‘not made with hands’: a shaggy dog shaped reflection on the limits of curation as a model of historical knowledge. A problem in the history of art? A view from a queer retreat. A case study based on reading The Human Touch: Making Art, Leaving Traces by Eleanor Ling, Suzanne Reynolds & Jane Munro, Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum / London. Paul Holberton Publishing.

I’m in a rather melancholy and ruminating mode and hence the ‘shaggy dog story’ shape of these reminiscences and ‘reflections’. I began by thinking about the reasons that make me blog. Near the top once was that retirement had its drawbacks, not least in opening time out into large and empty tracts. I once trained and worked as a Primary Care Graduate Mental Health Worker – a now defunct species – and discussed this very topic with many older people who felt plunged into post-retirement anxiety and depression. Working class elders in particular, more often than you might think, sometimes translated or had translated for them the fact that they lacked the various forms of social and economic capital given in bourgeois retirement such as I now enjoy. They sometimes introjected their feelings of low self-efficacy such that persistent feelings of hopelessness were read as a function of ageing, rather than social injustice and inequality. After all, the social world is organised around symbols of paid employment. Post-retirement anxiety and depression can strike people as if it were the portal to a realm in which those who ‘enter here’ must ‘abandon all hope’.

But maybe there is too much social emphasis on the ‘dark wood’ of middle life: middle-class retirement is based on generous retirement insurance schemes (that are disappearing as fast as neoliberalism enlarges its occupation of the social and economic system) that make themselves look like access to freedom. The only danger here is to think we earned that perceived freedom personally rather than, together with other beneficiaries of mixed economy capitalism, having appropriated it as a result of past investment – including the social investments of the welfare state. I realise I benefitted from socialist education policies after the Second World War now in ways that are not easy to summarise. And yet …. how much inequality remains and how limited the hunger to address it.

Given that sobering inducement to scuttle back into the dark, I realised too that the famed freedoms of retirement, as inequitably distributed as other resources in our lop-sided society, are probably related to no longer having to collude in maintaining the illusion of integrity in the social and economic system that feeds us so unequally. This is one reason why I rejoice at avoiding the stress of versions of teaching and learning that collude with the self-interest of problematic institutions like the zombie university. My last intercourse as a learner with that institution was in attempting to learn about the History of Art. The deadness of a system of teaching and learning, that names itself higher education, is more obvious in that discipline than others as it displaces thought with repeatable structures of dead routine. So much so that in the institution in which I studied it, the essay questions, supposedly at MA level, were never changed lest they challenged teachers to rethink their posture and forget that they only felt to be balancing the demands of teaching and learning because they were being propped up by their unchanging look, whilst the knowledge and skills within were rotting.

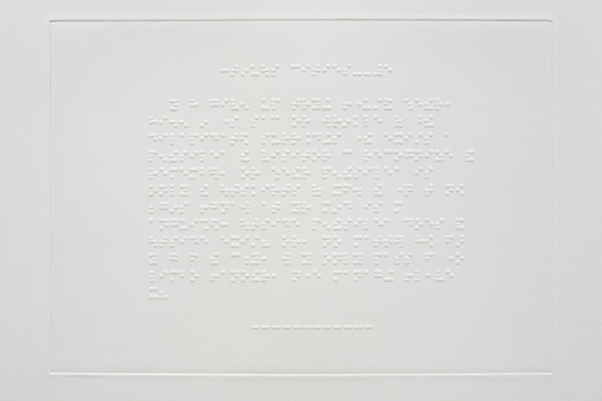

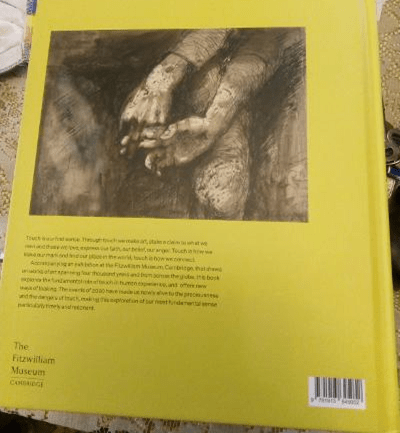

To feed my blogging I prefer then to seek out forms of knowledge curated by agendas that look for relevance to something contemporary without being, as snobs say, ‘modish’. In the practice of teaching and learning about art much has had to change recently. First, as a response to dwindling finances for the supported arts, which have forced public galleries and museums to seek new approaches to their current stocks of items by curating knowledge about them rather differently. This is the case with The Human Touch which as an exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge, it is claimed, was five years in the making, only to be disrupted by a pandemic where touching was suddenly seen as a source primarily of transmission of infection. Not, of course that touching, at least not of objets d’art is a function much served by museum services. Indeed one wonderful exhibit is Jane Dixon’s (2006) Braille Suite.

It consists of five etchings embossed with braille text from a novel by Italo Calvino, and hence not easily ‘visible’ except through touch but encased behind glass in order to ironise this very aspect of the museum’s role in preservation of objects, particularly from supposed damage caused by touching.

The book of the exhibition is however much more a virtual remnant of its intentions and effect on us because of the closure of museums consequent on the Covid-19 pandemic and this fact runs as a symphonic theme of the book’s text, not least in a beautiful new poem by Raymond Antrobus in which a nurse muses:

Now I sit by patients I can’t touch. And I don’t know what to do with my hands.[1]

This is a tremendous book and cannot be praised too highly. Through five chapters it pursues five key themes represented by hands as a visual icon or as referred to in verse, in which most of my own favourites are exampled and brilliantly discussed and/or contextualised such as images from anatomical textbooks, the Keats fragment ‘This living Hand’, Rodin’s hand studies for The Burghers of Calais, and Sutapa Biswas’ Housewives with Steak Knives. New to me was work by RUN and Carmen Mariscal and Richard Mark Rawlins. The theme and human domains illustrated by hands include:

- the anatomical and medical, including its reflection in the art of Barbara Hepworth;

- the hand and skin as organs of the senses including some consideration of the microbiology of nerve receptors;

- the hand as an instrument of work. This is excellent on the finesse associated with hand work and the hand as the organ of hard and blunt labour, with some good use of the origins of the later use (surely the origin of the term ‘hands’ for labourers in Dickens’ Hard Times).

- the hand as a means of communication, especially of claims of possession and emotional bonds or distances,

- The hand as a symbol of power, resistance and, when bound, as powerlessness.

- The hand as an icon of reverence and or destructive creation – the use of hand markings to defy the symbolism of slavery in the treatment of Edward Colston was particularly good.

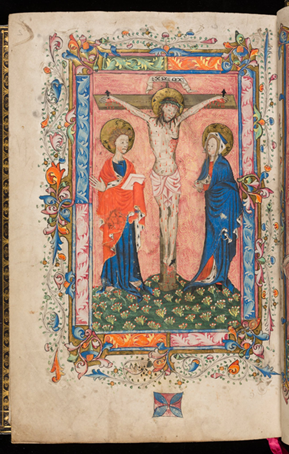

The examples were, in illustration of the economies of modern curation, items held (the hand metaphor is inescapable) and / or owned by the Fitzwilliam itself. As a means then of demonstrating the worth of an archive of objects, including objects marked by paint and text, this raised many surprises for me and made me want to visit this museum again. The display of medieval manuscripts is wonderful, not least the late fifteenth century Fitzwilliam Missal.

As a substitute for a visit to Cambridge, this gorgeous book of well-illustrated essays did me proud and I loved it, though its function is more to collate what is known, as with the best curation, and to interpret in ways that opened up many threads for curious minds to follow than to innovate in knowledge and skills. Perhaps that is all we should or could ever ask for publishing that teaches its readers. I hope to show that more can be given in other books – such as in my next blog on baths and bathing – but a caveat remains that is my main theme, though not to the detriment of the book.

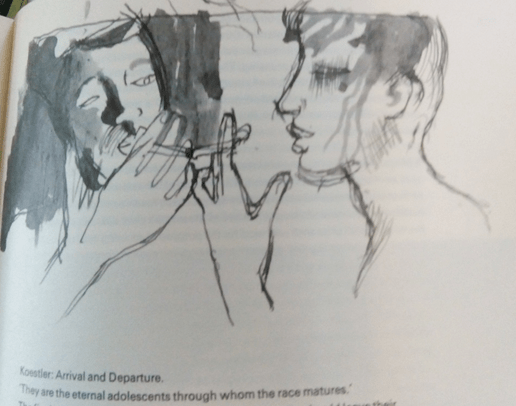

My intention on reading was to look again at hands in graphic and written art to firm up my own ideas about hands in mid twentieth century queer fiction and art but especially the art of john Minton and Keith Vaughan. What I did not know was that a drawing that sparked this interest, selected by Vaughan himself to illustrate his published excerpts from his war-time and thereafter Journal & Drawings existed as an original with correspondence pertaining to it by the artist in the Fitzwilliam. Indeed it uses a reproduction of the Vaughan drawing as its back cover.

Before taking issue with how curation can sometimes misrepresent histories especially queer histories I need to show why the topic comes up at all. Queer novels in the 1930s-50s often used the trope of hands to express a man as an ideal object of desire for other men. there was clearly something in this of trope of an acknowledgement of variations in masculinity where one identity marker for a ‘real man’, as opposed to one compromised by desire for other men. Lots of evidence can be marshalled but it isn’t my purpose to do this here, although it is worth seeing the trope in action in the infamous 1950s queer novel by Rodney Garland wherein the men loved by queer men are marked by their large hands. Moreover having large hands becomes an identity marker not only for pronounced masculinity but also of working class origin, feeing off tropes that manual labour was of a lesser value than intellectual but more characteristic nevertheless of men uncompromised by any kind of passivity as a definition of their working as well as sexual lives. Such men, the myth goes, did not shy from active sex with queer men, provided they were the active and not the passive partner. The ‘type’ can be found in the found too in the diaries and biographies of queer men including John Minton as well as Keith Vaughan.

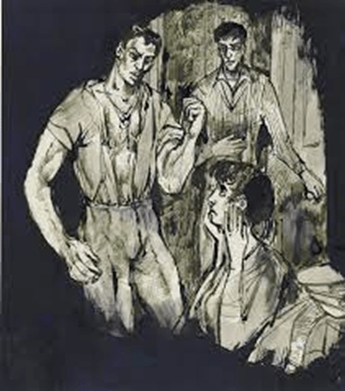

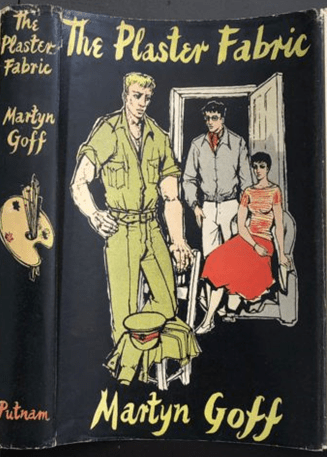

Look for instance at Minton’s dust jacket illustration for queer novels, notably The Plaster Fabric (1957) by Martyn Goff. Minton’s draft design for this cover, once owned by the queer television art critic, Brian Sewell, distinguishes Goff’s working-class guardsman, Tom Beeson, from the queer art student character, Laurie Kingston, by prominent comparison of their hands:

In the final version (below) Tom’s masculinity is no longer tested on the fear he can provoke in Susan and only the hands remain to indicate the real man of the working classes.

Vaughan’s drawing of hands that touch feels very much in this tradition and hence I find the treatment of this drawing problematic, partly because it is examined only in relation to a reconstruction of Vaughan’s intention from a cited letter in the Fitzwilliam collection together with the original drawing. Thus Eleanor Ling writes:

Vaughan claimed that he made the drawing, Study of Hands (1944), after seeing a soldier and ‘his girl’ together. … He wrote that he stared at the couple’s joined hands until the image was committed to memory. The bone structures do indeed appear to be male and female, but Vaughan’s interest in the couple, his admission of intently watching them, and the truncated composition are poignantly suggestive. Vaughan’s upbringing and formative years were those prior to the UK’s Sexual Offences Act, when homosexual acts between men were made legal. … someone constrained to think secretively about romantic touch, or obliged to obscure details of his or her own encounters, might well choose to depict such a reduced detail of two lovers, producing other, more socially acceptable moments of touch, ‘expressing something essentially human’.[2]

Now this uses evidence from a private letter appropriately to interpret a single drawing, but in my view, it makes unnecessary assumptions about Vaughan and queer life before 1967 all built on a belief that artistic products necessarily express subjects in consonance with the law and what is ‘socially acceptable’. Yet it seems to me that that the extrapolation from the letter of a belief that this picture is heterosexual in content, despite Vaughan’s wishes and because of his own fear is inappropriate. Since I have not seen the letter referred to Malcom Cormack on 25th March 1967 I cannot comment on interpretation but I think we need to stress that the letter is not contemporary to the drawing and appears to be, given its recipient, to be that which accompanied the gift of the drawing to the Fitzwilliam’s renowned curator. By March 1967 there was no need to hide any queer content one might think.

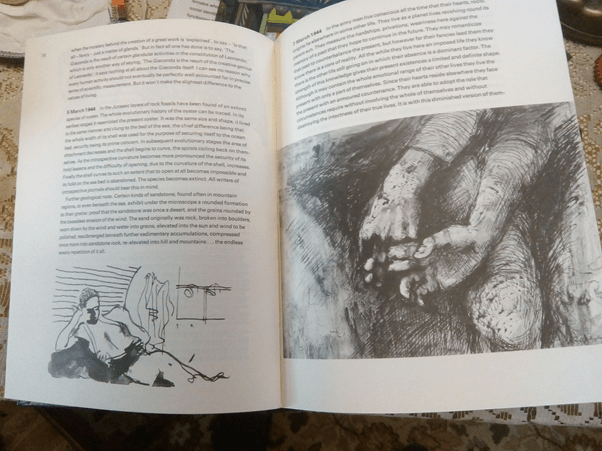

Moreover this drawing has been a favourite of mine since seeing it as one Vaughan himself selected to accompany the first publication of Journals and Drawings in 1950, & years before the publication of the Wolfenden report (1957) to say nothing of the ten years that followed before its recommendations were turned into law in the Sexual Offences Act 1967.

The drawing appears on page 79 alongside text from the Journal referring to 7 March 1944, which discusses how married heterosexual soldiers form inside the camp, ‘all contacts, friendships, love affairs’.[3] The implication is clear. Heterosexual men can form contacts, friendships and love affairs without compromise of their heterosexual marriages because they do not need to ‘involve the whole of themselves’. I do not see male and female bone structures in the picture moreover, although I can see how the artist might want to comfort an august art historian such as Cormack that he could if he wished. It strikes me anyway that there is too little evidence of bone structure here, which is anyway not always decisive. What I sense is how art history twists a story to avoid any contact with a suppressed queer history, which is considered irrelevant to the artwork.

Vaughan’s fascination with masculine sexual behaviour is discussed frankly in 1950 in ways that would surprise Eleanor Ling if she really believes the history of queer men lives she invents in this book to fit an appropriate art historical model. For instance, his paintings often deal with ways in which men could engage each other in ways that were not obvious to an outside view. One such scenario was the sharing of the lighting of a cigarette, as in this example from one page opening before the Study of Hands:

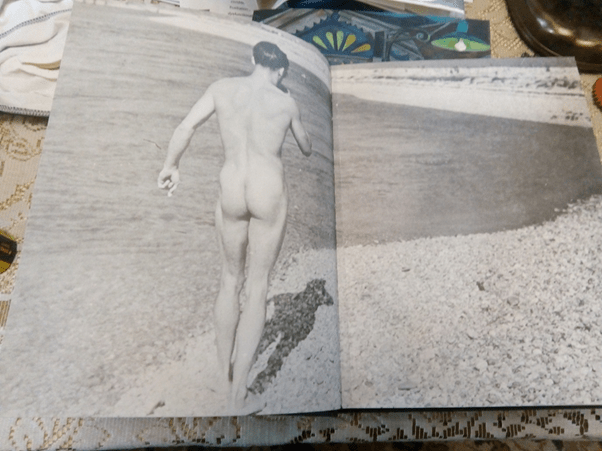

The progress of sexual desire between men is not hidden but it may be occulted, which was actually the effect of illegality and mores that were far from being shared by all. Vaughan’s Journals and Drawings reproduces Vaughan’s own photographs of naked young men at Pagham Beach from 1939 and later with the all-male bathing pools of Hampstead Heath. There is no need to reference Vaughan’s erotica from the 1970s to show that he could draw queer content.

There is therefore a severe limitation in the substitution of a curation of owned art as a substitute for contextual history, especially when that history is suppressed. Because Ling’s conclusion, though well-intentioned, clearly reinforce the notion of the queer man as victim, in line with the representation of him in Wolfenden, heteronormative stereotypes and countless other ideological forms. By now we need more. Especially from books that are excellent and beautiful otherwise.

All the best

Steve

[1] Raymond Antrobus ll. 19ff. ‘On Touch’ in Ling et. al. (2021: 35)

[2] Eleanor Ling (2021: 93) ‘Taking Hold: Communication, Possession, Emotion’ in Ling et.al. op.cit.

[3] Vaughan (1950: 79f.)

5 thoughts on “‘not made with hands’: a shaggy dog shaped reflection on the limits of curation as a model of historical knowledge. A QUEER problem in the history of art? Based on reading ‘The Human Touch: Making Art, Leaving Traces’ by E.Ling, S. Reynolds & J. Munro.”