When the Sea Pinks fade will white boys fear the heat of the Sun. Identity Markers, and Arrested Male Development: reflecting on the Cicely Robinson’s [Ed.] (2021) Henry Scott Tuke. New Haven, CT., Yale University Press (in association with the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art).

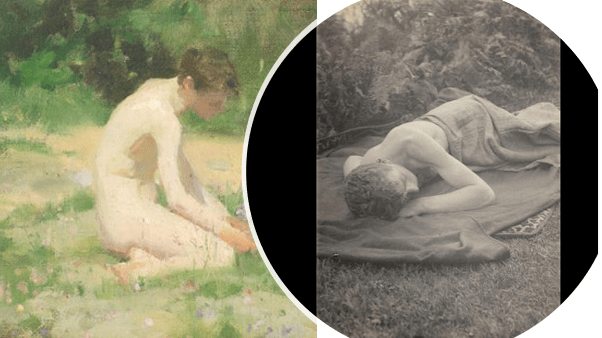

Images of Georgie Fouracre, aged 14. Cropped & Collaged images from HENRY SCOTT TUKE, RA, RWS (BRITISH, 1858-1929), ‘Sea-pinks’, oil on canvas board, 14.5 x 24cm.[1] and Photograph of George Fouracre lying on a rug posed for the figure in ‘The Coming of the Day’ (1901), Black and white print, 165 × 120 mm, Photographer unknown.

These personal reflections on sexual development or its absence go somewhat at a tangent to even the best work on Henry Scott Tuke. I attempt to look at the confused relationship in Western colonial and postcolonial cultures in lived and recorded history respectively between discourses of paedophilia, race, queer sexualities and the male nude as art object. It is a subject often avoided (especially the discussion of paedophilia) but in doing so, we might fail to address complexities in long-lived ideas of sexual development and its relationship to relations of power between social groups as a feature of all sexual relationships, queer or otherwise, which fracture liberal thinking. It touches on some issues in the relationships of artists and models explored in an earlier blog on Singer Sargent (follow link).

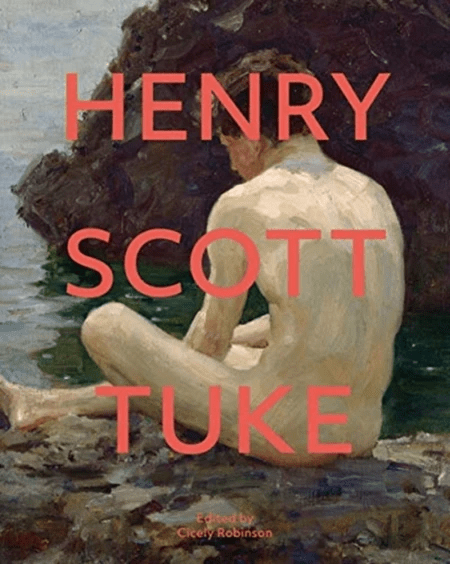

These personal reflections on male development in liberal Western societies could not happen without Cicely Robinson’s ground-breaking collection of essays on Tuke. This new book contains work in the history of art, which appears in its finest examples of a socially responsive history of art. As homage, here is the front cover of the book with its iconic picture of reflective avoidance: The picture of adolescence as a turning away, and looking down into danger is an important icon of arrested development of the body, sensation and interpersonal development to which I will keep returning, helped by Robinson and colleagues and especially Michael Hatt’s brilliant essay, ‘Tuke’s queer lyric’.[2]

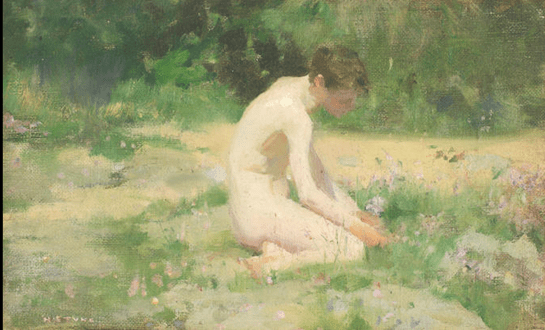

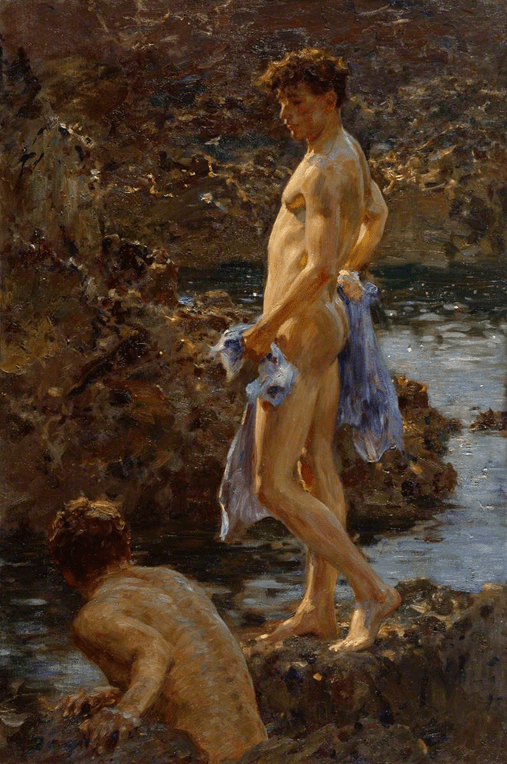

I want to start by concentrating on images of his young model, Georgie Fouracre (the son of his landlady in his Cornish lodgings), at the age of 14 or so (see note 1) that is not dealt with in this book in contrast to a more famous one, To The Morning Sun of 1904 that is. The latter is discussed by Nicholas Tromans in a fascinating study of the influence that the psychological research interests (known more accurately in the language of the period as ‘alienist’) based on the work of Jean-Martin Charcot, of Tuke’s father, Dr. Daniel Hack Tuke.[3] Tromans concentrates on the latter painting which he sees as related to the more obvious paganism of Fouracre’s appearance in To The Coming Day of 1901, of which the Tate possesses a photograph of Fouracre in preparation thereof. Fouracre, aged 20 or so in 1904, lacks the obvious vulnerability of the earlier painting collaged in my opening (follow link for complete image from Bonhams’ sale) but Tromans is assertive about the fact that these pictures of a young man hide the exposure to environmental and weather conditions and of holding painful body positions that is in part their hidden subject as well as technique.

There are also memories of the somnambulism and hypnosis that so preoccupied Tuke’s father and their friend Charcot. From those dramatic demonstrations, Tuke may have retained some notion of the controlling another’s body, of making it submit to one’s will and giving that body the power to maintain postures, or attitudes, that would have been hard to maintain voluntarily.[4]

Without saying Tuke hypnotised his young male models, Tromans points out that the consequences on our understanding of power differentials can be read in the hidden dramas of somatic experience that the practice of nude painting en plein air involves, hidden at the very moment they are revealed because of the difference of temporal duration of spontaneous physical gestures and attitudes and the long time and endurance needed to model them for a painting of that short moment. In my own view, though the link to the alienist techniques of Charcot and others is enthralling; both reflect that technique and that the practice of using models in Western painting are built out of prevailing and strong power relations of class, race, status, income, gender, age and numerous other differentials.

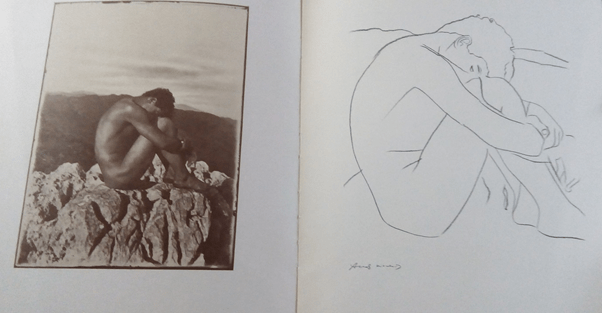

My point about Fouracre relates the exposure of the young and naked Fouracre to the power of the gaze but it will concentrate in part on the interest in his whiteness. This colouring of the skin is in part a product of exposure to strong morning light but I feel that it is built on the same racial contradiction as are John Singer Sargent’s nude watercolours, painted whilst he was a First World War Artist, of Tommies Bathing. I touch on this only lightly in an earlier blog. My suspicion is that the Occidental taste for the male nude can be clarified by the extreme example of the photography, sometimes called art and sometimes pornography, of William van Gloeden. In order to follow up this idea I consulted an essay by Roland Barthes in a catalogue of the exhibition at the 1978 21st Festival of the Two Worlds, which featured responses to the photographs by Joseph Beuys, Michelangelo Pistoletto and Andy Warhol. The von Gloeden photographs in this exhibition focus on post (and pre-) pubertal boys (and some men), all nude or dressed in the appearance of classical robes and headdress (although sometimes these boys were dressed to appear as girls or as hermaphrodites) and veer from the sentimental to the exhibitionist, often focusing on the phallic equipment of his boys – a focus Warhol’s drawing emphasise by close-up attention but are also a pastiche of pagan ritual religiosity. The example below (not in the catalogue) still gives a very clear idea of their nature. The eyes of the model engage the viewer (and indeed a finger points towards them) but rarely invites closer or sensual contact. They nevertheless always implicate the viewer in the visual appreciation of what is given up to the gaze, even that which I occlude in this cropped version for the sake of those offended by the sight of male genitalia.

Wilhelm von Gloeden (1856-1931). [cropped version – see link for actual image] A naked boy wearing a flower crown and carrying an amphora. Catalogue number: 1039. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gloeden,_Wilhelm_von_(1856-1931)_-_n._1039_-_da_-_Amore_e_arte,_p._92.jpg

Barthes however points out something else; that the photographic subjects address the reader in a number of sometime contradictory languages that rub against each other in order to complicate the nature of the image’s appeal.

Ces contradictions, ce sont des “hétérologies”, des frottements de langages divers, opposes. Par exemple: von Gloeden prend le code de l’Antiquité, le surcharge, l’affiche pessamment (éphèbes, pâtres, lierres, palmes, oliviers, pampers, tuniques, colonnes, stèles), mais (première distorsion), de l’Antiquité il mélange les signes, combine la Grèce végétale, la statuaire romaine et le “nu antique” venu des Ecoles de Beaux-Arts: sans aucune ironie, semble-t-il, il prend la plus éculée des legends pour de l’argent comptant. Mais ce n’est pas tout: l’Antiquité ainsi affichée (et par inference l’amour des garçons ainsi postulé), il la people de corps africains. (translation in footnote).[5]

This is about more than camp playfulness or the disguises under which desire conceals and simultaneously reveals itself, it is about the pain as well as the pleasure of frottage, it validates the power involved in taking that pleasure from persons less powerful than ourselves, children by adults and the African body by the European colonialist. It is in this context I think that painters become interested in the purity of white in flesh before it has been coloured by the sun, whilst it dares exposure to that sun. Now whiteness has many meanings in colonial and postcolonial literature – most of these are explored in Herman Melville’s novel of 1851, Moby Dick. But for our purposes let’s limit them to the ways in which they represent non-engagement in the conflicting and muddy contradictions of living, either in ideals of innocence, and its temporal pre-worldly moment in time, or the pallor of death. In both instances colour, whether from the internal dynamics of the blood or the permanent or temporary colouring of the skin are seen as absent. Let’s look again at 14-years-old Georgie Fouracre in the full image of Sea Pinks:

It is commonplace to speak of the interest of Tuke in the effects of natural sunlight in different temporal contexts, on flesh, and here whiteness is seen (as in Sargent’s two watercolours of Tommies Bathing), as an effect of the interaction of the colour of the perceived ‘object’ and the light source. It is for this reason that Tuke is sometimes identified as an ‘Impressionist’, but Tuke is surely here also recording not merely impressions to the visual sense but also both invoking and expressing other sensual, cognitive and performative material that of necessity involves elements of narrative and narrative (that is to say ineluctably temporal) symbolism. This is why I believe that Tuke’s young boys never, as Von Gloeden’s boys definitely do on the whole, engage our eyes by ‘invitation’. I say ‘on the whole’ because we will look at an exception later. Moreover, strictly speaking, any ‘invitation’ in the boy’s eyes (as in Picasso’s abused female models, is anyway a trick of the use of models by artists in visual media to attribute the qualities of the image’s creator and its medium to the model him or herself, and thus evade some of the responsibility for the meanings, evoked sensations and performatives in the image. Tuke’s young boys characteristically look downward or to the view behind them rather than the viewer, at least directly. Georgie is concentrating here on the sea pink plants.

Flowers that bloom in spring and early summer are likely to fit nicely into the associations of renewal being also associated to morning light and youth, but their colour also captures that absence of self-conscious blush in Georgie that might be used to betoken self-consciousness and / or guilt at his own nudity. The relation between the pinks and Georgie is however clearly proprietary. Georgie is, in some way, if not in the process of picking these flowers, though he may be – it is a minor but significant tension in the moment, collecting their values into himself both as a symbol of flowering not yet begun, at least in the boy, and of a rite (and right) of passage, alongside other rites of spring and morning. It is all so precarious. Hence the complexity of Georgie’s skin, especially those flecks and painterly daubs of pure white that capture the effect of sun on bare white flesh and the need for Tuke to emphasise quite bleakly contrasts of external light and the shade of elements of skin that form the carapace of an interior (Georgie’s underside). And perhaps, only then you notice the difference between the tanned hands, used to sunlight exposure and previously unbared flesh. I’d insist, for my own purposes as a viewer, that we cannot imagine Georgie’s sustained exposure to the sun from this picture. That would be to emphasise too much (as is invited) in von Gloeden’s boys, the sense of his willing participation in public and daytime exhibition. Exhibition in other paintings is a mere by-product of the capture of their other in play or preparation of adult maritime life, as in his bathing pictures. But, in the early nude pictures – and quite unlike the tanned tars of his sometimes simultaneously exhibited clothed ‘Victorian narrative’ pictures of mariners discussed in this book by Mary O’Neill (even boy models like Jack Rowling enacting mariners) like the very staged All Hands To the Pumps of 1888-9 (follow link to see this painting).[6]

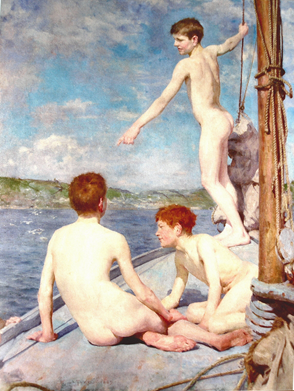

Bathers 1888 – 9, oil on canvas, 116.8 cm (45.9 in); Width: 86.3 cm (33.9 in), Leeds Art Gallery, Blue pencil.svg wikidata:Q6515835, In Robinson op.cit’: 67 Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tuke,_Henry_Scott_(1858%E2%80%931929),_%22The_Bathers%22.jpg

Tuke does paint tanned boys, clearly exposed to the sun over longer periods but I sense (but I am not knowledgeable enough to assert) only later in his career and as a response to Central European ideas and a new model. The latter, Nicola Lucciani, saw himself as a ‘professional’, Nicholas Stephenson implies but never quite says. Of course, we know so little of these young men’s actual thoughts. Lucciani was imported into his home in 1911 from central Europe.[7] In the 1914 Bathing Group Nicola is not gazing at his viewer through the picture frame but the viewer’s gaze is directed from the subject boy near Nicola’s feet up and over this superb (almost as if classically sculpted in contrapposto) tanned body.

Henry Scott Tuke (1858–1929) A Bathing Group 1914, in Robinson, op. cit.: 86. Oil on canvas, Height: 90.2 cm (35.5 in); Width: 59.7 cm (23.5 in), Royal Academy of Arts Blue pencil.svg wikidata:Q270920 03/258. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Henry_Scott_Tuke_-_A_Bathing_Group_(1914).jpg

There is an enormous difference, other than merely in age, in the way the body supplied by Nicola Lucciani is conceived and executed in paint from the white-fleshed examples above. The body here has experienced time and sun (and can perhaps have been imagined to have experienced the attentions of even Apollo himself). In another painting where Lucciani appears as the Faun of 1914 (see link for painting reproduction), his gaze is directed at the viewer and appears somewhat proudly knowing. The frankness of the gaze allows the viewer a more privatised personal access to the body, if only through imagination of him as a mythical creature. Nevertheless this creature ‘knows’ he that that about him that will be ‘much admired’ as was Lucciani for his ‘handsome Italian features, curly dark hair and tanned, olive skin’.[8] We are much nearer here to the case of van Gloeden, though the artistry is, of course, arguably so much the greater. The mise en scène is clearly designed to conceal, and thus paradoxically to reveal, as Marlowe put it of the masques enjoyed by his King Edward II, ‘the parts that men delight to see’.[9]

However the point I need to stress is that skin colour is a troubling signifier in Tuke in that it, without even the enforced cooperation of the model’s gaze, it creates an aesthetic invitation to merely look at the way in which the painters markings have constituted (and literally made) the body by subtle manual strokes of the brush and bold swathes of applied colouring both of the unevenness’s in the tanning of the body integrated into the effects of a more complex lighting that is clearly not that of the morning sun. Of course, when I call it troubling, I mean only that it evokes something more than just visual awe. In order to end on this merely suggestive note, which I think evokes notions of race and ethnicity (and hence power relationships) as well as the more painterly issues of the use of colours and tones.

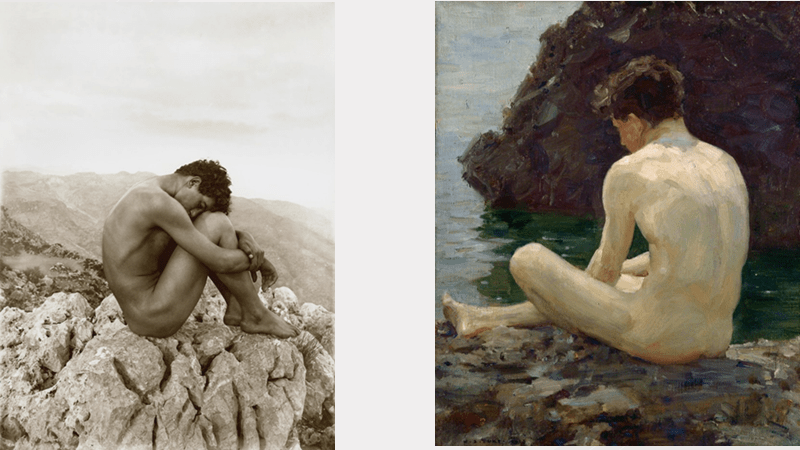

Stephenson in a chapter that looks at the tradition of using adolescent boys as a subject discusses von Gloeden’s Kain by comparing its effect to three examples of Tuke’s adolescent nude males but focuses strangely enough on July Sun and traces both back to Jean-Hippolyte Flaudrin’s Nude Sitting by the Sea. Figure Study 1835-6 (follow the link for painting). Whilst conceding the differences, obvious to my eye at least, between the attitude and pose of the model in Tuke’s painting and those past models, Stephenson insists that it demonstrates:

… a familiarity with its compositional codings, as recycled and disseminated [in the tradition]. Moreover, the close-up study of the self-absorbed youth and the sense of studied introspection in July Sun in particular, produces a kind of formal emptiness that encouraged the possibility of homoerotic re-inscriptions by homosexual male viewers. However, July Sun … [is] not set in the Mediterranean, but in Cornwall, and … [the] boy’s skin tone is decidedly pale.[some italics indicate the rephrasing of the syntax of sentences to make them coherent with the reading of one painting only].[10]

A lot is here inferred from an assumption about ‘familiarity with’ the ‘compositional codings’ from past works that show only a superficial similarity. They are both of nude male youths by the sea who may be inferred to be reflecting inwardly in short. The pose is otherwise entirely different, showing codings that do not lend themselves to drawing the analogy here. Tuke’s boy sits with total disregard to the aesthetics of the visual forms he takes and this is not just because we see him from behind. It is also because his legs deliberately fall out of any enclosing rhythm created by arching of the back. Tuke’s young man sits with an ungainly pose rather than a studied one that may be as much about the boy having his attention drawn to a momentary sensation in his body – perhaps the knee or lower leg. This might explain why he holds one leg, if he is holding it – the painter on purpose as it were occluding these gestures and performative actions so they can only be guessed at as possibilities of what the boy is ‘doing’- across the foot of his other leg.

This boy is not fully closed on his body as is Kain and is not therefor, like Kain drawing the viewers attention to the body as a whole. What is powerful in Tuke is the attention to parts of the body rather than a merely formal composition. And there is more weight to Stephenson’s contrast of both setting and skin colouring and tone than he allows I believe. Kain is a mythologised being, the boy in July sun is very definitely not and hence can be read with much more open potential to the meanings of behaviour, gesture and the content of cognition that can the Flaudrin trope. Von Gloeden wants us to see the contrast between the scarred bare rock and the smooth accessibility of a boy’s skin that shines through its skin coloration like a patina, as in all the finest of objet d’art. This isn’t true of Tuke where the textures that compose the boy’s hair and the rock in the background constantly draw attention to similarities about how each are made and differentiated in the strokes of the artist’s brush or mark-making by other implements. Tuke’s boy is in part a growth of his world, von Gloeden’s boy has been placed in his world in a position advantageous to our sightlines or appreciation of the enclosure of insides by a single outside gesture – the line of an arc.

In my view Stephenson tries too hard here to suggest that the painting is a coded secret for a specialised ‘homosexual’ audience. This feels to me a means of grossly oversimplifying the nature of sexual desire such that it fits the more the more perfectly the model of the free economy of sexual desire led by powerful and less powerful forms of demand. It is true that these images have appealed to ‘homosexual audiences’ but the nature of that appeal may not be as simply understood as any simply heteronormative hegemony in the social understanding of sexuality would imply. It would seem to me that von Gloeden does considerably simplify Flaudrin’s icon of the reflective seaside ephebe, but that oversimplification serves definite purposes in asserting the power of a dominant gaze – that of the Western white male whose agency as a sexual master and owner of the exotic other is facilitated socially.

It is important that the language of abstract classical beauty in the art object is used here to make otherness and colour available to the free white agent. It is a point that comes across clearly in more modern terms in Andy Warhol’s line-drawn version of Kain, where the viewer feels space for their insertion within the body space. These spaces in the von Gloeden are merely dark shadows cast in and on the aesthetic object from itself, between the graceful lines that draw the margins of the numinous other. Warhol goes the whole way in eradicating some of the lines separating self and other by further eliminating the gap between torso and leg of the model that is still evidently visible in Flaudrin’s original icon.

In July Sun, in contrast to both of those models, the boy is not offered to the gaze even of the sun itself and he is not in the position of von Gloeden’s model, a feature emphasised by Warhol, to steal a glance from a viewer directed eye. If Tuke offers his more complex nudes to the viewer’s gaze it is in a far from simple manner. Moreover the constitution of flesh, here white flesh from which the touch of sun is merely emergent, is complex – as complex as the environment from which the flesh is sometimes differentiated but also to which it is inter-related. The most beautiful effects in the colouring of flesh is on the mutual reflection of rock and the flesh of the model’s curved torso on each other, where darker colours also enter into colouration effects as well as whiter and paler ones. In my view, whereas von Gloeden makes the object available, his method is not unlike the norm nor is the ‘homosexual audience’ offered more here than other audiences, aware or unaware of the desire the object might excite from Western art from classical times. It is just that, as Barthes says, von Gloeden mixes rather radically the discourses that are allowed to rub against each other in his pictures.

And what von Gloeden chooses never to show, although I think this is not true of the Flandrin painting (which first generated this thoughtful ephebe icon), is physical vulnerability and the appearance of the inward reflection of this vulnerability in pose, gesture and somatic expressions of other kinds. Hence, though it is a simpler instance, this is the reason I wanted to think of Georgie Fouracre shivering in the morning sun as he contemplates the temporal vulnerability that is the flowering of sea pinks. And I think too of the Tate photograph of Georgie shivering under a blanket before he is called upon to pose for The Coming of the Day (see collage at the opening for an extraction from that photograph). At its simplest Tuke is more complex because his models are elegiac and essentially literary. Experience like the heat of the sun burns but it is a necessary step. It may or may not include sexual initiation but I do not think that the youths of Tuke’s nude youth paintings can be reduced to the object of paedophilic desire, whatever one’s conclusions Tuke’s own sexuality and the on the reasons for his closeness to the Uranian poets.

I often use these blogs to express my disappointment at the outcomes of the history of art, not because of its willingness to work with other disciplines but because it too often ransacks those disciplines for the purpose of its own grandiosity. This is the case with queer theory in especial. However, I feel that Michael Hatt is a proud exception to that prejudice (I am willing to admit it is that) and his essay in this book is one of the best uses of literary theory in tandem with the history of and criticism of visual art one could hope for and he ties Tuke’s responsiveness to fleeting youth , and perhaps fleeing youths, to the tradition of lyrical genres in literature. In part this allows him to explore paedophilia as a form of expression by the Uranian poets but the execrable and bathetic quality of the rhyming verse he quotes from Gambril Nicholson’s ‘The New Prospect’, may justify the term ‘queer’ but not the term ‘lyric’ in his essay title (‘Tuke’s queer lyric’).

There is a Pond of pure delight

The Paedophil adores,

Where boys undress in open sight

And bathers banish drawers.[11]

But the essay is more serious than this verse and works hard to establish how and why Tuke’s youths on the cusp of change illustrate what he calls, using the 2016 literary research of Marion Thain, and her description of;

the reconception of lyric in the late nineteenth century, a lyric is a ‘way of feeling’ as much as a formal device. In a beautiful metaphor, she describes such lyric as ‘a sentient poetic skin’, a metaphor we might bring to the surface of Tuke’s paintings[12].

This is surely intellectual sensitivity and use of scholarship that is of a very high order and even brings us back to the sensitivity of skin that reflects on discourses of race as well as class and sexuality as well as painted surfaces. It would be inappropriate for me just to repeat what he has to say of ‘whiteness’ as a concept based in sensing colour and light since it speaks beautifully for itself.[13]

But what really impresses me is that this scholarship is also responsive to genuine issues in queer lives and their developmental interactions, especially in differentiating paedophilia of the Urania sort from the diversity of sexualities and practices celebrated in the term queer. It correctly places the Uranian poets as the product of hierarchical power structures in British education. Hatt’s work is not only better scholarship than we are used to the history of art, it shows that ‘queer studies’ need not be merely a set of ideas used and appropriated as ‘theory’ by the ‘history of art’ taught in the academy (very much how it was taught on the MA in The History of Art I did but did not complete in the Open University) but discourse that is aware that it casts light on real lives – whether and both those of the now dead and those still living.

All the best

Steve

NEXT BLOG: On Stephen “Tommy Tomlin: The Bloomsbury Stud : why the term ‘bisexual’ can be so confusing! Reviewing a new book by Michael Bloch & Susan Fox.

[1] Bonhams describe it thus: ‘This exquisitely subtle, softly focused painting of a boy posing by the sea in Falmouth shows the genius of Henry Scott Tuke’s ability to capture sunlight on skin. The model is George Fouracre (1883-1947), known as Georgy, the eldest of two sons to Tuke’s housekeeper at Pennanace Cottage, Elizabeth Fouracre (1857 – 1916). Tuke lived at Pennnance from 1885 until 1929. He witnessed Georgy growing up and Tuke employed him, his brother and mother as models in his Royal Academy picture of 1890 The Message (Falmouth Art gallery). By 1897, when this work was painted, Georgy would have been 14 years old. This painting is described in Tuke’s Register of paintings as “Sea-Pinks, Georgy Fouracre stripped among sea pinks and grey stones.”’ At:https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/23917/lot/63/?category=list

[2] Hatt, M. (2021) ‘Tuke’s queer lyric’ in Cicely Robinson, op.cit.: 113 – 135

[3] Nicholas Tromans (2021) ‘Artist and alienist’ in Cicely Robinson, op.cit.: 94 – 111

[4] ibid: 104. Tromans references this assertion to vol. 2. page 603 of William James’ monumental 1891 The Principles of Psychology published by Macmillan, London.

[5] Roland Barthes (1978) ‘Preface’ in Wilhelm Von Gloeden, interventi di Joseph Beauys, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Andy Warhol Napoli, Amelio Editore. 7f. The rather wooden English translation with little of the play of Barthes’ French reads: “These contradictions are “heterologies”, frictions between different and opposed languages. For instance: von Gloeden takes the code of antiquity, he overloads it, he displays it heavily (ephebes, shepherds, ivy, palms, olive trees, vine leaves, tunics, columns, pedestals), but (first distortion) he mixes up the signs from antiquity, he combines the vegetable Greece, roman statuary and the “antique nude” derived from the Ecoles de Beaux-Arts: but it seems that he takes without any irony the most worn out of legends for cash value. And this is not all: antiquity thus displayed (and by inference the love of boys thus sponsored) is peopled with african (sic.) bodies.”

[6] Mary O’Neill ‘Nautical manoeuvres: Henry Scott Tuke and maritime Cornwall’ in Cicely Robinson, op.cit.: 35 – 53.

[7] See Andrew Stephenson (2021: 89) ‘”Par excellence the painter of youth”: Henry Scott Tuke’s adolescent male nudes.’ in Cicely Robinson, op.cit.: 74 – 93.

[8] ibid: 89.

[9] Sometime a lovely boy in Dian’s shape,/ With hair that gilds the water as it glides, / Crownets of pearl about his naked arms, /And in his sportful hands an olive tree, / To hide those parts which men delight to see, / Shall bathe him in a spring;ll.61ff. Act 1, Sc.1, Christopher Marlowe Edward the Second Available at: https://www.bartleby.com/46/1/11.html

[10] Revised from Stephenson, op.cit.: 92

[11] Cited Michael Hatt (2021:115) ‘Tuke’s queer lyric’ in Cicely Robinson, op.cit.: 112 – 133.

[12] ibid: 133

[13] ibid: 128 – 131.

One thought on “When the Sea Pinks fade will white boys fear the heat of the Sun. Identity Markers, and Arrested Male Development: reflecting on the Cicely Robinson’s [Ed.] (2021) ‘Henry Scott Tuke’.”