‘You have to begin there, with the oppression, to understand why the gay subculture is the way it is, otherwise your book is going to be another crock of academic shit.’[1] Felice Picano on why describing gay culture is neither value-free (if indeed any claim to ‘objectivity’ ever is) and that its values are political. Reflecting mainly on The Lure (1979 New York, Delacorte Press) – with a glance at The Book of Lies (1998 London, Little, Brown & Company). A sequel to my Like People in History blog.

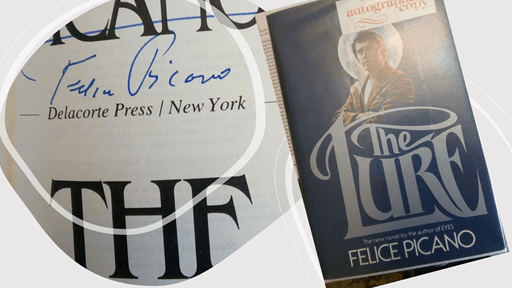

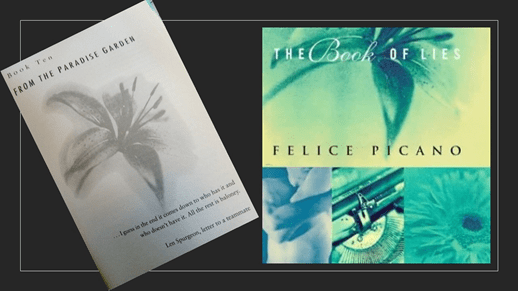

Steve’s NOTE: I think I run out of steam in this piece and it is more broken-backed than I had intended. However, any changes I make will just be tinkerings since I have doubts about where my ‘argument’ (if there is one) is going and whetber I really want to go there myself. Feedback from people interested in any aspect of this is welcome.

When The Lure was reprinted as a paperback in the UK (by the Muswell Press in 2019) Picano, in his 4-page Introduction to that new edition, takes special care, writing as it were with gnomic suggestiveness, about the importance of these novels to each other. In writing of The Book of Lies he says: “… with droll echoes and infra dig references to the earlier book, a novel that for a variety of reasons could not possibly have been written without The Lure coming first’.[3]

It is gnomic because it doesn’t tell us why exactly the novels are ‘close’ in other ways than in both being, in a way but an obvious way, a new genre built on pastiche – the ‘academic mystery thriller’. So whilst The Game of Lies once recalled A S Byatt’s Possession to me – in which spoof academics turn spoof detectives – I wonder now whether she too weren’t as influenced, were that possible, by the earlier 1979 novel as by her conscious influence from John Fowles The French Lieutenant’s Woman.[4]

But there are other reasons why the novels are close and why they set out to undermine academic discourses that try to capture what was like to live within an emerging gay culture (I think no-one should use the term ‘subculture’ now with its hint of the subaltern). But perhaps, more pertinently and interestingly, it is about what it is like to take on ‘a self’ from within a culture. In my view, this novel is very much a novel of identity not because it explores ‘gay identity’ as if it were a given or a-priori entity which pre-exists culture but as an experience in becoming, or emerging as, what you are only by virtue of acknowledging and accepting, as if by choice, that process. For me this gives the novel at least two strengths. First, it steers clear of essentialism in defining ‘gayness’. Secondly, it with some panache it embraces (from a time well before the word ‘queer’ was given this meaning in queer theory) the view that queer sexualities need not be exclusive, and, if they are so, show that there is an element of existential choice in the matter.

I felt this when I read the novel but it is far from a discovery (I was to discover in searching the literature). For instance Bergman’s major study from 2004 says quite assertively, if with surprise in his voice, that: ‘The Lure is closer to some of the basic tenets of queer theory than one might expect of so early a work’. The tenet Bergman picks out is implied in his statement that The Lure ‘dramatizes how sexual identity is a product of society, a phenomenon that grows out of the need to classify desire’.[5] Now this tenet of social constructionism is not what I mean by the novel’s likeness to queer theory, which is not that the validity of sexual identity as a concept should be questioned but that it is not a mere given of either our nature or nurture as human beings. It is a potentiality that has many possible forms alike in nothing but their rejection of imposed norms.

In 2018 the gay press was not so sure. Aaron Hicklin, in the online gay magazine Out, argued that that the title of the book referred to the fact that the main character’s key role was to ‘lure’ not a criminal underworld imagined to live beneath ‘gay subculture’ but a largely heterosexual readership attracted to crime novels: ‘ using an ostensibly straight protagonist as a lure … [for] heterosexual readers for whom a flagrantly gay novel would, even in the late ’70s, have been too much of a provocation, …’. He goes on to describe the character, (Noel Cummings) as enacting the equivalent of a sexual seduction of such readers technically as ‘a great distancing device that slowly reeled them in to New York’s gay underbelly’.[6] A more binary world of ‘either / or’ identities is harder to imagine than this and hence it compounds the limited and definitely non-queer take on the novel, when Alison Flood in The Guardian uses this very quotation and words to misread Picano’s own summary of why Cummings is initially a ‘straight’ character.[7] Flood is much more interesting when she pointed to other ways in which readers were neither seduced, or even mildly titillated by the sexual content of the novel, not because they had been inveigled into its sexuality but because they felt that it made gay life look extremely tawdry and unseductive and therefore unsellable to the heteronormative readership (straight and gay) of novels:

The Lure was hugely controversial with … some gay readers because Picano, in his words, had “exposed what I called the dirty laundry of gay life, the whole night-time scene. In order to get mainstream acceptance, a lot of organisations said we should never show that side. My feeling was, I’m a modern author, I need to show what life is like, the good side and the shady side. I absolutely stand by that.”

…[8]

In fact, I think Aaron Hicklin’s more recent take on this novel less accurate than Bergman in 2004, although neither really takes the novel as seriously as I would do. For what it’s worth my view is that Picano plays with the need of some men, for whatever rationale (to spy on anti-gay gangsters in The Lure or to qualify as a ‘gay writer’ whilst not being, strictly speaking ‘gay’ in The Book of Lies), to play roles in gay life, and even in gay sex that is either imagined, real or a combination of bits of both possibilities. For instance, the other characters in The Game of Lies only discover that good-looking narrator, Ross Ohrenstedt, is straight when he discovers (private as the discovery may be) genuine desire for a man, which he may never fulfil. After all the literary role-play, this book of lies and games ends with the narrator admitting to himself that, though he might ‘live out the rest of his life as a conventional heterosexual’, he has met in the cusp of between fiction and fact, ‘the man I was “saving myself for”, and whom I’d come to utterly desire’. The atmosphere in his fantasy seduction by the fictional-factual image of a baseball player called Len Spurgeon is suffused with the odor of a cologne he latter learns to be named ‘Guerlain’s du Coc for men’.[9] There is something here of the joy which both the reader and Noel Cummings discover so much about the outward and sensible (signs detectable by any of the human senses) but here to the sight, as Noel assumes his ‘disguise’:

Noel undressed quickly … when Vega stopped him with a pained expression.

“Oh, man. Nobody wears fucking underwear anymore. Chuck em.

…

“… That turtleneck’s gotta go, too. …”

What I take to be strong ironies, especially in The Book of Lies in its playful mock-poetic prose, are ways of insistent through humour that we cannot accept simple binaries as a means of working in and with gay culture that are based solely on pre-determined (whether by nature, nurture or an interaction between them) categories that do not have very fuzzy boundaries indeed. Such jokes multiply in The Game of Lies, wherein Ross is accused of ‘attempted heterosexualisation of the works of the Purple Circle’ (the fictional version of The Violet Quill writers that included Picano, Edmund White and Andrew Holleran – its only survivors). His enemies ask, as was done, that he ‘leave gay work to gay academics’, whilst those very survivors include the most ‘closet’ forms of predators on women – like the oily Machado, Ross’s antagonist for preferment in gay academia.[10] There has never been a more consistent ironic take than this novel on the attempt to specialise knowledge, skills and values as a ‘gay’ OR ‘straight’ binary, nor a more convincing demonstration of the homonormativity that this establishes and the tendency of the latter once born to mirror and feed heteronormativity rather than challenge and queer its normative assumptions.

For me personally this is the danger of a fetishization of ‘gay identity’, whether it feed off genetic arguments or not, in that it denies a third factor in the determination of identity other than biological or psychosocial determinism which is existential choice rooted in political and ethical considerations, including duty to communities as they are constructed to support identities. Hence, the fact that Noel Cummings in The Lure chooses identity continually is not just a means of seducing straight readers from their straightness but as a reminder that is based on many determinations that impinge on sexual and cultural identity, all demand a choice, conscious or unconscious, of the consequence on self-definition. Thus Noel will constantly feel the appeal of Alana but chooses fidelity to Eric, despite the fact that he often thinks, and is often told to think that his thought processes and ethical decision-making is being externally controlled.

This is why, I would argue, this novel is obsessed (not always to its benefit or credibility even as a fiction) with the machinery of mind-control and pre-programmed behavioural control. Bergman takes this far too seriously when he insists that the novel that it shows, as if a novel could do this:

… that, through the exploitation of their psychological vulnerabilities, people can be programmed to act out orders they are not conscious of possessing. Indeed, the novel shows how we are all more or less programmed to act in ways society dictates.[11]

Much of the psychological machinery and pretension of this novel should be seen as at best a metaphor for discussing the balances between pre-determination and freer choice long debated in the philosophy of the mind. It also uses, as part of its cod-psychological thematic a way of seeing personal identity and consequent behavioural choices, a model of psychic dualism or ‘splitting’ based on models of an assumed schizoid human psychology that can be found in Melanie Klein and Ronald Fairbairn. In The Lure this schizoid state is called ‘the split’ and at the novel’s denouement Ross experiences ‘this time … for real’.[12] The theme of behavioural control is held in the psychological ‘dossiers’ that Whisper, the undercover agency which recruits Noel, has made of its members as a tool of coercive control and which in Ross’s case uses his ‘realistic fear that he and always was a homosexual’ (I try to mime the effect of the font change in the novel itself when it cites the dossiers in this quotation) to provoke to raise the contest in which he will decide to either identify as gay or not later in the novel:

Given that everything written about him was true, how in hell could Loomis [the Whisper psychologist and mastermind] conclude he was homosexual? All those years with Monica! His affair with Mirella. And one little drunken incident to unbalance it, to tip it. it was unjust! Unfair! Untrue![13]

I will return later to how this works and how it undermines rather than reinforces simplistic binary conception of human identity and over-deterministic theories of ethical choice like that asserted by Bergman in 2004 and cited above. Picano remains fascinated by questions of identity, often expressed in fable – as in the Len Spurgeon fables ascribed to Len in The Book of Lies by the better Purple Circle writers, or perhaps just those of Dominic de Petrie.

For instance, the 1981 fable, An Asian Minor, retells the story of Ganymede by emphasising not the passivity of a boy taken to do the bidding of the gods, but of someone who reflects on their experience and makes choices, as to which kind of divine lover he should aspire.[14] Apollo, for instance, turns out to be a wonderful lover and sexual experience but Ganymede learns that his own joy in sexual experience makes him realise that: “I’d been whirled far past the Sun’s influence, way past his control and scope by a force – dared I think it? – a force larger than him’.[15] And even when he meets an external larger force, in the shape of Zeus, he negotiates his own way to immortality in a manner suggestive of his self-conscious sense of an agency even larger than that of the Olympian Head God: ‘This was between Zeus and me, and frankly, it really was the only way I could see things working out, mutually loving though we may be’.[16]

And as in The Book of Lies, The issue of Noel’s sexual identity in The Lure is tied to the motives which convince men that they can write fairly and with integrity, ‘a book on gay life from the inside’. It is going to be he believes an account of the ‘social structures of the gay scene and its imitations and adaptations of general cultural mores’.[17] Yet, as for Ross, the necessity of the book lies in Noel securing income and status as a university academic through a tenured position. When asked much later by his ‘lover’, Eric, whether this ‘book is pro-gay’ he answers: “It’s neither pro nor con. it’s a study. You know with charts and tables of statistics”.[18]

My own strongest feeling about the connection between the discussion of how a writer does and should write ‘about gay life’ in both books is that writers do not have a right to represent the queer community, individuals and behaviour in writing without querying the actual reasons for which they are writing. This means that one must start writing not from a supposed objectivity in our subject-position as if it were free from other interests, even if we are gay. It must start with a value-led (an ethical) commitment to strengthening the right of gay lives to be defined in the social, economic and political conditions which make their lives what they are. Hence the chosen citation in my title: ‘You have to begin there, with the oppression, to understand why the gay subculture is the way it is, otherwise your book is going to be another crock of academic shit [my italics].’[19] This statement is by Eric again and it fights against the right of academics who are politically and economically privileged and therefore, whether gay or not, blind to how potential in gay lives including decisions about behaviour are limited by social, economic and political realities. It defends a life that only those privileged by a certain release from very real political oppression can find ‘so back street, so seedy, so sleazy’ and ‘underground’ and with ‘connections with crime’, in short a ‘ghetto’ of those oppressed by the law of the state. As Eric says: ‘Everything I do is considered a crime , and I am a criminal’.[20]

Only privileged or ‘valued members of society’ like ‘a university professor’ see themselves as free of those life determinations and associations. Because of that defined social role they can choose unconsciously not to make the ethical and political choice that identifies themselves with the wider diversity in the group or community that is outside social norms and their own comfort zone. This is what Noel must learn from Eric, who turns him from a lover acting his role to being it in a chosen if performative world that is under construction. This is I think what Bergman gets totally correct when he sees Picano ‘at pains to show how gay culture is in the process of being constructed’ and constructed through such giving up all pretence at not oneself being also part of a ‘voluntary ghetto’.[21] This is why I also agtree with Bergman that this aligns Picano in 1979 with a queer theory, rather than one of gay social identity, even though that theory did not exist as such at the time and certainly not outside the universities.

The Lure remains an exciting novel precisely because Noel Cummings is a kind of initiate in a rite of passage that releases him from individual identity, like sex with Apollo does to Picano’s Ganymede, and gives him access to a freedom to choose an identity aided by the various objects and motifs of ‘gay life’ as it is determined in the 1970s without interposing between himself and these objects and motifs a pre-prepared identity. It is this process that I think Picano explores through the machinery of psychological splitting in the novel, wherein identity is deconstructed before it can find any image of itself with which to identify. At the end of the novel this is dramatized by the personal fragmentation caused by taking illegal drugs that mix gender, body parts and deny long-term identity as if they derived from Ovid’s Metamorphoses: ‘changing shape and proportions with every second-long change of light or color (sic.) or detail of sound around them’.[22]

But shape-shifting does not require any more sometimes but performance or co-performance with others of what is unknown to their previous classifications of behaviour, like the acts he learns, ‘some of which he’d never even classified as sexual’.[23] He will confront performed androgyny in self and others , acting out of inappropriate (by his former standards) sex across age, gender and the mental control that divides fantasy from reality, words relating to actions hidden by ‘embarrassed silence’ during his adult development but which, ‘always excited him to think of. always excited any boy or man he’d ever known’. This is a queer world, one not acknowledged by the norms but yet experientially totally normal to any male irrespective of category. After this, he will experience the body of self and other (it can be either) as if both could be either or both Zeus and Ganymede at the same time: ‘The boy stood and slowly stripped down, then lay down next to Noel: lithe, androgynous, waiting, smiling’.[24]

In this world we cannot assume that we even know what either the self is or what experiences outside norms mean. Recalling his childhood, Noel realises that he has no centred self at all, no identity that was not also ‘someone else’s’ and that these someone else’s also differed as much from each other as from him:

Who would have guessed that the child he had been … would now be doing what he was doing, acting as he was acting, being who he was? Waiting for someone. Expecting a call from someone else. Thinking about yet someone else. Fearing, resisting, denying, desiring, avoiding, all the someone else’s.

He was no longer doing anything for himself, because he no longer had any self.[25]

In such scenarios, sex is an unknown because it is an experience in which ‘someone else’ connects in ways you could not know beforehand. When Noel thinks how sex would feel with ‘Randy’ he can only feel it through fragments of other ‘someone else’s’: ‘small, lithe Larry’, ‘himself in a mirror (‘classic narcissism), a woman he fantasises about or seeing ‘Eric’s mouth around his thumb’.[26] And in fact sex with Randy which he thinks is only possible if he fantasises ‘he was with a woman’ is an experience in which his ‘entire body seemed to be embedded in that point of him that was more tightly clasped than he could ever recall it being’:

… He seemed to be vibrating from inside out.

Inside him, it was if a dozen hands were opening and closing around Noel all at once.

This attempt to describe sex from within coming out is like the experience of so many ‘someone else’s’: it is decidedly queer and hard to categorise or even query. I said earlier I would return to why the theme of ‘splitting’ undermines rather than reinforces simplistic binary conception of human identity and over-deterministic theories of the aetiology thereof. The ‘split’ is experienced in this novel when Noel feels most aware of being controlled or ‘programmed’ and when he simultaneously fights the dictates of his programming. It happens thrice in three pages of writing which deal with the oncoming love he will eventually feel for Eric Redfern, ‘a very handsome man, especially if you liked that fair-skinned, fair-haired, but tough WASPy type […] charismatic, strong, well-built, masculine … and most important he was infatuated with Noel’. The split in this the prose itself: it shows you, on the first hand, that Noel is convinced that he must have sex with Eric to defy Loomis’ dossier of predictions, including that Noel will kill Eric, that arise from his programming and, on the second, that he actually is as infatuated with Eric as Eric with him. The conditional, ‘if you liked’ presupposes a liking that Noel is trying simultaneously to deny.

The ‘split’ means that Noel is still moving towards identification of himself as a man who chooses to be a member of exclusively gay male groups and a lover, sexual and otherwise, of men and Eric in particular. When Noel experiences the final split, that he thought Loomis predicted from the programme, he thinks he is killing Eric but he is not – he kills Eric’s assailant leaving a chosen identification as both ‘gay’ and Eric’s lover. That the choice of gay identity is a political and ethical one is I think suggested by this final affiliation to Eric: ‘We won, Noel. You and I’, says Eric.[27] It is ‘something deep and ready and longing inside of him’ that he feels in freeing himself from that deep oppression, making the right choice that proved he was not a mere automaton but the possessor of his own choices, in which his will has cooperated against mere determination and he has freely chosen a life not recognized by the police, law or social norms of heteronormativity.

There are deep fissures and flaws in Picano’s writing no doubt but I think we should still be reading him. I will be. He has things to say, queer people like me can still benefit from learning and he is compelling and writing for us – still!.

Your ever

Steve

[1] Picano (1979: 237f.).

[2] ibid: 415f.

[3] Picano (2019: x) ‘Introduction’ in Picano, F. (2019) The Lure (new UK edition), London, Muswell Press. vii – x.

[4] I believe Byatt considers Fowles a lesser literary historian of the processes involved in the commitment to public ears of early women’s writing and understandings of the consequences of sexual love for Victorian women than herself, for good reason, in that the French Lieutenant’s woman must struggle also to stop herself becoming John Fowles’ own male conception of woman.

[5] Bergman, D. (2004: Location 4294) The Violet Hour: The Violet Quill and the Making of Gay Culture New York & Chichester, Columbia University Press. Kindle ed. cited.

[6] Aaron Hicklin (2018) ‘Luring Them In: Remembering the Queer Novel That Broke Barriers Between Gay & Straight Readers’ in Out (Online) July 31 2018 7:00 AM EDT. Available at: https://www.out.com/art-books/2018/7/31/luring-them-remembering-queer-novel-broke-barriers

[7] Alison Flood (2018) ‘Interview: “I exposed the dirty laundry of gay life’: The Lure, the thriller that shocked America”’ :Felice Picano’s controversial story of a serial killer in New York was a huge hit in 1979 – but may also have provoked an armed attack on his home. Forty years on, he talks about his novel’. In The Guardian (Online) Thu 19 Dec 2019 12.08 GMT. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/dec/19/felice-picano-i-exposed-the-dirty-laundry-of-gay-life-the-lure

[8] Ibid.

[9] Picano (1979: 415f., & 417 respectively). Guerlain is a genuine perfume brand (https://www.theperfumeshop.com/guerlain/b/35) – although I cannot find the du Coc fragrance. Anyone know?

[10] ibid: 414f.

[11] Bergman (2004: Location 4288)

[13] ibid: 202f.

[14] F. Picano (1981) An Asian Minor: The True Story of Ganymede (New York, Sea Horse Press)

[15] Ibid: location 515

[16] ibid: location 770

[17] Picano (1979: 169f.)

[18] Ibid: 310

[19] ibid: 237f.

[20] ibid: 237

[21] ibid: 237. Again this term is that of Eric.

[22] ibid: 378

[23] ibid: 270

[24] ibid: 98

[25] ibid: 361

[26] ibid: 126

[27] ibid: 409

10 thoughts on “‘You have to begin there, with the oppression, to understand why the gay subculture is the way it is, otherwise your book is going to be another crock of academic shit.’Felice Picano on why describing gay culture is neither value-free and that its values are political. Reflecting mainly on ‘The Lure’ (1979)”