‘If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?’.[1] Waiting for the return of a long-awaited (and expected to be popular) art exhibition and the fate of those who wait. Reflections on art exhibitions and the substitutes for them in and after lockdown based on reading the 2020 translated novel by Catherine Cusset (translated Theresa Lavender Fagan) David Hockney: A Life London, Arcadia Books & Martin Gayford’s (2021) Spring Cannot Be Cancelled: David Hockney in Normandy London, Thames & Hudson.

There ought to be no connection between the two books on which I reflect here I suppose, other than the fact that they both concern David Hockney. I bought them after the disappointment of finding that I could not attend the new Spring Hockney exhibition at the Royal Academy when I was in London in May (and it seems further than ever from Durham now travel becomes possible again after a long pause) because it has long been sold out. During lockdown I have bought the catalogue of exhibitions that were cancelled (such as Cézanne: The Rock and Quarry Paintings, for instance, which one day I will get around to blogging upon) or delayed exhibitions. Hockney exhibitions do not wait long before they are filled full and thus Turner, Rodin, Lewis Carroll and John Craxton will have to do for us in May.

However, having now read both of these books there is another less contingent link. In Spring Cannot Be Cancelled Hockney tells Martin Gayford about his fascination with Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past and how this led him to the Grand Hôtel in Cabourg (Proust’s ‘Balbec’), ‘…, it was with Catherine Cusset, who has written a novel about my life’.[2] It is this link with Proust which is possibly the subject of conversation that day in the Grand Hôtel and is certainly the artistic model to which Cusset in her novel feels Hockney aspires, in which Peter plays the role of the ongject of Swann’s love and Albertine Disparu.

…, David wondered whether his own work didn’t strive to be as ambitious as that of Proust, whom he had reread over the years. Proust’s opus was built like a cathedral around a spiritual quest: the search for lost time – the search for a link between our different selves, which kept dying one after another.[3]

It is this fascination with Proust’s conception of art as a model of how life is metamorphosised first as a project in our memory and then in art that makes the most interesting connection between these two books. It is, as we will see, the means by which Hockney has begun to reshape the significance of his own work, art and life in older age. For there is a vast difference in the conceptualisation of artistic ‘vision’ between Hockney’s conscious embrace of literary ambitions (which call both upon all of the senses, emotion and cognition – memory and thought as well as perception – and the narrative dynamics of motion in time) and those purely visual models of graphic art promoted in the history of art. It is the equivalent I believe in asking art to return consciously and openly to the use of multiple media and processes in its production: ones that offer a handle to the widest scope of reception, distribution and understanding.

I would like to examine then several themes of connection but in the interests I think of registering how exemplary a take on art and biography as a mode of accessible and significant art criticism is Martin Gayford’s lovely book. I want to do this because I started off reading it thinking it merely trod roads that both Hockney and Gayford had trod too many times before to add anything new. I ended up realising that was exactly the wrong understanding of how this book worked but with an appreciation that those roads had to be reprised precisely because they were the base for something entirely different, a justification of art that was unembarrassed by the appeal of figures, pictures (rather than paintings) and stories and was therefore democratic, without being patronising, in a way the elites of art history and art criticism find it difficult to understand, because it pays little attention to the constraints they offer up as thought.

So this blog will examine these themes – hopefully in a relatively organised way – in this order. The first is that I started off as thinking as already exhausted by previous publications by Hockney and on Hockney by Martin Gayford:

- The debate on ‘perspective’ in art and, to a lesser extent the use of optical aids by artists throughout history and its relevance to widening the perspectives. This theme is conscious too of artists’ reflexive engagement with the processes involved in making and evaluating pictures that proceed from their actual engagement with a wide range of media, technical or craft processes. This was, after the 2016 book History of Pictures, by Hockney and Gayford clearly a major issue for the artist in defining the purpose of his continuing work.

- The extension of the narrative mode of the Bayeux Tapestry into the understandings offered by a second model of art associated with Normandy, and the repeated promise of spring under threats to its loss in mortal time; that of Proust.

- ‘surface’ and ‘depth’ in visual art, even that denominated abstract art, in terms of motifs of the flow and stasis of water, the temporal aspects nature of our experience of light and lighting and colour and the persistence of how we ‘picture’ landscape in and through time and change, even of weather.

_________________________________________

One: The debate on ‘perspective’ in art

We can start by looking back then on my original thought on beginning to read Gayford’s new book that it then felt to me once as too much a rehash of older themes. Even the title of that earlier book, History of Pictures, is a means of challenging the pretensions of the academic discipline we call the History of Art, which very usually capitalises the terms ‘History and ‘Art’ in order to denote they are conceptual or ideal abstractions. This is a challenge both Hockney and Gayford have taken on over numerous publications, associated with the promotion of wider international art forms in different media, notably Chinese scroll painting. The latter form had long been seen by Hockney as the locus of painting with unashamed roots in multiple variant perspectives and a narrative or otherwise moving set of foci that Cusset dates back to Hockney becoming acquainted with notions of “Sequence and Moving focus” in George Rowley’s Principles of Chinese Painting.[4]

The disregard of different ways of conceptualising space and time are raised too in Cusset’s novel. His suggestion that that tradition was from the Italian Renaissance onwards at the mercy of a technical understanding of HOW to see the world based on the invention of the camera obscura. The camera obscura was the origin he argued of the imposition on art (but not all art – think of Tintoretto) of an ideology of a world that can only be represented from one viewpoint, and hence of a perspective governed by the notion of only one vanishing point. Hockney’s point about the camera obscura was misrepresented from the very beginning by the art grandees and self-appointed dragons sitting on the treasure pile of academic history of art. They took it to mean that Hockney was insisting that great artists such as Caravaggio used cheap technical tricks to make art and were concomitantly being accused of not being able to draw merely because, as Linda Nochlin suggested, Hockney couldn’t draw himself. They implied he used theoretical belief here as a means of levelling the playing field between great art and his art.

Cusset’s novel dramatizes the attacks on him by a history of art establishment including Susan Sontag, Linda Nochlin and Rosalind Kraus, which to Cusset’s Hockney avatar feels like a trial by ‘a college of cardinals trying to decide if they should condemn a heretic to the stake’.[5] The scene of the ‘trial’ was a symposium which actually took place in New York in December 2001. The evidence for the ‘prosecution’ but also, correctly read, for the defence was his 2001 book Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters. A contemporary Guardian report by Peter Robb suggests to me that the crime for which he was tried was also one in which art specialists defended their entitlement to be privileged reporters of the truths of art history – a privilege in which the academy stood in a position of superior insight over even artists themselves. Was it that this establishment felt that their knowledge, skills and values, based entirely on evidence from within a limited Eurocentric tradition were being challenged? Robb in his Guardian article says of the new truths offered by this book, as for some of its speculations: ‘It took a painter to show us’.[6] Imagine then the pain in the halls of academia at the disrespect against themselves such thoughts implied.

Cusset imagines Hockney’s viewpoint as he stands up to speak against concerted attack on him that had been received rapturously by its audience:

What taboo had he broken for art historians to stand up as one against him? What were they afraid of? Their desire to keep art in an ideal world had something fascinating about it. David felt a bit like Robin Hood in his attempt to give art back to the people.[7]

That Hockney is imagined as casting himself as Robin Hood here feels slightly comic given the eccentricity of Hockney’s politics. However, I think his stance against art elites mattered because such elites, intentionally or not, continually ridicule attempts to share understanding of experience of art as widely as possible and bring to bear against such views an over-the-top artillery. Of one thing one can be certain: these theorists of modernism would question any convention other than the ones that gave them power and social authority. The clever Northern English grammar school boy is soon put in his place in this scenario but not without any reader of this novel feeling free to ponder on what elites feel to be under challenge in their subject positions here.

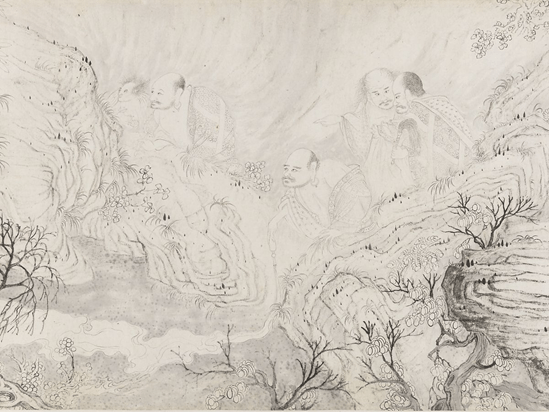

This same challenge emerges with regard to the new pictures of a Normandy spring that forms the subject of the upcoming Royal Academy exhibition this year. But it emerges too in relation to a model provided by a great but under-estimated (in Hockney’s view) Romanesque artwork known as the Bayeux Tapestry. Gayford explicitly likens this great work to Chinese scroll work.[8] Both artforms pose various forms of challenge to academic art history (in terms of their motivation, mode of representation and engagement of and with the world, and their media and format): ‘The Bayeux Tapestry represents the world in a way that has been regarded as ‘primitive’ or flatly ‘wrong’ in the Western artistic tradition since the Italian Renaissance. It has a different relationship to space and time’.[9]

Two: The extension from Bayeux Tapestry into the narrative mode of Proust.

There is a grand obviousness about the way that time perspectives are mixed in the Bayeux Tapestry as this image in it (shown above) of Halley’s Comet, which was taken, the scroll insists to betoken the Norman victory over Harold Hardrada. Space and time are fluid and rhythmic here – often disbursed in some pragmatic form of spatial design appropriate to the medium (its use of different lateral registers for instance) but always also with narrative and temporal significance. Perspectives are malleable to those needs and to those opportunities to seek meaning beyond the object. Gayford says Hockney was driven by his ‘appetite for pictorial space – wider and wider vistas, in all directions, up and down and side to side – …’.[10] And Hockney feels that animal and human animal appetite is the source of the long duration in which this Tapestry, associated with the ‘low’ craft of embroidery by women, was regarded ‘as factual reportage rather than masterpiece of art’.[11]

The hierarchical elements here, touching on gender and social power and status, do not apply however to the way in which Hockney’s interest in narrative visual art – or to be more precise moving, shifting and varying foci of interest – drew him to spring in Norman ‘Balbec’ in Within a Budding Grove and that meeting with Cusset. He was drawn I’d argue to the model in those fictions, in which the Grand Hôtel in Cabourg is metamorphosised, because of Proust’s innovative narrative method. Of course, no-one says Proust is not ‘high art’ but then no-one is quite as rigid in their prescriptions of meeting the demands of literary commentary, given its innate democracy (at least among the literate but not only those since oral story-telling matters too) as they are of ‘fine art’. In the latter contingency factors of power, fluid resources like ‘money’ and notions of ‘possession’ (satirised by A.S. Byatt but in terms of written literature in her wonderful novel Possession) have a much deeper hold on even the academic traditions (and perhaps if Byatt is correct because of those traditions) of the history of art and its continuing love affair with connoisseurship.

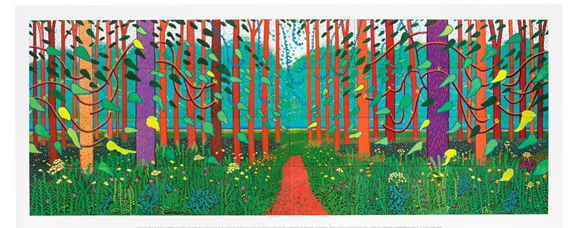

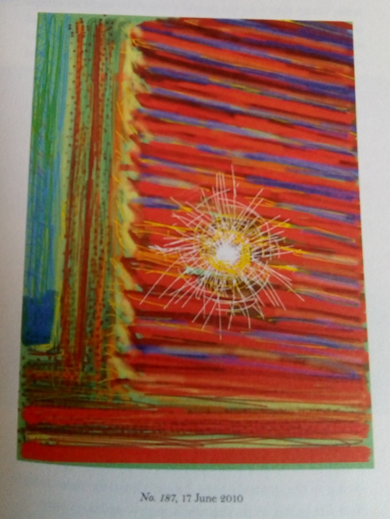

Now it is impossible without seeing the way the art works are represented in the space and time of the Royal Academy exhibition or, as a second best, in the concertina format of its catalogue (mine is ordered) to talk about how Hockney attempts to realise that. A page opening from Gayford’s book will show how impossible it is to illustrate constantly moving focus in a medium dominated by the idea of fixed focus that even attempts to persuade the reader of the temporal nature of the act of reading.

Books, as this shows for one thing, flatten perspective and some temporal and spatial considerations, if not all, as much as cameras do. In my final section I want to show how some key motifs in Hockney’s new art show how and why Proust’s view of narrative and significant time matters to him, however here I look only at how Proust himself is represented in Gayford’s book. Gayford deals with Hockney’s explicit references to Proust over 4 pages in the final chapter.[12] In fact the material is rich in the unsaid. That Hockney’s return to the novel – by reading the early Scott Moncrieff translation (the one I read it in first in the 1980s) rather than the most recent one – is to ‘the Sodom and Gomorrah part’; that memorial to effect of time and change on queer people like the Baron de Charlus and Jupin. Yet Gayford does not pursue this possible theme here but that of its innovative focal multiplicity as storytelling:

… it deals with the relativity of time and of perception. Everything is seen at a particular moment and from a particular angle. … It is a series of moments, and the climax comes when the narrator grasps how the intricate mosaic of his life fits together. It is … essentially a Cubist way of looking at the world, integrating numerous points of view and instants of time into a whole.

ibid: 245

But as well as the obvious link between this and Hockney’s view of Chinese scroll work and the Bayeux Tapestry is that this is, in the book, also treated in terms of visual art as the comparison to Cubism shows. That linking theme is an ongoing elaboration of Hockney’s enduring insistence (to which the history of art continues to turn a blank eye) that, “we see with memory”.[13] It is a complicated interaction however – that of memory and present perception. Gayford (and it is unclear here whether the commentary is his own or the reported speech of Hockney himself [and perhaps it doesn’t matter]) discusses this in retelling how Proust’s fictional artist of the novel, Bergotte, revisits Vermeer’s wonderful View of Delft (see below) to see again in it the little patch of yellow wall (‘petit pan de mur jaune’).

In effect, this is a brush-mark, the kind of touch that Monet might have applied to one of his haystacks, or Hockney adds to a painting or iPad drawing. it is a note of colour that makes the picture sing, that works for visual reasons that defy analysis.[14]

Three: ‘surface’ and ‘depth’ in visual art coloured in time.

The concern with detail of technique and the representation of space and time in the ‘petit pan de mur jaune’ helps me move on to looking at how this subtle book conveys the really innovative work that Hockney is now still doing. People with any interest in the academic study of the history of art should turn off now. This is the kind of material that earned me remarks when I studied on a History of Art MA for the Open University like: ‘you should rather list the views of others from different contexts than your own’ and so on. Let’s let the lords of subjective misrule reign only for the rest of us then.

Time and space are contentious matters in world art because they are the very stuff of representation, exposing a lack of match between the world which represents that which is represented. What takes an instant in the latter, such as a splash of water, may take a lot of time and effort in the representation and metamorphoses involved in art.[15] A vast space especially depth of space might take up little or no space on a canvas, so much so that it is felt rather as if it were an aspect of motion (or e-motion) than physics. To talk about ‘distortion’ in art is a kind of misnomer, therefore.

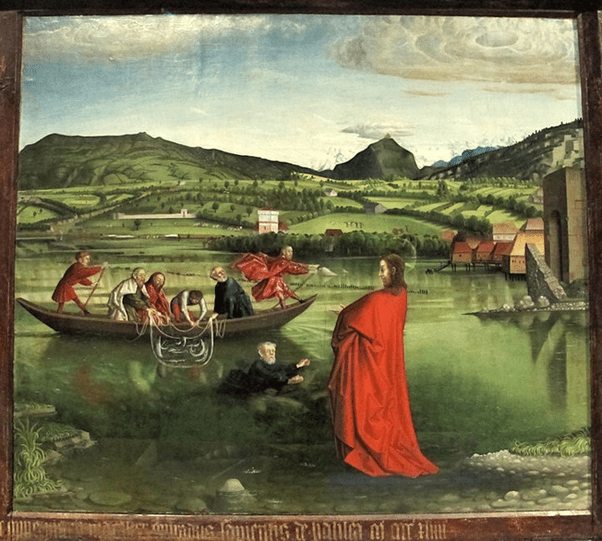

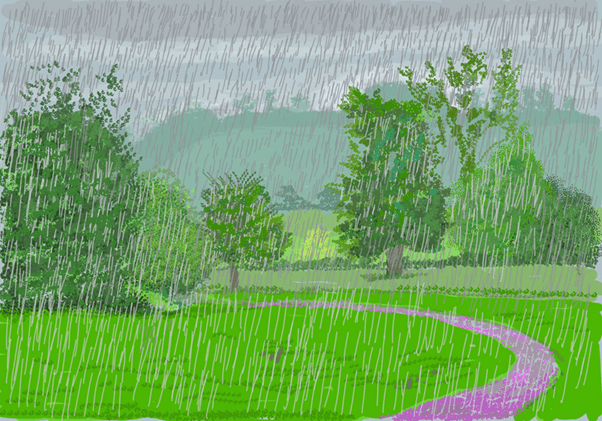

The representation of rain for instance is not just a matter of comparing how this is done by Hiroshige (in Sudden Shower over Shin-Ohashi Bridge and Atake (1857)) and Hockney in this new series (see No. 263, 28 April 2020 in this new work for instance) of which the comparison is at first done.[16] Instead it raises the whole problem of what we mean by ‘surface’ and what we mean by ‘depth’ in art. Hockney believes moreover that Martin Kemp is perhaps the only art historian associated primarily with the universities who would understand this and who demonstrated it by sending to the artist, in response to receiving the last named raindrop drawing, Konrad Witz’s The Miraculous Draft of Fishes (1444).

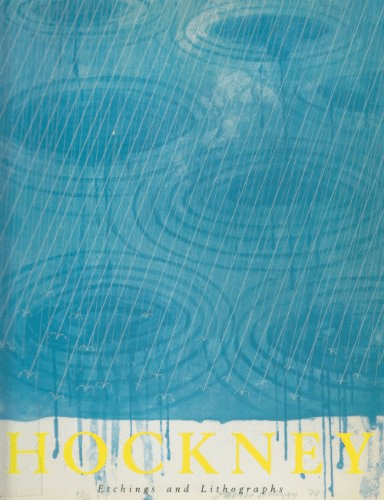

Water interests artists not just because they might need to represent it but because it raises all the important problems of space and distortion and it does so because, despite Clement Greenberg, it is only an issue of the distribution of space across a ‘surface’ to the mind-numbingly literal. The best extension of the ideas opposed to Greenberg arise in the cooperative analysis of the 1973 work Rain, which appears on the cover of Marco Livingstone’s 1989 collection of Hockney’s Etchings and Lithographs.

For Hockney this picture is recalled by both Monet’s Nymphéas and Rousseau’s Les Rêveries du promeneur solitaire and both concern the description of mental constructs in memory. And the constructed nature of the image here is the point – where everyday perception in context, art object, art technique and perceptual psychology all intersect.

Hockney’s Rain made a visual pun on the watery medium that he was using – ink – and the fluid nature of his subject. but more than that he was making another such rhyme between the flat sheet of paper on which his image would be printed and the surface of the water. … both have a two-dimensional surface – but it is possible to see beneath it, behind it, or through it.[17]

The study of other temporal aspects of nature other than its ‘flow’ (and here the writers utilise the existentialist-phenomenological psychologist, Csikszentmihalyi’s (1975) ‘flow’ theory) are the stark basis of it in light, dark and shade variation.[18] There is too much that is too rich to develop here but it speaks through in the Normandy moon and garden works.[19] Instead I want to finish by looking at the treatment of the old disegno-colore paradigm (charcterising comparisons and contrasts in Renaissance painting but revisited in a different way by Fauvism). The genre that Hockney explores this in of course is ‘landscape’, that song of praise to space and time, and with only a slight reference to classical tradition and Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony the literature and music of change.

Gayford’s new book is and is not a biography but in it two really important biographical considerations weigh – the effect on the visual artist by increasing decline of the powers and pleasures of his physical body, especially in the realms of hearing and sexual experience, and the tragic loss of his young assistant, Dom – yet another hard to explain gay male suicide ignored so widely, which shows that the story of queer liberation is far from an achieved one. Neither life-theme becomes a major one but they lend dark but beautiful tones to the colouring of the landscape of Hockney’s life. And colour has that character in this book – an attachment to something deeper than its surface effect. Take this piece of prose from Hockney itself. Though ostensibly about colourist practice, it is also about time and its passing – its physical effect on paint, that abstraction we call colours and human endurance, and life and memory as an aspect of the changing social taste in views:

But all colour is a fugitive thing, isn’t it, even colour in real life? It’s always changing. Even so, some painters have always made their pictures to last, even when using colours such as green, which are often the most changeable. … Green was a fugitive colour for a long time, and in many older pictures it turned brown. Constable was one of the first painters in the nineteenth century to use a lot of it. When one of his landscapes was put in front of the RA hanging committee, someone exclaimed, ‘Take that nasty green thing away!’ …[20]

As Gayford adds, the tolerance for green had been worn down by a symptom of passing time which was read as an artistic convention that determined what is tasteful. I am asserting I suppose that this book is richer than it might appear. It will be dismissed as ‘popular’ in tone and purpose but that tells us much about the persisting decay that is academia and the journalism dependent on it and its Ph.D and other Academy conventions.

I feel the greatest moment in this book among many may be for me the way in which abstraction is ripped apart to reveal the dependence on the figurative and the pictorial. This is perhaps at its most obvious in the treatment of Ad Reinhardt’s ‘unreproducible’ paintings.[21] It is at its most suggestive – though deeply subjective and therefore not for academics these days – in treating of the landscape origins of Mark Rothko’s imagination as an abstract colourist.[22] His comparisons with landscapes important to Rothko via Munch to his own pictures of light in the present Normandy pictures recall that in Bridlington, Yorkshire, make me weep and smile and feel incredible awe at the same time.

I have registered my interest in return tickets for the Hockney exhibition whilst we are in London. Come on Royal Academy. Spoil me! Please!!!!!!! Would love any feedback from anyone who gets to see it.

All the best

Steve

[1] l. 70 (final line) of Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) Ode to the West Wind written in ‘1819 in Cascine wood near Florence, Italy. It was originally published in 1820’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ode_to_the_West_Wind). Poem available at https://poets.org/poem/ode-west-wind

[2] Gayford (2021: 248)

[3] Cusset (2020: 132)

[4] ibid: 126

[5] ibid: 146

[6]Peter Robb (2001) ‘a Candid camera: In Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, David Hockney reveals how artists caught nature with lenses and mirrors. It took a painter to show us, says Peter Robb’ in The Guardian (Sat 20 Oct 2001 03.44 BST). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2001/oct/20/highereducation.news

[7] Cusset (2020: 146)

[8] Gayford (2021: 96)

[9] ibid: 97

[10] ibid: 95

[11] ibid: 97

[12] ibid: 244- 248.

[13] Hockney conversational observation cited ibid: 247

[14] ibid: 246

[15] I’m referring to Chapter 10 of Gayford (2021: 182ff.), ‘Several smaller splashes’ which also deals with A Bigger Splash (1967).

[16] ibid: 182 – 185.

[17] ibid: 196

[18] see ibid: 202 – 204

[19] See for two instances only ibid: 156f & Chapter 16 ‘Full Moon in Normandy’, 265ff.

[20] ibid: 179

[22] ibid: 259

[21] See ibid: 164ff.

3 thoughts on “‘If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?’. Waiting for the return of a long-awaited (and expected to be popular) art exhibition and the fate of those who wait. Reflections based on reading the 2020 translated novel by Catherine Cusset (translated Theresa Lavender Fagan) ‘David Hockney: A Lif upe London’ & Martin Gayford’s (2021) ‘Spring Cannot Be Cancelled: David Hockney in Normandy’.”