‘Long ago our bathing was done in natural bodies of water. This gradually changed as we transformed parts of the world to reflect our desires. Bathing rituals, materials, and architectures carry over memories of these places in different ways. the landscapes we bathe in are irreducible to simple forms. Architects of bathing enjoy the constant shifting between environmental readings, and this can make them hard to define. at one moment they appear to be a biologist, then a structural engineer; next a painter or a poet, then a psychologist. They struggle to escape the attraction to formal essentialism and its clichés’.[2] Soaking in the Christie Pearson’s (2020) The Architecture of Bathing: Body, Landscape, Art, Cambridge, Mass. & London, The MIT Press.

I often struggle in blogs to find a quotation that characterises a book that has really excited me and with Pearson’s great book I have failed big time. However, the task here is immense. Hence I have chosen a quotation that illustrates why that task is so formidable in this case. Pearson herself is a factor in this work of enormous import because she is not just a writer in the ordinary sense of the word – she is the subject of a book that is still not autobiography, even less so than Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Autobiographia Literaria which, at least tells the story of its author’s life between its interests in absorbing a way of thinking about and feeling around how to describe the world as he sees it. Pearson is in this book as its subject, at least in part, because she is an ‘architect of bathing’, and this is far less a known typology of the world than the ‘man of letters’. Nor would it help just to point out the gender difference in the contrast here – important as is Pearson’s role as a woman in this book. For this book is intrinsically a feminist project in which women act, feel, think and do much of the revolutionary work of understanding and realising the significance of the world of bathing. Men’s ability to slip into established roles is always psychosocially and environmentally facilitated thing, and is the truth of how patriarchy works so silently and apparently without conflict, and that might help us see how and why Pearson locates herself, the work she does in the external world and inside the book in contexts of conflict, transgression and sometimes palliation for the harm that goes with an agonistic view of the world.[3]

For Pearson does not only show us that the project of genocide that established the current North American status quo (Pearson is Canadian but does not allow Canada off the hook here) happened with evidence that is strictly within her topic – the role of sweat lodges and their active and conscious suppression by violence and legally framed oppression by cultural and racial supremacists, colonists and imperialists in native North American communities. How superb and politically astute is Pearson’s perception that practice so global and enduring that she finds a parallel in the ‘Scythian practice of sweat bathing’ using cannabis infused in steam described by Herodotus in the fifth-century BCE endures by transforming its practices, including architectural practices.[4] Banned by the ‘assimilationist Indian Act of 1867’, the ban on sweat lodges persisted till 1951, and that the effects that this had on their practice are also lost from conventional history based on the norms of the status quo.

When bathing cultures of minority or colonized peoples become suppressed, their traditions must go underground to survive. As contemporary Indigenous people worldwide establish methodologies and frameworks, deeper insights into Indigenous bathing practices will become more accessible.[5]

How wonderful is this. It admits that our current knowledge is partial because that knowledge itself is compromised by power relationships that have yet to find their means of being fully exposed and that the means of understanding reality of the colonizers are still far from being as based on objectivity, whatever that is, as they claim. You have to read on, and between the lines to see that Pearson also actively engaged as an architect in this means of praxis in her ‘years of working as an architect for an Indigenous organization, Native Child and Family Services, in Toronto, who took me to a sweat in 2006’.[6]

Pearson’s account of how this Indigenous group adapted its materials and resources, including by implication human resources such as Pearson herself, tell of a very wonderful life live amidst the realities of the products of political oppression and the means of reclaiming traditions and why this need be done, beyond a mere interest in lost heritages. Because real work often shows that such lost traditions were not so much lost as buried alive by those with an interest in domination.

Pearson digs up much the same kind of stuff by uncovering how bathing practices have articulated oppression and resistance in various elements of an agonistic community – women, queer people and marginalised groups produced by émigré status. There is no embarrassed standing off from these groups – often the rationale for suppression of some bathing practices is, as she shows so lightly, control of issues like gendered power structures, sexuality or expression of affiliation of other kinds including the care and support of children, and cultural practices in the varied legalisation of stimulant chemicals. Hence her placing of the history of queer sexuality in bathing in institutions, because even the transgressions facilitated by naked bathing can be controlled in this way and often was for reasons that suppression was not effective. The origin of single-sex or apartheid bathing has roots in cultural constructs such as purity and fear of contamination but its function has been to compromise with transgressive desire by encoding it in limiting regulations, laws, ideological practices and architectural or temporal segregations. She cites like-minded research on the sociocultural histories of bathing such as Jeff Wiltse’s (2007) Contested Waters: A social History of Swimming Pools in America. His research into the regulation of bathing that crosses ‘barriers’ that law wants actively to reconstruct like those of gender and race and orientation. She cites him thus:

The real issue was interracial intimacy. During the hearings in 1954, city solicitor Edwin Harlan argued that racial segregation must continue in swimming pools … Harlan predicted that whites would riot if black men were permitted to swim with white women.[7]

Thus some of the roles that Pearson takes on in order to author this book are easily shown but the deep connections between them are harder to articulate and established by Pearson only because her book is constructed so beautifully. Thus it genuinely convinces us that it understands why biology, engineering and architectural building (social or physical), poetry, visual art and psychology (I would add sociology here to the mix) are so, in the end, integral to truth and why they do not alone address the ‘essences’ they pretend to address but rather temporary constructs that convenience their own maintenance as powerful knowledge bases.

How, one might ask, does biology enter the mix?[8] The book’s subtitle is not that empty show of verbiage that they often are in more, usually solely academic, texts, apart from the rather bookselling substitution as third term of the three of ‘Art’ for ‘Practices’. For this book deals with art as yet another practice or praxis, as indeed it is unless one has a highly hierarchical view of the world to defend. The Book is sectioned so that it begins with ‘how bathing addresses the human body as both singular and collective’.[9] The middle term ‘landscape’ stays as it is since it will show how environmental features – natural and built or hard to contra-distinguish – provide us with terms of later analysis of human praxis.

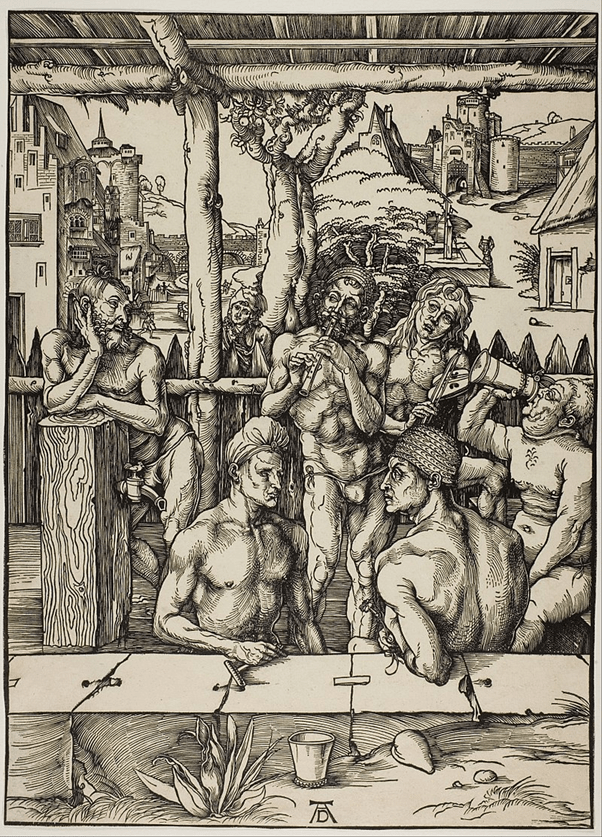

Concepts of the body often exclude the social body, for which Pearson correctly blames the kind of art historical tradition represented by Kenneth Clark and his hierarchical notion of the body as either a sublime nude or as grittily reduced to the naked (follow the link if you want a more sympathetic take on Clark). Against that perspective Pearson sets some thought heavily influenced by feminism from Linda Nochlin and Sylvia Sleigh, whose work lends itself to seeing the link between various groups ideologically oppressed under the name of ART or ART HISTORY.[10] The biology used here links intrapersonal body qualities with interpersonal and social ones. How for instance is an interest in the states of physical fluidity and relative stability of water (the major component of the body as we are told here) perceived by both kinds of body and how and where does this implicate nudity or nakedness? How can we theorise the interaction between senses such as hearing, sight and the haptic (to name but three) without prioritising the old hierarchical status of vision over the others? How is form, in different kinds of profile including temporal ones, sensed by the body.

There is considerable stress on the haptic in the book but not just as touch senses to the hand but also to the skin conceived as a sense organ. The feel of water in any form or at any temperature above or below the norms of blood heat, for instance, on the skin is throughout – and often described as ‘silky’. The concept of the porosity of the skin will be central to this argument because the skin is only a barrier if we exclude these modes of access and egress at the pores – in which fluids are exchanged in bathing including sweat (in sweat lodges) and vapours (in steam or other vapour baths). The fluid water of a pool or pond will only complement a body that is more fluid than we like to think and which extends to other organic body excretions. Whereas water might be used to exemplify ‘purity’, worlds of living decay can be captured in stinking mud, whether captured in Rauschenberg’s (1968-71) Mud Muse installation or a South Korean mud festival. Mud might be complemented in some rituals by rotting organic matter.[11] Sometimes the insides and outsides of the body are seemingly inverted in the sensation at the pores:

When I emerge, my skin is pulsating, vibrating with circulation. my blood and heart become palpable. I am inside out … The lining of my nostrils expands, and I am breathing like a mammal and a fish at the same time, diffusion happening across the membrane. An old kind of breathing.

ibid: 118

The immersion of the body in bathing also plays around a sliding scale between binaries that Mary Douglas tells us that ‘civilisation’ attempts to keep entirely separated from each other: purity and dirt.[12] Yet water as we actually contact it often is a ‘messy mingling of vegetable, animal and mineral’.[13] The sense organ truly addressed by bathing is the skin and its quality of porosity which is addressed not only by touch sense receptors but temperature receptors. Porosity might mean we ingest too through the skin, though we might use the term absorption.[14] Hence the play in bathing rituals with sometimes extremes of temperature which Pearson illustrates uses flow charts to show the process to be accommodated by the enveloping but yet discriminating architecture. Finally in public baths the body becomes communal in what it share with theatre: as Pearson puts it: ‘One of the tasks of architecture is to cultivate environments that support theater (sic.) and ritual as an offering of the community’.[15] It is through theatrical community events and happenings that ritual bridges private experience and public practices: the individual and the social body.

The concepts needed from landscape features in Part 2 of the book meld ritual experience, especially experience of change of status, with bathing practice and concepts of liminality. Thus a waterfall signifies rejuvenation, the sea rhythmic theater, the river flow dynamics, the pool volume contrasts and control, the pond – opacity, reflection and depth. Thus armed with body and landscape terms the practices embodied in the architecture and social experience of different cultural bathing traditions are examined as already seen with the sweat lodge. This examination of practices never fails to show that different cultures appropriate the traditions of other cultures but often too limit them For instance single-sex bathing may have been imposed on some cultures just as more certainly was the emphasis on hygiene and purity of purpose rather than mix and congress in bathing, including sexual congress. The discussion of the gay bathhouse for instance is early in the whole book emphasises its links to the Roman thermae’s or Greek gymnasium’s ‘programmatic use of sex’.[16] Even where sex is seen as a transgression it is ‘one that is embedded in every act of bathing, in its suspension of everyday regulations, bringing with it a sense of underlying danger and guilt, connected to issues of purity, power, and physical difference’.[17] The key allegoric narrative is the death of Actaeon on viewing the goddess Diana naked.[18]

A key point about this book is the way it uses contrasts between the ‘Natural’ and the ‘Artificial’ because it is in this context in particular that essentialism often raises its head. There is no ‘natural’ after all that is not subject to art or craft, even where the effect might be indirect. Artifice as such is addressed directly in Chapter 14 on the Japanese sentō baths and the point is made well here: ‘Bathing environments, like urban environments, contain formal, cultural. and ecological aspects working interdependently’.[19] Of course the same is true of what are known as rural environments, perhaps even more so and the interdependence of what is with practices acting upon it is too complex a network of causation to revive essences like nature and art as opposed forces. However bathing architects can choose to emphasise this interdependence or not as the Termas Geométricas (2009) in Chile emphasises that ‘it is a piece of architectural work located in the midst of wild brutal nature that allows one to be seduced again by primitive elements’.[20] That nature and primitive are part of conceptual as well as practical co-construction seems obvious here.

Likewise some ‘natural’ phenomena looked in the Landscapes section of the book illustrate that there is more than a semantic and conceptual issue in our fascination with some of the base terms of natural landscapes. Especially, given the image of Termas Geométricas I have chosen above the waterfall. When this feature is incorporated architecturally, it is difficult to deal with phenomena that are stable semantically and ontologically. Some waterfalls are more comfortably seen as mere cascades, taps, showers or fountains. Even the waterslide is invited in here, ‘a vertical bath with a twist’ as Pearson says.[21]

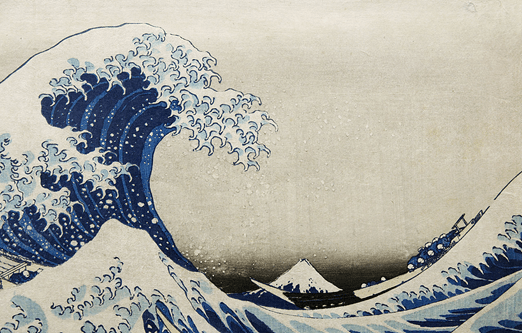

Now, of course, the academic traditions of the West hate some of the slippages into interpretivism and subjective evidence here and elsewhere in the book. I love it precisely because this author is not present as merely an author but a documentary maker of her own practice and that of others, including those who really make architecture a living and transforming thing, the bodies that use it. Lots of witnesses are called and none really are hierarchically graced over others whether they are Hokusai or Virginia Woolf describing waves or a local user of Penzance’s ‘concrete beach’.[22] It all matters and illustrates how what we see and feel ‘flow, time, and emergence’ interpenetrate. Thus Hokusai’s 1829 famous Great Wave Off Kanayama ‘turns in upon itself and completes its promise in an unending form, nearly static, apparently without beginning or end’.[23]

When was it that higher education began to equate learning with teaching as if it were inseparable from learning? When was it that academics work started thinking they had no duty to dialogue, only to monologue whilst jealously guarding copyright and rights of unquestionable authority? It wasn’t thus when I was younger.

Well, here’s a book that does it differently. Christie Pearson is a kind of hero to me and I’d fain call her teacher because she writes as a co-learner.

Steve

[1] Pearson (2020: 331)

[2] ibid: 331

[3] For a cognate interpretation of what an ‘agonistic view of the world might be’ and why it always, at best and outside its right wing destructively fascistic extremes, is a constructive philosophy and politics see Mouffe (2016) Democratic Politics and Conflict: An Agonistic Approach (umich.edu)

[4] Pearson (2020: 359f.)

[5] ibid: 360

[6] ibid: 357f.

[7] Wiltse (2007) cited ibid: 365.

[8] Not in the simplistic forms of binary sex categories which have replaced a serious attention to biology proper in some forms of misnamed radical feminism. Note this: ‘To ignore the impact of sexual difference in the formation of culture and architectures would put us at a disadvantage…; yet to be circumscribed by it leaves us in ill-fitting clothes. the experience of a male-to-female transgendered woman in a women’s public bath reveals the limit of artificial regulation’ (my italics).

[9] ibid: 17

[10] ibid: 228

[11] ibid 302-306.

[12] ibid: 305

[13] ibid: 220

[14] ibid: 305

[15] ibid: 91

[16] ibid: 67ff.

[17] ibid: 369

[18] ibid: 372ff.

[19] ibid: 332

[20] The architect Germán del Sol cited from private correspondence to Pearson, ibid: 340

[21] ibid: 115

[22] ibid: 162- 165.

[23] ibid: 164

5 thoughts on “Struggling ‘to escape the attraction to formal essentialism and its clichés’.[1] Why the world gets oversimplified! Reading as an aid to seeing the world as more whole and more complex than one way of seeing it. Soaking in the Christie Pearson’s (2020) ‘The Architecture of Bathing: Body, Landscape, Art’.”