Liberating resistance to the maintenance of the ‘very fragile fucking structure’ of accumulated culture and its oppressions.[1] A preliminary set of comments based on a first reading of Jenni Fagan’s (2021) Luckenbooth Richmond, London, William Heinemann/Penguin Random House. CONTAINS SPOILERS

Dot turns as a splitting sound ricochets over the sky – the skeletal wooden beams of Luckenbooth are fractured.[2]

Luckenbooth ends with the cataclysmic collapse of a man-made structure described in terms of the many organic-anatomical, conceptual and built structures that are a key motif of the rest of its pages – whether human, animal, physical, cognitive or a fantastic-symbolic construct such as the bone mermaid made by Ivor. The death watch is both partially performed, or at least aided, by Dot, a radical investigative writer, who picks at its decaying and death-watch beetle eaten limbs down to its very bones. It is she who puts a full stop to that diseased structure but she is also one of its many victims destined to be buried with it. The end she marks is merely singular (perhaps with the significance only of one powerful sentence – such is the role of a Dot) and not an answer to the questions the novel raises about the oppressions in which history still buries us all: ‘she is just a Dot who took one building down’, – a significant building but yet only one of many that still stand over us and oppress us, even making us love them.[3]

In an interview by Denise Mina organised by the Edinburgh International Book Festival, Fagan made it clear that she searched the area around the spine of an old city that is High Street and the Royal Mile to find a space in which a tenement the size of no. 10 Luckenbooth Close might have existed. Having found it, she rooted it there, including it as a base for imagined views of the city or perambulations through it which start there. These views and walks are recognisable in the prose to anyone who loves Edinburgh behind the merely touristic facades. But this is also a building that operates allegorically, like the Panopticon structure in her first novel. But we should not assume that Fagan invents the symbolic picture of the class system since they are already marked in the structure of the old tenements. I found, for instance, this old print that illustrates the move from luxury to poverty in progression up what was a real collapsed tenement from the history of Edinburgh High Street.

However Luckenbooth joins other novels that use the structure of a communal building to organise and justify their plot structure, and perhaps point to other inverse hierarchical structures like that of a city or society as a whole. One example is Zola’s Pot-Bouille, translated into English not by the literal title ‘stew pot’ but as This Restless House, although Zola uses the structure of the house to allegorise a new development in the relations between classes in Paris and Second Empire France. That both new developments were, like the aged No. 10 Luckenbooth were, despite the appearance of newness and solidity, also ‘very fragile fucking’ structures.[4]

Dot is an unpublished novelist unable to survive in the culture of her period and in this sense too cannot undermine the examples of structural oppression in official Edinburgh culture – the Culture of which the evil and diseased Udnam is the Minister, ‘a man of letters’, in the opening of the novel – though she does that, with one symbol of it that is No. 10 Luckenbooth.[5] Dot’s analysis of culture is precise and correct but she cannot change more than its symbol. The house is a witness to Edinburgh culture according to its structured-class perspective. The privileged (‘the many snobs of Edinburgh’) who live nearer the bottom of the building view oppression with the eyes of those who pay no or little attention to the inequalities and environmental damage caused by their unseen obsession with status.[6] In the middle and higher stages of the house, height gives yet more access to the hurt and labour and failure that they alone see and must take into account. This is the duality not of Luckenbooth but of Edinburgh entirely, a duality marked in Scottish literature from Hogg’s Confessions of A Justified Sinner and later Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde: ‘It’s a city of duality. Lack of investment in communities perpetuates it. … It is a most uncompromising city’. But Dot alone will not end this lack of common interest that Edinburgh represents because ‘Dot is entirely alone in it and nobody wants her’.[7]

Dot’s radicalism dies with No. 10 Luckenbooth because she lacks the ability to span dualities – of compromising with the oppressions she exposes and finding a political voice. The same I would say is true of Anais in The Panopticon. And it is here that Fagan’s art is at its most subtle and nuanced, since her role is to do just that: survive, ride the dualities and contradictions and construct art that challenges as it satisfies. There is no doubt in my mind that Fagan is emotionally with Dot in her summary of the world in which the cultural worker – be it poet, novelist or visual artist – works, with its structures torn between privileged acceptance of the status quo and radical impetus to change the same. But a consummate novelist lives in that contradiction, never supersedes it. After all, she knows it is too powerful and its maw is stuffed with non-compromisers like Anais, Dot and other Queens of Bohemia. Dot says of her Edinburgh art school:

The arts! middle-class kids are raised to own a space. Keep others from infringing on it. And they are very successful at it. Edinburgh – makes a show of herself on that point – at every possible opportunity. Siphons money from punters. Keeps her truth-tellers under the vaults. As if they are diseased. There are gatekeepers who keep the arts hostage. They bang their drums and say: this is our space – we own all of it! They say – culture belongs to people like me. I let people like me through and they have to thank me for it. They say don’t you dare make us uncomfortable or we will close ranks like flying monkeys.

Dot is not about owning anything at all.[8]

Yet to see only the narcissism of high culture in the compositional structure of the Book, and other Arts, Festivals is to miss the nuance that such structures also incorporate. Simultaneously high art can stoke the illusion of total artistic control and simultaneously undermine its defensive structures. Dot is unable to take this latter attitude but Jenni Fagan can, attempting to carry her liberatory and anti-oppressive meanings right into the gaps in those ‘very fucking fragile’ structures and challenging them, like the Mother of all death-watch beetles from within. For fragile these structures are in fact are, although it may take a crisis like a pandemic or other harbingers of Apocalypse. A successful novelist must own her own structures as Dot cannot – possess them in the interests of challenging a society based only on principles of appropriation and exploitation or other characteristics of past literatures, even though the sum of past literatures is a ‘psychic vampire’ since, ‘it drinks human essence’.[9]

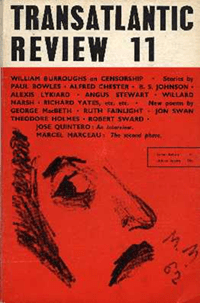

In the metaphor of the ‘psychic vampire’ I am recalling the person reported as that phrase’s author, William Burroughs, who himself appears – reinvented in Fagan’s novel on the basis of his attendance of the 1962 Edinburgh International Writers’ Conference. Burrough’s actual attendance is well recorded and his statements exist as they were translated into a Transatlantic Review article in 1962 (Issue 11).

Burrough’s contribution to the Conference certainly stresses his belief that what people think when they read is controlled by governments through their willingness to censor creative writing and assumption of that ‘right’. He asserts that censorship controls ‘what thought material of word and image will be presented to their minds’, but in this writing does not give details of how that process works.[10] Much of his commentary is an explanation of the use of cut-up and fold-in compositional methodologies in his own writing. He points out, in doing so, that, as in all writing, he uses the methods of the censor: ‘i edit delete and rearrange as in any other method of composition’ (sic.). My own guess is that the Burroughs character re-invented to inhabit part of ‘No. 10 Luckenbooth’ by Jenni Fagan elaborates Burrough’s views in line with her own analysis. She ties these together with a source of such thinking in the example of Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, of how thought control in writing works, and of the dangers of ignoring the conventions that sustain the status quo. That is, ignoring these conventions is dangerous if the writer is to survive their criticism of a society or culture that is unwillingly to be thus criticised and to lose its right to ‘manipulate us into believing that they are the power-house’. Dot, of course does not survive. Neither do other truth-tellers who get buried inside the walls of oppressive social structures. This concern with social and institutionalised structures never appears in mainstream English newspaper reviews I noticed though it is central in Malcolm Jack’s review of the novel for The Scotsman.

Whether she’s writing a PhD thesis using Kafka as a prism for examining the individual’s place within societal institutions, or doing up and selling derelict houses to help fund her writing career and support her young son, structures and structuralism obsess Jenni Fagan.[11]

It is this analysis in particular which lines up the literal ‘structure’ of a tenement, with other social structures that oppress us whilst they ‘raise’ us, to which I would include that conventionally expected of novels. Here is my first example:

Society says that we must communicate in mainstream ways only. We must conform to what is expected or we shall be ostracised, or worse. Having our own thoughts to respond to the institutions that raise us almost impossible. … What would we do without the distraction of words ordered into a structure that keeps us behaving in the way the structures want us to?[12]

This is a thorough amplification of ideas that lead to Dot’s undermining of the structure of No. 10, Luckenbooth Close, as is a second example. But I use this second example to show how Fagan both underwrites the critical theory of the role of culture (the evil Mr. Udnam is Minister for Culture) in animating her novel but also undermines it – in order to keep even readers suspicious of political motive on board. Fagan’s Burroughs, starting with a common interest of both authors in Wilhelm Reich’s psychoanalytic theories, talks about the transmission of language as a tool to make us:

… fear and loathe what it is they desire – … It labels all things – other – as something to be destroyed. The flesh knows its own queer predilection or its lack of normalcy and it denies it … so called reality lies to itself and to everyone else. … We are all at the mercy of and malleable to the programmes that raised us – whether they be religious, or class-based, or gender-biased. All structures are implemented through an underlying violence and brutality particular to the planet.

Do you think I’ll understand this when I’ve straightened up? John asks.

Aye.

You tried Scottish![13]

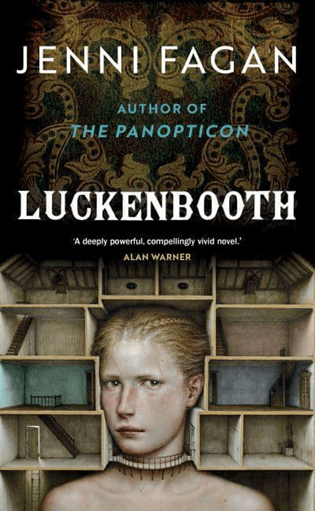

Class, gender and religious structures and institutions certainly do initiate and sustain a variety of oppression in this novel, and all are apparent in moulding the history of the Luckenbooth Close tenement and its inhabitants. Those who fail by such standards are buried in its walls, as the fine cover illustration of the first edition shows quite graphically: with a structural balustrade acting as a ‘choker’ for the androgynous figure pictured therein. But the passage, whilst including this political analysis also simultaneously undermines the intellectualised discourse in which it is cast. This is not the least because it too sets up a hierarchy between the formally educated and those who are not. Of course, it must also comfort readers struggling or ‘uncomfortable’ with it. And, as Dot tells us later, quoted in this blog at an earlier point, one element of the contract between bourgeois society and the radical writer, one she cannot fulfil but for which Fagan makes hidden compromises (for the purpose of ensuring her voice survives) thus to do, is not to ‘dare make us uncomfortable’.[14]

In this passage Burroughs’ young male lover adores but fails to understand Burroughs’ over-educated discourse. At such points readers rest on the beautiful conventions of plot, character and character interaction fundamental to the novel’s traditional structures. Politics hangs latent and perhaps can be discarded – it helps keep all readers ‘comfortable’. Even speaking for myself, I notice I thrill aesthetically more at Burroughs constant self-interruptions in that discourse to say how much he loves John’s beautiful young body, and especially his ‘cock’, illuminating relationships of queer love (with a mix of sex/gender variations and orientations) that also mosaics the novel than with the elements that ape a literary thesis.[15] My favourite such interruption is this:

You know, John, when I was receiving ever more criticism and they wanted to ban more of my work, …We went up to the top of a volcano. We took something … It’s called DMT – the spirit molecule – I won’t go into it right now because your beauty is distracting me, …[16]

Burroughs life and its intimate connection to the experience of censorship – in both subtle and non-subtle applications – calls out of him the need to liberate, here chemically, a means of liberatory vision. But it is a wonderful novelistic strategy that disrupts that visionary discourse, turning the reader’s attention to a close personal relationship that takes precedence in the moment of narration and engages the reader with characters in a plot element in a most wonderfully human novel. That these human moments are moments of queer personal interaction is important, however. If Fagan is to make a reader ‘comfortable’ again and exonerate them from the charge of being a potential force towards censorship of the writer, she does it on her own terms, ensuring that no relationship in this novel is ever not queered, even when it might appear normative.

It is at this moment where I think I need to invoke Fagan’s feminism which remains a beacon and model in a time when a movement that calls itself ‘radical feminism’ has taken up the cudgels against any questioning of the foundational truth of ‘biological sex binaries’, particularly in Scotland and particular in the form of the writing of J.K. Rowling. In this latter camp, Jenni Fagan’s feminism does not and cannot sit, for it refuses simple biological determinisms as does any scholarly understanding of biology itself. As a writer, no-one has done more to champion the radical importance of understanding what the study of biology really tells us, as in the amazing story Pluripotent, which focuses on the biology of pluripotency in cell development, she contributed to Smashing It, a collection of stories about class in modern writing and visual or performance art. Whilst Rowling generates fear of transexuals, even when writing novels under the male nom de plume of Robert Galbraith, the central intersex character in Luckenbooth, Fiona, is a moral lynchpin to a world of transgression between nature and culture, where transgression operates on both sides of that balance of variable qualities.

There is no desire here in the writing of Flora for the writer to distance herself from the phenomena of sex/gender whether rooted in theatrical showmanship or the slippage of biological traits in forms of intersexuality. The private camp ball held by Greig, her former lover, in his flat, in no. 10 Luckenbooth, is a miracle of writing in which moral, physical and cultural transgressions are ‘safely contained’ in the mere fact of their existence in a short piece of time outside the norms of a society that, in secret, perpetuates much worse.[17] That outside world of cathedrals and strict non-transgressive dressing includes Udnam who disrupts that party, where Hugh MacDiarmid in person and talk of Nan Shepherd’s poetry cross with sex/gender play behind curtains in the bathroom, like a rotating ‘disco ball … in the glitter’. We shift between fluidly gendered identities on the very cusp of danger but never falling into it. That cusp is illustrated in, for instance, the strangling swoon created in Flora by Greig, ‘with just the exact right pressure’.[18]

This isn’t because the writer is morally absent but, I would argue, because she shows phenomena for what they are rather than as they are distorted by a value system that others them, in the J.K. Rowling mode. People are not just in their bodies but those bodies are shaped by the institutions that discourse upon them in culture. Fagan’s beautiful adoption of an alliance between the function of culture, in naming phenomena, and living inside the actual variants of the body is shown in Flora’s memories of Greig’s first seduction of her, wherein, because of the imaginative fluidity of his words, Flora can be, because she can name, a whole not a body split by someone else’s binaries and oppressive dualities that even re-invents time:

Her man from the beginning of time had taken her to bed. He made her feel more free than she thought it was possible to feel. He told her she was a chimera. It was the first time she had heard the word. There were other words before that. Freak, hermaphrodite, boy-girl, in-between. He was the first one to tell her that she was not two things but one perfect creature made from stardust.[19]

A lot of meaning hangs on that word ‘chimera’ because it belongs to two contexts both of which matter in performing, as it does, the function of metamorphosis. One relates to the mythical imaginary, the other genetic biology. If Fiona is a chimera she is not made from the symbolic imaginary alone but from the interaction between that and biological processes that is in fact the truth of sex/gender variation.

We are prompted, of course, to query the word’s potentiality, precisely because of Fiona’s prior ignorance of it and because it sustains almost magical status as a means of revising the progress of time itself, making for new beginnings, that are subtly embedded in the writing up of her experience, including subtle metaphors such as ‘her man from the beginning of time’. Yet such latent meanings illustrate not only the liberatory in Fagan’s thinking but the care with which she communicates it which is quite unlike the openness of her more radical, but thus more endangered, avatars in the novel. It plays literary games. It is the stuff of a special kind of nuanced literary achievement. It is what marks her as a writer and an artist, who will survive her own radicalism and the censoring power that it held, even with a writer with the acknowledged status in world literature of William Burroughs.

This play with the magic or the fiction of time is, of course, fundamental to how this novel structures itself not only in the spaces that add up to !0 Luckenbooth Close but to the shifts in time, which certain characters transcend, even when that time ought to have swept them away into the past, such as Jessie MacRae. Manipulation of time is a trope for writing itself used by Fagan’s Burroughs (and Burroughs himself of course) when that writing survives its transmission to a readership. Such writers are able to say that they are:

… a time-bending machine – time travel is at my fingertips. … People who I have not met, who I will never meet – those people are reading my words right now. in their own personal way they make those words come to life, but they have travelled from me right to them right here.[20]

There is so much that could be said of this novel and this reading of my own is meant only to capture my first reading. As one returns to different episodes and to passages of superb writing, new meanings emerge. About Levi, for instance, so much and so many of the books deep political content hangs. However, it seems wrong to leave without saying a little about the invention of Mr. Udnam, who represents the agency of structures of class, religion and gender in culture – who keeps his fiancée, Elise, ‘in check with the fear of murder’.[21] Ready to delete everything that is not apparently normal or too openly queer, he indulges in a kind of private subversion of those structures himself. His sexual congress with Jessie, for instance, is built upon him viewing the sexual interplay with Jessie of his fiancée, whilst he enchants everyone by the size of his phallus: ‘His thing is huge. I don’t want to stare at it but it is hard to ignore’.[22]

But that much of Udnam’s grandeur is illusion is also most certainly the case. Such men hog the light of public appearance whilst alive and continue to do so, as statues, when they are dead. It is, I would venture to say, Fagan’s Burroughs who categorises Udnam so well. Far from being comfortable in their own masculinity, they are diseased – in the sense of lacking ease in themselves as well as being literally unable to be themselves with total control of others and the environment. Burroughs says he is:

… free – so many men are diseased and by that I mean they are dis-eased in their own masculinity. In their desires both homosexual and heterosexual, they are so twisted by it the only answer they have is to try and control literally everyone – women, children, dogs, trees, oxygen, space, other men.[23]

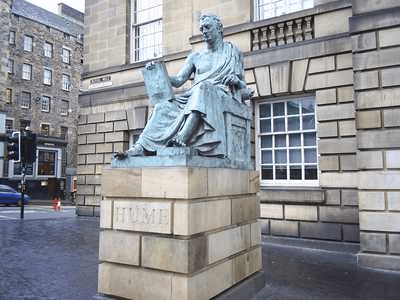

This sense of being bound (literally made unfree) by the cords of one’s own twisted masculinity is the feminism the novel in small, a feminist analysis as vital to the men in the novel as the women though not in the former’s agency. Control usually means censorship and eradication of anything that is perceived as other to masculinity – even other men. It means dominating the visible built environment with their image. Take, for instance Edinburgh High Street, or even the International Book Festival’s very own Charlotte Square. Men dominate. Charlotte Square by the monument to Prince Albert, High Street by David Hume. Whilst Hume commands High Street, before it turns into the Royal Mile on its ascent to the Castle, he does so by asserting even in his iconic classical robes, his right to last to eternity. Meanwhile women are ‘buried into the building by men who couldn’t tame them’.[24]

There is a whole important strand of the novel that celebrates wild nature before it is tamed and equates oppression with the built environment and the institutions – of class, gender and religion – that it represents. in walls especially women are immured and their fertility mocked because it cannot be controlled by men. Personally, I feel that there is a work of thought to be done to begin to articulate these themes from, where I think they lie, in its metaphors of bones and in how biology and culture interact in ways that are not as simple as binaries like those of the ‘wild’ and the ‘tame’. This would involve trying to understand the role of Levi in the novel. I am not there yet. As Levi says:

We can change everything in our mind: synapses, programs, ideas, thoughts, false histories, unobtainable futures – it is dangerous and it is not good for me but I won’t stop doing it, not for mermaids, or sirens, not for dictators, or racists, or creeps, … I won’t stop thinking as deeply as I possibly can, for nobody.[25]

Steve

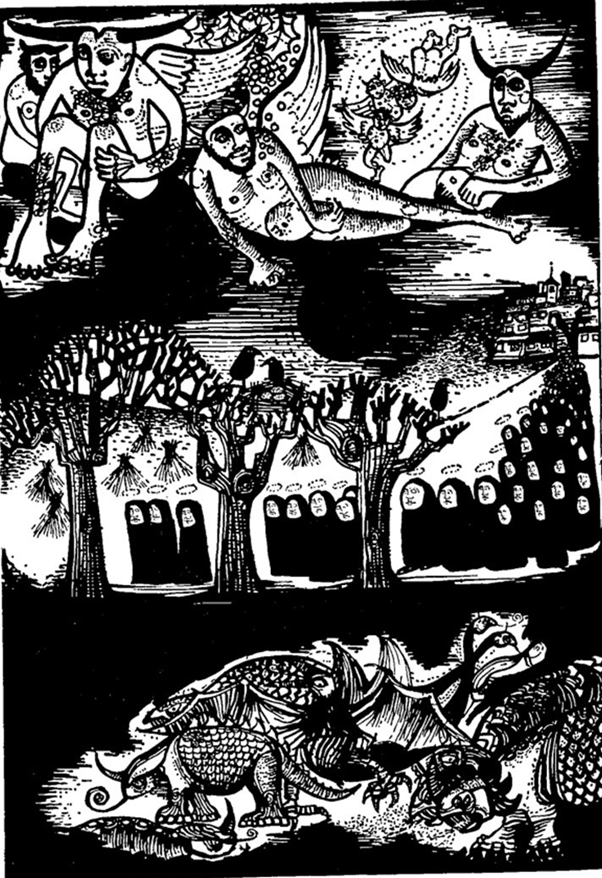

PS What I leave at the end of these inconclusive notes is an illustration (artist unknown to me) which appears facing the beginning of William Burrough’s statements from the 1962 Literary Conference in volume 11 of the Transatlantic Review. It contains images that seem almost companion to some in Fagan but yet I have no evidence for that The clerics therein seem very like those described by Jessie McRae, their obsession with a sexuality that can be idealised as narcissism (in the fallen angels above them) and degraded as reptilian, in those creatures under the clerics’ feet, just seemed appropriate. So why not share it.

What I am left with, is the strong belief that this is a ground-breaking novel.

What do you think?

Bye again, Steve xx

[1] Fagan (2021: 297).

[2] ibid:334

[3] ibid: 335

[4] ibid: 297

[5] ibid: 11

[6] ibid: 299

[7] ibid: 300

[8] ibid: 262

[9] ibid: 193

[10] Burroughs, W. (1962) cited in Reality Studio: A William Burroughs Community (2008) ‘Burroughs’ Statements at the 1962 International Writers’ Conference’ Available at: https://realitystudio.org/texts/burroughs-statements-at-the-1962-international-writers-conference/

[11] Jack, M. (2021) ‘Ones to watch in 2021: Jenni Fagan, author’ in The Scotsman Friday 1st Jan. 2021. Available at: https://www.scotsman.com/arts-and-culture/books/ones-watch-2021-jenni-fagan-author-3083375

[12] Fagan op.cit.: 195

[13] ibid: 220f.

[14] ibid: 262

[15] ‘- I like the way you kiss. / – I like your cock. / – How very delicate of you!’ This is but one example. Ibid: 191f.

[16] ibid: 191

[17] ibid: 68

[18] ibid: 68

[19]ibid: 18

[20] ibid: 193

[21] ibid: 80

[22] ibid: 44

[23] ibid: 223

[24] ibid: 334

[25] ibid: 78

Hi” i think that you should add captcha to your blog”

LikeLike