‘ … painting as something that happens to a man working in a room, alone with his actions, his ideas, and perhaps his model. … he seems to me to be the sole coherent unit’.[1] Figure and Body made out of a whole background of Paint. Reflecting on the radical and broken nature of figurative art in defiance of abstraction and form In Bacon, Auerbach and others. Prompted by the All Too Human exhibition in Tate Britain in 2018 and subsequent reflections.

Revised 05/03/2021

Before you read this, I quote here the last paragraph which gives some sense of its experimental nature. It can act as a caveat for more cautious readers who want to read what gives clear answers or asks clear questions: Because I don’t think I do. But this piece is very much me. It explores why I still care about knowing at all.

Here it is:

I have puzzled over this piece a long time and, as with all I write, it says too much and yet not enough. But it points to places I think are worth reflecting upon. That the artist tries to make figures out of an area of paint is the sole coherent action in modernity where it does not aestheticize the art object as its sole interest. It is where figurative art tries to imagine the human in modern contexts where the meaning of what it is to be human may be forbidden, lost or hidden. This is even more so for queer artists who see analogies between the necessity to them of a fascination with appearances and the questions necessary to ask self and environment where the codes of relating have become less knowable – queered because they apply to conditions that are symbolically excluded from ‘normal’ environments.

If you are still with me, let’s begin:

I have chosen one particular (and partial) description of the process of painting by Frank Auerbach in my title largely because it is such a vague evocation of process. It therefore lends itself to a generalised look at practice over a wide range of twentieth-century figurative artists, a range no greater (with the exception of the often ignored Keith Vaughan) than that displayed in the Tate’s 2018 exhibition All Too Human. My selection of painters and paintings to compare can thus come from very radically different works that nevertheless have commonality at the level of such a vague process-based conception. The only works excluded are ones that are explicitly formal and abstract and which, as a result, have no overt representational function at the level say of concepts like the figure, the body or face. In those exceptions paint covering all or part of the surface of a picture is not ever distinguished in terms say of a distinction between figure(s) and its background but only by internal relationship of shapes and relationship of these shapes to their outer framing. The main reason I wanted to write on this topic is my very recent reflections on Francis Bacon in the light of a new biography, about which I have already blogged. One of these blogs was (roughly) on the queer content of Bacon’s life and art and the other on the reception of Bacon’s painting in the verbal art of two contemporary poets. Whilst both feed into the thought process here, my main prompt was the continued insistence throughout Stevens and Swan’s (2021) biography that Bacon continually reinvented his art as a response to the issue of what it meant to be a figurative artist. In my view, there is no more important question in relation to the continuing relevance of art in the world.

To start off, I want apply Auerbach’s statement, or (more strictly) my interpretation of it, to a 1956 painting by Bacon, Figure in a Mountain Landscape .[2] However, this is but a first step before looking at how painters as different from both Auerbach and Bacon and each other as Walter Sickert, and Lucian Freud might also be addressed through similar ideas about the nature of the artistic process. Speaking to David Sylvester (DS) about his preference for Cézanne as a landscape painter rather than as a painter of figures, Bacon (FB) agreed nevertheless with Sylvester’s assertion that, despite this: ‘the figures say more’ to Bacon. The interview continues:

DS: What is it that made you paint a number of landscapes at one time?

FB: Inability to do the figure.[3]

Of course Bacon rarely took even his own answers to interview questions seriously, so we need not be over-exercised by the authoritativeness of his admission of failure here. Stevens and Swan chart the transitions in Bacon’s experimentations with the figure (human, animal or a transitional type between the two) in art throughout his life and convey brilliantly the central nature of what Bacon meant by ‘the figure’ in art as he thought it must come to be.

Throughout his career Bacon created figurative art that, to many witnesses captured a ‘figureless figure’ and Stevens and Swann use this term in the index to their biography to collate such references. Thus, in referring to the ‘artificial landscapes that do not contain a figure’ of the late 1970s, they say that ‘each was haunted by a figural feeling’. This exercise in creating spectral presence matches many earlier versions of the ‘figureless figure’ however.[4] Sometimes this is related to ideas and perhaps even influences from other domains that have been used to interpret Bacon, such as reference to the idea of ectoplasm in spiritualism. The trope of spiritualism allows another way for an artist to compromise the body’s conventional boundaries. However, Bacon impressed other artists, such as Louis le Brocquy, with its capture of ‘sheer presence’, which: ‘”reflected the person who wasn’t in it”. A figure without the figure?’.[5]

As Stevens and Swann go on to show from thei summation here and quite brilliantly, this phenomenon in art was also seeking a theoretician and why not the American, James Thrall Soby, who was to appear (on the basis of After Picasso published in 1935) to other figurative painters of the time than Bacon (such as John Minton) to be a highly significant voice in articulating an alternative theoretical basis for modernism. Soby’s historical analysis was based more on the distortions of figure in European Neo-Romanticism and Surrealism than that of the champions of abstract art such as Clement Greenberg (also in the USA).

Bacon’s answer to Sylvester’s question about landscape and figures in art may therefore be more meaningful than it appears. This answer is usually interpreted as yet another instance of the Bacon smoke-screen wherein Bacon is thought to have created the figures he did only because he could not draw in the academic manner taught in the art schools. In fact the answer may be saying something about the way in which ‘the figure’ as a conception of human personhood is, as a general condition of post-religious modernity, no longer easy to conceive, let alone ‘do’. Thus for our painting. Auerbach knew when he said what he did that people looked to art for coherence, either in the formal design of the whole painting or in the visible coherence of the relation of painted human, animal or inanimate (‘still life’) figures to painted backgrounds. And such a coherence required lines that demarcated the domains represented in a picture, even if in the former case that line was only that of the picture frame itself.

But look again at Bacon’s Figure in a Mountain Landscape. It takes time to see (or make out, to use the deliberate ambiguity in my title) the ‘human figure’ in it, although most witnesses do see it and, more importantly see the same central human figure. However, even this evidence does not stop us from seeing that the picture is also haunted by other potential presences (and indeed figures). Two of these figures are linked by painted marks that are clearly not representational of things (lines of white shaded by black). They unite the seeable vertical human figure slightly to the viewer’s left of the composition with something less human that may be descending, with some effect of speed created, from the top (viewer’s) right. I also notice suppressed iconic faces and body parts (or their ghostly symbols). There are frontal facial features like eyes, mouth and nose, for instance, or in profile in the ‘rock’.[6] One reason we find little coherence in such a picture of obvious marks – dabs, impasto strokes and so on – is the stress on what in Titian (at least) would be seen as characteristics of the ‘colore’ rather than ‘desegno’ paradigm – a preference for paint applied in coloured marks, often in layers that overlap, rather than within easily demarcated lines that constitute the boundary of things in relation to each other.

We know that Bacon supported the National Gallery’s purchase of Titian’s The Death of Actaeon and had, as Catherine Lampert puts it; ‘voiced his intense identification with Titian’s tragic late work. … he highlights the wild erotic fantasy, “the tearing of the human image to bits”’.[7] Whilst it is usual to identify this perception of Bacon’s as a prompt to the psychoanalytic critical interpretation of sadomasochism in his painting, Lampert insists that Bacon’s fascination with late Titian methods, as she sees it through the lens offered by Auerbach as an artistic peer of Bacon’s, has another purpose. The materiality of the paint and its apllication in these extended interpretations best any attempt to represent the figure as a whole. Instead paint skin and volume directly appeals to the same sensation offered by visceral and freshly-torn body parts, especially the wounded skin. The skin is after all a supposed boundary line of the plastic figure. Yet skin is too often pierced, fragmented and enseamed by layers of bodily fluids to be signified merely by the volume, surfaces and varying depths of the material used in the act of performing its signification by accidental or purposive violence from self or others. Paint is a material made up of skins and suppressed flow. The feel and look of Bacon paintings is conjunct with the sensation of reimaigining oil paint applied with and by the body, and still showing the signs of its methods of application. For both Bacon and Titian the body was often itself the instrument of application and Titian experts look for signs of his finger marks in the late paintings. Lampert insists that what was of interest in Titian for Auerbach (and I would argue that this is so for Bacon too) was that it showed, “The aim of painting …:TO CAPTURE A RAW SENSATION FOR ART ”.[8]

Jodi Cranston, a Renaissance art historian, has argued that this in fact, is not unlike what we ought to imagine Titian doing in his late work, sacrificing the clarity of image for the materiality of sensation recaptured from looking that links to the originating performance of painting from the materiality of the body in action and interaction. Viewers thus re-experience mutually with the painting’s subject (Marsyas or Actaeon) sensations that are usually only felt when the body’s boundaries are at threat or promise of dissolution in pain or pleasure, in violence or sexual pleasure. And the point is, she insists, that Titian’s interest was not the sex or violence of the scene, in The Flaying of Marsyas for example, but on making ‘painting visualize precisely this shift away from the fantasy of pure visuality’ by showing how marginal figures in a painting are, as if instructing the viewer of art, ‘looking too closely at other figures, as if seeing beyond the visible’.[9]

Although I range too widely above over interests of my own that merge with those of Bacon and Auerbach, I think the excursion into Titian’s practice and the possible meanings that had for modern painters is still valid. It is not only that Bacon was fascinated by the decomposition of the human body in sex and violence but that he felt that the figure could not be represented other than in its decomposition from social and individual cognitions that pass for thought about the nature of the embodied, This latter ‘thoughts’ may be conceived as of divine origin (the Word made flesh) or otherwise ordained. The authority of art schools for instance sometimes insisted, despite evidence, that the body must be reproduced as a whole, summarised in a bounded delineated form to the eye alone and simultaneously idealised. Bacon’s bodies are not only the sensations of bodies (to the nervous system as Bacon insisted and therefore only truly accessible from admixture of senses – including touch and smell) but a thing to which we do not know either the conceptual limits. Bodies in modernity are objects that cannot so easily (despite false appearances) be separated or delimited from their contexts, environment or multiple reflections of themselves (hence the use of mirrors and portraits in Bacon’s art of the figure).

So if we return now to the Bacon (1956) Figure in a Mountain Landscape, I will again insist that it illustrates Auerbach’s insistence on seeing a lack of coherence in this picture if not in the artistic process. All we see is what we ‘make out’ as we gaze into the mess of painted marks that eradicate the boundary lines through which we are usually offered in classical art distinct whole figures against a background. Instead the figure has become nearly as one with represented contexts and the media of their representation. The issue of foreground and background becomes necessarily problematic therefore. Our sense of surface and depth similarly suffers though we may yearn to see in the picture a man against the background of abutting rocks and recessive caves, there is no certainty about the meanings of the black and darker patches here – of their exteriority so to speak. There are obvious daubs of black, out of which we want to ‘make out’ cavernous interiors. It’s difficult to avoid the illusory language of surface and depth when speaking of art but modernity forces us to see that depth may be is a fiction created by material paint, a black scar and wounds on its surface.

Andrew Brighton interprets Auerbach’s quotation, the one I cite in my title and long ago above, rather differently. He sees in Auerbach representating himself as an ‘authentic self’ that is created in the painting.[10] The ‘sole coherent unit’ Auerbach actually refers to does not feel sufficient to justify seeing this as the artist claiming for himself, as Brighton extrapolates it, as, ‘the heroic painter, who rejects the loss of integrity inherent in the bad faith of social and institutional expectations’. This is to overinterpret I think the debt to Nietzsche in both Auerbach and Bacon. Overarching doubt is all, in fact, that I think Bacon took from Nietzsche. I prefer Bacon’s insistence that sometimes one degrades the human, considered as a number of marks of paint on a canvas, into a ‘landscape’ when the realities of modern life means that no artist can now ‘do figures’.

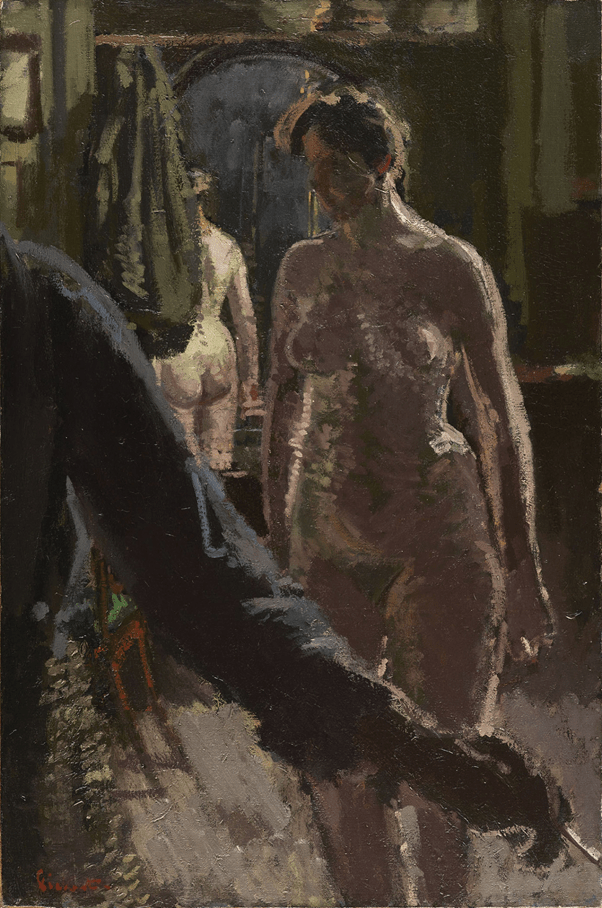

Before returning to Bacon, let’s see how that applies to Auerbach’s own artistic process in say, a picture from the same exhibition, Head of Jake (1997) and to look at how such a process sits with the practice of a known predecessors: Walter Sickert.[11]

Looking at the above pictures together will enable any viewer to find the commonalities, although they differ otherwise in conception and design. Martin Hammer has brilliantly described a line of influence between Auerbach and his predecessor thus:

The sheer presence of paint in Sickert becomes hugely magnified in Auerbach’s thickly worked pictures, which also extend and intensify Sickert’s essentially tonal use of browns and ochres, and his preference for extreme contrasts of light and shadow. At the same time, Sickert was one point of reference for Auerbach’s ambition to fuse visceral painterly surface, evoking the massive substance of external reality, with rigorous, often geometric pictorial architecture and with the evocation of immaterial sensations of light (my italics).[12]

Whilst this captures much in the contrast and similarity of the two pictures, I find it a too easy confluence of the influence of the French Impressionists had on Sickert and the latter’s more limited influence on Auerbach. For instance, I find the dual use of the verb ‘to evoke’ (italicised in my citation of this passage) unhelpful in that in both cases it locates influence as a transmission of the representational functions of Impression, whether what is represented is material reality or ‘immaterial sensation’. Of course, Sickert may well have thought in these terms when painting The Studio in 1906 but I find that an imprecise basis of comparison of the very different line of influence between Sickert and Auerbach. On the other hand the vitally material idea of the ‘sheer presence of paint’ does capture a precise and observable influence. I would think of this though as much less to do with transmission of an aesthetic technique (for representing something) than with a change in the ways in which the idea of the difference between the material and immaterial became to be conceived in the twentieth century.

What we see in the comparison of these two pictures is similarity in the handling of paint marks by both artists. In both we also see the consequences of such handling on our perception as viewers of the boundaries between the figure or body in their painting and its ‘background’. Indeed Auerbach often begins to eliminate that difference. In Sickert this is emergent from a representational purpose I suppose and characterises his later rather more than his earlier work. Thus the delineation of the body of the model is absent when Sickert handles the paint that makes out that body of the female model in The Studio, especially at its margins. Marks of subdued colour that transgress any idea of boundary make something of that body that appears as if it were created by the hand of Sickert in the moment of his painting it. This idea is even readable from the fact that we see Sickert’s hand in the picture, holding the brush that ‘made her out’ of his oils. On the other hand, the model’s body is more delineated in the more precise reflection (on a two-dimensional surface) in the mirror behind her, Sickert is clearly playing games with representation whilst asserting the primacy of his ‘making out’ of a body that is entirely his material creation.

When Auerbach addressed this himself he emphasised the later Sickert’s increasing emphasis on contingencies and accidents in artistic process. Auerbach’s makes out of what he see the same contingency and accident that queers reality once freed of conventional perceptual filters. A ‘reality’ that is more accidental than ordered conventional norms and forms would have us believe. Sickert, he says:

… became less interested in composition, that is in selection, arrangement and presentation, devoted himself, more and more, to a direct transformation of whatever came accidentally to hand and engaged his interest, and accepted the haphazard variety of his unprocessed subject matter … He made obvious his frequent reliance on … [here Auerbach names various materials and contingent resources available to the painter] who played a large and increasing part in the production of his work. But these interesting ways of producing paintings would have been, of course, of no interest if the resulting images had not conjured up grand, living and quirky forms.[13]

At this point readers could seize on Auerbach’s last sentence to emphasise the representational objective but I think that would be a mistake. Just as with Bacon, Auerbach wants painting to make out forms that make up a ‘reality’ that is otherwise not commonly perceived – forms that are not just a matter of artistic pre-design, as in Clive Bell’s phrase ‘Significant form’, but truths masked by mundane reality. When made these quirky forms may appear to be spectral or otherwise queered to perception in other ways, as ‘conjured’ up magically. The material daubs, strokes, daubs and imprecise unlimited lines that ‘make out’ the artist’s artistic son, Jake Auerbach, from a background of paint.That thing s not delineated because what is ‘grand, living and quirky’ is also not ever simply delineated.

I’ve tried to argue thus far is not new and not unlike current thinking. The brilliant Timothy Hyman argues that ‘abstraction’ as a movement in art history merely side-steps the fact that the culture was undergoing a crisis in the very purpose and function of representation. Clement Greenberg and others simply ignored the fact that that where once artists could see, and therfore could imitate, a peopled space they called ‘reality’, there was now merely a Void. As Hyman says in the Introduction to his beautiful quirky book:

A sense of unreality in objects was shared by representational as well as abstract painters. The kinds of figuration … in this book emerged from the same existential experience, often referred to by the artists themselves as ‘The Void’; as when Picasso writes in 1932: ‘Each time I take up a picture I have the sensation of throwing myself into the void. Max Beckmann invokes ‘this infinite space, the foreground of which one must constantly pile up with any kind of junk so that one will not see behind it to the terrible depth’.[14]

Same ‘representational crisis’ there may have been for all of the new ‘revolutionary styles in the visual arts’, as Paul Tillich calls the shifts in twentieth century artistic styles in Europe.[15] However, the High Priests of the Dogma of the Primacy of the Art of the United States of the period of its neo-imperial expansion turn abstraction into a cultish and leading expression of the purity of a liberated Art. Of course these same high priests had to account for the existence of continuing Old World traditions and their overlap into the states, amongst which they would place Bacon.

An example of this I find in one of the old books on my shelves. It is the catalogue publication for a Museum of Modern Art Exhibition in 1959 curated by an expert in German Expressionism, Peter Selz. His version of Bacon is typical I think of art historians’ take on this artist from that period, wherein the paintings are read as if they were philosophical and /or theological statements of the existential isolation of ‘man’ (sic.) from a world that refuses to offer meaning to ‘his’ life. The exhibition catalogue it should be noted has a preface by the existentialist Christian, Paul Tillich, who interprets the sad fate of figurative painting in the twentieth century as a reflection of ‘a peculiar image of man’. The ‘new images of man’ celebrated in this catalogue and exhibition were seen as specific to post-religious modernity: found also in contemporary literary expressions of a new humanity in Samuel Beckett for instance.[16] Selz’s Bacon turns figurative imagery into philosophical meta-statement in this analysis of the then new Van Gogh paintings of 1956 and after by Bacon:

… van Gogh materializes in the fields together with a shadow from which he seems quite detached. Emerging out of the quickly receding space, he reminds us that time is on its way. … Always concerned with the vision of death and man’s consciousness of dying, Bacon has presented us here with the spectre of van Gogh returning from the dead to his familiar haunts on the road to Tarascon.[17]

An approach to Bacon’s painting that reduced it to what are, after all, just words, was heavily rejected by the artist himself. He may, of course, have protested too much in order to avoid the distaste for visual art that was designated ‘literary’ by Clement Greenberg and others. Didier Ottinger’s 2019-2020 exhibition in the Pompidou Centre in Paris showed more recently that painting can reflect literary work in much richer and more complex ways than by merely illustrating its statements. The latter can, of course. could be more easily ‘stated’ in language.[18] Ottinger cites Bacon’s highly pertinent remarks to David Sylvester in interview:

I think that in our previous discussions, when we’ve talked about the possibility of making appearance out of something that was not illustration, I’ve over-talked about it. Because in spite of theoretically longing for the image to be made up of irrational marks, inevitably illustration has to come into it to make certain parts of the head and face which, if one left them out, one would then only be making an abstract design.[19]

For my purposes, this states Bacon’s ambivalence about the problem of dealing with a representational tradition in the history of thought and feeling, which he elsewhere calls, ‘a whole kind of long process of human images which have been passed down’.[20] I see the quotation above as, in fact, Bacon’s version of Auerbach’s vision of the painter as the ‘sole coherent unit’ in the making of new images. That writers deal with inherited images in different media does not disqualify the originality of the ‘assemblage’ of those parts and in a new coherence. This would be so, as readers of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land know, even if the coherence was in the end only available to the artist who assembled it in any authoritative form.

I admit to an agenda in taking Bacon down this path, because I have long been concerned that the dry bones offered by the baneful history of art tradition will sap Bacon of his decidedly queer content. I sense this in the Stevens and Swan biography for instance in those authors’ search for authority in precisely that ‘baneful’ tradition. I strongly believe that Bacon, despite his own protestations, was aware that his relation to the figurative tradition was in part mediated by his lived queerness – a point that Bacon’s friend, Daniel Farson made in his neglected 1993 memoir of the artist. Such a life lived by Bacon in ill- secreted fishnet tights could sexually excite some policemen, and according to Farson did excite one policeman in particular. But that excitement was at the price of Bacon making himself more noticeable to police surveillance by laying on the make-up too. It is a life that robbed the living of it of the delusion of safety and comfort whilst making it even more potentially exciting on the nervous system: ‘He was the embodiment of all that was advantageous in being homosexual, and it has to be admitted that it frequently enhanced as well as shadowed our lives’.[21]

Bacon appeared not to value other contemporary queer painters in the figurative tradition as either artists or exempla of queer men. No work of art history ever really makes a connection between the choice of a figurative tradition despited its datedness to contemporaries and other queer artists. The latter would include John Minton and Denis Wirth-Miller, of course, and, more significantly from the point of view of the artistic outcomes in my opinion, Keith Vaughan. According to the latter’s biographer, Malcolm Yorke, Vaughan disliked Bacon in part for his reduction of relationships between men to something merely of the body and, in Vaughan’s view, thus relatively debased the range of expression open to queer men.[22] This is certainly reflected in Farson’s sour and world-weary reflections on Vaughan’s statement to his Journal (intended for publication) that Bacon’s ‘impressive dignity, his ardour and natural grace, his extraordinary physical beauty – supple – gentle – sensuous’, debased not only himself but any man who felt that immaterial stuff such as feelings of love idealised the physical body, making it suitable for metamorphosis into a model of a more ideal beauty.[23]

Such differences in view actually illustrate some of the tensions in the relationship of figurative art to queer traditions and are valuable I think in locating Bacon in a fuller psychosocial context that is honest to both queer and art history, something I, if not art historians, would be keen to be. And such a combination of duties to the fragmented experiences that add up to history is true to Auerbach’s thesis on art I think. An artist may be the ‘sole coherent unit’ in relation to an artwork because ‘what happens to’ people is never coherent, never understandable through one lens whether it be lent by the history of art or queer history.

In order to illustrate that I’d like to compare studies of nude figures in a setting or background by both Bacon and Vaughan: Vaughan’s Fourth Assembly of Figures (Transfiguration Group) 1957 and Bacon’s Portrait 1962, the latter thought to be a portrait of Bacon’s sometime lover, Peter Lacy (follow links to see the paintings). Clearly in neither case are figure and background as randomly separated as in our earlier Bacon example. In fact both painters utilise stylised lines to bound the body of their nude males in part. Nevertheless we are forced in both cases to see the arbitrariness of these lines in relation to the appearance of the figure(s). These lines sometimes adumbrate visible anatomical or physical features of the body and sometimes they appear to allow the painter to emphasise the freedom of the painter to make marks that break any illusion of representation, especially in the complexly jointed legs of Bacon’s figure where the independence of each limb cannot be established. And although one foot is drawn at the end of both legs (one unseeable), other organs are significantly ambiguous between what appears to be a matter of either internal and invisible or external and visible anatomy.

Significantly this ambiguity of what is inside and outside the body focuses on the figure’s sexual organs. Bacon’s figure is neither clearly drawn to mimic a figure that is ‘drawn’ in either two or an illusion of three dimensions. The curves that might have created such illusions often serve to flatten out an area of the figure’s body. The tension in this picture relates in part to gestures of sexual come-on. associated with relaxation and sexual defiance. Invited to sit with the figure, the setting takes away the viability of the invitation – deliberately undermining the function of the available seating-space for this ‘other’. The sofa’s arm dissolves in the space where the figure’s arm invites the viewer to turn to sit and the space morphs into a very unstable form indeed, like a slide rather than an ‘armrest’. Likewise the figure neither sits nor lies, as if slipping into discomfort were the body’s only available motion in such spaces. None of the spaces in this picture are all that stable of course. Whenever an illusion of volume is demanded it is just as easily undermined, as if the shapes were merely domains of flat colour rather than a stage side or a wall or a roof. The colouring of the figure helps to emphasise its near flesh tones but also reflects in some much darker green shades greens absorbed from its surroundings, as if ashamed of the tumescent status it also aggressively bruits with a snarl in teeth and nose. It is a disturbing picture of naked near rotting flesh. And in the end the colours seem to want to be more than the flow of paint that sometimes pools and coagulates – at the figure’s absent mid-legs for instance.

In contrast the three nudes in the Vaughan ‘Assembly’ are not only figures to the eye of the viewer of the painting, as always in the painter’s Assembly pictures, but also partial viewers of each other. The idea is a trope from mythic scenes of Christ’s transfiguration and elevation like Duccio’s, that we know Vaughan knew from visits to the National Gallery in London.

The figures in the Vaughan Assembly are partially delineated unlike Duccio’s. Sometimes a limb merges with its setting in effects that make the paint itself the obvious feature of connection between environment and limb. Likewise the colours of the scenic background, that make some small effort to represent sky and mountains (and even perhaps the faded gold of medieval models of this scene) are continually reflected within the bodies of the figures in patches or thick brush streaks that either fade out or are elongated in lines and shapes that ought not to elongated, or even present, if the aim had been representational here.

But how different these figures are from that one in Bacon’s portrait. They may be stylised in the manner of unclothed mannequins with characteristically absent genitalia, other than a patch of shaped ochre in the central figure. These men gaze on each other partly surreptitiously and may or may not be inviting each other to approach or return a gaze. They may pick out one another selectively (or not) but their aim is to await some kind of realisation in the eyes of one of these, or any other viewer rather than be easily interpretable and at danger of false recognition, as gay men were in the period (believe me!). The crisis of representation is still here. Men gaze at or glance aside at each other without knowing each other but there is potential in our gaze rather than discomfort and alienation, alongside attraction, in Bacon.

What I am arguing is that the relation of context and person, background and figure is a question asked of the viewer. The question is dare you approach me in order to see me or not. The fact that this approach is ambiguous in both paintings hides the fact that only one evokes the figure as either fearsome or attractive in itself. There is suspicion and fear in the Vaughan piece but it is not the suspicion and fear of the men of each other, or the viewer from the artist, but of a society of surveillance known to all queer people. It is suspicion about the possible meanings of the encounter they approach but never consummate. Danger lurks in the scenario itself – in one viewer getting the meaning of another wrong. The viewer of Vaughan senses the promise of seeing something change – the figure transfigured as it is when we might fall in love. This is not the case in Bacon, where the ambivalence of the figure is one that advises proximity and distance, liking and fear at the same time, and no transcendence.

Finally I would like to show that Auerbach’s view of the artistic process applied even to Lucian Freud, who clearly, and unlike any other example here, draws such that eye catches a delineated character. But is this the case? The meaning say of a wonderful self-portrait like Man’s Head (Self Portrait 1) 1963 plays figure and background against each other in a tense battle of colour contrasts and obvious manipulations of patches of oil paint.

A line between body and what is not body is not always easy to find here – the organic flesh is conveyed only by the organic feel of the brushwork but not ONLY within the painted body. It also signifies a background to the painting, which is likewise fleshly. As in other painted surfaces I have considered, here too the separation of attention to making out the body from the swirls of paint that indicate the visceral methods of their application throughout the painting is hard to find. The ‘sole coherent unit’ yet again here is not the figure or the painting as a whole but that unknown factor that paints, like the detached hand in Sickert’s The Studio, the remnant of his ‘self-portrait of an artist’.

I have puzzled over this piece a long time and, as with all I write, it says too much and yet not enough. But it points to places I think are worth reflecting upon. That the artist tries to make figures out of an area of paint is the sole coherent action in modernity where it does not aestheticize the art object as its sole interest. It is where figurative art tries to imagine the human in modern contexts where the meaning of what it is to be human may be forbidden, lost or hidden. This is even more so for queer artists who see analogies between the necessity to them of a fascination with appearances and the questions necessary to ask self and environment where the codes of relating have become less knowable – queered because they apply to conditions that are symbolically excluded from ‘normal’ environments.

So there it is.

Feedback welcome.

Steve.

[1] from Frank Auerbach (July 1961) ‘The Predicament’ in The London Magazine cited in Andrew Brighton (2018) ‘London: Painting in the Time of Modernist Art’ in Elena Crippa (2018)All Too Human: Bacon, Freud and a Century of Painting Life London, Tate Publishing. pp. 26 – 41.

[2] See Crippa (2018: 90) for reproduction. Copyright law, ever the enemy of any idea about art other than that of ‘ownership’ forbids reproduction so follow the link in the text to get an idea of this tremendous painting or put in your browser: http://francis-bacon.com/artworks/paintings/figure-mountain-landscape

[3] David Sylvester (1975: 63) Interviews with Francis Bacon London, Thames and Hudson.

[4] Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan (2021: 595) Francis Bacon: Revelations London, William Collins

[5] ibid: 232

[6] I sense the conventional academic art historians cringing here at the ‘unsupported’ subjectivity of my interpretations here but see it as a symptom of their constitutional hatred of the actual fuzzy edges of cognitive processes that are not the a-priori creation of that myth they call ‘reason’ and ‘argument’.

[7] Bacon’s 4 March 1972 interview with Andrew Forge on BBC Radio 3 cited by Catherine Lampert (2015: 143) Frank Auerbach: Speaking and Painting London, Thames & Hudson.

[8] Auerbach cited ibid: 142.

[9] Jodi Cranston (2010: 15) The Muddied Mirror: Materiality and Figuration in Titian’s Later Paintings Pennsylvania, The Pennsylvania State University Press.

[10] Brighton (op.cit.: 29)

[11] Crippa (op.cit.: 140).

[12] Martin Hammer (19!!) ‘The Camden Town Group in Context: ISBN 978-1-84976-385-1: After Camden Town: Sickert’s Legacy since 1930’ A Tate Research Publication Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/martin-hammer-after-camden-town-sickerts-legacy-since-1930-r1104349

[13] Auerbach’s Foreword to Late Sickert Paintings 1927 to 1942 (an Arts Council Exhibition in 1981) cited Lampert (2015: 125).

[14] Tim Hyman (2015: 10) The World New Made: Figurative Painting in the Twentieth Century London, Thames & Hudson.

[15] Paul Tillich (1959: 9) ‘A Prefatory Note by …’ in Peter Selz (1959) New Images of Man New York, Doubleday & Company, Inc., pp. 9f.

[16] ibid: 9.

[17] Selz (1959: 30f.)

[18] Didier Ottinger (2019) ‘Bacon Spelled Out’ in Ottinger, D. (Ed.) Francis Bacon: Books and Painting London, Thames & Hudson. pp.16 – 32.

[19] Bacon cited from Interview V of the Sylvester interviews in ibid: 19.

[20] Bacon in a Radio 3 talk on 16 March 1972 cited ibid: 19

[21] Daniel Farson (1993: 23f.)The Gilded Gutter Life of Francis Bacon London, Sydney etc., Century (Random House imprint).

[22] Malcolm Yorke (!990: 162) Keith Vaughan: His Life and Work London, Constable

[23] Farson, op. cit.: 115f.Cited, without acknowledgement to Farson at all, in Steven and Swan, op.cit: 362f.

4 thoughts on “‘ … painting as something that happens to a man working in a room, alone with his actions, his ideas, and perhaps his model. … he seems to me to be the sole coherent unit’.[1] Figure and Body made out of a whole background of Paint.”