‘Wood moved freely among Paris’s most elite artistic circles as he experimented with various post-impressionistic styles, bisexuality and opium. …/ However, his opium use, financial concerns, and dissolute lifestyle eventually led to serious psychosis. … The inquest ruled that it was “suicide while of an unsound mind”’.[1] Does the history of art as a discipline on its own really have the skills, knowledge and values required in order to reflect adequately on the value of shortened lives? Reflecting on the case study of Christopher Wood in Angela S. Jones & Vern G. Swanson (2020) Desperately Young: Artist Who Died in Their Twenties, Woodbridge, Suffolk, ACC Art Books.

There is a kind of academic mode that sees its role as rescuing lesser people from folk myths. I remember experencing this in action when I signed up for an MA in the History of Art supposedly taught openly and at a distance that still devised vanity projects to show off its lecturers. In the first of these the topic was breaking the myth that associated visual creativity with ‘madness’. Keen to prove that artists actually looked circumspectly, and from a distance, at the ‘mad’, the aim was to break the Romantic myths that accrue around, more than in any other case, Van Gogh. What people got who went there was a monologue from a person unqualified to speak of mental illness but who nevertheless felt able to peddle without even thinking about any possible pain, fear (or legitimate anger) that might be caused in her audience by careless and common stereotypes of the mentally disturbed. An interest of producing descriptions that were, what is called, ‘objective’ pre-domoninated. The same could have been done, and often is, about suicide without the speaker embracing the saving grace of at least some reflexivity.

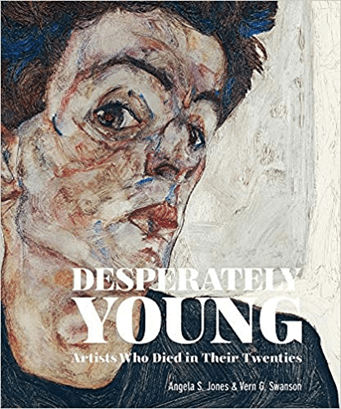

Of the early death of artists and poets there is an abundance of myth to unpick. Jones and Swanson contrastingly provide some fascinating case studies of those who died from any cause in their twenties across the whole range of the history of modern art from the Renaissance to the present day. It needed saying therefore that the data probably would not in this duration of time support the romantic notion of the special stress on creative young minds that might cause them to die early. Most examples in the longue durée of early death could not support such a hypothesis because of the high mortality rates prior to effective medical interventions. Their sample was necessarily highly selective since it depended on the survival of names otherwise forgotten to history. The bias is to people of accepted social stature or access to the ‘stature’ of others, such as the children of great artistic parents. Most artists died for the same reasons as their contemporaries who remained unknown. Indeed, such was the indifference of urban public poverty, even to those guarded by private wealth, that disease could still take from the privileged few though it enjoyed greater sway amongst the many who matters not at all to the academic history of art. Tuberculosis may have its own romantic myths as a cause of early death but it was a disease precisely fostered by urban public poverty (usually called ‘unsanitary conditions’ to naturalise the purposive nature of its maintenance amongst the many by the few), especially in large cities to which artists flocked. Hence the facts that ‘made their stay in the Eternal City’, (Rome, of course) ,‘ironically short’.[2] The same can be said of Paris in the nineteenth century and the many Romantic young men from David’s studio such as Jean-Germain Drouais and the lesser known Léon Matthieu Cochereau died young.[3]

What surprises us in the book is the quality but, nevertheless, ordinariness, of the artworks left to mark these young men and women on the large, particularly in the children of better know parents like Zurbarán. His son was named Juan and his work is described as that of ‘primarily a table-top still life artist’.[4] There are obvious candidates for inclusion in such a book of course. Thus, Aubrey Beardsley, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Egon Schiele are inevitably included.[5]

Yet neither myth-making nor ideology ever stop being produced by histories of any phenomenon and I think the authors are wrong to exclude it even when it happens after the event, as in Ali Smith’s use of Pauline Boty in her novel Autumn. Smith builds from Boty’s case usable myths about the fate of women artists in the interests of a less skewed public knowledge. I would suggest that Ali Smith will in fact have done more for the recognition of Pauline Boty as a serious female artist that these authors, whom, rather snotily in my opinion, describe her ‘colossal status’ as merely an aspect of ‘her self-perpetuating iconic stature’.[6]

Myth is vital to the understanding of some artists and the relationship between the art of the past and the present. This phenomenon is well known in literary history given the importance of Thomas Chatterton to the Romantic poets and Victorian poets. Browning was a fan and student, whilst George Meredith the artist’s model for Chatterton in the iconic painting of his death by suicide in the art of Henry Wallis (1830-1916). This is, in fact, particularly the case with a case study I take from this book to characterise some issues in how the history of art taken as a single discipline oft misrepresents history and the complex interactive processes of how history is ‘made’ by a reliance on the mythical pseudo-science of a past age of positivism. Virginia Button’s very fine short introduction to Christopher Wood in contrast has to rely on the concept of folk and romantic myth, and a tragically understood ‘cult of youth’, to explicate Wood’s significance.[7]

Henry Wallis The Death of Chatterton. The model for the young Chatterton was the young George Meredith. This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA. Henry Wallis The Death of Chatterton. The model for the young Chatterton was the young George Meredith. This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA. |

Button argued in 2003 that the early and tragic death of ‘poetic’ artists was part of a ‘template’ for the myth around Wood. His friend, the artist Winifred Nicholson saw him in one letter as coming, ‘up the valley with springing step of youth’. Button insists that, even if ‘on a subconscious level’ the parallel to the ‘romantic poets’ like Keats and Shelley, (‘even down to the ‘Byronic limp’, since Kit walked like Byron with an uneven gait), would be ever present to Kit’s contemporaries. It would be especially so to those whom Nicholson said, like herself, enjoy, ‘the regions between poetry and art’.[8] The critic Eric Newton saw Kit, as, like Van Gogh in, since both, ‘having tasted all things, could raise them to a higher power …’.[9] Jean Cocteau, an early lover of Wood, wrote to Wood’s later lover, the poet Max Jacob, that Wood ‘was only lent to us’, from angels. [10]

Button herself fails in some ways to understand aspects of queer history but I think this comes across clearly in relation to better understandings of Wood coming out of the more recent Pallant House gallery exhibition wsith a specifically queer agenda. One way of pursuing what the absence of mythical icons is in our approach to artists who die young is to look at how the absence of this perspective impoverishes the cross-fertilisation of understanding of artistic projects as they were understood by those who created them. Richard Ingleby’s biography of Christopher Wood points out that both the European Neo-Romantic queer painter Christian Bérard and the colourist painter Winifred Nicholson compared Wood to Masaccio, as if the comparison had been portentous of a similar end in sight.

Tomasso di Giovanni de Simone Masaccio The Tribute Money (1425) wall fresco, 247 x 597 cm. Brancusi Chapel, Florence. This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND. Reproduced ibid: 111. Tomasso di Giovanni de Simone Masaccio The Tribute Money (1425) wall fresco, 247 x 597 cm. Brancusi Chapel, Florence. This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND. Reproduced ibid: 111. |

As Nicholson said to Frosca Munster after Kit Wood’s death: ‘Masaccio would have understood Kit better than any of us. They both have the same life, the same grasp of reality’.[11] The sources and justifications of a shared myth of an artist’s life are valuable to understand but Jones and Swanson do not help to further that understanding other than in pointing out that he was the ’most famous and influential’ of the artists they talk about although he is now, paradoxically, ‘known only to artists and art historians’.[12]

I believe that Wood himself never seems, at as far as biographer Richard Ingleby’s account of his death goes, to mythicise his death, despite the fact that there Ingleby believes Wood was ‘very aware’ of the many possible correspondences between his fate and that of Van Gogh.[13] Where his suicide cannot be explained by opium fuelled paranoia, it seems to me it sprung from practical difficulties facing WWood rather late in his life: notably the problem of sustaining his life through his own autonomous means rather than those of a mother, OR an older devoted (and extremely wealthy) male lover or an heiress to the Guinness fortunes. All of these might have been prepared to support him financially, as it were, forever. Whereas lovers oft give way to threats of their love being taken from them, his last patron-qua-dealer, Lucy Wertheim, remained business-like when on the 27th of July 1930 Wood, on the 40th anniversary of Van Gogh’s possible self-shooting, said to her, ‘…if I can’t have this sum I’ve made up my mind to shoot myself’.[14] That is non-committal but chilling. When he threw himself before a train on 21st of August 1930 he imagined he was followed by spies set on him by the Guinness family, keen on saving the Guinness fortune from a hunter of the same in the shape of their daughter Meraud.

No-one currently seems to interpret his death in ways that allow us to believe that the Guinness family were distorting a scenario of Kit’s motivation that they may have had some rationale at its base. For Wood, the act of actively ‘making’ a living was not something he knew well. Being kept was his norm of life as for other beautiful young men associated with age and/or celebrity. Of course, young men age and, although their lovers change too in more ways than getting even older, those changes are never as sure as those in which beauty associated with the youth of the person in the subordinate role in such relationships disappears. There is far too little written on Wood’s early artistic fantasies in which excess is associated with the availability of the body or its flexibility to help me support this argument, even by our best commentator thus far, Katy Norris. But even the early and less well-known paintings seemed associated with such themes. Indeed the artwork that might demonstrate Wood’s queer dilemma and its peculiar economic factors wasn’t even drawn to the fore before the Pallant House Gallery posthumous retrospective in 2016.

Katy Norris in the catalogue describes ‘the slender, muscular bodies of the stylish young men in an erotic painting entitled Exercises’ but that is ALL that is said about this painting that I can find.[15] Hence we have to piece together the human material underlying her perception that Wood found a ‘seamless’ connection between a simple art that served a very idealised version of what was a dying economic model of what working for a living actually meant. It was something we’d intuit done with the hands not the head primarily: where a ‘simple painting style’ , perhaps like that of ‘primitive’ Alfred Wallis, matched ‘spartan existence’ in the fishing villages of English Cornish or French ‘Breton’ culture.[16]

The most iconic of these earlier paintings, all kept in the private collections of people who, by and large, were both rich (or connected to the rich) and ‘privately’ queer (small cliques can be described as ‘private’) like Eddy Sackville-West and Mattei Radev, is Exercises of 1925. As the Head curator of Pallant House, Simon Martin, has suggested, in 2018, that an ‘objective selection of works, not leaving out those that may be deemed controversial or expressive of an artist’s sexuality’ was not commonly the normative practice in the ‘curatorial process’ before the advent of explicit queer curation.[17] And though I agree that there is no doubt that Exercises ‘may be recognized as ‘queer’ by some visitors but not necessarily by many others’,[18] what speaks from this painting is mainly the opulence that associates exhibition with private ownership and a flexibility of embodied male sexuality to variations of public/private visibility and bodily touching. This is a painting that plays with what the expensively clothed and accommodated males in the relaxed comfort of a luxurious home do not see, or at least do not publicly acknowledge.

The range of exercises varies the muscle groups and domains that are visible as does the presence or absence of swim or gym wear. The pool has curtains that both conceal and reveal, The positions and gestures will seem sexual or like foreplay or neither of these to some but not to others – although it is clear that at least two men are positioned in touch and / or visual proximity to other men’s penises. Whilst others look down or away. The room is as most lounge and/or theatre as it is a private indoor poolroom. It is 5 o’clock on the timepiece shown but no-one stirs to leave for or away from ‘work’, because this place is not work. Hands brush or touch – in the clothed men they are hidden in pockets or behind a lounging head. They don’t work – unlike the hands we will see in some of Wood’s boat-building fishermen in the paintings later identified by the Nicholsons as his best work.[19]

Exercises is NOT a painting about upcoming death though suicide even if it evidences ‘experiment’ with queer sexuality. The connection between these categories anyway may only mean something to the died-in-the-wool homonormativity of what ‘traditionalists’ like Jones and Swanson call both life and art. For if Wood was ‘experimenting’ at the time of his death, it was, in public at least, with varied forms of a heterosexuality relatively new to him including sex with the fellow artist Frosca Munster, plotted marriage to Meraud Guinness, or a putative adulterous affair with a ‘real woman’, the term he used for Winifred Nicholson, the then wife of the sexually unsatisfied Ben Nicholson, who was (soon after Kit’s death) to leave Winifred for Barbara Hepworth.

Now you can’t earn money with niche markets but Wood increasingly played with a desire to paint for a market without compromising his bohemian image too much, hence his turn to the Nicholsons and a new ‘simple style’. But Tony Gandillaras, the rich bisexual diplomat, once ‘kept’ Kit financially afloat almost without any transactional exchange being evident, just as the poet-artist-dramatist Cocteau kept Jean Burgoint. When Wood painted Jean he did so as Boy with Cat (now in Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge). Here Jean plays his big hands over a kept creature but the Siamese is also alert, and has open claws so that either flight or fight is possible.[20] Moreover when Wood creates for the market – a dressing screen for instance, only women are displayed displaying themselves: the men work hard and with strain – their straining hands used to row ashore or in pulling in nets from the resistant sea on ropes.

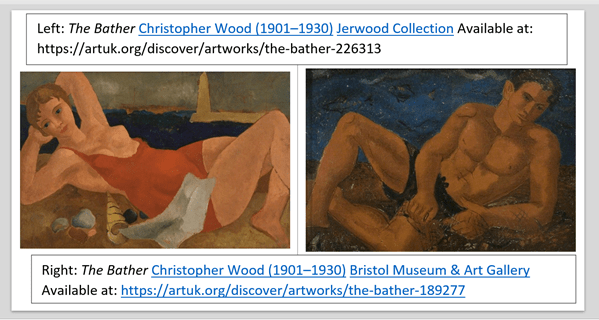

When he responded over two years afterwards (1925-6) to Diaghilev’s ballet Le train bleu he painted semi-nude models (male and female) in the Chanel-designed swimwear that was used in that production.[21] Sometimes this art is both erotic and playful. In his 1926 female nude The Bather, a debt to Picasso’s self-displaying Spartan beach nudes of his classical figurative period combines with playful phallic imagery of horn and lighthouse. This playful erotic is less easily achieved in the male version, where huge hands sort of fiddle, rather than work, with a fishing net, whilst our attention is drawn to a beautiful torso. The hands even, I would hazard to say, indicate the otherwise unseen phallus.

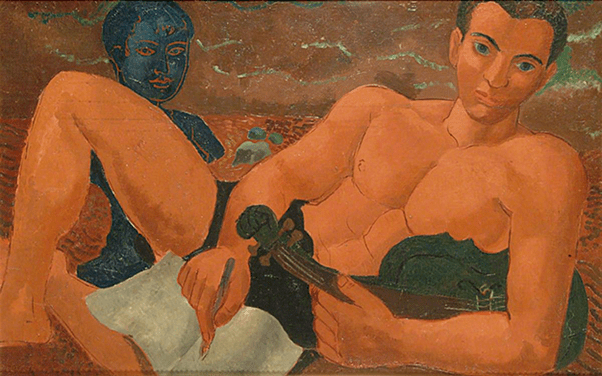

In the playful art version of this nude, the model is Constant Lambert, the bisexual or ‘questioning’ composer. Andrew Motion seemed unaware of this portrait, although he speaks of the clothed version, in 1997. Whereas modern biographers of Wood tend to find some sympathy with how tiresome Wood found Lambert’s prevarication with Wood in the wake of the Pandarus-like attentions of Diaghilev as the latter tried to create the team for an English National Opera House production of A Lambert score. Though much remains unsaid, Motion’s sympathy is clearly with Constant:

… Wood’s letters home from Paris to his mother indicate that their real personalities were widely different. Constant was beginning to take refuge from his uncertainties in boozy conviviality, … Constant veered away from intimate entanglements, Wood was a committed homosexual; Constant drank, …; Wood was a heavy and regular user of drugs.[22]

Apart from the fact that it is interesting how far away this assessment is from Jones and Swanson’s notion that Wood ‘experimented’ with bisexuality as freely as he exchanged modernist painting styles with each other, and that it led to his paranoia and suicide, this account is clearly very one-sided and veers to the norm of the stage of development paradigm of queer sexuality. The latter may have appealed to Motion at that time, having published a novel of schoolboy attachments to men in 1989.[23] Even more so, when Motion says that Wood’s attitude ‘smacked of queenly intolerance’, he goes too far in that direction of heteronormative entitlement.[24]

When Constant appeared as ‘The Bather’ he is awarded the same huge purposive hands as the earlier type of the male bather already discussed. Constant’s hands though clutch instruments of the composer’s artistic creation, a pen writing a score and a violin, although playful phallic suggestiveness remains, I think. Then there is a shadowy male observer of Constant in the shape of a blue-tinged bust overlooking the nude’s generous torso. Here work is still playful and gets away with it, in ways fisherfolk don’t quite, in the ‘primitive’ paintings. Artists after all aren’t working in life and death situations with skeletal half-built boats.

This kind of artist suspended between play and purposive work is also recreated in Wood’s famed self-portrait in front of a Montmartre rooves skyline where Wood’s hands are glamorously enlarged, his paintbrush held in phallic position and he wears, as everyone would have recognised at the time and continue to do so, a Harlequin jumper meant to recall those of Picasso’s Blue and Rose periods.[25]

Even after his period of infatuation with idealized rural fishermen, amongst whom he too easily inserted Ben Nicholson as an idealised sailor home from sea, the tension between creating pictures that might sell (of interchangeable rural Cornish and Breton coastal villages, based so often, as Françoise Steel-Coquet said in 1997 on holiday snapshot postcard scenes and a love of Keatsian flight from responsibility with a deathless bird) was sorely fought.[26] Such tension is expressed at its best in the free-hand beauty of his drawing of a sleeping fisherman, idealised and romanticised, of 1930.[27]

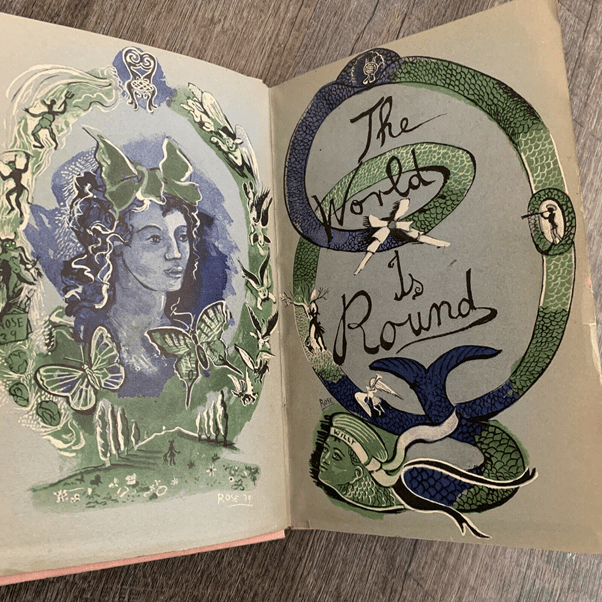

That this tension was being fought is clear in queer readings of the Breton pictures but I think it is best suggested in his most beautiful paintings, those of a Nude Boy in a bedroom based on the openly gay Francis Rose though later married artist and supporter of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Tolkas (and illustrator of Gertrude’s character (based on him?), wandering Willy of the Stein novel The World Is Round. Willy, of course, slippery happy little fish that he is, always returns to his cousin Rose., who inrends turns out so not be his cousin (but what is acategory label) that he marries her.

We need not know about Francis Rose however, though Rose would have differed in that opinion I am sure, to see the iconic qualities of the kept boy in those beautiful paintings, torn between a life of idealising Breton or Cornish ‘real women’ and a game of fate or chance in various bedrooms not his own. I find it quite tragic as with all those paintings that bear the Wood motif of playing, or sometimes Tarot, cards.

The main source of tragedy here is the enclosure of the boy in the room that is emphasised by the various states of play of the open window to a freer sea, as with Stein’s The World is Round paradoxically. The nude boy contemplates the real and older black and white image of the Breton woman (dressed as if for a Gauguin painting) and Tarot cards most visible at an image of a joker. His back is to the sea, although exposed to whoever might ‘keep him’ (in both senses) in his room in the sadder less well-known and less shuttered painting. These paintings mean so much less out of the queer context they illustrate. Their tragedy is not of a boy who ought to have chosen a normative role as the lover of real women, that of a ‘real man’, restless for a real woman, like Ben Nicholson, but of the trappings of the normative itself, such that the queer is constrained as pure private play and decoration. Yet the forces that shut out the histories of personal and social queer experience remain in force,

One maintenance factor is I think the arid history of art and its delivery in and through hierarchies. Hence my feeling against Jones and Swanson, who are nice people who feel they have the authority to rank art in terms of people (possibly ‘countless unlisted souls’ goes their rather patronising prose style) whose role is primarily to gain ‘stature’ (the hierarchical language is obvious) once they have ‘demonstrated their considerable abilities’ to more than just ‘some degree’.[28] I learned from the examples in this beautiful book. What I wanted on top of this was less about the ‘heights’ of ‘Soviet art’ or any other particular niche of academic research and more about interactions between life, history and artistic objectives. At the moment the ‘history of art’ is still about appropriation of human experience by any old hierarchical form of thought and feeling, in short ‘authority’.

All the best

Steve

[1] Jones & Swanson (2020: 242)

[2] ibid: 6

[3] ibid: 62 & 58 respectively.

[4] ibid: 246

[5] ibid: 78, 122 & 192 respectively.

[6] ibid: 160

[7] Virginia Button (2003) Christopher Wood: St. Ives Artists London, Tate Publishing

[8] ibid: 19

[9] Cited ibid: 22

[10] Richard Ingleby (1995: 245) Christopher Wood: An English Painter London, Allison and Busby.

[11] ibid: 252.

[12] Jones & Swanson op.cit.: 110

[13] Ingleby op.cit.: 268

[14] ibid: 268

[15] ibid: 67

[16] Katy Norris (2016: 22) Christopher Wood London and Chichester, Lund Humphries in association with Pallant House Gallery.

[17] Simon Martin (2018:41) ‘Mediating Queerness: Recent Exhibitions at Pallant House Gallery’ in Katz, J., Hufschmidt, I. & Söll, Ä (Eds.) Queer Curating in Notes on Curating Issue 37 (May 2018) Available at www.oncurating.org

[18] ibid.

[19] Norris op.cit.: 144f.

[20] Norris op. cit.: 57

[21] ibid: 67

[22] Andrew Motion (1997: 145) The Lamberts: George, Constant and Kit London, Faber & Faber.

[23] Andrew Motion (1989) The Pale Companion London, Viking

[24] ibid: 146

[25] Best treated in Ingleby op.cit.: 155f.

[26] Steel, Coquet, F. (1997) ‘Postcards and Painting: The Case of Cristopher Wood’ in Cariou & Tooby (Eds.) Christopher Wood: A Painter Between Two Cornwalls St. Ives Tate Gallery Publishing, pp. 20-26.

[27] Button op. cit. 58f. Sleeping fisherman, Ploaré, Brittany 1930 oil on board, The Lain Art Gallet, Newcastle upon tyne.

[28] Jones & Swanson op.cit: 9

4 thoughts on “‘Wood moved freely among Paris’s most elite artistic circles as he experimented with various post-impressionistic styles, bisexuality and opium.’ Does the history of art as a discipline on its own really have the skills, knowledge and values required in order to reflect adequately on the value of shortened lives? Reflecting on the case study of Christopher Wood in Angela S. Jones & Vern G. Swanson (2020) ‘Desperately Young: Artist Who Died in Their Twenties’.”