‘There is an odd but revealing phrase – ‘in the flesh’ – for seeing art in reality, not reproduction’.[1] What do we ‘pursue’ in the ‘pursuit of objects of art. Reflections on Martin Gayford’s (2019) The Pursuit of Art London, Thames & Hudson.

I admire Martin Gayford quite a lot. However, the brief and rather underwhelming quotation I choose for my title from Chapter 19 of The Pursuit of Art of 2019 ‘Desperately Seeking Lorenzo Lotto’ is not chosen for being particularly typical of this writer’s best or even most characteristic style.[2] It does illustrate though why I admire him whilst not attaching itself to the usual causes of admiration for others who touch on the world of culture, word-pictures, ideas and sensations and the process of making it and its objects accessible and more understandable in your own terms. It has the kind of honesty in front of experience and ways of mediating experience in language that is missed from traditions to which Gayford has relation but to which he definitely does not belong or identify with – at least not consistently, such the academic traditions of the history of art, with their continuing love affair with a dry positivism on the one hand and a socially polished connoisseurship on the other.

Indeed it is this which enables him to have empathic communication with so many different artists and become, for some, a close friend; artists such as David Hockney and Anthony Gormley, who are both mentioned across the essays in this book in this and other regards. But I also choose it because of the prevalence in the history of art as a discipline, especially as a taught discipline, of over-ready uses of assumptions about the ontology of the discipline’s central objects of attention – artworks. Nowhere were these easy assumptions as clear in the assumption that the true object of study in the History of Art was art seen ‘in the flesh’, although it was sometimes my belief that this was a convenient belief when middle-class History of Art students wanted to boast about expensive foreign holidays whilst evaluating them as pilgrimages to the source of the only genuine knowledge to be had of a masterpiece stored in a remote place. Gayford’s use of this fleshes out, so to speak, all the meanings that can be drawn from the phrase and the ambiguity in its common applications to argue their aptness to the works of Lorenzo Lotto. Here is a fuller version of the quotation:

There is an odd but revealing phrase – ‘in the flesh’ – for seeing art in reality, not reproduction. With Lotto and other Venetian painters it’s almost exact: to appreciate them properly you have to stand in front of them. Only then can you sense the carnal reality of the people they depict, the glistening of the skin, gleam in their eyes. the weight of their bodies, the texture of their clothes. These are physical experiences, because paint is a physical substance: a layer of organic and inorganic chemicals that reflect the light, and consequently change every time the light alters. There is no substitute for being there.[3]

Used lazily, as it usually is the meaning of the phrase in the casual discourse of art historians it means exactly and only the meaning given it in the second sentence here – it emphasises that to see the reproduced image of an artwork cannot allow us to claim we know about or even have seen the artwork. As the definitions in the appropriate webpage of vocabulary.com shows, when used thus it works because the term ‘flesh’ is a synecdoche, a form of metonymy wherein a particular part of a person stands for the ‘whole person’ and its meaning can therefore be satisfied when it applies only to the person talking about their experience, when it references oneself not the thing or person seen.

However, extensions of this definition, and indeed most of the concrete examples given in vocabulary.com apply the term to the object or person seen, in which case ‘flesh’ is also a metaphor, which sees an inanimate object, a painted canvas, as if it too were a person. Gayford uses this ambiguity to shift our attention from the person seeing to the notion of a meeting between persons, where both are embodied, which easily shifts to a reference to an application to the body of the figures in the painting. When we see paint in its physical reality, it is a kind of flesh that makes the people themselves in the painting as alive and fleshly as the viewer, a ‘carnal reality’. It is worth lingering here, seeing the term ‘carnal’ though it literally refers only to flesh has the association of something appetitive, that must, in some sense undress the viewer as address the viewed figures. Of course I take this too far but it is exactly how art gains the depth of embodiment – the feel of texture and opaque but soft resistance – that Gayford refers to. However to say that this is the only way of seeing an artwork is clearly wrong.

Moreover, even in this passage, but also elsewhere in other places in the chapter and book, it is clear that just ‘being there’ is not enough to capture such embodied and relative perceptions of the artwork, because after all, the quality of paint is not just to capture the feel of flesh but reflect light which ‘consequently changes’ the image of the artwork seen ‘every time the light alters’. There is a sense, of course that no one visit – or indeed any finite number of visits – would comprehend everything intended by the artwork, even if we confine ourselves to interpretations of its surface appearance alone and not to matters of compositional design.

Gayford is, at this moment talking about a particular painting by Lotto in the museum at Recanati, an Annunciation (see below), which he describes as taking the spectator ‘into a 16th-century room in among the participants in the sacred drama’.

Now, though these features might feasibly be a result of the illusion of a ‘mutual’ awareness being projected by the person seeing ‘in the flesh’ of the ‘flesh’ of both the spectator and the figures in the painting on each side, there is no way in which that feeling isn’t imaginable from even the small reproduction I have given in which the texture of paint has been flattened by photographic reproduction. In my view, we need perceptual precision here to stop the mystification of art objects such as the become a substitute for the religious motifs they often depict. There is no doubt that a reproduction is a different experience from that of the original painting seen in the brief time available to you (hot, sweaty and tired in the midday sun) in a day trip to Recanati.

For Gayford matters to me precisely because he shows us that, in the event, being ‘in the flesh’ in the expected location of an artwork is often a frustrating experience, wherein artworks can be on loan to exhibitions, moved away because of the danger of local seismic activity or difficult to see because, for any number of reasons, the venue housing them is closed, or closing in the time-frame when you are there or just because ‘all flesh’ has to admit it is ‘grass’ and mortal – tired, ill or out of sorts and unable to see without attention at this particular time. Now, I expect the art historians to get the hump here and say but yes, sometimes we see in ideal conditions. Perhaps but those conditions only show you versions of the work that are seeable in such conditions – conditions of light, heat, duration, limitations of space or tolerance when hat space is crowded or any other number of temporal and spatial considerations. The point is that the ‘ideal’ conditions for seeing painting are as ‘constructed’ as any one moment in which the artwork is seen, and that might apply too to its reproductions.

Of course Gayford buys in momentarily to the ‘in the flesh’ illusion but the end of this chapter, and the book, is not just rhetorically effective it tells a truth, and not just about confrontations with works by Lotto, that directly contradicts the assumptions of those who see how we see an artwork as a matter of ontology rather than epistemology based on varied perspectives on the otherwise unseeable work – it only exists in the specific means and conditions of seeing it. It also suggests that knowing a work can never be said to be completed.

… it always looks different when you see it again. So, on another day, and mood, they would all seem changed. You never get to the end of a painter such as Lotto.

The pursuit of art is a journey that never stops; …

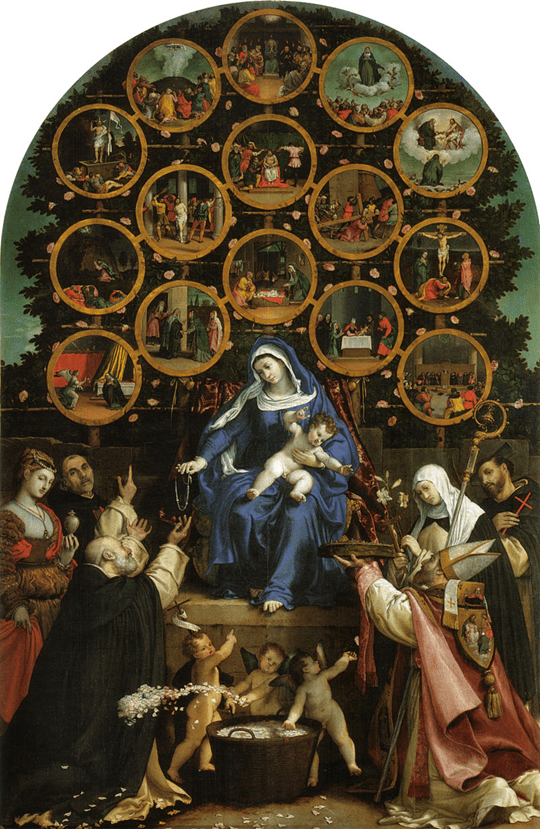

When Gayford in the same chapter tells of visiting Cingoli, a series of contingencies enable he and his wife to see Lotto’s Madonna of the Rosary (1539), which ought to have been inaccessible that day. My love of Gayford’s stories of journeys towards art is explained by the wonderfully light ambiguities in this passage about how we see something ‘miraculous’ in such a picture. That term is used in its contemporary sense here, where it always a conscious exaggeration of a matter of chance, but it captures something that might be a reasonable hypothesis about how and why art is located where it is that might otherwise have gone unnoticed and illuminates the diversities implied when someone tells you that this artwork is ‘religious’. And that it does it in an accessible and irreverent prose is all the fitting for me, where contingency piles up on contingency including people who forget where they put the necessary key to the town hall, a chance expedition of a group of ‘enterprising Americans’ with access to another keyholder otherwise unmentioned:

Under the circumstances, actually seeing it seemed almost miraculous.

….

The Madonna of the Rosary was too idiosyncratically nutty to have gone down well in a cosmopolitan metropolis such as Venice. And indeed Lotto did little business there, which is why he had to be sought out in places such as Cingoli.

Maybe a series of lucky strikes is as near as we might get (or godless me at the least) to the miracles promised in the events we recall in the rosary and which are all illustrated in the preposterous rose-bush that stands behind the Virgin as she hands rosary beads to St. Dominic, an event that was actually meant to have taken place by local legend in 1208.[4] But I shudder to think of the po-faced response to such subjectivity in the MA I endured, where boasting about the places in which you had the resources to facilitate being there ‘in the flesh’ was. And this is a painting (see below) where the joyful largesse of the putti with buckets of rose leaves seems to render especially necessary for modern viewers some way in which the farcical elements of the scene might be seen again as ‘miraculous’. Since the original is ‘thirteen feet high’, we might though struggle for the same awe as Gayford demonstrates in his realisation that the ‘offering of gifts’ is a sacred action. But we can see this in the reproduction – can’t we?

And the same applies to the many well-described journeys in this book and how they illustrate the issues that really illuminate how we educate ourselves about things offered to our senses by whatever good luck we have in the world, even by seeing how and why artists like Rauschenberg might distance themselves from their academically privileged interpreters and who value matters of chance, surprise at finding a new perspective, liking ‘to be the first one to be confused and bewildered by what it was I did’, like having a turtle who greets visitors who ascend to his apartment in the elevator because he (the turtle) senses the chance for adventure.[5]

Sometimes the opportunities art might give you to discover its full potential might be easy to refuse, ‘in the flesh’ at least, such as the ‘dangerous art’ instabilities of Anselm Kiefer’s delight when either his ‘heavenly palaces at La Ribaute’ collapse, as if enacting the falling debris of bombed Dresden or molten lead flows down from an artwork onto its awed viewers.[6] And these delicious essays fall one by one through a reader’s mind with much the same lesson.

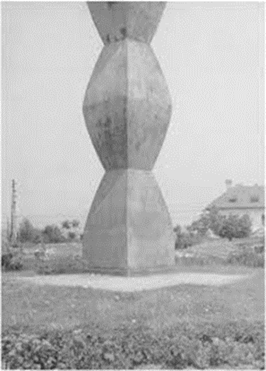

Of course it is good to be there and see an artwork like Brancusi’s 1938 Endless Column ‘in the flesh’ just as it would be to see in the fields it once stood and not in the ‘small park’ that now is all that stands around it in Târgu Jiu in Romania.[7]

Yet there is and has to be substitutes for all experience, since it’s evident, if you have done your homework on Heraclitus, that you cannot step in the same river twice. And when Gayford sends back to London to their friend, Anthony Gormley, his wife, Josephine’s, video of ‘scanning upwards’ the column made on her smart-phone, he still said “Wow!” …[8] And that still is a legitimate reaction to the art itself, reproduction or substitute for that which has ‘no substitute’ though it might be.

So much have I enjoyed these essays, it won’t be long before I blog on the book Gayford and Gormley wrote on sculpture, which I’ve just obtained.

All the best

Steve

[1] Gayford (2019: 181).

[2] The chapter is of course a pastiche version of the film title Desperately Seeking Susan. The tendency to find analogues that are both intriguing and accessible to a readership is another reason I love this writer. The plot of this film has more than a little to add to the theme of this chapter and the theme of ‘pursuit’ (seen not only as a form of chasing after something but also a searching for it – throughout the book.

[3] ibid: 181

[4] Information in ibid: 184

[5] Robert Rauschenberg cited ibid: 174. For the turtle see ibid: 168

[6] ibid: 96 & 101, respectively.

[7] ibid: 16

[8] ibid: 18

11 thoughts on “‘There is an odd but revealing phrase – ‘in the flesh’ – for seeing art in reality, not reproduction’.[1] What do we ‘pursue’ in the ‘pursuit’ of objects of art. Reflections on Martin Gayford’s (2019) ‘The Pursuit of Art’”