‘Faced with madness, we bury our heads and willingly pass off the problem to psychiatrists so we do not need to confront the challenge it poses.’[1] Do we as a society need, and can we dare, to acknowledge the needs of those already abandoned at the door of our collective ignorance of their causes and their demands on us all, and act on those needs without passing the buck – or tolerating psychiatry as a convenient whipping-post? Reflecting on Owen Whooley (2019) On The Heels of Ignorance: Psychiatry and the Politics of Not Knowing Chicago & London, The University of Chicago Press. A critical social history of psychiatry in the USA.

Faced with my own experience of a despair that has within its duration felt intolerable but clearly was not at the level of intolerability some people experience, I have realised how lucky I am that I have the social and personal infrastructure, suffused with love in in some areas, that has never abandoned me to psychiatry and has made those complicated feelings, thoughts and bodily sensations tolerable. Having touched its edges I can only put love and attempts of empathy between me and those who have met a limit to the resources available to them that might otherwise have mitigated the onslaught on them too. For many it has meant that they must either accept help fringed with a certain knowledge the socially validated institutions offering it are built upon ignorance of what needs are being here expressed by them. Some of those who have accepted help, and others who have not, have not become survivors and continue to suffer, and often (and that’s the sad part) unnecessarily die. Those people, including many dear friends here and here no longer: they know the lessons of this book but struggle (or plod) on (those who can) to get help in acts of endless and hopeless heroism that is the only way they can get through this thing called life.

If they read this blog (which I don’t necessarily recommend) I hope they can forgive my need to write it to sort out my own ideas. Some of those people are bitter, or sometimes bitter, at their abandonment but more often they are empathetic and forgiving that their losses are so often misunderstood (sometimes even by themselves – but that’s part of the problem). They can see in psychiatry (some of them – perhaps the fortunate ones) what Whooley’s careful narrative supports as a more than likely well-based hypothesis; that psychiatrists and the psychiatric system are made up of:

… individuals struggling to make sense of complex phenomena with imperfect tools, subject to enthusiasms, overexcitement, and dismay, achieving the rare insight but mostly succumbing to confusions, capable of startling acts of kindness and disturbing acts of violence.[2]

We shouldn’t forget the ‘kindness’ when we react to the more disturbing violence or emotionally callous self-interest it can and sometimes does mask. These are the voices on Twitter who counter every critique of their stance with accusation of mental ill-health in their critics. What hope for them?

Working in the system in any role is a confusing thing and I have done this. But it is confusing to work in it because the urge to help is, in the case of everyone I remember, always tinged with deep memories of temporary and unwilling (or so it seems when we must save face with ourselves) collusion with acts that still seem deeply unjust and unfair. Sometimes this was in the interests of colleagues, who were often deeply keen just to see themselves as ‘other’ (and more whole and less ‘damaged’) than the people whose despair they ‘managed’ sometimes so badly lest they too succumb to a lack of sustaining self-belief. Sometimes fighting back has had severe consequences on me and others. Some practitioners had genuinely become hardened to cruelty and no longer even try to justify it as ‘being cruel to be kind’, or invoking their ‘superior’ knowledge of the ‘patient’s best interests’. Some just hold on and survive at cost to their own mental and ethical health.

Those considerations of self aside, this has to be recognised as a stunning book that shows that exposing the poor evidence base of psychiatry or some of the moral dubiety involved is not the answer to the issue of our acceptance of continuing ignorance about the issues relating to mental health that purport to all of its internal and competing schools of thought. That is a kind of scapegoating based on a collective refusal to do anything but ignore the fact that mental distress or breakdown of the mental functions that usually enable life can happen to anyone unless we are lucky. How much easier it is to pretend that it only happens to a group of people other than the collective of which we understand ourselves to be part, whose care and support is the realm of experts in this otherness. This being the case the ignorance that has characterised the complete history of psychiatry through cycles of disappointment, exposure and radical reinvention. It is history that shows that the psychiatric only survives for any length of time when it effectively manages its ignorance by strategies and tactics that Whooley lists in his final Conclusion and all of which are well evidenced from the history that has been told.[3]

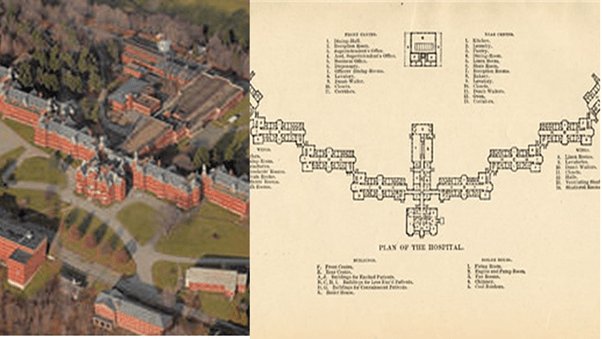

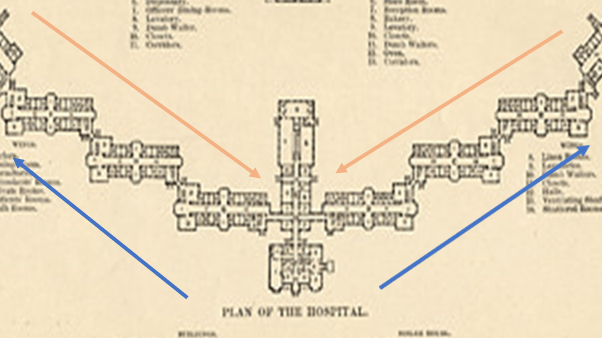

The cycles in psychiatry’s I refer to are dealt with in successive chapters. A summary is useful if you want to know how this book categorises that history because each chapter has strength in conveying exactly the features of this period in which certain forms of psychiatric endeavour become predominant over others. So below I give a brief chapter summary. However in each chapter I have also picked out a point of learning and dealt with separately from the summary. These are points I have been grateful to read and which have each advanced my understanding in respect of this subject. But they mattered to me because they ALSO presented knowledge transferable to other learning contexts, or at least I think so. The classic example of the latter is how learning, for me at least, in Chapter 1 about the architectural and layout of the typical asylum in nineteenth century USA challenges the ubiquity in modern thought of applications of Bentham’s Panopticon model. So here goes:

Below: Table 1: The chapters of On The Heels of Ignorance summarised (selection guide by ibid: 24-26])

| Ch. No. | A reprise of Chapters. Row A (unshaded) = a chapter summary. Row B (shaded) = the point of learning I valued most of all in the chapter. |

| 1 A | This covers the origin of the asylum in the USA, based on the ‘moral treatment’ movement characterised by William Tuke in England and based on a Quaker ethical and religious model, and the European medical asylum model of Phillipe Pinel. The supposed ‘certainties’ (especially about the ‘curability’ of conditions – with claims of 80-90% effectiveness made) that underpin the model and its faith in statistics are described.[4] An early conflict with a specialist medical approach based in neurology is also described. Ends with the ‘crisis’ in which the statistical results of the treatment were found wanting and how this undermined the notion of curability and the credibility of the asylum, under a profession usually identified as superintendents, as a means of achieving that. |

| 1 B | Figure 1 above is based on the fact that Whooley discusses the central importance of the architecture and building layout of the asylum that is considered as ‘not just a building but an instrument of cure’ which extend our understanding of the discourse of the asylum beyond the idea of central surveillance and control emphasised by Bentham’s Panopticon design. The latter has been a really important motif and symbol in modern thought (and art) and so I pricked up my ears. For cure is understood in the model (Whooley treats the Danvers State Insane Asylum in Massachusetts in Figure 1 as typical of the kind) as a function of ‘managerial expertise’ or ‘superintendence’. Much more is mean by this than surveillance from a position of central authority – indeed superintendence in this model exists on a sliding scale. What Whooley shows is that the asylum in the USA was based on an idea that had local as well as general management of a staged process thought to be curative: what he calls, after Thomas Story Kirkbride (1809 – 1883), “a general superintendence of all the departments”.[5] The classification of all inpatients was indeed based on the increased manageability of patients during the curative process – a process involving paternalistic “custodial, disciplinary, educational, and medicative” functions – from a state classified the extreme patients as the most ‘excitable and noisy’ to a cured state of managed passivity and conformity. This treatment is symbolised in the flow of patients between classifications, starting with the extreme locations of the hospital’s east and west wings and ending with rehabilitation for community return in the centre blocks (see Figure 2). The process meant that improvements (shown in the increased apparent self-control of the patients (based on the internalisation of the paternalistic regimens prescribed) were visibly clear to patients as they moved wards towards the centre. Now this image of disciplinary control with its dynamism is clearly something that travelled with the asylum and indeed the idea of treatment regimens imposed from above that is still, in my view at least, part of the medical model. It certainly does not read entirely like a history now entirely dead to us – does it? |

| 2 A | The crisis in Chapter 1 leads to the reinvention of what is clearly now psychiatry under the banner of psychobiology and under the moral leadership of Adolf Meyer (Figure 3 below). The certainties of the last phase were replaced by an admission of an arena about which there was necessary ignorance because of the multiplicity of the causes and plausible treatment options. The ideal was the organisation of chaotic elements into a communicating whole (eclecticism) – the result was disorganisation and internal conflicts that refused to come to terms. The crisis here is that no-one could accept that psychiatric insights into mental illness were really together or individually adding to increased knowledge but rather increased ignorance. |

| 2 B | It is difficult to pin down a means of characterising psychobiology or the various perspective continually tolerated with it by Adolf Meyer (1886 – 1950) but the thing that remains for me is the ever-persistent view, still to be found if not openly preached at the core of mental health teams is his ‘practical, commonsense approach’ that was actually totally antagonistic to theories of the aetiology of mental illness in order to be the more effectively eclectic: “In a field in which nearly every adult has more practical experience with human nature and human functioning than is set forth in most textbooks of psychology, it seemed wisest not to add too much theory, but to make certain that the worker learns to use all the plain facts’[6]. Though this is hardly a world-shattering statement of something central to psychobiology, it felt to me to help explain the persistence in mental health teams – and I am ashamed to say in mental health social work especially – the notion that the only difference that mattered in determining the difference between an effective mental health worker and an ineffective one was that the former was able to sustain a reputation of being in control of their nature and functioning without drawing the attention of anyone who might classify them as mentally ill. Nothing explains better the sense of superiority and the ease of its adoption of a worker over a patient – since the latter’s role is precisely to be the self-fulfilment of the prophesy that not being in a mental hospital was in itself the sign of mental health and superiority of mental nature and functioning. It has justified many an act of disempowerment of service users of mental health services and even cruelty that I observed. |

| 3 A | A significant contender for leadership of the battle against ignorance becomes the Psychoanalytic Movement under Sigmund Freud, although considerably revised into the USA into a form of ‘ego psychology’ and was specialised into the medical model, despite Freud’s support for ‘lay analysis’. It held hegemonic control of psychiatry until the 1970s when the nature of the evidence supporting it and the lack of transparency of the treatments themselves made it seem not a legitimate target for public funds to make it sellable as an effective public health model of mass treatment. Its precepts, which were clearly taking different directions internal to the splintering psychoanalytic movement were deeply critiqued and ridiculed. |

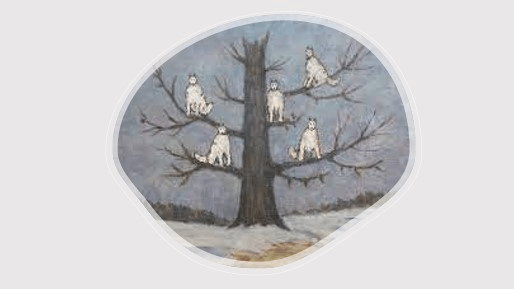

| 3 B | It is commonplace to write dismissively of Freud as a thinker now but that isn’t what Whooley does and I like his style in this respect. Whilst in no way a Freudian he constantly contradistinguishes the way in which psychodynamic approaches were institutionalise not to meet any theoretical view of Freud, or indeed any other psychoanalytic innovator, but the needs of psychiatry to maintain its hegemonic hold over the domain of mental health, including its transformation into a version of the medical model and the hierarchical structure of healing relationships, where power flowed always down to the patient or service-user from a position that could be characterised as undoubtedly ‘superior’. The aim was to foster a group that could control the knowledge set and to mystify it in the interests of power, ‘inaccessible to outsiders’.[7] Now Freud is often accused of this trait, and there is evidence for it, but he also opened himself to learning from his patients, often radically so – as Muriel Gardner shows in her 1972 treatment of his relationship to the Wolf Man.[8] See Figure 4 below for the Wolf-Man’s drawing. |

| 4 A | This has overlap with the time period of Chapter 3 (or at least the 1960s and 70s) but tells of rival ideas about psychiatry that persisted and would eventually help undermine psychoanalysis in the public sphere. The ideas concern an interpretation that saw metal illness as a much wider problem of problematic community experience which needed amelioration at the level of the community and the individual’s group experience – including couples and families but not just that. Whooley argues this diluted the authority of psychiatry and led to rival claims to better address the issues from outside psychiatry and often anti-psychiatry. |

| 4 B | As a former social worker, this section of the history of psychiatry in the USA surprised me since I suppose I really do believe that work with social networks is at the root of mental health work properly conducted. What took the surprise away was Whooley’s judgement that the aim to ‘serve the “mental health needs of the entire population” remained vague’ explained how and why this episode in history wasn’t known to me.[9] Yet it seems correct that this explain some splendid work in politicised psychiatry in the 1960s and 1970s that fed into enlightened reform based on ‘antiwar, civil rights, feminist, and countercultural movements’ (including the fight against heteronormativity) much later in history based on individuals whom I have been able otherwise to contextualise since they were not anti-psychiatry.[10] However, a note on this statement showed that psychiatry could take such a stance based on social intervention and be ready to characterise black and gay rights activists as mentally ill, even in the case of Johnathan Metzl who was capable of inventing the term ‘protest psychosis’ as late as 2010. A similar case on ‘gay rights’ activists could be spoken, by Tom Waidzunas, as late as 2015.[11] |

| 5 A | The dominant mode of psychiatry since and up to the present crisis is described. Based on a return and extension of the ideas of Kraepelin, by people Whooley calls Neo-Kraepelinians, this is a ‘diagnostic (or nosological) psychiatry’ codified by manual, in the USA the manual of choice is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), which takes much greater prominence and importance from the public of its third revision, DSM-III. It introduced says Whooley a ‘paradigm shift’ towards a biomedical model that also appealed to neurology and aimed to be a comprehensive description of the range of mental illness. The latest crisis in psychiatry has attacked those presumptions and were meant to lead to a new paradigm shift which would appear in DSM-5 (having now dropped the Roman numerals for the version) which many in the profession fought successfully to drop. The revisions in DSM-5 demonstrate no paradigm shift. Whooley appears to think psychiatry coasts the crisis this reveals and a considerable dismay in many quarters by using the tactics and strategies detailed above and described on the pages cited for note 3 below. |

| 5 B | I felt rather retrospectively silly reading this because I certainly used DSM-5 while working in mental health without being aware of its problems, other than in the unevidenced support of terms for ‘popular’ (among psychiatrists rather than service users) and highly medicalised messages about the nosology of personality disorders and the inflation of diagnoses of bipolar disorders without any analysis of the social prompts for these kinds of swings, such as those embedded in ‘positive psychology’ for instance. Whooley convinces me now that DSM-5 is actually a symptom of failure to reinvent in favour of obfuscation and an admission of unacknowledged ignorance of any approach but ‘iterative changes’ that merely rearrange the deckchairs on the deck of DSM-III, even whilst the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) sailed away from it – a fact of which to my shame I was not aware: ‘Mere days before DSM-5’s publication, the NIMH announced that it would be moving away from research oriented around DSM categories …[as a] ….”gold standard” …’.[12] This is why Chapter 6 will spend time showing that psychiatry, as I have already cited above, ‘effectively manages its ignorance by strategies and tactics that Whooley lists in his final Conclusion and all of which are well evidenced from the history that has been told’.[13] |

This is a tremendous book. It could further light a fire-keg under psychiatry but that is very much for the profession to decide, because ‘managing ignorance’ tactically is not the compulsory response to the true admission that there is so much we do not know about mental illness. Whooley is correct that we all need to take responsibility rather than blame psychiatrists, who are trying to preserve their job roles just as much as any group has a right to do. Whether it – the psychiatry profession – that is, has a right to do so and save face at the cost of more lives I doubt very much. But I strongly believe that this is the present state of play. But I will hear other voices. I understand the fear of triggering distress in people with mental health concerns, even me, caused by criticism of the only present source of help (or so it can seem) but Whooley has to matter. We need a way forward and a commitment to learning about what is uncomfortable – although I apply this mainly to those who are well-protected from feeling any relationship to mental illth. They are just wrong about that and I pray they do not find out the hard way.

Your ever

Steve

[1] Whooley (2021: 27).

[2] ibid: 27

[3] Whooley (2019: 209 – 213).

[4] ibid: 42

[5] ibid: 41

[6] ibid: 81

[7] ibid: 111

[8] Or at least that is my reading of one of my favourite books in my Freud collection: Muriel Gardner [Ed.] (1972) The Wolf-Man and Sigmund Freud London, The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

[9] Whooley (2019: 143)

[10] ibid: 144.

[11] note 71, ibid: 249 (with information too from the excellent Bibliography of the book)

[12] ibid: 191

[13] ibid: 209 – 213.

One thought on “‘Faced with madness, we bury our heads and willingly pass off the problem to psychiatrists so we do not need to confront the challenge it poses.’ Reflecting on Owen Whooley (2019) ‘On The Heels of Ignorance: Psychiatry and the Politics of Not Knowing’”