‘I see him. Thomas Müntzer! And he is no longer the little Thomas of before, … the son of the dead man, no longer even an object of study’ he is a man, any fleeting life’.[1] What or whom is the subject of Éric Vuillard’s The War of the Poor? Reflection on Éric Vuillard [trans. by Mark Polizotti] (2021) The War of the Poor London, Picador.

Sometimes you read a novel and have to stand back as ask: ‘Now what was that about’? In some cases you might even be unsure what kind of novel or piece of writing you have just read – even though you may, as I did this, have enjoyed it immensely and been thoroughly impressed by the experience. The judges of the International Booker prize have committed it to their list of this year’s contenders, describing it as a ‘dazzling piece of historical re-imagining and a revolutionary sermon, a furious denunciation of inequality’. Yet does that answer the question I wanted to ask? I think that instead of that it gives up on the question, except to stress that the book’s effect is to denounce inequality. But then, why denounce inequality in a short text that is over-rich in its potential provision of contexts – biography, history, politics, religion and fiction?

Paul Burke, reviewing the work for NB Magazine on November 4th, 2020 seemed to know what it is about: ‘This is a story of belief, of emancipation of the spirit and the body, of ideals, of corruption and religion. …. The message is fight, now as much as ever, for a better future’.[2] But, truth to say, this doesn’t solve any problems at least for me as a reader. It certainly describes in a rather abstracted way the fact that this novel may be about ideas of change involving ‘ideals’ such as freedom and to assert that the novel does not situate itself entirely in historic time to do so. It is about, we gather how the call for a better future , though resonant in episodes of history must be taken on now, in the reader’s temporal present.

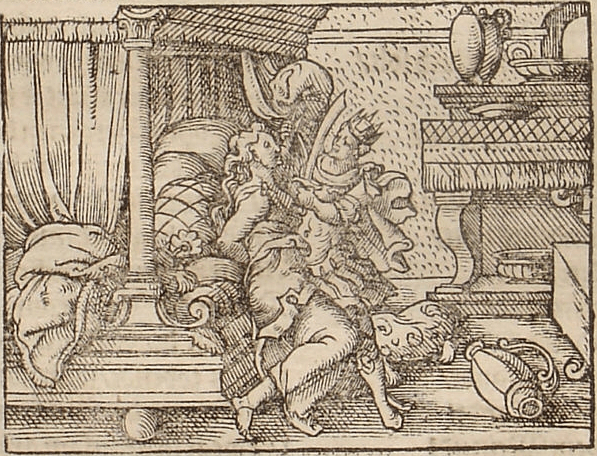

It certainly ends with the writer projecting themselves into the future – projecting a ‘victory’ of which they shall tell. Moreover, it continually seems to want to have done with the past, even elements of it in which he has seen the seeds of what might have been that future. The revolutionary Protestant cleric of history, Thomas Müntzer, is the person whose story is told over most of its pages but he disappears from the story not just by dying but by being ‘worn out’ and then fragmented, even more than the physical realities of his case might bear witness![3]

Historical event in this novel undergoes strange metamorphosis, as if the elements that constituted it were still in question and yet to be decided, like their ultimate significance. Let’s take as an instance the treatment of the invention of printing by Johannes Gutenberg, who is not mentioned in the book though his place of origin (and of the printing press as history reports), Mainz, is. The story starts thus:

…, a molten substance had flowed, flowed from Mainz over the rest of Europe, flowed between the hills of every town, between the letters of every name, in the gutters, between every twist and turn of thought; and every letter, every fragment of an idea, every punctuation mark had found itself in a bit of metal.[4]

Signifiers here are allowed to float free from what they signify and become also in a sense the signified, which is the flow or motion of letter, words and thoughts, as if these words from very distinct domains of reference were in a continuous chain of meaning and being. Of course a reader can equate ‘a molten substance’ with the liquid form of the ‘metal’ it becomes at the very end of sentence but before we get there it must be an unspecific substance that might or might not have physical form but may be merely a metaphor – equally a flow of lava in a geological change event but maybe also some ‘hot’ and turbulent abstraction that has a purely mental being.

We know this ‘substance’ divides up ‘names’ (signifiers of things or persons) as it flows between them and perhaps also makes them begin to cohere. Physical twists and turns work like thought as channels of the crooked motion of something that could be both abstract and physical – is it history itself? I cannot see the French original but the use of the term ‘gutter’ in the English translation suggests the world of expanding cities, and the flow of waste they generate, and the term ‘gutter’ used in page design in printing. This rich and beautiful passage (I find it very beautiful) is so characteristic of the novel’s refusal to cohere around a single subject – not least the apparent central character ripped from history and fictions wound around history, Thomas Müntzer.

I chose the quotation I cite because at a crucial moment, when the narrator sees Müntzer’s broken body replicating the fate of his father as the victim of an authority that refuses challenge to its entitlements, he realises that perhaps he isn’t seeing Müntzer, ‘name divided’ from the rest of humanity merely by the accident of being selected out of the lives of common humanity (as perhaps ‘even an object of study’) and divided by some ‘molten substance’ from it. Is what the narrator sees actually really ‘a man, any fleeting life’?[5] For me, this author yet again shows here that the purpose of fiction is to champion a victory in the longue durée of those denied the wherewithal in life and in the attention of the culture of the written, writable and published/publishable lives by the ‘order of the day’. A truly radical writing again that has every right to claim it will be there when the poor are victorious over the ‘order’, authorities and long inscribed entitlements that oppresses them.

And hence it is totally just that this approach is very selective in the history it tells. Indeed I feel it rather telling that a reviewer as otherwise sympathetic as Paul Burke needs to tell us that these few pages select only moments from history and weave them together which are in the master narratives of the culture and in supposed ‘objective’ evaluations are seen as mere historical oddities, as indeed is the ‘German’s Peasant War’ of 1525 associated with Müntzer. These oddities include the 1380 uprising that started in Colchester, England, supposedly under another name divided from he mass of dynamic life which Ball knew, Vuillard insists, was actually what gave him meaning:

His speeches were stitched together from everyday proverbs, common morality. But John Ball knew that the equality of souls had always existed in the leafy thickets, he could feel it guiding him, making proclamations. They nicknamed him the ardent prior of the pickets; he was frightening.[6]

Again I find the exchange here between the process of names (or nicknames) emerging out of history that actually was the motion of a grand and just cause emergent from the bottom up, in a society determined to believed it had a top and a bottom, truly beautiful. In moments of history those people whose position among the ‘poor’ was enforced from above begin to know that they possess some knowledge worth having and that the entitled will distort in order to justify their entitlement: ‘for those weavers knew that if you pulled at a thread, the whole tapestry would unravel; the miners knew that if you dug deep enough, the whole tunnel would collapse’.[7]

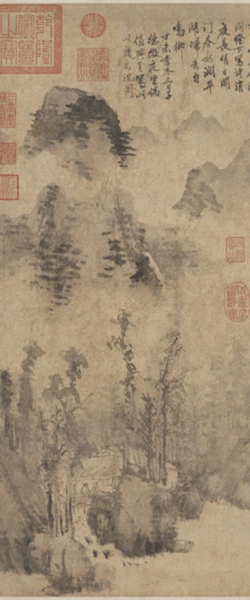

And what the subject of this novel is will always be a matter of dispute if a culture refuses to connect the insights won through patience into the nature of the passage of time and the inevitability that all the order and authority we see in the world will in the event be seen to have ‘folded in on itself’ just as ‘in Cathay, the good Shen Zou’ did (on ‘13 November 1504’)[8] his illuminated textile scroll.

And most will see no connection between Shen Zou’s work and the reactionary response to Müntzer, represented by a ‘strange shiver’ felt in the body of Phillipp, the Landgrave of Hesse, ‘like a surge of antecedence’ when he was 5 on the same date and the pressing of the rights of the previously unentitled in the Reformation:

And even if you don’t give a shit whether or not the Chinese painter of rocks and birds had some mysterious kinship of the soul with the Landgrave of Hesse, fantasies are nevertheless one path to the truth. History is Philomela, and they raped her, or so they say, and cut out her tongue, and she whistles at night from deep in the woods.[9]

Thus Vuillard says: again so beautifully and savagely, but yet with a ‘commonness’ of idiom in order to show he for one ‘gives a shit’, as if he were Ovid reincarnated writing again the Metamorphoses, from where he takes the story of the rape of Philomela, for another age.

Let’s return to speculation as to why the Paul Burke, a distinguished academic historian, in his review chooses to see Vuillard as ‘selective’ in his re-telling of history. I would suggest that over the ‘order of the day’ hangs an ideology that misrecognizes itself as ‘objectivity’ and as NOT an ideology but that is why I think Vuillard argues that art must ever look to ‘fantasy’ to help with the truth of history and is what drives his perception that far from this book showing his selectivity and that of the left, it asserts that History as told is a version raped by the authority of kings and other powers that be. This is why this work acts like a huge joke about history that might also pass as poetry. At a time when the left is in the doldrums I could only smile with glee at the beauty of this Shen-Zou-like perception of small detail in a larger picture of the battle that decided Müntzer’s fate: ‘suddenly there was a rumble in the left wing – nothing much, mind you, but a tremor that spread from animal to animal, rider to rider, like a gentle breeze in straw’.[10]

And with a certainty that I have found rather depressing, living in a country without a detectable left intellectual position that has credence or life beyond the passivity of do-nothing-but-claim-the-fat-of-student-fees zombie universities, Vuillard asserts himself as a labourer in words against ideologies that forever hang on the virtues of transcendence, even when they mask themselves as popular religions and ‘aggressive theologies’ such as that espoused by Müntzer himself:

In reality, quarrels about the Beyond have to do with the world here-below. That’s all the influence those aggressive theologies still exert over us. The only reason for understanding their verbiage. Their impetuousness is a violent expression of poverty. The plebeians rebel. Hay for the peasants! Coal for the labourers! Dust for the road-workers! coins for the beggars! And words for us! Words, which are another convulsion of things.[11]

This concern with the substantiality of letter, words and thoughts is what gives resonance, not unlike meaning and a subject matter, I think to the passage I quoted near my opening on the spread of the revolution, which was the Gutenberg press, though that is but a symbol of how informed articulation becomes suddenly an entitlement of those from whom those with current power over them would keep from them. This hope that books can help an old oppressive order to rot as is appropriate to it surely lies behind the metaphor used by Vuillard to describe the proliferation of the Bible in the language of common people and not that of an educated elite: ‘And then the books had multiplied like maggots in a corpse’.[12] I wish I were still so hopeful that the old order can be defeated. <Sigh>

This is a magnificent book. Surely the front runner for International Booker Award!

All the best

Steve

[1] Vuillard (2021: 65)

[2] Paul Burke (2020) ‘The War of the Poor’ by Éric Vuillard in in NB Magazine – Online (4 November 2020) Available at: https://nbmagazine.co.uk/the-war-of-the-poor-by-eric-vuillard/

[3] ibid: 65

[4] Vuillard op.cit.: 2

[5] ibid: 65

[6] ibid: 13

[7] ibid: 7

[8] !504 is the date usually given for the scroll ‘Clouds Over the River Before Rain’ (see https://www.alamy.com/author-shen-zhou-clouds-over-the-river-before-rain-ming-dynasty-13691644-dated-1504-shen-zhouo-chinese-1427-1509-handscroll-ink-and-image360086401.html) but I do not know the significance of this specific date – can any reader inform me? it is on ibid: 45

[9] ibid: 46

[10] ibid: 58

[11] ibid: 54f.

[12] ibid: 3

2 thoughts on “‘I see him. Thomas Müntzer! And he is no longer the little Thomas of before, … the son of the dead man, no longer even an object of study’ he is a man, any fleeting life’. What or whom is the subject of Éric Vuillard’s ‘The War of the Poor’? Reflection on Éric Vuillard [trans. by Mark Polizotti] (2021) ‘The War of the Poor’”