of his perceived effeminacy, as many commentators have preferred to assume, one reason why Milton may have been happy enough to appropriate the label was its associations with the greatest poet of Latin antiquity. According to Aelius Donatus’s fourth-century life of Virgil, familiar to early modern schoolboys as it was commonly prefixed to editions of the poet, the young Virgil’s exemplary moral conduct led to him being called Parthenias, ‘maidenish’ or virginal. Milton goes on to suggest that he has attracted the epithet of ‘the Lady’ because “I never showed my virility in the way these brothellers do” – presumably at this point he gestured, with more or less seriousness, depending on how he regarded some of his peers, to a particular section of the audience.[11]

It’s difficult to miss the sneer in the note that other critics ‘have preferred to assume’ the meaning of femininity in way Milton was perceived. It is a sign of what Drew Daniel in 2018 called a ‘clash of civilizations’ between Milton Studies and Queer Studies.[12] It is less obvious than C.S. Lewis’s insistence that Milton’s description of the sexual congress of angels (in Book VIII of Paradise Lost)[13] should be dismissed as ‘filthy’ and ‘foolish’ rather than let them suggest a ‘life of homosexual promiscuity’.[14]But as well as being less homophobic than Lewis, McDowell is also genially open to queer readings though he doesn’t prefer them. Had he discussed, for instance, as Daniel does the various ways in which Milton himself, in common with the period in which he lived, used the slur of ‘effeminacy’ in characterising Adam’s and Samson’s uxorious weakness in Paradise Lost and Samson Agonistes respectively, whilst implying that men can become ‘womanly’ in different ways, he might have convinced us more particularly since the Oxford English Dictionary, as cited by Daniel, says ‘Univocal instances’ (of the meaning of effeminacy) ‘are rare’.[15] This is particularly so since McDowell also does not tease out the associations to Greek Athena that are implied in Parthenias for both Virgil and Milton, wherein both Power, Culture and Knowledge are encapsulated in this most ‘masculine’ of warrior goddesses.

In the end McDowell has, or at least should have, no argument with queer studies which I suspect he does not read – just as he says some Milton critics don’t properly read Milton’s prose. Thus, for instance, was he aware of Melissa Sanchez’s brilliant reading, from the Queer Milton volume, of Comus, he would have seen that her reading merely complements his since both concern themselves with the notion, especially as voiced in Italian NeoPlatonism, of what constitutes a meaningful life outside of merely reproductive sexuality, including the lives of epic poets which are best lived as chaste lives. In the end, the ‘clash of civilizations’ between queer and Milton studies is based on misunderstanding and I think McDowell could not but agree with every word spoken by Sanchez in these sentences, since he too proposes that Milton uses chastity not just as an aspect of his eccentric soteriology but also as charting out a prospectus for an extraordinary life-choice, that of the Virgilian and Spenserian poet of the intellect:

I am not suggesting that Milton himself endorsed expressions of desire that we would now call “queer.” Quite the opposite: I have no doubt that he would side with the Spirit and the Lady. But A Mask also acknowledges that chaste deferral may be no more rational than promiscuous indulgence ….[16]

What most pleases in McDowell is his absolute belief in the cogency of Milton’s decision-making as he plotted his career through a terrain he could not know that it would be as he was. It seems totally correct to me that it is a mere game that say that Milton was consistently a revolutionary in his politics and religion, especially when his object could have been unobtainable without aristocratic patronage had the Stuart dynasty been as long-lived as it thought it deserved to be. It is still a game to posit that he was consistently a Presbyterian until he realised that Presbyterian critics would stereotype him as a sexual profligate following his defence of divorce, and, of course, his own divorce from his first wife. It is just as much a nonsense to say that he was a consistent follower of Archbishop Laud in his beliefs about religious forms and governance in the English church. The way McDowell explains the nuances of Milton’s intellectual and pragmatic self-positioning during a period of great danger is masterly. When power rested with people who enforced your public support for their beliefs in the institutions they represented, such as the patronage system in the support of both religion and the arts, then nuance was the only way and consistency the policy of those who prefer the grave to an examined Socratic life, as Milton definitely did not. It is not just that Milton valued his life – he also valued the future that he believed was to be his and which he brought about.

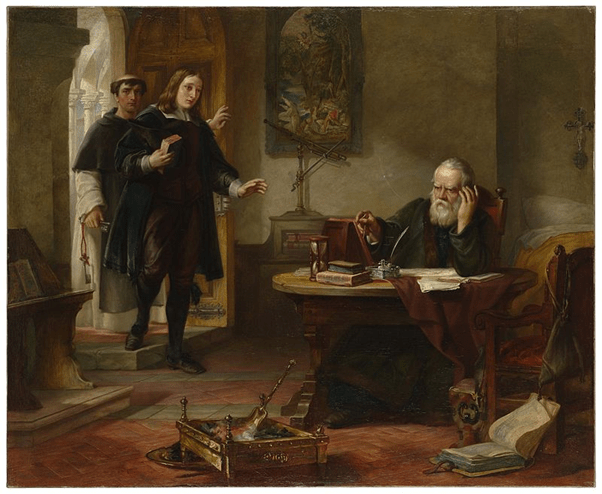

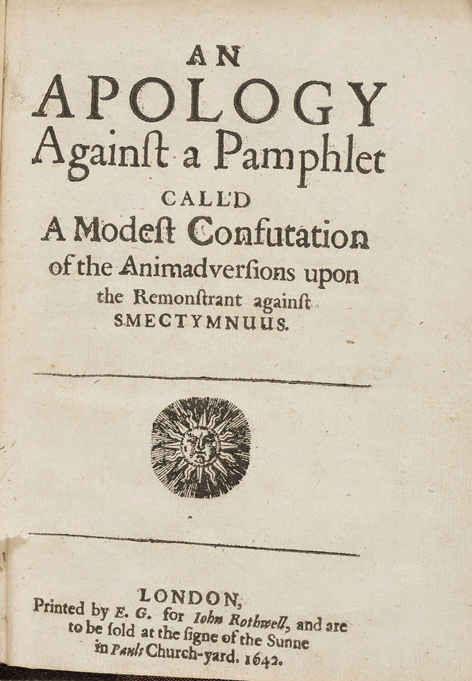

No-one could be clearer about all of this complexity than McDowell – even how his thoughts might have changed privately, though he must follow a slightly different public line temporarily, on a visit to Galileo in Italy where he learned of how Counter-Reformation censorship had brought about the decline of the once great Italian states who vied for hegemony in Italy. Likewise Calvinism could present Milton with a temporary ‘suite of armour’.[17] What really impresses is that McDowell stands up for Milton’s prose as of equal power to the magnificent verse. The key idea is that of the Orphic poet deduced from the traditions of NeoPlatonism, and linked to that a belief in the role of the daemon in Greek and Roman thinking as something more than just a metaphor for poetic genius or attendant spirit. We understand here why Milton did not write an epic based on King Arthur but rather on a world in which his own supernatural daemons that motivated art could live in concert with angels, fallen or otherwise, and different forms of incarnation of the self, such as that of Satan in the serpent – not all of them beneficent. McDowell has not convinced me that I need to read Milton’s early devotional verse again but he does make me want to read (either again or for the first time) the great, and even the less great, prose works. Some passages are more than sublime that I find here in works I haven’t read such as An Apology against a Pamphlet related to the SMECTYMNUUS debates.[18]

I can’t recommend McDowell’s book highly enough whether you are currently a Milton fan or not or interested in Civil War politics.

Love

Steve

[1] from John Milton’s The Reason of Good Church Government, 29 cited McDowell (2020: 389)

[2] Milton’s Areopagitica cited ibid: 236

[3] ibid: 331, & 351 respectively.

[4] ibid: 302f.

[5] ibid: 304

[6] McDowell (2020: 415)

[7] Milton, Paradis Lost, VIII, l. 560 & 574f. respectively

[8] For which see, as an example and the first is a critique of over literal ‘queer’ reading: Adam J. Wagner (2015) ‘A Queer Poet in a Queer Time: John Milton and Homosexuality’ in DigitalCommons@Cedarville (April 1, 2015) available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1263&context=research_scholarship_symposium. But mainly because it introduces a range of the scholars: Orvis, D.L. (Ed.) (2018) Queer Milton (Early Modern Cultural Studies 1500–1700) [Cham, Switzerland] : Palgrave Macmillan

[9] ibid: 158. This is where I might have expected a reference to the theoretical work of Stephen Greenblatt. Perhaps that work is know ‘universally acknowledged’ as a truth. If so that is a dangerous precedent in literary theory.

[10] ibid: 156 – 8

[11] ibid: 158.

[12] D. Daniel (2018: 69) ‘Dagon as Queer Assemblage: Effeminacy and Terror in Samson Agonistes’, in Orvis, op.cit. but also available as a free download at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/268672135.pdf

[13] Bear with me then, if lawful what I ask; / Love not the Heav’nly Spirits, and how their love / Express they, by looks only, or do they mix / Irradiance, virtual or immediate touch? / To whom the angel with a smile that glowed / Celestial rosy red, love’s proper hue, / Answered. Let it suffice thee that thou know’st / Us happy, and without love no happiness. / Whatever pure thou in the body enjoy’st / (And pure thou wert created) we enjoy / In eminence, and obstacles find none / Of membrane, joint, or limb, exclusive bars; / Easier than air with air, if Spirits embrace, / Total they mix, union of pure with pure / Desiring; nor restrained, conveyance need / As flesh to mix with flesh, or soul with soul. Paradise Lost Book VIII lls. 614 – 629

[14] C.S. Lewis’ (1961) Preface to Paradise Lost cited ibid: 70. This also cites Lewis’ preferred naming of angelic sexuality as ‘something that might be called trans-sexuality’ without any hint of just how controversial that choice would appear in 2021, where feminist criticism is engages in ‘trans’ wars of a different kind.

[15] cited ibid: 64

[16] M.E. Sanchez (2018: 47f.) ‘”What Hath Night To Do with Sleep?”: Biopolitics in Milton’s Mask’, in Orvis, op.cit. but also available as a free download at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/emc/vol10/iss1/4

[17] McDowell, op.cit.: 389ff.

[18] Read the luscious passage in ibid: 403.

2 thoughts on “REVISED VERSION:‘For if we look on the nature of elemental and mixed things, we know they cannot suffer any change of one kind or quality into another without the struggle of contrarieties’. Understanding the life of John Milton (up to 1642) through the lens of Nicholas McDowell’s (2021) ‘Poet of Revolution’”