‘It is a breath-turn, a caesura. / … / And I think you see the diaspora happening and want this staying still and this moment of the turn of the breath’.[1] ‘ “…. The collector ‘stills’ his fate. …” / writes Walter Benjamin’.[2] Stilling the noisy passage of dispersion. Reflecting on Edmund De Waal’s (2021) Letters To Camondo London, Chatto & Windus.

Is it a truism that an insistent noise in our ears were better stilled? And remember that time itself is, but is not always for some people, a noisy process. We sometimes feel it might be preferable if time too were stilled in some cases and for some duration, even without the disadvantage of one’s own death. But, of course, to ‘still’ time is quite another thing than silencing noises that emerge from our experience of time: stopping all motion is always an ambiguous moment where what happens next is not always clear to anyone – hence the sharp intake of breath followed by an exhalation (or ‘turn of the breath’ as De Waal has it) in a caesura in a line of verse. In a caesura in written poetry that is designed to be read aloud both silence and the momentary illusion of motionlessness are involved. See this link for some good examples. De Waal is used to motion – that of the ‘potter’s wheel’ since his primary art is the making of pots. And that tool of mobile creation, the ‘potter’s wheel’. has for a long time been the metaphor of choice for endless creation (in Browning for instance) and associated with Judaism (Again Browning’s Rabbi Ben Ezra).

In the quotation in my title, De Waal is imagined the apparently endless, and certainly speedy, process of creation of the pot and the ongoing dissemination of the art created as an endless round, like his wheel, of pottery: ‘The velocity of things, bundling from place to place, hand to hand, …’. Can this process really ‘just be slowed’?[3] And if it were would the absence of speed and dispersion really be an image of safety or order retained or negentropy. For the condition of endless motion is not just an image of the motion of the world or of the potter’s productivity but of forms collapsing into disorder (entropy), and the best instance of that in this book is the Jewish people in diaspora. Hence, this is how De Waal reads The decision of a great collector of art and artefacts to whom he never sends his impossible letters, and which make up this book, and who has given this collection to France on the condition it is never changed, even temporarily, as a monument to his son, killed fighting wars as a French soldier. It is a hopeless task but De Waal understands why Camondo feels he must do it – as if he could arrest the dispersion of Jewish people by settling them in their current conditions of apparent acceptance by others:

I think you know what dispersion means in your heart. You know the world is entropic.

And I think that you see this diaspora happening and want this staying still and this moment of the turn of the breath.[4]

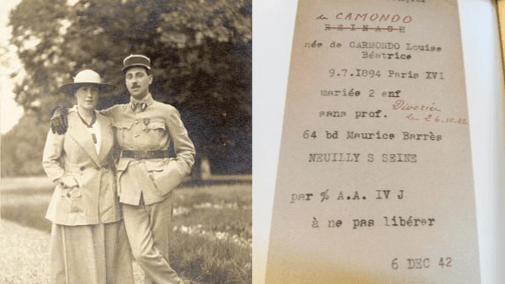

And of course just writing a legal deed of gift of the collection of the Musée Nissim De Camondo with a condition that all things stay the same does not mean they will do – whether those things are the honour of a name, the love of and for a son, the collection of artefacts that honour both, De Waal’s artistic production or the current state of temporary safety of a Jewish family or European Jewry as a whole. This is a painful book because everyone who feels that they are as safe, as Béatrice must have done when her brother Nissim De Camondo so protectively embraced her in the photograph below, can still suffer the same degrading and painful extermination in a concentration camp as other Jewish persons thinking themselves ‘safe’ after Nissim has been memorialised in a static collection of artefacts in the virtual mausoleum that is the Musée Nissim De Camondo. Beatrice could feel ‘safe’ but still be described before her death in the concentration camp to which she was eventually passed ‘hand to hand’, as the wheel turns, as ‘à ne pas libérer’ (‘not to release’ in English).

I sort of wish Ian Thomson writing in the Evening Standard on 20 April 2021 had not noticed that this book so reminds one of Bruce Chatwin’s delicious 1988 book Utz, but he did, and I think he is right. And it too owes a debt to Walter Benjamin and his reflections on the meaning of the behaviour we call ‘collecting’, which is a more possessive, private and psychologically disordered act than publicly curating. I should talk as my collections of books grow daily. Collecting stops nothing but rather just makes the fact of entropy more tangible as a means of reifying delay in one’s response and responsibility for action to make decisions about what really matters.

James Young has written perceptively that the wish to still time is often the task of a memorial but planning, funding and designing a memorial is not he says, from his experience of precisely doing that on a committee commissioned by the German government to build a memorial to the murdered Jews of Europe. Once all the decisions were made on the memorial Young could not say that ‘this might mean the end of Germany’s Holocaust memory-work’. Indeed he argues that conversely it puts ‘the burden of response’ squarely into the laps of ‘living Germans’:

… who will be asked to recall the mass murder of a people once perpetrated in their name, the absolute void this mass destruction has left behind, and their own responsibility for memory itself.[5]

Camondo’s journey from Constantinople to a major centre of Western commerce is a substantial story from history but it is also all the more tragic that its substance is little more than a set of symbols about which there is little to say but that that they have fanned the winds that blow objects from one place to another. Hence my favourite letter is that one where De waal asks, knowing he can get no response, Camondo about ‘the carpet of the winds’in a letter that faces an illustration of a part of it, where one of the four winds blows out a column of air from his mouth from beneath the ornate and heavy pressure of a huge foot of an otherwise unseeable piece of Gilded Baroque wooden furniture.[6] Camondo’s ability to wheel and deal the fortunes of others explains this carpet’s presence, bought as it was from a far greater Jewish emigree of Constantinople who came from the hubris of controlling the winds of commerce to being controlled by them:

It used to be a longer carpet when you first walked on it in the house of the Heimendahl’s …. and when they were in financial troubles you bought it from them.

Yet the winds in the picture still do not seem to know that they are just air on which princes and financiers walk and from which they sometimes come to misadventure. Because this is art and it thinks it lasts forever. It, as both Utz and Camondo may now know, is wrong.

There are crowns and more trumpets and cascades of flowers deliquescing and stiff acanthus framing it all and it is gold and blue; the colour of wind along the wharfs of Galata, out at sea. This is early morning stuff, bracing.[7]

The wharfs of Galata, we need to remember, are a place of commerce where financier dynasties, Jewish and others, like the Camondos had their bracing morning of confidence before settlement under the weight of the European cultural tradition In France and Germany but: ‘People slip into art and are lost’. Indeed, all we have left is that we once lived around the corner from Marcel Proust.

I love hugely elegiac books like this. They tell the captains of our civilized orders not to be so sure of themselves.

Yours Steve

[1] De Waal (2021:117).

[2] Walter Benjamin cited in ibid: 127

[3] ibid: 117

[4] ibid.

[5] James E. Young (2000: 223) At Memory’s Edge: After-Images of the Holocaust in Contemporary Art and Architecture New Haven & London, Yale University Press.

[6] ibid: 10f.

[7] ibid: 10