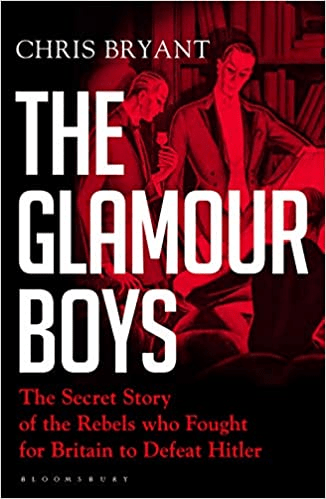

‘… half in love with the male camaraderie of the regiment’. Reflecting on the contribution to queer history as a side-effect of Chris Bryant’s (2020) The Glamour Boys: The Secret Story of the Rebels who Fought for Britain to Defeat Hitler, London, Bloomsbury Publishing.

Chris Bryant MP is described on the flyleaf of his new book as the ‘first gay MP to celebrate his civil partnership in the Palace of Westminster’. His Wikipedia biographical information shows that though a member of the Labour Party since 1986, his political affiliations, and any prediction that might have been made merely from a surface ‘judgement’ of his education, were originally with the Tories. This book is, I would suggest, first and foremost a book for people in love with British (perhaps even just English) Parliamentary politics. For the true hero of its pages, and why perhaps it is not a book I will keep though I enjoyed it immensely, is the institution of Parliament as a haven and home for the individual and non-conforming persons supposed to staff it who put other things before slavish admiration for party or political cause. Once this book has established a linear narrative it is one entirely reliant on the thrills and turns of Parliamentary debate, wherein voices antagonistic to Fascism in Europe, and in Britain, assert themselves against those antagonistic to a Parliamentary role in the decisions of Government, that circled around Winston Churchill.

The great villain of the piece therefore is not Hitler primarily as such but the forces which colluded with him, even without being, in any way, committed to fascism, in the form of Chamberlain and his government. The Neville Chamberlain, who becomes the eminence grise of this book is one characterised by the assertion that he, ‘found Parliament an inconvenience and admitted that he salivated at the idea of suspending it for a couple of years when he was told that his French counterpart was contemplating doing the same’.[1]

Of course, that being the case, we have heard this story told many times though it is told here with great narrative drive, energy and excitement as the fortunes of the anti-fascists improve and recede with events. If you like this kind of account of the drama that the events of Parliamentary democracy provide, you will like this account. But this isn’t the book I had hoped and was promised by its prelude to this narrative. One feature of the danger to parliamentary democracy posed by Chamberlain is his willingness, a willingness that has never lost its appeal to autocratic Prime Ministers, to play parliamentary games involving ‘dirty tricks’. His chief aide in this job, as this book tells the tale is Sir Joseph Ball described by Bryant in the caption to his photograph as, ‘the former intelligence officer’ appointed by Chamberlain, ‘to run a black-arts operation for him’.

These arts were used against the high preponderance of those parliamentary enemies of Chamberlain’s appeasement policies who were identifiable as queer or possibly queer was to tap their phones , threaten blackmail and use tricks that denigrated them. These tricks were also used as Jewish people who stood in Chamberlain’s way, such as Leslie Hore-Belisha. That is yet another story but it is to the credit of the Glamour Boys that Bryant presents them as, unlike the awful Nancy Astor, as enemies if anti-Semitism. To this end Ball bought up the magazine Truth (the organ of Henry Labouchère of the infamous amendment that criminalised homosexuality) and helped propel a campaign of smear in which coded language was used against them, including the title ‘the Glamour Boys’.[2] Strangely enough, this campaign against people who could be abused by merely using the term ‘bachelor’ in a highly coded fashion, can also be seen as part of the struggle against a male-dominated organ of power that the ‘homosocial’ world of Parliament actually was.[3]

The use of the term ‘Glamour Boys’ as a form of denigration of a set of MPs, not all ‘bachelors’, is the fact that unites the two parts of this book. The second containing a fairly straightforward linear account of parliamentary struggles as described above, the first a resumé of the lives of the featured ‘Glamour Boys’, including the kinds of evidence that might have been used against them of a life in which the love of men, including sexual love, was prominent if not exclusive or, to them, definitive of their identity. It is this part of the book that fascinates readers of queer history, although not by having providing any great clarity about the ways in which these men can be called ‘gay’ or not. Indeed, it deflects from that question and perhaps rightly, since identity is the not the key to an effective queer politics, nor does it nullify the fact that these men’s vulnerability to blackmail or public humiliation was also, in a sense, the reflex of their access to great power, status and control of self and others.

I think Bryant does not help in any way to help us gain this clarity though he provides many necessary facts we would need to use to take on the project. As always, there is a sub-cast to these books of working class men upon which the lives of ultra-powerful queer men were dependent but time with whom could be purchased relatively cheaply and often whom could be used as objects onto which those same powerful men could project some fairly intense self-loathing. But the story is far from as simple as that, and there is a sense in which the lives of the ‘Glamour Boys’ can also be illustrated to show how they could, within strict limits, change their ideas about the relationships between the classes, in so far at least as this applied only to males of either class. The latter is a limiting factor I won’t deal with but it is necessary to consider by any intersectional feminist history of the period, which I can’t provide.

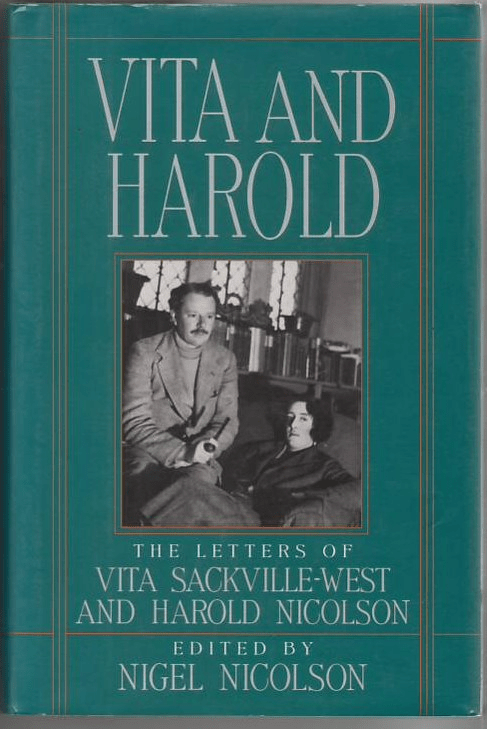

The main dramatis personae that make up the Glamour Boys all occupy a privileged and entitled white upper class who occupied high position across both the Tory, Liberal and some parts of the Labour Party. Of the latter, we need to include Harold Nicholson. His marriage to Vita Sackville-West (a model for the queer sex/gender transgressions of Virginia Woolf’s Orlando) allowed each to continue same-sex, and other, love affairs. Yet he disliked the ‘decadence’ implied by the visibility (calling it a ‘fungoid growth’) of Vita’s brother, Eddie’s queer, since it threatened to compromise the ‘reputation’ with which he affronted power.[4] He in particular demonstrates a world that was openly aware of the usefulness to him of places where he could cruise available working-class men like guardsmen and sailors, such as in the equivalents in Berlin of the Savoy Baths at 97, Jermyn Street (link is to my blog on this). Yet he also, as Bryant shows, says that: ‘the idea of a gentleman of birth and education sleeping with a guardsman is repugnant to me’.[5]

Harold is an elder amongst the Glamour Boys however and it is clear that his repugnance was as flexible as needed when a Second World War, this time against Fascism, opened up a world of young men like Jack Macnamara, who, though himself also of an entitled class, spoke of youthful male camaraderie across classes. In 1939 he was 52 (seems young to me these days) when he told of Jack’s inclusion in a meeting with Harold of nine signalmen from the London Irish Rifles from his own regiment. The story opened up a much more democratic cross-class-category set of feelings, hinted at in his diary record of this event: ‘… “Why I like young men is not really that I am homosexual but hat I have a passion for my own youth”….’[6] Jack MacNamara himself (in the record he appears to be named John after his father) devoted his energies, whilst still a Tory MP to ‘revitalising the London Irish Rifles’, his Territorial regiment. I cite Bryant’s summary assessment for the reasons of this in my title. It appears that it was possible to entirely identify his sexual feelings for men with the ‘half in love’ passionate engagement he felt those men needed in order to be reborn as a unit:

… brimful of energy, determined to face the Nazi challenge and half in love with the male camaraderie of the regiment, Jack …, as the official history of the regiment put it, “… helped to put a new zest and energy into the battalion”. It helped that nobody in the regiment seemed to care that Jack was openly attracted to men. …. (My italics).[7]

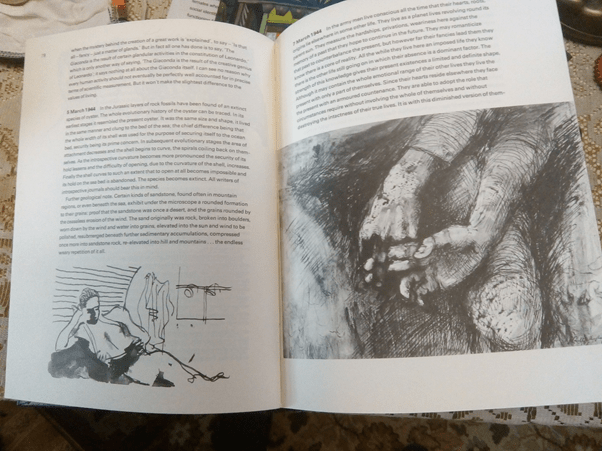

The relative openness of the fact that sexual relations between men (and indeed men of different social classes) were possible and, (given no other options for some) acceptable for many, is an important factor in assessing queer life around the period of the Second World War, whatever the prejudices and stereotypes employed and revalidated in the public realm by Chamberlain and Ball. And this arena of a more fluid sexuality existing across supposed sexual identity categories is clearly implied too in the drawings of men in barracks, though these are conscientious objectors, by Keith Vaughan, that I write about, in relation to another topic in another blog. Here is the relevant bit, referring to the drawing of soldiers’ hands from Vaughan’s 1950 Journal and Drawings:

The drawing appears on page 79 alongside text from the Journal referring to 7 March 1944, which discusses how married heterosexual soldiers form inside the camp, ‘all contacts, friendships, love affairs’.[3] The implication is clear. Heterosexual men can form contacts, friendships and love affairs without compromise of their heterosexual marriages because they do not need to ‘involve the whole of themselves’. …

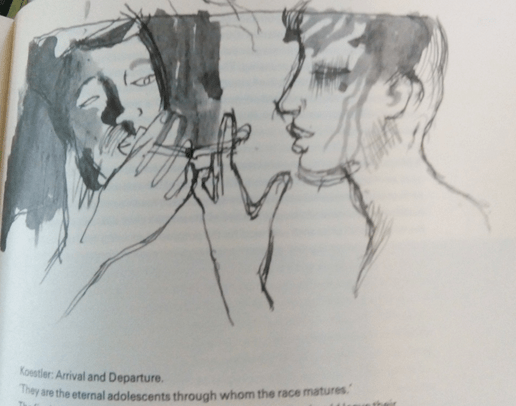

Vaughan’s fascination with masculine sexual behaviour is discussed frankly in 1950 … For instance, his paintings often deal with ways in which men could engage each other in ways that were not obvious to an outside view. One such scenario was the sharing of the lighting of a cigarette, as in this example from one page opening before the Study of Hands:

The progress of sexual desire between men is not hidden but it may be occulted, which was actually the effect of illegality and mores that were far from being shared by all. Vaughan’s Journals and Drawings reproduces Vaughan’s own photographs of naked young men at Pagham Beach from 1939 and later with the all-male bathing pools of Hampstead Heath. There is no need to reference Vaughan’s erotica from the 1970s to show that he could draw queer content.[8]

And this were relationships like those of MacNamara and his regiment between classes. The point is made even more explicit by John Lehmann, poet and former Bloomsbury member and then publisher in a novel that is very nearly documentary and autobiography, In the Purely Pagan Sense, published in 1976 but writing of the 1920s and 1930s, and using Havelock’s Ellis term for homosexuality, inversion:

… inversion, moving vertically through society rather than horizontally, can give the homosexual a far greater experience and understanding of his fellow men than the ‘straight’ young man, marrying into his own class and staying in it, can ever have.[9]

Now Lehmann was a liberal and had started his political life, like Stephen Spender and W.H. Auden, much further to the Left. The term ‘Homintern’ was often used to describe the set surrounding him in ways that conflated fears of both Communism and a decadent and destabilising queering of sexual and gender norms, by Jocelyn Brooke, for instance who used the term ‘homocommunism’, as noted in Gregory Woods’ wonderful 2016 book, Homintern: How Gay Culture Liberated the Modern World.[10] Leftward leanings, of a Tory kind, could be found in the Glamour Boys, even Labour’s Harold Nicholson. MacNamara was besotted by his assistant Guy Burgess, who fed Tory Government secrets to the Soviets from him and more influential Tories who expressed approval of the size of Burgess’ ‘equipment’.[11] But the assistance to International Communism, or Russian expansionism more truly, was here not deliberate.

Others of the set were attracted to the working class oriented Nazism of Ernst Röhm before it was clear that he would not be favoured by Hitler, and was indeed murdered by the latter’s henchmen in the Night of the Long Knives.[12] If guardsmen were available in the bathhouses, few aristocrats had to tread that far to recruit young working class men by offering employment. Lord Beauchamp, the friend of Rob Bernays, had a personal domestic service employment policy that was noted by some to show that Beauchamps deserved, “great credit for his taste in footmen”.[13] My own feeling is that there was never much more than nuance to the class fluidity illustrated by the patriotic nationalism of the Glamour Boys, although their politics would be nearer to those of Harold Macmillan than Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s. A fairly typical story of their exploits was Jack MacNamara’s legendary pub-soldier crawl in Colchester with the artist Arthur Lett-Haines. As Bryant says: ‘It was not difficult to guess what a ‘pub-soldier crawl’ involved, …’.[14]

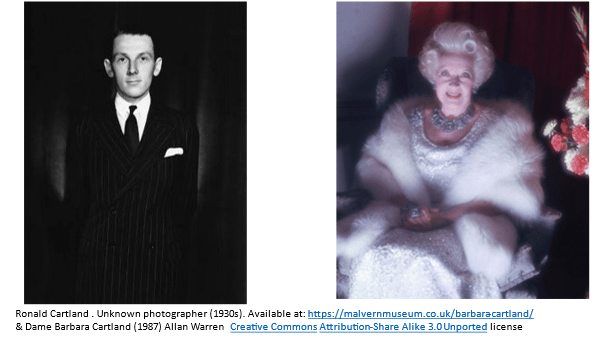

Perhaps the hero of this book, before that hero turns out to be the Mother of parliaments itself, is Ronnie Cartland, who turned down a direct invitation to the Nuremberg Rally from Hitler himself.[15] Bryant presents Ronnie’s contribution to the debates with which the anti-appeasement MPs badgered Chamberlain and upset the Tory Parliamentary whips, to great danger to themselves if they were ‘bachelors’, as being unusually direct and effective in its ironies: ‘It was a mystery to him that Chamberlain refused to defend democracy and resist aggression’.[16] According to Ronnie’s sister, the romantic novelist Barbara Cartland, ‘she had been told’ by worried Tory MPs, ‘that people like Churchill and her brother should be shot’.[17]

This is a really worthy book that offers a lot of detail in characterising queer life in the mid twentieth century.

Yours Steve

[1] Bryant (2020: 283)

[2] 5th page of glossy photographs between ibid: 270f.

[3] ibid: 165

[4] ibid: 55

[5] cited ibid: 55

[6] ibid: 281

[7] ibid: 232

[8] Extracted from my blog: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2021/03/09/not-made-with-hands-a-shaggy-dog-shaped-reflection-on-the-limits-of-curation-as-a-model-of-historical-knowledge-a-queer-problem-in-the-history-of-art-based-on-reading-the-human-touch-making/

[9] John Lehmann (1976:8) In the Purely Pagan Sense London and Tiptree, Blond & Briggs Ltd.

[10] Gregory Woods (2016: 177) Homintern: How Gay Culture Liberated the Modern World New Haven and London, Yale University Press.

[11] Bryant, op.cit.: 162.

[12] ibid: 58ff.

[13] cited ibid: 80

[14] ibid: 136

[15] ibid: 155

[16] ibid: 287

[17] ibid: 261

2 thoughts on “‘… half in love with the male camaraderie of the regiment’. Reflecting on the contribution to queer history as a side-effect of Chris Bryant’s (2020) ‘The Glamour Boys: The Secret Story of the Rebels who Fought for Britain to Defeat Hitler’.”