‘… all the lights in the Quonset hut were on but it was empty. The men were either at the movies or in town. Stephen felt both disappointed and relieved that there was no one there with whom to share his experience. … It was like leading a double life’.[1] ‘… Raven has the body of a man. That’s to show his double nature. But so would Loon, I guess, if he were Raven’.[2] Reflections on identity in a 1960s queer novel in the USA: a case study on Totempole (1966) London, Anthony Blond Ltd.: Lost Voices and the Queer Novel 4

Reading this queer novel from the USA is a kind of culture shock for a queer man who grew up in 1960s Britain. It certainly isn’t because the American queer novel was a new phenomenon in writing or new to this reader. In the modern novel, it is predated by Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar (1948), and James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room (1956) to say nothing of earlier American novels that followed the austere Platonism of Bayard Taylor’s version of male affiliation in the nineteenth century.

However Sanford Friedman’s novel stuns precisely because, though pioneering in many ways, it facilitates a genuinely ironic reflection on the way an identity was being carved out for gay men. It provides all the ammunition to allow us to see limitations in building this kind of single psychosocial identity as well as strengths. Read now, it still actively, and very enjoyably in my view, overturns tropes about gay male identity I identified with through my own personal history from British culture and returns queerness to one item amongst others of the sense of the intersectionality of identity. Amongst such intersectional experience, of sometimes complementary and sometimes antagonistic ‘identity’, expressions of single-sex love or desire sit with other equally important facets of potential self from an amalgam of our socio-cultural and personal experience or social cognition, including but not leading with biogenetic, histories. As a novel, it faced a problem shelved by Baldwin, that otherwise greatest of USA queer black radical writers, who still amazes first-time readers by the fact that his gay male novel takes a white man as its centre of queer sexual consciousness. We are amazed of course at precisely the depth to which racist oppression penetrated. But it is not just that Friedman explores masculinity and a developing sense of queer desire in his hero Stephen at the same time as the contributions (strengths and limits) of white Jewish family and individual identity but that the latter too must take its place in the mix of intersectional being, and is eventually one of many experienced selves.

But before looking at this (and central importance of the central symbol of the Totem Pole) I wanted to face straight one central myth of queer life that is at the ironic heart of this novel, whose true enemy are the binary oppositions which support identity politics (white / non-white, man / woman, Jew / Gentile, and straight / gay). The attack on binaries is necessitated in part because a historical accident of queer life (probably confined to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries) has spawned the literary trope of the ‘double life’ (in which a queer consciousness must negotiate the binaries of authentic and non-authentic life, queer or normal) through rituals involved in ‘passing’ as an example of the norm or ‘coming out’. Such rituals can sometimes feel oppressive – as Stephen feels the experience of his bar mitzvah is both in terms of an expression of racial and gender identity, ‘a ceremony to celebrate his coming to manhood’.[3] Now I don’t want to belittle the necessity of ‘coming out’ as ritual expression here but merely to emphasise that it carries limitations to consciousness in posing the choices facing young (or even older) people as one or the other not a greater range of choices and priorities amongst a multitude of the actual ones, in which sex/gender, class, race, status markers and so on are all included.

Let us take one very powerful binary trope from the discussion of queer identity – that of the ‘double life’. In the first quotation I give which ends that it was ‘like living a double life’, we might expect that it refers to Stephen’s ongoing re-discovery and ownership of his life as someone who both loves and desires men. In fact it refers to his discovery of his skill as a teacher and bridge to the culture and marginalised prisoner status of his Korean anti-Communist interns. Friedman feels sure enough of the game he is playing with readers accustomed to reading and seeing examples of queer double lives that he rather sexualises the experience he intends to describe. Stephen is ‘overheated and excited’, unsure of his ‘balance’ as he feels his body sweat evaporate ‘in the night’ and connect him to the actions of his ‘breath, nerves, heart’. The atmosphere itself is ‘turbid, swollen, overbearing’, as if playing at sexual games around him.

Once back in the Quonset hut, the absence of specifically male company is noticed with regret but, at the same time, celebrated. The desire to ‘share the experience’ is always thus ambiguous when the reception of one’s experience (whatever that experience is) might be negative, ambivalent or null because it is not publicly acknowledged as a valid experience by your audience, for whatever reason (be it ignorance, prejudice or role-playing). For me, the learning here is that novel engages us with the fact that we all live a ‘double life’ all the time and around multiple experiences (so much so that a binary term like ‘double’ is ironic and inaccurate) – not just around queer sexual experiences.[4] Of course later sexual desire and its bodily fulfilment between men will be a feature of Stephen’s knowledge of his Korean friends: particularly Sun Bo, a Korean man who ‘wasn’t even queer’ and ‘under normal conditions’ would not be choosing to dance (or have sex) with men.[5]

The theme of the ‘double life’ is there throughout, even in Stephen’s experience of being cared for by Clarry, a black servant unknown to his racist parents who call her schwartze, a derogatory term specific to American (and especially former German) Jewish people, and ‘the thought of smell’ of whose room, ‘turned [his white mother’s] stomach’.[6] As a child Stephen learns, from Clara ironically not his mother, as he contemplates the identity labels ascribed to him on a ‘name tape’ why: ‘It wouldn’t do to have jus’ one’. She says you need two at least but illustrates that more than two are actually required even to cover genetic identity markers. Of course, the most important instance of ‘double life’ is indicated by the Totem Pole, which plays such an important symbolic and narrative part in the novel. This is associated with the awakening of Stephen’s love for, and appreciation of the beauty of, Uncle Hank who share great intimacy: Uncle Hank will ‘discuss intimate, private, painful subjects’ such as the paradoxical pleasure he still derives from ‘the way it feels’ when bed-wetting, for instance.[7] Hank takes on the role of object of love and naïve sexual admiration held previously by Stephen’s father.

He was almost as tall as Daddy and just as good-looking, but altogether different – much, much younger, stockier, not bald. There was something untamed about Uncle Hank; something … that made him seem savage. And yet he wasn’t. … Somehow you could sense his strength without his giving any demonstration of it … “Uncle Hank,” Stephen confided, “I’m awful glad you’re in the bunk next to mine.”

Stephen first confronts the totem pole that will be carved into by Hank and himself amidst this excitement of the new proximity to a strong but sensitive man mentioned above. It is a ‘huge, stripped white pine in the clearing behind the Lodge’ about which Stephen ‘became excited … without knowing what it was or that it bore any relationship to Uncle Hank’. Confronted first then as an easily recognisable and nervously exciting phallic symbol, this pole will take on many meanings – ambiguous double identities in multiple forms that refuse to ever stay binary, not least because all the traditional identity markers of the character set of the traditional Native American totem pole (some are seen on the book cover below) are continually shifted onto whatever item that Stephen identifies with next.

Yet even in native American myth these characters and god start off as ‘double’ at the very least: ‘… Raven has the body of a man. That’s to show his double nature. But so would Loon, I guess, if he were Raven’.[8]

This playing fast and loose with a base of myth in a culture shared by neither character involved, except by a shared inherited of history historical appropriation of that culture in a dim ancestral past, is characteristic. And the base myth of the novel – the passage between human and animal characteristics, which affords this novel its chapter titles (‘Horsie’, ‘Salamander, ‘Loon’, ‘Moose’, ‘Monkeys’, ‘Lice’ and ‘Rats’) and which also connate different stages in sexual development: notably self-stimulated orgasm and masturbation in the ‘Monkeys’ chapter, and which will animate the novel in the sublimated role of the toy Oscar II until Stephen’s final release from reliance on self alone in the last chapter. The notion of metamorphosis into different animals (that are themselves often of unstable identity and at least ‘double’) is a convenient idea for showing how basic, and necessarily multiple, are the roles which manifest complex identity across a biopsychosocial terrain.

That these terrains can cover identity markers from inherited and appropriated cultures is a very important feature of this novel which starts by dealing with a displaced German Jewish émigré family and ends in a Korea about which many myths are shared in the novel itself that transgress a number of boundaries. These include the labelling of racial cultures in words like ‘gooks’ but also in the application of animal labels to show negativity to a group, as in the exploration of ‘rat’ stereotypies in the final chapter. I have mentioned the treatment of Jewish culture but, for the purposes of charting Stephen’s development sexually and ethically, he often mixes attributed roles from different religious cultures. For instance, having ‘finished with’ reading books of the old Testament (the Jewish Covenant that is) that he identifies with the prototype autobiography of Christianity – The Confessions of St. Augustine. to feed his ascetic distaste for a sexual congress with the charming Lenny, that Stephen associates entirely with the life-cycle of pubic lice which he equates with Augustine’s memory of the fact that in Carthage, ‘there sang all around me in my ears a caldron (sic.) of unholy loves’.[9]

This does not stop Stephen however from playing with other roles, particularly of sexually attractive young men – though he rejects Roman Antinoüs (a slave beloved by and deified by Emperor Hadrian), he chooses Greek Hippolytus (a horsey aristocratic character loved by Neptune and thus recalling the infant Steven’s sensual flirtation with Ocean in the first chapter). Standing ‘in front of the mirror admiring himself and striking tragic poses’, is one thing.[10] However, it is clearly doubled and further multiplied by the hubristic saintly roles he also plays from his reading of divines, mystics and poets (‘Meister Eckhart, Hopkins, Tagore, Pascal, Cardinal Newman, Swedenborg, and St. John of the Cross’).[11]

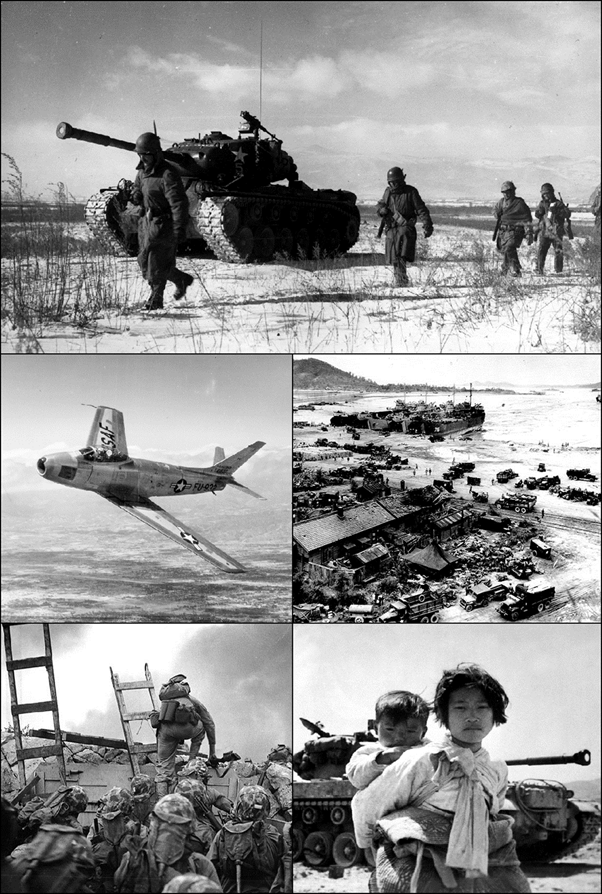

Of course the crux of the novel and that most often remembered is its final chapter set in the Korean War and variously reinforcing through the example of responses to rats the learning that our fears, prejudices and wishes, and the shaping of our bodies by the nervous system that enacts them and which distributes pain, pleasure and the difference between them. This novel must have made many queer men begin to revise their views about how their sexual preferences, even down to matters of the detail of bodies and how they are actively offered or received in loving relationships are actually supported by ideas, including the ideas that shape and value our own identities. Stephen, for instance, must confront the common male fear that their own sexual organs are smaller and more inadequate than other men. Sun Bo explains that this fear and behaviours like needing the light turning out before sexual contact with another man lies in failure to accept oneself – not one’s sexual identity as such but the validity of the current needs of the body as opposed to some idea of the consistency to some particular single identity:

“…If you have shame of the body, if you say, face is beautiful but body ugly – organ understand (very, very sensitive), organ feel despise and disappear. This”, Sun Bo said, indicating his penis, “and this,” he added, touching his temple, “are not separate, cannot be. This and this are unity, like night and day, sun and moon: there is strife, there is war, like here, like in Korea.”… “Stephen also in partition. …”

This uses the binaries of opposites to illustrate duality but, as we have seen, such binaries themselves yield to greater division. For me, the novel is about putting the experiential self beyond the ideas which equate with norms. This will apply too to the treatment of whether one is sexually active or passive and Sun Bo insists whether one experiences sexual pain or pleasure:

Night by night he scrutinised Sun Bo’s responses. Often they seemed more intense, more extreme than his own, but Stephen had no way of knowing for certain, no empirical evidence. the only way of proving it, he finally decided, was to experience the “passive role” himself. … And yet, in some ways, it was more than curiosity. now he absolutely longed for that which just the week before had most repulsed and frightened him – he longed to take the “woman’s role,” to feel Sun Bo fulfilled inside of him, to take as totally as he had given.[12]

The dependence of emotion, sensation and cognition on each other could not be more fully explained, and with it the questions that enable queered sexuality and the transfer of experience into sensation as a way of exploring the multiplicity of roles in and of the body. And this need to tell the truth about queer experience and not avoid the difficult questions is unlike any other mid twentieth-century novel in the genre I know. Rather than bolster pride in identity, it bolsters pride in flexibility of response to the other at the level of attitudinal ideas, emotions, sensation and does not allow self-cognitions, such as are a necessity of say pride in identity to get in the way. I do not know how much the characterisation of Korean male experience is, since this is a source in the novel of overwhelming wisdom about the body and self but symbolically it feels right.

I suspect however, that the novel is too kind to the imperialist ideologies that fuelled the Korean War and too ideological in its assumption that freedom in thought, the body and emotion is dependent on blind hatred of Communism, or indeed any challenge to capitalism beyond that offered by opposition to the Republican Dwight Eisenhower by Democrat Adlai Stevenson as a means of supporting wider social justice. The failure of Stevenson to be elected against Eisenhower is given much coverage and the anti-Communist Sun Bo persuades Stephen to be content in that just as in the new sexual roles that Stephen learns from his acceptance of queered norms. This is an irrecoverable part of the novel’s ideology. Indeed, I am fairly sure I wouldn’t want to recover that purpose in it. However, as a novel about queer life it has a great deal to offer and much comfort to give to those who do not choose above all other aims in their live a desire to ‘fit in’ with the status quo.

I welcome feedback and discussion.

All the best

Steve

APPENDIX from New York Times – a contemporary review (made deliberately unreadable by NYT because it is otherwise only available behind a paywall).

[1] Friedman (1966:333).

[2] ibid: 108.

[3] ibid: 203

[4] ibid: 332f.

[5] ibid: 364f.

[6] ibid: 71. For Schwarze see Urban Dictionary: schwartze

[7] ibid: 101f.

[8] ibid: 108.

[9] ibid: 275

[10] ibid: 279

[11] ibid: 277

[12] ibid: 375