‘ “Will you walk a little straighter?” said a clergyman I knew’.[1]: On Stephen “Tommy” Tomlin and why sexual categories can be so confusing when used to summarise a life! Reflecting on : The Bloomsbury Stud: The Life of Stephen ‘Tommy’ Tomlin by Michael Bloch & Susan Fox (2020) London, M.A.B. Available direct from publishers at: https://www.bloomsburystud.net/

In the eyes of commentators the life of Stephen Tomlin, known as “Tommy ” because his siblings. and parents, labelled him ‘Tom-Tit’ as a child, Tommy’s sexual life takes tragic prominence over any contribution to literary or art history.[2] Reviews of this book have tended to compound this tendency, as if a life could only be justified by surviving works in the public domain. By this standard, how many people’s lives will be worth remembering, except as a ‘case study’ for reflection by some form of academic or pseudo-academic psychology? Piers Torday in his review has a particular delicious tongue-in-cheek version of this tendency, wherein the author gives full flow to a penchant for extended metaphor based on the death of mock-tragic fledgling birds, whose overweening youthful ambitions are their downfall:

… like so much in Tomlin’s ‘rackety’ life, fledgling promise was never given a chance to fully take flight, for he was no mere bird-lurer but a man of protean sexual abilities, driven by erotomania. The writer Gerald Brenan described him as ‘ambisexual’ who ‘went to bed with anyone and everyone, often merely for the sake of company’. He was a man not given to lengthy self-reflection and wrote to one of his girlfriends, ‘I believe “making love” depends on sense of superiority over the object of your desire.’ In a coda here, the authors suggest that Tomlin was a particular Jungian type, the puer aeternus, or boy who never grows up – a priapic Peter Pan.[3]

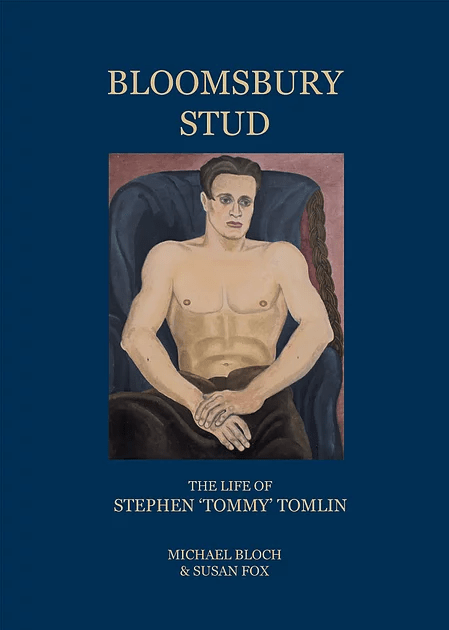

I think public writers sometimes sacrifice their humanity and the value system in which lives are understood by and with empathy when they write in the public domain, particular when summarising whole ‘lives’. Take the vocabulary here. Rackety though (used in ‘scare quotes’ but in order to show what modification of intent is never clear) feels to be highly characteristic of the way literary critical discourse takes a superior stance over its subjects, mired in the difficulties and guided by the scars as well as the aspirations of their life forces. It is such an elitist term meant to single out those without sufficient social grace – ‘loud’ in the worst possible way implied by class and status based distinctions. It is used of people who behave as if they deserve more attention than they get. And for Torday, Tomlin seems to be an example of ‘something wrong’ in a life, using Virginia Woolf’s highbrow summation. The final effect is, based probably more on a pretension to literary wit and wordplay than strong homophobic values (I hope) to end his piece with a flashy generalisation that implies more about the necessary attitude to the sexual lives of those in the past than it may have intended. He says of the book (see above for illustration of the front cover): ‘its erotic cover portrait might wink at a gay romp of a life, but this romp, it turns out, was not so very gay after all’.[4]

Never have the ‘pretensions’ of the use of a word like ‘gay’ to describe a ‘lifestyle’ been more pricked. One almost feels like one is returning to those stale debates about how a perfectly innocent English word for lightly worn happiness has been corrupted, a statement so oft given once people forgot that it was neither true nor how the meaning of words change. It raises for me, and did after the review caused me to buy a copy of this book from the website, the issue of the categorising of sexuality in the lives of artists, whether ‘failed’ or successful, and this is particularly pertinent when such categories are used to describe ‘failure’. And Tomlin attracted many sexual category descriptions from Brenan’s ‘ambisexual’ to more lasting ones like ‘gay’ or ‘bisexual’. Even more pertinent the launch of these authors into what is falsely called ‘critical psychology’ (I mean the system of Carl Jung) and their decision to label Tomlin a puer aeternus. And this choice of terms from Jung’s theories of male narcissism was once typical in ‘explaining’ the lives not only of ‘homosexuals’, ‘non-prescribed drug addicts’ or alcoholics. It offers as far as I can see no explanation at all – as with so many psychiatric labels.

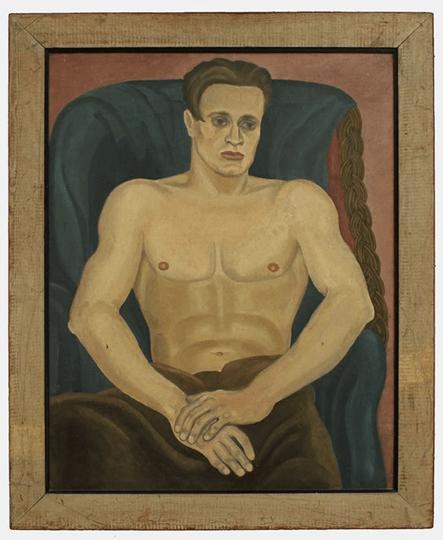

Even if we take the effects of the cover portrait, we can see how sexuality is translated by outworn assumptions and stereotypes. For a start there is no ‘wink’ in this portrait, just outright directness of gaze on the viewer. It is a gaze that seems to query the viewer in my response to it, asking them to question their response whether it be to visual beauty or erotic stimulation somewhat sadly. And the eroticism here, after all, is not something inside the person and personality of Tomlin but more justly of the painter John Banting, as the biographers make clear in their speculations between painter and model, based on the evidence of Edward Sackville-West (Eddy), who also loved both Banting and Tomlin.

Eddy mentions [Banting] (along with Tommy) in a list of his lovers; and that Banting’s relations with Tommy also went beyond those of artist and sitter is suggested by a letter he wrote to Bunny Garnett from the South of France during the 1930s, alluding to ‘a short interlude with a tough which ended with his robbing me … he had a certain something of Tommy about him.[5]

Precisely these networks of desire between men of very different kinds is what Torday means by the ‘gay romp’ we were promised by the painting and, perhaps, points to the tawdriness that the word ‘gay’ hides. But I find this neither tawdry nor a romp. What we have is a picture of desire in the field of very real human relations, where mistakes are made about the value of certain ‘relationships’, as indeed the meaning of what we call ‘values’ in relationships. I don’t think the authors of the book get this wrong. Largely they stand outside their subject and whilst they may not evaluate ‘Tommy’, they certainly allow us empathy for him as a person like ourselves. The mistake, if it is one, is the need of our culture to believe that people, other than themselves, can be judged solely against the qualities of labels, whether these are psychiatric or from everyday usage or folklore knowledge.

I think the idea of the Jungian ‘type’ of the puer aeternus is, like in my opinion much of Jung, overestimated in its usefulness in the analysis of the aetiology of sexual identities in this book.[6] Given that we all may rely pragmatically on under-theorised concepts sometimes in our lives the authors of this book can take this too far. Thus, when the authors recount David ‘Bunny’ Garnett’s comment in his diary that Tommy treated his mother, as he led her to a taxi, ‘as tenderly as a lover’, there is no excuse for the parenthetical authorial comment: ‘(This suggests that Tommy suffered from an Oedipus complex)’.[7] Sometimes I hope that there will be a day when even researchers and writers in the history of art (academic or otherwise), who tend to hang on to antique cognitions longer than most, will stop seeing a need to explain queer artists in terms of half-baked, badly applied and ill-understood psychological tropes. But, though I bristled at these poorly judged excursions into psychodynamic explanations of Tomlin’s sexual ontology, I think they are forgivable given their obvious naiveté and the lightness with which those concepts are worked into the overall picture of Tomlin the authors otherwise give. What appeals in contrast in the authors’ account of Tomlin’s creative and sexual development and the interaction between these features of the man are the close accounts of his experience, such as his fascination with the erotic shaping in stone of the figure of the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley in Edward Onslow Ford’s (named Henry rather than Edward by these authors) Shelley memorial at University College Oxford:

From the moment he arrived [at New College Oxford at the age of 17 in January 1919] , Tommy seems to have been miserably unhappy. On the other hand he was morbidly fascinated by the Shelley Memorial – an enormous homoerotic recumbent nude statue of the drowned poet …, which nearby University College had accepted from the Shelley family in 1893 (with some misgivings, not only on account of its sexually suggestive nature but also because Shelley had been expelled from that college for his atheistic views): Tommy (we are told) would stare at it for hours.[8]

Despite the insupportably long sentence in the paragraph above which gives me hope as a writer myself, this is worth much more than all of the reductive psychoanalytic interpretations otherwise provided in the book in moving us nearer to the longing which made Tomlin’s best art and of his embodied life in the image of a tragically needy and very appetitive sexual being. Ecstatic, androgynous and deeply pained vulnerability is a million miles from the picture we otherwise get of Tomlin’s voracious sexuality but sometimes the rush to contrary subject positions in life tell truths that introjected social aspirations wish to hide for many reasons, not least the credibility of one’s own adoption of a masculine stereotype, which poor ‘Tom-Tit’, who was continually throughout his life and in this biography’s policy to use this nickname without flinching and very frequently diminished by the childish sobriquet, ‘Tommy’. I will return to the importance of vulnerability and defences against its evidence as a means of supporting ideologies of masculinity later in this piece.

Tomlin’s queerness is far too easily reduced into the notion of ‘repressed homosexuality’ or even by the term ‘bisexual’, which too easily reproduces the binary assumptions of heteronormativity. His fascination is with the body and, although this is easily read as a fascination as a fascination with the reflected effect of his own beautiful body on others and thus to a kind of ‘narcissism’, I really do think there is more complexity than that needed in the picture. That reading is of course very properly prompted by his wife, Julia’s statement, as she struggled and sometimes gave up and absconded from his appetite for others to show their appetite for him, that: ‘Tommy’s daemon insisted that not only with their souls but also with their bodies everyone must him worship’.[9]

Even in Banting’s portrait, this body invites our gaze in worship and lust and is, without any need to make the organ visible, intensely phallic – the geometry of Tomlin’s musculature and his arms drives us down, as to the apex of an inverted triangle, to his folds of his clothing around his groin, which almost sits on the edge of the bottom of the picture frame. That this embodies Banting’s desire as much as anything in Tomlin seems obvious to me, not least because the Tomlin painted also defects from any appeal to the eyes of his viewers with an off-centre gaze and the head, and therefore eyes slightly tilted to the viewer’s left. Narcissism alone will not suffice to explain this just as images are never able, and may be entirely incognisant, to articulate all the contradictory emotions that explain their power, not least the (temporary at the very least for men in a patriarchal society) the vulnerabilities exposure brings.

The more this biography quotes people quoting Tomlin’s verbal behaviour and prompts to others to share his sexual fascinations, the more an image of intensely self-aware male power do we get, and the more sex is reduced to something almost technical and merely functional in its appeal. This goes as much for the penchant for acronyms like CT (for ‘c—teaser’), used to those who do not play the sexual game fully and experience it in mainly in fulfilling and draining Tomlin’s phallic energies, even in very public situations.

In June 1930 [Julia] mentions a visit from a male model described by the initials ‘C.T.’. This is presumably the youth concerning whom an anecdote circulated among their friends which Cyril Connolly repeats in his journal:

‘You can’t do this here – not with your wife in the room,’ said young man to Tommy who was assaulting him. Tommy looked at him insanely – ‘Cockteaser!’ and continued.

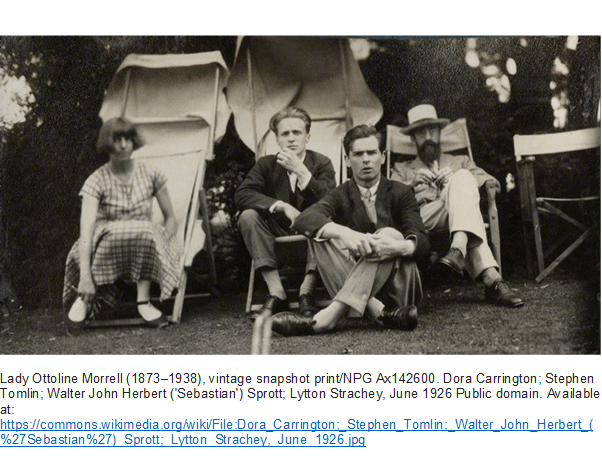

Likewise the acronym ‘P.A.’ (for ‘penetration anale’ presumably in the belief that the French terminology for ‘anal penetration’ sounded more Bloomsbury) in a letter in which Carrington repeats to Tommy’s wife, Julia, more salacious evidence of Tommy’s continuing aggressive sexual behaviour. Of course, the story is based on a lot of assumptions. Carrington writes of an operation to remove a ‘sentinel pile’ endured by Sebastian Sprott – the Cambridge psychologist W.J.H. Sprott – both appear with Tomlin in the photograph below by Lady Ottoline Morrell – because, she asserts, he has been led into this sexual practice by Tomlin: ‘I told Tommy what his great creed ‘of P.A. & nothing but P.A.’ had led poor Seb into. But he merely rubbed his hands at getting another convert’.[10]

Of course, we misread this if we see it as other than a sample of the salacious in-group talk that characterised the margins of the Bloomsbury Set and the London literati. Presumably, Carrington had very little to learn about sodomy after a long relationship with Lytton Strachey who, like Virginia Woolf, identified gay men as ‘Buggers’. We will misunderstand these exchanges, intended as witty and not at all as merely vindictive (though they could have that edge) if we do not see it in the context of open discussion about sexual practices in the Bloomsbury Group. For instance, Strachey uses the same term ‘conversion’ to John Maynard Keynes in order to describe how and why responses to sodomy need to change and why they will only do so with difficulty and patience:

‘Our greatest stumbling block is our horror of half-measures. We can’t be content with telling the truth – we must tell the whole truth, and the whole truth is the Devil. It’s madness of us to dream of making dowagers understand that feelings are good, when we say in the same breath that the best ones are Sodomitical. [However]… our time will come about 100 years hence and everyone will be converted.’[11]

As Anne Taddeo says, in citing this, Strachey was not intending to talk here about dowagers converting to the practice of sodomy but to a belief in its potential for beauty and meaning in a relationship that chooses it as a form of mutual expression. I think Bloch and Fox may miss this subcultural finesse in merely using this as an illustration of the psychoanalyst wife of James (Freud’s English translator), Alix Strachey’s assertion of Tommy’s ‘scorn for the other and contempt for himself and public showing off and sadism and crudeness’.[12] They might have taken into account reasons why Carrington and Eddy Sackville-West, to whom Alix Strachey was writing, might want to see the present day Tomlin as a lesser man sexually than he was when they were involved with him.

There are lots of reasons why Tomlin attracted opprobrium because of his lack of sexual boundaries (and boundaries based on sustaining longer-term relationships) and many of these do not lend themselves to an empathetic approach to the man himself. However, a biographer should, and I think Bloch and Fox do to a large extent, away from such motives. They nevertheless struggle, perhaps we all would with Tommy’s asserted beliefs about the relationship of love and hierarchies of power, which he repeated twice to Henrietta Bingham, whom the biographers believe was the only person he ever really loved, and therefore wrongly characterised in Piers Torday’s review (quoted above) as just ‘one of his girlfriends’.:

‘If only I could cultivate that healthy contempt for you that becomes the amorous male! But you have robbed me of it …’.

‘I believe “making love” depends on a sense of superiority over the object of desire, but “being in love” on a sense of inferiority to it. So that once you are “in love” you cannot “make love”, & so cannot make the other party love you’.[13]

These distinctions between love as sex and as an emotional state are common binaries used in everyday life that are based entirely on semantics of course. We need not call sex ‘making love’ nor characterise the emotional state of love as a passive and emotional state. Yet it is on flimsy evidence like this that biographers, and earnest early English psychoanalysts like Dr Edward Glover, diagnoses ‘dual personality’, often in another acronym D.P. to describe Tomlin’s character.[14] They point to the controlling nature of his sexual being. which the biographers also call ‘imposing his will’, in the ‘Hyde’ of his ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ personality. There is no doubt, of course, that mental ill-health severely impacted on his life and relationships but I also feel that much in his personality illustrates as much the ideological contradictions of social and emotional life under conditions of an individualism that was fostered beyond notions of sustainable and shared community, like that of Tomlin and which subsists still. As I read about his love-life I notice not only ‘guerrilla tactics’ his friends delighted in unearthing in what they see as his predatory behaviour but also their equal dislike to the fact that many people seemed drawn to the abject servitude that loving Tommy could sometimes mean.

What speaks to me in Stephen Tomlin and some other men I know is the contradiction deep in the emotional life of individualistic cultures between sustaining what is virtually universally treated as a myth of loving as shared fulfilment and the reality of unequal power within and between human relationships and groups. And the victim here is the vulnerability which remains at the core of human ontology and which makes us a social animal at base. Biographers and others struggle with how to place the extreme vulnerability of Tomlin at moments of his life, and perhaps in more than moments. Was this part of the Jekyll or the Hyde of his personality? In fact it is a factor that shows the nonsense of such binary diagnoses and which led psychiatry from concepts of dual personality to its modern pluralist version dissociative identity disorder. But my point is not here about the nonsensical elaboration of binaries – the first recourse of a culture obsessed by notions of illusory individualism – and there translation into multiple fragments of self. It is about the fact that expression of emotion and meaning is only about coherence if the culture insists it must be, without addressing the problem of a world fractured by inconsistency, inequality of power and experience of power that cloaks itself in ideologies of reason and assumed coherent wholeness.

Tomlin never it seems to me quite ever learned to love his vulnerable self and found it hard therefore to love or respect vulnerability in others. Personally, I find this a common issue in social life. Tomlin’s Oxford friend, Roy Harrod, the biographer of Keynes and cited fully by this book, spoke of his ‘“horrible despair and anguish”’ that ‘made him feel “personally guilty of all the sufferings taking place in the world”’.[15] This is a powerful broth in which positive, negative and a universe of contradictory feelings mix and which mean that Jekyll, Hyde, longing for justice and awareness of injustice constantly masking itself never quite cohere, except in those the world makes through luck, subterfuge or sheer negligence of the feelings of others in the joy of serving oneself oblivious to the any need for justice, morality or decency in our relational ontology. In brief the life of Tomlin is to me a symptom of a sick society which sometimes shows society its own ugly face beneath the mask. Oscar Wilde expressed it thus: ‘“The nineteenth century dislike of Realism is the rage of Caliban seeing his own face in a glass. / The nineteenth century dislike of Romanticism is the rage of Caliban not seeing his own face in a glass.”.[16] The moral outrage around Tomlin strikes me very much thus. Harrod is cited further as saying:

‘it would seem that so much physical force went into the understanding of others … that there was no energy left for building up some kind of idea of his own life; when it came to that, he found himself stripped of all vitality, a poor, dejected creature, a broken reed’.[17]

I love this biography because it tries to be fair to the beauty of some of Tomlin’s achieved relationships. While it is possible to read his only successful relationship, to a working class Wolverhampton man he knew as ‘H’, as a sign of his love of acknowledged ‘inferiors’, H. Williams’ words to Tomlin never seem merely those of a man disempowered and employ much irony about his ‘humble’ status.[18] His art is at its best, and here I follow the biographers slavishly in agreement, when it recaptures the seeking identifications with which he stared as a student at the Shelley Memorial. For instance, he was at his best in capturing almost literally out of time, Virginia Woolf’s despair and the terrible reflecting multiplicity of her own identities in his bust of her, not least her controlling and imperious dismissal of weakness like that she refused to want to see (whilst keeping on doing so) in herself. Woolf’s cited response to sitting for Tommy is as much the rage of Caliban as anything else in this book witnesses, who remain the main ‘evidence’ for what Tomlin was like.[19] She ‘took a shudder at the impact of his neurotic clinging persistency’ and it speaks in the bust itself and destroyed Tomlin as an artist whilst it was the acme of his achievement.

But Tomlin could also write out some of the absurdity that he was aware of in the sexual ‘dance’ and the omnipresence of power within it, in his 1933 poem ‘The Sluggard’s Quadrille: By the lobster’. Although clearly owing everything to Lewis Carroll’s framework fantasy, its injunction, “Will you walk a little straighter?” said a clergyman I knew’ will be recognised with both humour and some of the fear of the authority that queer people always introject, and usually loudly dispute having done so.[20]Its fear of night seems also a fear of the sexual drive as if it were a thing other than oneself, so much does it betray its object. One verse is surely a response to Oscar Wilde’s summation of a life (in De Profundis of 1913) – who might himself too have been referring to Alice Adventures in Wonderland, chapter X – lived amongst available youths and rent boys and the instability of desire twisted by oppressive secrecy, hiding and having to brand desire a vulnerability and yet deny that very vulnerability: ‘It was like feasting with panthers. The danger was half the excitement’.

Then in the garden of my dreams,

Where the dark Panther growls and rumbles,

The Knife is waved, the Pie-crust crumbles,

Athene’s bird protests and screams.

I am the Owl. I am the Pie.

The spoon, the dish, the Panther – I.

And ere dawn whitens in the East

I celebrate the dismal feast.[21]

His is a life about much we know so little and to be fair this is what these biographers say with so much integrity. Even when I disagree with interpretation, they never try to make it the interpretation of Tomlin’s life and that matters in biography.

Yours Steve

[1] From Stanza III The Sluggard’s Quadrille By The Lobster (published 20 May 1933 in New Statesman and Nation), reprinted as Appendix III (page 230) in Bloch & Fox, op.cit.: 222 – 231.

[2] For Tom-Tit see Bloch & Fox (2020: 20)

[3] Piers Torday (2021:9) ‘He Slept His Way to the Bottom’ in Literary Review (Issue 494, March 2021) p. 9.

[4] ibid: 9

[5] Bloch and Fox (2020: 100).

[6] ibid: 211ff.

[7] ibid: 47

[8] ibid: 29

[9] ibid: 14

[10] Carrington Letter to Julia Strachey, now Tomlin, in April 1928 cited ibid: 155.

[11] Cited Taddeo, Julie Anne. “Plato’s Apostles: Edwardian Cambridge and the ‘New Style of Love.’” Journal of the History of Sexuality, vol. 8, no. 2, 1997, pp. 196–228. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3704216. Accessed 22 Apr. 2021. The page containing this citation is visible without further needs of access rights (via an academic institution) at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3704216?seq=1

[12] Alix Strachey to Eddy Sackville-West in October 1928 from the Sackville Papers in the British Library cited ibid: 154f.

[13] From Tomlin’s letters to Henrietta Bingham, 24 May 1923 & 26 March 1923 respectively cited ibid: 67.

[14] ibid: 81.

[15] ibid: 32

[16] ‘Preface’ to Oscar Wilde The Picture of Dorian Gray (Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, 2008) ISBN 9780199535989. Edited with an introduction and notes by Joseph Bristow. Based on the 1891 book edition.

[17] cited Bloch & Fox, op.cit.: 33

[18] ibid: 172

[19] ibid: 170

[20] From Stanza III The Sluggard’s Quadrille By The Lobster (published 20 May 1933 in New Statesman and Nation), reprinted as Appendix III (page 230) in ibid.: 222 – 231.

[21] From Stanza 1 of the same in ibid: 226

One thought on “‘ “Will you walk a little straighter?” said a clergyman I knew’.[1]: On Stephen “Tommy” Tomlin and why sexual categories can be so confusing when used to summarise a life! Reflecting on : ‘The Bloomsbury Stud: The Life of Stephen ‘Tommy’ Tomlin’ by Michael Bloch & Susan Fox (2020).”