‘We are so many, …. Every single one of those people … bound to different destinations at which each will find themselves, as ever, the protagonist of the story. Every single one the centre of the world, around whom others revolve and events assemble. … So much necessarily lost, skated over, ignored, when the mind does its usual trick of aggregating our faces’.[1] Reflections on Francis Spufford (2021) Light Perpetual London, Faber & Faber.

The quotation in my title is, in some ways, typical of the way this book works. The language has the feel of something that is considered weighty as a reflection on life. It’s a weightiness that we expect from the pulpit or from the philosophical communities in Iris Murdoch’s novels. In fact it is meant to transcribe the thoughts of one of the more amiable characters of this novel: Alec, as he heads home on a crowded London tube train. Alec is one of the men who dies as a child in the first chapter of the novel and then lives again through the process and historical stages of this novel, exemplifying in doing so the changes wrought by accidents. These are accidents that make a difference of life and death but also include changing national economic and social circumstancess.

The word ‘accident’ is not used by me, as it were, ‘accidentally’. There is a sense in which the ways individuals relate to major historical and life-changing events is often seen as an ‘accident’. That relationship is a matter in which widening spheres of context – from the very personal to the world-changing – vary how any individual character in this novel experiences history. To experience history is to see the time and place one inhabits become interpreted as the process of history in action. For history is both an agent and a passive interpreter of individual lives. It throws us into new relations to time and space, opening up not just opportunity but means of interpreting that world of opportunity. All individual opprtunities are ambivalent of course. For what is this an opportunity: personal development and growth, exploitation of others, building communities and communal action. For instance, the character Jo expresses this idea in a moment of a revelation as ‘a message’ comes though, ‘loud and clear from her psyche: this is an accident. There is no need for her life to have worked out like this at all. So many other possibilities’.[2]

Likewise Alec’s significance, both in his own self-assessment and in the view of readers, is only known to a view of history that looks back to major turning points that may have seemed less obviously to be turning points to the people to, and at the time which, in which they occurred. I personally rejoiced to see a novel being written again that saw it as is role to explain how text and the cognitive paradigm breakers they contain come into our lives and change them together with other forces. The effect can be direct, as for example, when Alec chooses to teach his new learning as an agent of change, even in informal situations such as by replicating the teaching function Tressell’s The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists in talking to his son Gary’s YTS intern.[3] Alec has already lost his role in printing Rupert Murdoch’s Times newspaper – once a major labour-hungry industry that became in the process of history, historically redundant as a form of manufacture and earning a livelihood. This leads him to choose an Open University course, wherein he confronts the work of Antonio Gramsci, John Berger, and Paolo Freire and other monuments of the twentieth century expanded politico-literary legacy of the Marxism of a new intelligentsia. Such changes in his thinking alienate him from his working-class wife, Sandra, to whom educational opportunities had never been available. And this is only one of the ways in which change, including the contingencies of what education is available to whom, becomes to be felt in our interpersonal relations. As he thinks of the possibility of her being ‘unfaithful’ to him, he says to himself:

What if she’s just … lonely. I’ve been in this room, changing. And the more I’ve changed, the less we can talk about what’s on my mind. We can’t have conversations about Paolo Freire; I mean we’ve tried but it doesn’t work.[4]

Change brings both to him and a new generation of formerly employed mature students a revival of sexual opportunity, that feels to those people strangely timed in what they had thought were settled lives. There is a convincingly rendered picture of resurrected freer sexuality, for instance, at Open University summer schools which Alec, and others, experiences as a developmentally ‘anachronistic idea’ (derived from living in ‘an, eighteen-year-old’s room, with an eighteen-year-old’s tiny bed’). This historically situated phenomenon amounts to a major reconfiguration of the norms scheduled into ordinary lives.[5] Time and change, both as the inevitable result of mortal things, and the contingencies of active shaping made possible in and through cultures, shape the trajectory of each individual’s life-story, and of those on whom life-choice, events and contingencies have bearing. This is the very stuff of this novel; indeed, perhaps of art generally.

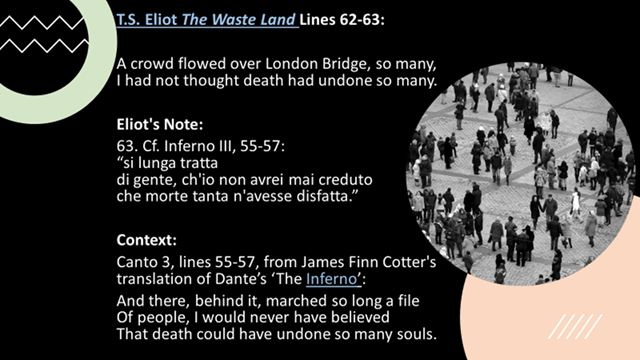

And this is where I’d return to that thought of Alec’s given in third-person perspectival prose in my title. I called it weighty; indeed over-weighty. It is not, when I think about it, that Alec could not, following his Open University course, have thought in these terms, but that he does so in the way as other characters in the novel do, such that they become exempla of a literature of worldly mutability, with a tradition as long as that of literature itself in all languages and cultures. Alec becomes enfolded in the authority of literary textual tradition. When Alec thinks of the humanity on the crowded tube train on which he travels home around him, his words, I think deliberately echo many other literary contexts, from the young suicidal and sibling murdering son (called affectionately before this event by his parents, ‘Father Time’) of Hardy’s Jude the Obscure of 1895 – Done because we are too menny (sic.) – to T.S. Eliot in 1922, himself citing Dante from medieval Italy: ‘We are so many, Alec thinks’ (Spufford’s italics).

I suppose my point here is that Spufford’s novel is very consciously in a literary-philosophical tradition of meditation about the origins and destination of change, with the normative repertoire of counterthemes like the threat of death. Amongst such novels I’d include Ali Smith’s The Accidental as a major textual innovation of that old song in world literature. This comparison is not to, in any way however, castigate Spufford’s novel but it is to suggest that Perpetual Light is not a novel that attempts to innovate in its writing, as say, Ali Smith, magician of these themes, always does. One can’t escape, of course, in Spufford as one gloriously does in Ali Smith, the Christian take on death as a transmutation of all flesh, which as we know from long tradition, is grass in that light, or else it is ‘dust to dust’.[6]

There is sometimes a kind of clunkiness in Spufford’s treatment of a retrospective view of changes that were not seen to be as significant as they were, at least by everybody, at the time they happened. We can look at the novel’s treatment of the Rupert Murdoch ‘revolution’ in the press for instance, in the name of an information limiting and owning multinational capitalism. These historical forces are reconfigured in the mind of Alec, then as a seasoned trades-unionist speaking to a representative of Murdoch journalism from a distance, that Spufford calls Hugo Cornford, thus:

“We can deal with the Tories,” says Alec. “We saw them off last time”.

“This is going to be different. They are not the half-hearted politicians you’re used to; … I’m afraid you chaps are going to get blown away like dandelion fluff. …”.[7]

That ‘blown away’ is significant, for a novel that begins with all its main characters killed by a German bomb in 1944 when they are all primary-school children. The rest of the novel takes these dead children through the story of their lives as if they had not disappeared in 1944 but confronts them with many versions of death in which they will be ‘undone’ (again in Dante or Eliot’s terms) or ‘blown away’ by forces and dynamism quite unlike that of a bomb.

The portrayal of historical forces ranges wide, including the digital revolution, the subsequent rise of disinformation on the internet and the links between it, say, and the explosion of cases in childhood bulimia and depression which surfaces in the character of Alec’s grand-daughter. Sometimes however the resurrected character set of the novel, the people in the stories they assemble round themselves in those new lives, and perhaps the stories themselves, survive being ‘blown away’ by events in history. Sometimes, however, as in the case of Claude, Jo’s husband, they do not or only marginally so. Jo see Claude, ‘framed in his chair like a badly lit still life’, about to succumb reluctantly to the soporifics that pass for anti-psychotic medication in the mental hospital to which he is confined by accidents too numerous to mention, including those, possibly, of genetics.[8] His life is almost irrecoverable except but for Jo’s witness to it. In that sense he is like the Woolworths store that has disappeared in history from the bus-stop where she is used to get off the bus after visiting Claude. This is a vacant lot, like those in T.S. Eliot’s poetry, ‘where the old Woolworths used to be’ and where ‘she keeps rediscovering that it isn’t there’.[9] That is why Claude’s experience of mental ill-health has to be balanced by that of Ben, whose life is redeemed, or so the novel tries to engineer out of the rhetoric of light, near the novel’s finale, of falling dust.

If mental illness or the failures of retail capitalist development don’t get the characters, perhaps other innovations in the history of human invention or making-up of things will, such as the computers which play such a part in the ending of Alec’s first working life-span as a Times newspaper compositor. Not that change is not ambivalent. Computers are as Alec tells his granddaughter, ‘“made of light”’.[10] And there we have it – that clinching metaphor (‘perpetual light’ indeed) echoing through the novel from its first instance in the brilliant line from Henry Vaughan, Spufford uses as an epigraph: ‘They are all gone into a world of light’. Seventeenth-century metaphysical / religious verse is meant to take a counterweight to a world of sad capitalist expansion based on the greed at the root of the neo-liberalism Spufford, rightly in my view, associates with Margaret Thatcher. But for the non-religious, like myself, this alternative is too light in another sense to weigh enough to balance worldly greed.

Capitalist greed is associated in this novel with the character of Vern, who, like the victims of his practice as a London landlord and developer, also falls, with his family, prey to the apparently impersonal forces of the market or ‘the bloody interest rates that did us in’.[11] His vision of a future of London’s East End of skyscrapers is based on the dismissal of historic lives:

“… – these people – this place – it’s all very nice, but it’s basically over. It’s the past, innit. And I’m not bothered about the past. I’m for the future. Look around’jer. Who’s the future, down here, eh? … It’s us. Who’s the future? We are.[12]

Although engaged in ‘Nothing dodgy‘ such as ‘Rack-man stuff’, Vern only becomes ‘a property developer’ once he can openly put his financial interests before honest and integrity by playing on the susceptibilities of financial backers who can be persuaded by flattery to sign agreements they have not read. [13] Of course Vern’s properties themselves age as the venture capital projects associate with him also age and get played out: ‘the brick and the stucco and the pebble-dash, the concrete and the glass (tired now) that meant new times when Vern was new’.[14] But Vernon is no longer new as the novel progresses through not only his aging but the end of the ability to capital to produce profits where it produces no qualities worth having or sustaining.

By the 1994 of the novel’s sequence, Vern’s love of Opera is ‘clever beauty’ that nevertheless causes him, ‘a thread of unhappiness tightening inside him, a faint signal, growing stronger, that something is wrong’. He does not know why, but Spufford’s descriptions of the music of opera make it clear that musical harmony is a matter of something that only works in and by virtue of time and variation, change and constant mobility of mood.

Actually buoyant, possibly sad! say the violins. Possibly buoyant, actually sad! reply the cellos. Whatever you feel, the woodwinds put in, it will be quite clear. Though subject to change! the violins reason. Though subject to change, the woodwinds concur.[15]

An operatic hymn to time and change is after all what this novel provides as a whole – a consistent rumble of variations and dialogue in the score with some fine arias by a cast of quite different characters, each really creating a version of that story of mutability through the process and accidents of time.

But of course, despite the shadow and the discords, there is always the notion of a ‘light’ that lasts forever and is itself unchanging – perpetual light. Spufford gives that a serious try to realise moments of achieved beatitude for his characters. Note Ben waking up with his beloved Marsha. He gives this moment a kind of being outside time by inventing in the behaviour he observes in his loved person a kind of sacrament.

… little impulses moving in hr round face that come to nothing, but buffer back into stillness before they can expand into real expressions: the outward and visible sign that, within, the kaleidoscope of dream is shifting and sliding the panes of memory against each other, in combinations too strange and fleeting to call out definite reactions. There is far more of her than there’s ever time to reckon with in the businesslike daylight. Marsha Adebisi Simpson is in the depths of Marsha Adebisi Simpson. But she is surfacing, getting closer to the light, drawn up, lured up, by Ben’s fingers.[16]

Mixed with the mysticism that plays out in the gap between exterior and exterior being, surface and depth, the finite and infinite, ordinary daylight and lasting spiritual light is something spiritual and enduring, or at least so the rhetoric tries to win out of us as its readers. Surely the point of mirroring the Anglican and Lutheran definition of a sacrament which I italicise in the quotation is to embody here the possibility of a transcendent reality housed in the indefinite.[17] In such realities there is ‘far more’ to see than there’s ever ‘time to reckon with’: something beyond the mundane of daily business.

In the same chapter, Ben’s acceptance into the church attended by Marsha is remembered together with Pastor Davies’ sermon on the nature of Christian salvation in which London, ‘this dirty town’, becomes transformed into a version of the New Jerusalem dressed in light, ‘new and holy’ outside time. Ben reaches a beatitude which has otherwise no place in the structures composed from mundane experience of time of the novel’s narratives about change in the lives of individuals. It is not only outside time, but also a ‘world of light’ that Henry Vaughan spoke of in the novel’s epigram and it ‘dazes’ Ben with its passionate light.

And Ben thinks, dazed as he always is as the pastor reaches his climax and the choir ascends to ecstasy: I am safe. I am, though I don’t know how or why. Thank you. [18]

This is the best example of what I see as Spufford’s attempt to fashion belief out of the doubtful and uncertain stuff of time. Of course, readers like me depart Spufford’s authorisation of such moments precisely then and refuse to see more than the rhetoric which points to that safe place beyond the world and mundane human knowledge. Religion as a set of propositions will always have that effect on the determinedly non-religious. It is, as Pascal would say, the risk we take in the wager that God and eternal salvation are myths.

So, though for this reader Spufford’s harmonic and infinitely well-lit notes ring false, I admire the novel’s prose. Literature though, I think, can only confirm belief that requires to be sustained outside its pages not create and maintain such beliefs. What do you think?

Steve

[1] Spufford (2021: 280f.)

[2] ibid: 301

[3] ibid: 246. YTS or Youth Training Schemes such as are referred to here in relation to the circumstances of 1994 are, of course now themselves consigned to a sad history of the failure of British society to care much about the children of the working class.

[4] ibid: 261

[5] ibid:255. This reminds those of us who have studied and taught with the Open University over many years that even those summer schools are now long assigned to dust by the economies of modern education and the shift to cheaper digital versions of at-distance teaching encounters.

[6] Read ibid: 319 & 323.

[7] ibid: 131

[8] ibid: 300

[9] ibid: 303

[10] ibid: 262

[11] ibid: 149

[12] Ibid: 58 (my omission, Spufford’s italics)

[13] ibid: 57ff. The term Rack-man is spelled thus (ibid: 66) but refers to Peter Rachman. For further information on Rachman see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Rachman for information on this contemporary model for Vern’s ‘enterprises’.

[14] ibid: 267

[15] ibid: 230f.

[16] ibid: 188. My italics emphasise the ‘mirroring the Anglican and Lutheran definition of a sacrament’ that I mention after this paragraph.

[17] “When sacramentum was adopted as an ordinance by the early Christian Church in the 3rd century, the Latin word sacer (“holy”) was brought into conjunction with the Greek word mystērion (“secret rite”). Sacramentum was thus given a sacred mysterious significance that indicated a spiritual potency. The power was transmitted through material instruments and vehicles viewed as channels of divine grace and as benefits in ritual observances instituted by Christ. St. Augustine defined sacrament as “the visible form of an invisible grace” or “a sign of a sacred thing.” Similarly, St. Thomas Aquinas wrote that anything that is called sacred may be called sacramentum. It is made efficacious by virtue of its divine institution by Christ in order to establish a bond of union between God and man. In the Lutheran and Anglican catechisms it is defined as “an outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace.” See https://www.britannica.com/topic/sacrament

[18] ibid: 200

2 thoughts on “‘We are so many, …. Every single one the centre of the world, around whom others revolve and events assemble. … So much necessarily lost, skated over, ignored, when the mind does its usual trick of aggregating our faces’.[1] Reflections on Francis Spufford (2021) Light Perpetual London, Faber & Faber.”