‘I heard the words …/ “… a ridiculous farrago supposedly linking various allegedly important moments of homosexual history of the past century. Period. …”’.[1] ‘… hardly what my shy new friend Andrew Holleran … called “Big Girl Stuff” … but lately, whenever people of importance in the gay world were mentioned, my name always seemed to come up. … I’d managed to become a sort of central switchboard for gay life in the country in all kinds of odd areas, from poetry to resorts to sex toys to fads and the latest of party places’.[2] Writing up a name in queer history: reflecting on the gay epic in a time of AIDS in Felice Picano’s (1995) Like People In History. References to 1996 first UK paperback ed. London, Abacus (Little, Brown and Company (UK)).

There is a serious point involved in the frequent occurrence of name-dropping in Like People In History since becoming a ‘name’ in queer history is itself a major theme. This might especially be the case in the example of Andrew Holleran, an invented nom de plume of Eric Garber. Using an invented name to enter the written history of queer life typifies the narrator’s, and of course Felice Picano’s, ‘shy’ writing colleague formed part of the group or ‘club’ that named itself The Violet Quill. There is a kind of joke in the use of that word, ‘shy’ (although apparently he is a shy man) to describe the act of hubris which tries to organise the random passage of time between events into a written history. Now such jokes are common: The fictional narrator’s nickname, in the mouth of his cousin the ascendant ‘Stairs’ (Alastair Dodge) is ‘Stodge’ (Roger Sansarc). Now for a writer to identify their narrator, also a writer as ‘Stodge’ is a pretty damning, even if tongue-in-cheek joke since as a metaphor it implies ‘Dull and uninspired material or work’.[3] I intend to pursue that theme much more in a later blog, which at the moment I intend to be focused upon The Lure and The Book of Lies. I will though deal with the name theme in this novel because of the intricate ways it makes characters ‘like people in history’ and not, so to speak.

The writer simultaneously pricks the balloon of his narrator’s hubris with irony (the ambiguity of writer and writer-as-narrator is the source of importance ironies and self-critique as in Dickens’ David Copperfield) but Sansarc’s/Picano’s ambition to be a noticed artist remains. In my view, this hubristic tendency matters precisely because this book talks about how fictional characters can become ‘like people in history’ in the hands of an epic writer of their times – as Achilles and Patroclus were to become in the hands of Homer. Hence, the import of Mr Logiudice, a ‘simple’ man, living in ‘Foothill Drive’ significantly.[4], This father fosters memories of his beautiful son, Matt, who has become a ‘heroic’ veteran of the Vietnam War, and a published poet, before he dies after becoming ill with AIDS (but not necessarily because of AIDS), reading as a young boy The Golden Book of Greek Myths.

… “This baby in the book? He grew up to be the smartest and handsomest and bravest hero ever. Do you know that story?”

“I know the story.”

“And he had a friend he loved more than anyone.”

“Patroclus …”

“This hero,” Mr Loguidice went on, “… He died young too.”

I hadn’t expected that. …[5]

Mr Logiudice and his wife know all too well what it means to be written out of history and it is only as the novel reaches its tragic end that we hear their true history as that of a married heterosexual couple with Down’s syndrome having to fight to keep their baby precisely because that baby is born ‘normal’ and ‘like people in history’ (that is not born with ‘Downs’). Numerous unspoken histories of exclusion and oppression operate by enforcing silence in the public domain and the story of people who live with a learning difficulty are one such. In this respect this novel is already an intersectional queer history that is being attempted not one focused on ‘gay’ identity, whatever that is, alone.

Nevertheless, Felice Picano has a point, when he says that he was fulfilling a felt need for ‘stories about the “everyday” gay world that existed all around us’, in an interview with David Bergman.[6] What was absent was not just a space for ‘gay’ writers that was not just a blending ‘gay and straight characters’ as Holleran, in the same interview characterises the ‘David Leavitt Period’ but a sense that what gay men (and we are just talking about men here note) did in ways in which their diversity and their rich potentiality as characters in novels was recognised. At no point was this a greater danger than in the 1990s when, as Holleran also says, ‘required gay writing to be about AIDS and nothing else’.[7] Hence my choice of Picano’s great AIDS epic, Like People in History for our focal point now. Because AIDS in itself needed to be seen as fundamentally something that became part of something much richer in the world of gay male characters, something that helped us know our own role in the happenstance misfortunes of the history of contingent events.

And the stress on how gay writers became makers of gay history employs the same basic ambiguity in the word ‘history’ as it does in Goethe or Carlyle. It is a name for the contingent events into which all people are ‘thrown’ in order that they shall make of them what they can and will, which is not always something worth making, and for the written and shaped form of those events in the hands, and guided by the perspective, of a visionary writer. Herbert Stewart, in an otherwise neglected and aged academic paper, makes this point so well, if in very dated terminologies, in relation to how Herbert Stewart says Thomas Carlyle, in the nineteenth century, responded to Goethe’s Faust:

… it is surely Carlyle himself who has warned us to remember the vast, unconscious, inarticulate movements, of which some loud-tongued apostle afterwards gathers the credit, but of which he was no originator, rather one of the least important symptoms. While we agree that progress has in some periods been immensely more rapid than in others, we can scarcely over-estimate the need to approach every period with reverent diligence, not knowing what we may there find, but radiantly expectant that we shall not find mere emptiness, waiting to see what new link in the great sequence it may enable us to insert, what unconsidered but very real phase in human growth it may teach us for the first time to identify. If there is one lesson which modern research has taught more forcibly than others, it is that we should not despise the day of small things, or call any part of man’s auto-biography common and unclean.[8]

There is a kind of heroism in the ways that the narrator and fictional auto-biographer of Like People in History transforms his artistic material, including wild parties of queerly enacted playfulness and confused but ennobling gay activism often too using theatrical metaphors for political action, such as ACT UP into the stuff of significant history. It’s transforming agent is that same writer referred to above, whose ascent is so often blocked by the convention, officialdom and sheer spite of the status quo:

“We’re going up!” I said, with tons of pseudo-decision in my voice.

“Name?” the man in unform asked, although he’d had me tell it a dozen times earlier that month.

“Sansarc,” I replied. “Roger.”[9]

As a writer Roger Sansarc in this novel creates or mimics events that have cast from the characters and resources in his ‘everyday gay life’, then transform them into a drama (which sometimes seems even to its writer a farce) before their metamorphosis into a massive David Copperfield like fictional autobiography. This is always done however against the force of the bitter reductionism that tries to see gay lives as ‘common and unclean’ and the ‘history’ that contains them as merely a collection of contingent random events.

That latter is represented throughout, unfortunately in a writing group vulnerable to accusations of misogyny, by a woman: Sydelle Auslander. It is she who overturns almost every attempted trial of to seek significance in his life. She provides the first quotation in my title where Roger overhears Sydelle’s damning review. What she says could, in fact, equally stand as an embittered review of the novel in which she appears from a certain negative homophobic perspective: “… a ridiculous farrago supposedly linking various allegedly important moments of homosexual history of the past century. Period. …”’.[10] It is worth noting the playful use of the term from punctuation and historical writing here: ‘Period’, because history is being remade in different perceptions and in the interests of differing and often conflicting groups, especially in the period of the first onslaught of AIDS, much of which forms the content of this novel in its iconic sweep across those ‘allegedly important moments of homosexual history’.

Picano often plays games with his relation to history, often to the discomfort of other writers who attempt to take a perspective on it as David Bergman shows in his prefatory comments to his book on the Violet Quill movement which Picano, Holleran and White themselves asked him to write. He has also pointed out in his non-fiction writing (as in his fiction, of which more in a later blog on The Book of Lies) his ambiguous relationship to how queer history is, and must (and it is a powerful mandate he takes on for himself) be conceived. The best book on The Violet Quill writers was actually suggested as a project to its author, David Bergman, by Holleran, White, and Picano, even though Bergman admits that: ‘Theirs was not my life, …’.[11] Yet, in his Preface, Bergman writes that Picano:

has written me (sic.) at great length about what he sees as the error of my ways. His advice has been generous, … , but I have not always revised the manuscript to accord with his views. … I am a different person with different investment in it and different interests.[12]

Picano gives way, it is clear to the views of what constitutes the truth of the historical period of which he is and was a part to few or no other perspectives on that ‘history’. Indeed, although in the Preface to Art and Sex in Greenwich Village he calls the position he was, as he claims, forced to find himself of a ‘historian’ an ‘unusual’ one, he nevertheless, ‘corrected younger writers’ often wildly erroneous views’. He also simultaneously claims an almost papal infallibility based on the ‘evidence’ of his own journals and what he claims to be an eidetic memory. But that claim is hardly the point, of course, since as one lives through the events that will go on to form the stuff of written history, the ‘historical importance’ of those events has yet to be established and may still be open to challenge: ‘we did know what we were doing in pioneering gay literature, gay publishing, and a gay arts scene; what we didn’t know was that it would end up being the scene, and thus of historical importance’.[13]

That last statement is typical of Picano’ tone and its ambivalence between assertion of truth and doubt about the final interpretation of the significance of those truths. The tonal quality I sense throughout nearly always accompanies a glance at the epistemological problems of history-writing and the contested nature of its meanings and the significance of its constituent parts. Nevertheless that tone still lays down with almost absolute authority a ‘truth’ that does not admit of ex cathedra error. An authoritative historian will, it is clear, know which people and which events matter in his (and it is so often ‘his’) narrative and interpret them in this light and with the right to name them thus. It is this false modesty that the fictional narrator Roger Sansarc shares with his author when he says, in the section I quote in my title: ‘whenever people of importance in the gay world were mentioned, my name always seemed to come up’. The tone of faux surprise is hard to miss. And this tone might be related to Bergman’s perception that Felice Picano was, though:

proud of being largely self-taught, he can become self-conscious in the company of highly educated intellectuals. When White asked him to lecture for his class at John Hopkins, he understood he “had been invited specifically as a commercially successful novelist” in contrast to “the artsy/literary business to which the students were generally exposed.[14]

In the case of the fictional writer, Roger Sansarc, we learn that he too is writing up too how and why his name has significance to queer history and queer writing – indeed ‘writing up’ himself, and what he does, alongside names of real historical characters that lend it some authority, like that of ‘his shy friend, Andrew Holleran’.

I think it is axiomatic that significance in history, as I have already shown in my reference to Carlyle, is signalled by a character achieving a ‘name’, ‘like people in history’. And hence the continual role-play in this novel involving acts of name-dropping that mixes true with fictional names and variations thereof. Thus a fictional gay male pop-star, Julian Gwynne, uses his acquaintance with the ‘real’ Lennon and McCartney to seduce Roger at the ‘real’ (and historical of 1969) pop-concert named ‘Woodstock’.[15] Names and naming of events (or sequence of events) or persons is the basic tool of awarding significance in history, their absence the stuff of an almost active forces of forgetting and / or oblivion. That is why, of course, people who seek significance they fear that they not, in any real terms, possess, drop names in lived OR written history and none of us is immune from this test of our authenticity as persons. In a publishing party for White’s Nocturnes for the King of Naples Picano met a number of people is initial description of which seems to want to denigrate (‘older, very dressed-up forty and fifty-year-old queens whom I didn’t know’ but who yet must be named (as Edward Albee, John Ashbery and David Kalstone’.[16]

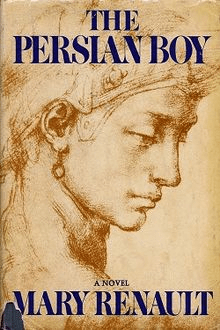

Likewise it is largely ignored and largely exclusively gay male real ‘artists’ like Holleran that tend be resurrected by Sansarc’s narration, such as John Rechy, a favourite from my own past reading, and Mapplethorpe. These ‘names’ get blended into the environment of Sansarc’s fictional status as a writer just as earlier, we saw happen to Andrew Holleran.[17] I have to admit that I still do not know if the Scandinavian named author Nils Adlersson actually exists but it is evident that he isn’t referenced on Wikipedia. Yet ‘Adlersson’s’ novels are compared to a novelist so well known by gay men at the time that only her most famous historical gay novel, The Persian Boy, about the life and famed gay love of Alexander the Great, need be named without needing to name her as Mary Renault. And then there are the ways that naming creates private or limited interpersonal significance in nicknames which I have already mentioned. My favourite instance is the name, Sansarc’s ‘great love of my life’, Matt,[18] gives him: ‘Mr. Myxtplqztrx’.[19]

The importance of that name in my view is not only that it is fictional and lives only in the most limited of real interactions, in a couple, but that it is literally unpronounceable. I may take this theme too far but I think it matters because of the stress on Matt’s own name, and the histories surrounding it, Matt Logiudice. Its origin as a name leads to confusion with the spinning of ‘rumours’ about its connection to Sicilian history and Mafia families that turn out to be entirely fictional., even though the novel never corrects them[20] When Matt tells the ‘true’ story of his parents’ bravery , it lacks naming the fact that that they have Downs’ syndrome and merely adds to rumour rather than history.[21] Sansarc more than once corrects people who pronounce the name in a way that is, in his view, incorrect. The most important one, although the insisted pronunciation is the same, is in the telephone call that informs Roger of Matt’s death.[22]

Here, and elsewhere, Roger insists that Matt’s family name is pronounced ‘Load-the-Dice’. One feels for the corrected administrator who is being corrected since most attempts I have come across to pronounce the nearest North American (European?) name to. It is the ‘nearest’ because Picano spells it differently and without the usual proximity to any (disputed) Italian origin. Is this spelling variation from a rather rare norm (Logiudice in Picano compared to the more ‘frequent’ (though not that frequent) occurrence in the States of the form, Loguidice). spelling variation. A contemporary American comedian pronounces this (her) name in a helpful Youtube video, in ways that have (except for the difference in the initial vowel) similarities to the administrator’s attempts and which stress an Italian origin. And, if it is Italian (or a Sicilian dialect) – it is registered as unknown in origin in another ‘helpful’ webpage with yet different recorded pronunciations – it infers the term ‘judge’ or ‘justice’ as a person involved in legal process, although for this reading the article before the noun would be incorrect in Italian (it should be ‘il’ not ‘lo’). This is then where I feel I may take this slim evidence too far but I feel committed to do so. Roger’s pronunciation is eccentric to say the least but its mimic phonetics raises the concept that is he reverse of the associations with a ‘justice’ or meaningful legal process, the idea of gambling on fortune -dice throwing, or even rigging, depending on your understanding of the idiomatic, ‘load the dice’.

Is this name then so contentious and misunderstood precisely because the novel stresses how difficult it is to be sure that you have named people in history correctly, with the correct meanings and linked interpretations of their actions as well as pronunciation of a name impossibly difficult name in a non-phonetic written script? Is this actually what is in contention throughout all of ‘history’ itself. Nowhere is this most important in the ways in which the contingent histories of a community in the process of emergence, like the gay community, and of an opportunistic (that is with a development based on random means of transmission, that become fixed as if they were facts) virus like HIV and its link, more manipulable and breakable than was though at the time except by ACT UP (and hence their importance in the novel to me) to AIDS and death. And this is important in this novel (and it redeems it and its author for me) because this is an AIDS epic , imagined and written in the thick of events, that makes that random connection between death and the history of a community and a virus meaningful in ethical but strictly temporal terms.

I would venture to say that the major theme of Like People In History is assisted suicide but that its heart lies in a plea is for the self-assisted ongoing life of a community exposed to the chances, throws of the dice as it were, of the random passage of time before it is shaped into a ‘history’ by writing and written up with justice. That ethical question is an old one in philosophy, as old as Socrates drinking hemlock for another reason. The two temporal sequences which make up this novel structured as sequential stories with an inset flashback in time to connect them in each chapter both end in an assisted suicide that need not be noticed as such and therefore made immune to public legal process. Alastair’s assisted death is based on a cleverly constructed lie that Alastair died without anyone the hidden fact of Roger turning off his ventilator being known. Indeed Roger turns it on again after his death to evade notice of his action. Since the whole most recent temporal strand of the novel concerns worries, discussed by Roger and his then lover, Wally, about whether it was just to give Alastair access to an overdose of Tuinal tablets (tueys). In the narrative from the 1990s Roger learns from Alastair that both of them were implicated, if Roger is so without knowing this to be the case, with providing Matt the means of ending his own life.[23] We know this concern matters, and was indeed a genuine question in the gay community, even if not related to being gay but by chance.[24] It is the same problem raised in that great neglected poem about the ethical ambivalence of a laissez-faire capitalism by Arthur Hugh Clough, The Latest Decalogue.

For ACT UP demonstrations, including that ‘real’ one in 1994 at Gracie Mansions mentioned in the novel, were about a society hegemonically straight, and therefore thinking itself wrongly immune to HIV, neglecting the preventable death of what seemed an entire gay community.[26]

Thou shalt not kill; but need’st not strive

Officiously to keep alive.[25]

I find Picano’s novel rich in so many ways but these, like others that I write more about and on this theme in a later blog, include ways of reframing the discussion of the homosexual and homosexuality, both in aetiological and ontological terms. Thus the processes of how his characters see the genesis of their own gay sexuality, whether exclusive or not, is compared between Roger and Alastair to see how ‘like’ each other they actually are. As always in other Picano novels I know even centrally compared characters are not very like each other in any terms, apart from being white men. The way characters reflect on the meaning of their sexuality too suggests a queer openness to difference rather than one gay identity. This, I think is more the case in The Lure. Yet Roger reads Kinsey early in his life to spark his reflections and Alastair sees himself as somewhat different to ‘fully, openly, homosexual’.[27] The sense that what it meant to become or be gay is by Picano seen as ‘emergent’ with fuzzy definitions, and it is this precisely I’d like to discuss in my next blog, although there is a key statement of the theme here:

This entire “gay” business was still so new, so unprecedented, how could we know what we were doing? We were just trying to do things right. which meant not as heterosexuals did them, or not as our parents and teachers did them, …[28]

I think the most appropriate way of ending this however is to show that, ‘self-taught’ as he may be, the literary analogues of what Picano does in this novel run deeper than Dickens, though I’ve mentioned David Copperfield several times as pertinent to thinking about this novel. In a discussion involving the lawyer who resembles the probably fictional Nils Adlersson, the purpose of fiction is discussed in comparison with that of ‘history and biography’ is raised. The discussion of the role of fiction in comparison with history is at least as old as the reflections (or ‘Apologie’) of Sir Philip Sydney. Alastair’s answer to this question is probably that of Picano and it makes no assumptions about what it means to be gay, in terms of either becoming or being gay. It is as simple as this – that if you want to know what it is like to be gay you need more than one point of view. ‘… What’s the point of reading fiction?:

“to discover other points of view!” … “Too find out how other people live. What they experience. What they think about that experience. How they feel about what they think they’ve experienced. …’.[29]

Thus fiction is a means of answering the question too about what the fuzzy boundaries of gay life feel like in a community, something I now prefer to call ‘queer’ life. And that is so too in genres of fiction we might not expect to be addressed, such as the crime thriller. But that is for my next blog on Picano.

[1] Picano (1996: 478)

[2] ibid: 309. My italics.

[3] See 1.1 in https://www.lexico.com/definition/stodge

[4] ibid: 491

[5] ibid: 497

[6] Bergman, D. (2021) ‘The Violet Quill Club, 40 Years On’ in The Gay and Lesbian Review Worldwide (January-February 2021). Available at: https://glreview.org/article/the-violet-quill-club-40-years-on/

[7] Andrew Holleran interviewed in ibid.

[8] Herbert L. Stewart (1917: 589) ‘Carlyle’s Conception of History’ in Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 32, No. 4 (Dec. 1917), pp. 570-589 Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2142053 (Accessed: 14-04-2021 07:55 UTC)

[9] Picano (1996: 3)

[10] Picano (1996: 478)

[11] Bergman, D. (2004: Location 106) The Violet Hour: The Violet Quill and the Making of Gay Culture New York & Chichester, Columbia University Press. Kindle ed. cited.

[12] ibid: Location 121.

[13] Picano, F. (2007: 2f.) Art and Sex in Greenwich Village: Gay Literary Life After Stonewall New York, Carroll & Graf Publishers.

[14] Bergman (2004: Location 541)

[15] Picano (1996: 138f.)

[16] Picano cited Bergman (2004: Location 541).

[17] ibid: 293 & 396 respectively.

[18] ibid: 286

[19] See ibid: 313ff. for instance

[20] See ibid: 352ff.

[21] ibid: 233c.

[22] ibid: 503

[23] ibid: 507

[24] See for instance ibid: 56, 275f, 420f.

[25] ll. 11f The Latest Decalogue by Arthur Hugh Clough (1819–1861). Available at: https://www.bartleby.com/71/1423.html

[26] See for instance ibid: 100ff.

[27] ibid: 123 & 141 respectively.

[28] ibid: 310

[29] Ibid: 190

18 thoughts on “‘“… a ridiculous farrago supposedly linking various allegedly important moments of homosexual history of the past century. Period. …”’. ‘… , whenever people of importance in the gay world were mentioned, my name always seemed to come up. … ’. Writing up a name in queer history: reflecting on the gay epic in a time of AIDS in Felice Picano’s (1995) ‘Like People In History’.”